Abstract

Nurses’ patient education is important for building patients’ knowledge, understanding, and preparedness for self-management. The aim of this study was to explore the conditions for nurses’ patient education work by focusing on managers’ discourses about patient education provided by nurses. In 2012, data were derived from three focus group interviews with primary care managers. Critical discourse analysis was used to analyze the transcribed interviews. The discursive practice comprised a discourse order of economic, medical, organizational, and didactic discourses. The economic discourse was the predominant one to which the organization had to adjust. The medical discourse was self-evident and unquestioned. Managers reorganized patient education routines and structures, generally due to economic constraints. Nurses’ pedagogical competence development was unclear, and practice-based experiences of patient education were considered very important, whereas theoretical pedagogical knowledge was considered less important. Managers’ support for nurses’ practical- and theoretical-based pedagogical competence development needs to be strengthened.

Keywords: discourse analysis, education professional, health care primary, teaching

Despite the provision of patient education being a key part of nursing care (Tomey, 2009), as highlighted in guidelines for nursing practices (NBHW, 2013; Redman, 2007; Van Horn & Kautz, 2010), many deficiencies are observed (Bergh, Karlsson, Persson, & Friberg, 2012). In Sweden, managers are responsible for developing nurses’ patient education by, for instance, enabling the standard, sanctioning content, and allocating time (SOSFS, 2011). There is growing interest in how nursing is managed as the context for health care is changing: The number of elderly patients with complex needs increases and technological development creates new possibilities, expectations, and challenges (World Health Report, 2008). For example, most Western countries face growing needs and costs. Attempts to improve productivity and service delivery of traditional public organizations are typically labeled “new public management” (Elzinga, 2012; Hood, 2000). This has led to health care privatizations and a trend toward having patients pass through health and social care activities as quickly as possible. “New public management” has set new priorities, such as reducing costs and promoting patient self-management. This requires a knowledgeable, skilled, and motivated health care workforce. To our knowledge, managers’ leadership in relation to the patient education provided by nurses is insufficiently studied. This study is about how first-line managers in primary care talk about primary care nurses’ patient education work.

Background

In Sweden, primary care is centered on patients’ visits to outpatient clinics and is offered by both public and private health care alternatives. According to the requirements set by the health care authority, patients have the right to choose and change health care providers. Private health care providers can, if they comply with requirements set by the health care authority (Requirements-Quality-book, 2012; SFS, 2008:962), establish a publicly financed business focused on primary care. Managers in primary care are responsible for the organization’s goals and are governed by extensive health care policy documents, entailing transformational changes for managers. Internationally and in Sweden, under the Patient Safety Act, caregivers are obliged to ensure that those working in health care have the right competences (SFS, 2010:659). New public management has introduced new concepts, for example, cost control, cost efficiency, and the patient as customer. This has created new discourses in health care, which are in need of exploration to ensure the visibility and clarity of nurses’ patient education work and managers’ leadership.

Considerable research has been devoted to the relationship between managers’ leadership styles and their consequences for the nursing workforce and work environment. Cowden, Cummings, and Profetto-McGrath (2011) highlighted the importance of transformational or relational leadership practices as they put more focus on supporting the individual nurse’s needs. A positive relation between styles of leadership, nursing workforce, and work environment was also shown in Cummings et al.’s (2010) review: for example, enhanced teamwork between physicians and nurses, enhanced nursing workgroup collaboration, nurse empowerment, as well as decreased ambiguity and conflicts in the nursing workforce. Transformational leadership practices also increased nurses’ inclination to remain at their workplaces (Cowden et al., 2011).

