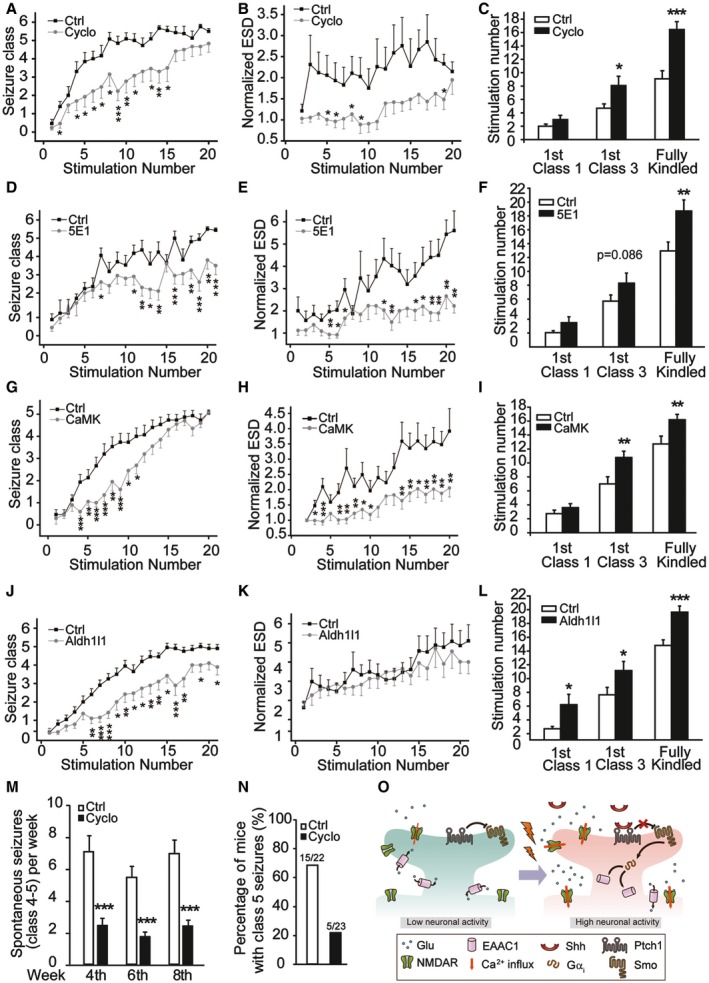

Figure 4. Inhibiting Shh pathway suppresses epileptogenesis in mouse epilepsy models.

-

A–LEffects of Cyclo (A–C, n = 14), 5E1 (D–F, n = 16–20), or ablation of Smo in CaMKIIα‐positive neurons (G–I), or ablation of Smo in Aldh1l1‐positive astrocytes (J–L) on the progression of kindling including seizure class (A, D, G, J), evoked electrographic seizure duration (ESD) (B, E, H, K), and the number of stimulations required to reach equivalent seizure intensity (C, F, I, L). In (A–F), Ctrl are vehicle‐treated mice. In (G–I), Ctrl: Smo fl/fl induced by tamoxifen; CaMK: Smo fl/fl CaMKIIα‐Cre ERT2 induced by tamoxifen, n = 14‐20. In (J–L), Ctrl: Smo +/fl; Aldh1l1: Smo +/fl Aldh1l1‐Cre, n = 19–20.

-

MFrequency of spontaneous seizures (class 4–5) in mice administrated with Cyclo or vehicle (Ctrl) at 4th, 6th, and 8th week after pilocarpine SE induction. n = 22–23.

-

NPercentage of mice with class 5 seizures within 8 weeks after pilocarpine SE induction. n = 22–23.

-

OSchematic diagram depicting a working model for Shh regulation of epileptogenesis. Epileptic activity triggers sequential responses, including Shh release, inhibition of glutamate transporter activity, and increase in extracellular glutamate, leading to epilepsy development.