Nurses are important professionals for the provision of patient education and are expected to incorporate patient teaching into all aspects of their practice (Tomey, 2009; Virtanen, Leino-Kilpi, & Salantera, 2007). According to patients, specialist nurses are effective in providing information (Koutsopoulou, Papathanassoglou, Katapodi, & Patiraki, 2010). Eriksson and Nilsson (2008) found that primary care nurses were aware of the importance of practical experience, pedagogical competence, and being up-to-date to establish trusting relationships with patients to support their learning and self-management (see also Berglund, 2011; Redman, 2013). However, MacDonald, Rogers, Blakeman, and Bower (2008) found that primary care nurses were more confident in dealing with patients in the early stages of illness, particularly around the time for diagnosis, than working with them over the longer term to encourage effective self-management. Research has also shown that nurses seem to lack resources beyond personal experience and intuitive ways of working to encourage effective patient self-management. However, after attending a 2-day workshop on patient education, nurses were better prepared to provide patient education in accordance with patient-centered communication (Lamiani & Furey, 2009).

According to Bergh, Persson, Karlsson, and Friberg (2014), there exists uncertainty related to nurses’ lack of pedagogical knowledge. Nurses in primary care “never” to “occasionally,” 43% (n = 76), perceive that managers offer support in patient education work, and 60% (n = 114) have no pedagogical education (Bergh et al., 2012). The conditions and prerequisites for nurses’ patient education need to be improved (Friberg, Granum, & Bergh, 2012). Consequently, it is important to study managers’ support of nurses’ patient education work in primary care.

Aim

This study aimed to explore the conditions for nurses’ patient education work by focusing on managers’ discourses about the patient education provided by nurses in primary care.

Method

Design and Definitions

As a theoretical frame and methodological orientation, “critical discourse analysis” (CDA) was used (Fairclough, 1992, 2010). This study is part of a comprehensive investigation of the conditions for the provision of patient education by nurses (definitions, Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions.

| Concept | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Patient education | is used as a comprehensive term covering both patient teaching and information work |

| Patient teaching | is used to describe a dialogue between the nurse and the patient focusing on the patient’s learninga |

| Patient information | refers to information transfera |

| Pedagogic | refers to knowledge of teaching and achievement/accomplishment of teaching |

| Nurse | is synonymous with registered nurse |

| Manager | is synonymous with first-line manager |

| Ideological hegemony | is a set of beliefs and attitudes, where hegemony is the social struggle for power and dominance as ideological meanings are establishedb |

| Discourse | “particular way of representing certain parts or aspects of the world, which represent social groups and relations between social groups in a society in different ways”b |

| An order of discourse | “be seen as a particular combination of different discourses, which are articulated together in a distinctive way”b |

Theoretical Frame

The perspective of social constructionism (Gergen, 2009) was applied to identify and describe how managers talk about the conditions and prerequisites for nurses’ patient education work. Both what is said and what actions are taken happen in a social setting, where reality and meanings are formed in the interplay between persons, institutions, and discourses.

Fairclough’s (2010) discourse theory, focusing on language in relation to ideology, hegemony, and power, states that social practices affect discourses and vice versa (see definitions, Table 1). This means that prevailing discourses govern how persons talk about something and how they act in practice. A discourse order encompasses a discursive practice, within which there is a struggle for ideological hegemony, implying that a discursive practice can be either reproduced or replaced, thus altering the discourse order. A deeper understanding of the conditions of nurses’ patient education can be gained by clarifying the discourse order of patient education.

Participants and Procedures

In 2012, data were collected by means of focus group (FG) interviews with managers from three primary care districts in western Sweden. Information letters were sent to clinical directors, requesting managers’ participation in the study. The directors informed managers about the study and of the predetermined interview dates. Managers wishing to participate contacted the correspondent researcher. Once 12 managers had agreed to participate, 3 FGs with 4 participants each were created. The groups were considered large enough as the managers were homogeneous (all had the same position in primary care) and a narrow topic focus on conditions for nurses’ patient education was to be covered. In smaller groups, each participant gives more possibilities to talk about experiences. It is also easier for the moderator to ensure equal contribution during the interview (McLafferty, 2004; Morgan, 1996). The managers were recruited from different areas from urban to rural. Two managers announced that they would not participate on the interview day. The participating managers’ ages ranged between 41 and 68 years (median 54). Work experience as manager ranged between 0.5 and 16 years (median = 6.75) and between 9 and 31 years in a clinical work position (median = 18). Six managers had postgraduate nursing specialization in accordance with the Department of Health in Sweden at university level, while 3 had taken a leadership training course, not at university level.

The three FG interviews (FG1 = 4 managers; FG2 = 2 managers; FG3 = 4 managers) took place in conference rooms (decided by the managers), and each lasted for 1 hour. In one of the three interviews, an observer (coauthor) was present and made notes. The opening interview question was: What constitutes a nurse’s day-to-day patient education? This general question was followed by requests for explanations, especially regarding managerial support for the patient education provided by nurses. The managers’ discussions were based on aim of the study and their talk was progressed through group interaction. Following the open question, each FG discussed a wide range of topics related to patient education. The managers’ discussions were open and positive, and they contributed equally. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

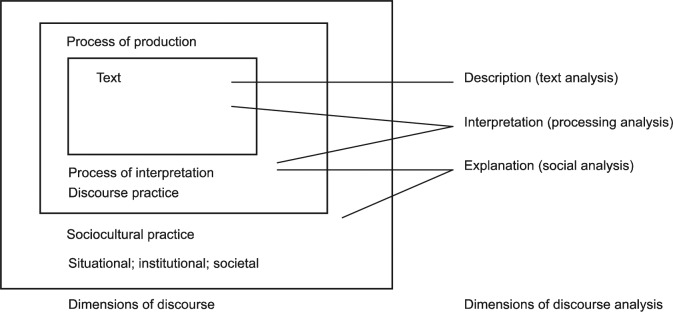

In this study, the analytical tool used was Fairclough’s (1992, 2010) CDA, a three-dimensional conception of discourse. The analysis included a description of the text, interpretation of the discursive practice, and explanation of the social practice (Figure 1). The first author conducted the analysis, which was followed up by discussing the interpretations with all authors. The analytical process started by listening to the tape and reading the transcripts multiple times. Only texts containing sequences about managers’ ways of talking about nurses’ patient education were included in the analysis. First, the text was analyzed to find specific content of what the text was about (the criterions and the properties were sought, see Table 2). The next step was to scrutinize the text itself and to analyze linguistically, which resulted in interpreted themes and subthemes that describe managers’ discursive practice. These two initial steps provided the basis for identifying the existing discourses (Table 2) and examples of the analysis (Table 3).

Figure 1.

A three-dimensional conception of discourse.

Source. Reproduced by permission (Fairclough, 2010, p. 133).

Table 2.

Criteria, Properties, and Discourses in How Managers Talk About Nurses’ Patient Education.

| Criteria | Properties | Discourses |

|---|---|---|

| Described nurses’ patient education focusing to maintain and develop the achievement of patient education | Patient education always present—a self-evidence Health promotion | Didactic |

| Described budget and costs | To have income—stay on budget | Economic |

| Described medical priorities and the utilization of professional competence | Treatment priorities and use competencies | Medical |

| Described political decision and reorganization | Routines/procedures and work methods | Organizational |

Table 3.

Managers’ Description of Nurses’ Provision of Patient Education: Example of the Data Analysis.

| Quotes | Pronoun | Metaphor | Modality | Affinity/Demarcation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| That’s the coat we have to wear every day. (FG1) | we | coat | every day (expressive) | every daya |

| I had very much use of the Motivational interviewing. Whenever I had had a patient I summarized the visit in bullet form and asked: Have you understood what I have said? I know I used this a lot for it was a great end to the visit. I ended by saying: We have agreed on this and you should get back in touch to . . . Have you also understood it this way? I thought this was extremely good. (FG3) | I I … I I . . . I I . . . I we I |

very much use (pos. appraisal) a lot you should get (obligatory) extremely good (expressive) |

Ib

Ib wec have agreed on thisc |

|

| Yeah, actually, maybe one does it many times without thinking about it, one shares experiences from, for example, telephone counseling or other settings so one probably does this in many ways, really. (FG3) | one one one |

actually, maybe probably really (hesitancy) |

actuallya, maybea

oned oned, probablya Reallya |

|

| There are countless times when patients after physician visits wonder what the physician said. Then it’s the nurses who will explain and teach. “That’s it!” (FG1) |

That’s it! |

That’s it!e |

||

| We have a strength: we discuss . . . we actually take responsibility for staff . . . but you have to take it to the next step as well, what are we going to do then. (FG2) | We . . .we you we |

have to (obligatory) |

We havef . . . wef . . . we actually take responsibilitye,f . . . you have . . . weg |

Moderating the statement expresses low/lower affinity or high/higher affinity.

Indicates that it is I/the manager who is and thinks something.

Indicates that the nurse has decided about an agreement with the patient.

Use of “one” instead of I/manager.

High affinity: All managers in the group agree, while they showed/strengthened their own responsibility and the nurses’ responsibility.

Indicates the group’s (we/the managers) responsibility.

Indicates both individual’s and the group’s responsibility.

Description of the text

The analysis of the text focused at the word level was based on the following questions: What words did managers use when describing situations and interactions in nurses’ patient education work? Did they use pronouns and employ appraising words, such as really important, very common, difficult, and desire? Did the descriptions and statements contain positively or negatively charged words such as much appreciated, and did they use metaphors?

According to Fairclough (1992), the grammatical level expresses a range of modalities. For instance, the level of power, which is how managers expressed their power in relation to the situations discussed. Interpersonal modality refers to the use of verbs (modal auxiliary verbs), for example, “must,” “should,” “would,” and “can.” Expressive modality consists of modal adverbs, for example, “perhaps,” “always,” “a little,” “ever,” “sometimes,” and “obvious.” Following Fairclough, a demarcation line (nominalization) of varying degrees between managers and superior managers and staff members is drawn. This means that the statement can be understood as reducing or strengthening managers’ responsibility for specific assignments. In addition, the presence of interdiscursivity discloses how various discourses are combined in the text.

Interpretation of the discursive practice

The discursive practice is interpreted on the basis of the linguistic analysis and the researchers’ pre-understanding. Interdiscursivity interprets the particular mix of discourses that concerns how different discourses were expressed in the text through text modalities, such as metaphors and use of personal pronouns, and how managers position themselves. For the present study, the following aspects were focused upon: Is there a creative discursive practice (for change of the dominant discourse order) or is there an established discursive practice (no tendency to change)?

Explanation of the social practice

Finally, the relationship between discursive and social practice is discussed in the light of patient education work. This relationship is explained by Fairclough’s theory of discourse focused on text in relation to ideology, hegemony, and power. The analyses of the text itself and nature of discursive practice are presented under the heading Results. To make the analysis transparent for the reader, we have included interview data and examples of theory. The consequences of discursive practice are explained as social practice within the “Discussion” section.

Ethical Considerations

The managers received written and oral information about the study’s aim, design, and voluntary nature, and confidentiality was assured before they agreed to participate. Written consent was obtained before participation. The data are kept in a locked location and are handled in accordance with the recommendations of the World Medical Association (2008). There was no need for an ethical board review as informed consent had been obtained from the participants and as there was no intention to affect the participants either physical or mental (SFS, 2003:460).

Results

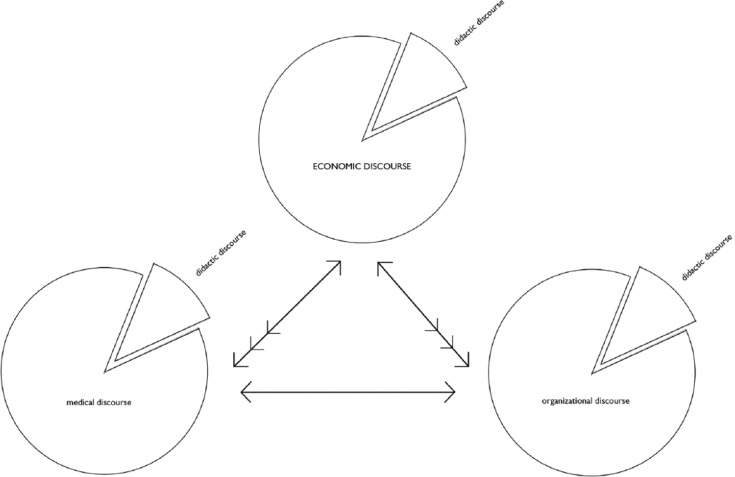

The primary care managers’ discursive practice comprised a discourse order of four discourses: economic, medical, organizational, and didactic (Figure 2). The didactic discourse served as “glue” holding the discourses together. The managers used concepts related to patient education continuously when they expressed thoughts about how to develop the work at primary care level, to strengthen public health, but the discourse was not clearly defined. The predominant economic discourse and the didactic discourse were in constant negotiation and it was important to choose working methods that contributed financially to primary care. Hence, the economic discourse made the organizational discourse adjust, and the medical discourse was obvious, for example, nurses should clarify physicians’ medical information. The text’s modality indicates that the managers had the mandate and responsibility to reorganize care in response to changing social policies.

Figure 2.

Prevailing discourse order affecting patient education.

Didactic Discourse

Managers expressed that patient education permeated all primary care work and that patient education working methods were often discussed, especially when it came to group teaching and different patient schools: “It’s part of the work you should do and I see it as part of our job description” (FG2). The managers used the metaphor “the coat,” and the expressive modality, “We have to wear every day” (FG1, Table 3), reflect that patient education was always present. The use of the personal pronoun “we” referred to the managers themselves as a group, and the interpersonal modalities “you should” referred to the nurses. The managers had the power to express this obligation. The use of “I” described managers’ responsibility to include patient education in work descriptions.

Maintaining and developing pedagogic competence

The managers highlighted research showing that health care workers have low skills in the art of teaching. Research findings were discussed based on the pros and cons of different patient education methods and the development of patient education skills was dominated by collegial and interdisciplinary exchange of knowledge. Forums for patient education discussions were typically feedback conversations with the manager and different gatherings: “nurses’ weekly meetings . . . physicians and nurses meet once a month . . . at ordinary ward meetings we share both positive and negative experiences of patient education” (FG2). Nurses attending specialist nursing education sometimes shared exam projects, which were perceived as very rewarding, but Bachelor nurse students’ projects were not seen as an integral part of competence development. Patient education was above all developed through internal courses, such as motivational interviewing: “Nurses stay at a conference hotel for a couple of days and ‘live with patient education.’ This arrangement was much appreciated” (FG2). A manager, who had previously worked as a nurse, stated,

I had very much use of the Motivational interviewing. Whenever I had had a patient I summarized the visit in bullet form and asked: Have you understood what I have said? I know I used this a lot for it was a great end to the visit. I ended by saying: We have agreed on this and you should get back in touch to . . . Have you also understood it this way? I thought this was extremely good. (FG3, Table 3)

The manager used positive appraisal words when stressing the usefulness of developing pedagogical knowledge through motivational interviewing. In the excerpt, the patient was invited to respond to yes/no questions, which indicates the nurse’s power to decide the content of the discussion. For instance, the patient was not asked to express their understanding in their own words. Hence, when the manager talked about acting as a nurse, the pronoun “I” was used to describe that the nurse has responsibility for how patient education was done. Qualifications in pedagogy at university level were considered to be of less importance:

I do not think all of my nurses really have to take a course and acquire 7.5 ECTS [European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System] in pedagogy. I observe and listen as they meet their patients, and I think they are pedagogically very knowledgeable. (FG1)

Having extensive practical experience was important: “You must have a wide range of practical experiences; otherwise you can’t work at primary care . . . nor understand what the actual problem is . . . ask the right questions to get relevant answers” (FG2). When the managers described their and the nurses’ discussions about patient education, they expressed: “Yeah, actually, maybe one does it many times without thinking about it, one shares experiences from, for example, telephone counseling or other settings so one probably does this in many ways, really” (FG3, Table 3). The managers moderated their statements (demarcation, used “one” instead of “I”) when talking about patient education, thus distancing themselves from responsibility and expressing uncertainty about patient education. Patient education was somewhat invisible. When asked to further describe the time spent by nurses on keeping up with the pedagogical field, for example, by reading and discussing articles, it was obvious that nurses rarely requested pedagogical courses and primary care nurses themselves should take responsibility for patient education development, as in the following interview excerpt:

The work place is really tough, tough for one to get the economics to work . . . about time for patient education development, it’s hard to know . . . Nurses have no specific hours per week for this, absolutely not. Nah, it’s very irregular so I really cannot answer that. (FG3)

Health promotion—Part of daily work

The result showed that it was important and obvious for nurses to adopt a clear and holistic view on patient care. Managers described several situations that from a pedagogical point of view were difficult to manage in health promotion work. For instance, when meeting nonnative Swedish-speaking patients, uncertainty arose about whether or not the patients understood the patient education, even when an interpreter was present.

Furthermore, communication with elderly patients can be problematic as they can feel uncomfortable about asking questions, and it can be difficult to find the appropriate teaching levels. Based on their own practical experience, managers suggested how nurses can provide patient education to elderly persons by comparing it with working with children: “I think all patients should be addressed as if one’s talking to a child: a very pedagogical way” (FG1). It was important to ensure that patients understood by repeating and individualizing the patient education. The main message was to ensure patients’ knowledge and understanding, but the managers expressed uncertainty about how to handle this.

According to managers, patient education was primary care’s social mission: to improve people’s health by knowledge, understanding, and support of healthy self-care. A way to improve patients’ self-care management was to create a nursing-responsible-nurse and a medical-responsible-physician. These changes also benefited patient education for anxious patients calling or coming to the clinic almost daily and wanting a professional visit. These patients needed human contact rather than medical treatment. The metaphor “super market business” was used by managers to describe this: “Patients calling about everything because they know we are open . . . they should be able to shop everything from us” (FG1).

Another initiative for improving people’s health, mentioned by the managers, was the “Senior-Health” project: an initiative to reach out to seniors by offering conversations on health and lifestyle and a contact phone number. According to managers, having a nursing-responsible-nurse/medical-responsible-physician has improved continuity and security, and facilitated patients’ knowledge and understanding about self-care management.

When talking about patient education, the managers spontaneously discriminated between the concepts “patient teaching” and “patient information.” They used concepts such as starting from the patient’s view, dialogue, informal or real knowledge, formal pedagogical competence, pedagogical work, and pedagogy as a tool. However, there was no clarity in how these concepts were used or how patient education was defined, but, “There are good conditions for developing nurses’ patient education: . . . it’s just that we not always call it teaching, but if one sees it as a whole it’s actually there” (FG1).

Economic Discourse

The introduction of “Health-Choice” can be seen as a step toward health care’s adaptation to market economy conditions. Patients can choose between health settings, and various primary care settings compete for patients. Patients differ with regard to their value in terms of profit and loss. In hospitals, patients are discharged too rapidly and thus social responsibility and costs are transferred to primary care. Higher costs also come from the significant increase in the number of elderly and young patients. Young, anxious patients consulting primary care, without a real need of medical treatment, is a new social phenomenon. To reduce processing times and costs, some patients were referred to the nursing-responsible-nurse and medical-responsible-physician. Managers used economic and business terms when talking about patients: “Your personal health care provider as your personal banker, and thus does not stop the acute queue [patients telephoning/coming to primary care in need of an urgent meeting]. We have many such patients” (FG1). Another cause of increased costs was that patients’ expectations on primary care did not fit within its mission and current economic frames. Furthermore, patients visited primary care directly after discharge from hospitals to gain knowledge about their health. In this context, managers stressed that the responsibility of a professional patient education should be based on the patients’ needs at the various health care settings to avoid unnecessary costs for society, as described in the following interview excerpt:

In hospitals they might not take full responsibility and teach all parts to patients, but hand it over to the next health care setting . . . primary care . . . you should not transfer the patient to another health care setting without first teaching the patient how to solve the problem . . . it [the discharge from the hospital] goes too quickly, at the expense of knowledge. It often happens that patients do not get written information and that the patient receives a verbal message [about health] while the patient is being informed of discharge and then the patient’s mind is on other things, “if there is milk in the fridge.” (FG2)

Considering that patient education represents substantial financial interests for health care operations, it is important that nurses’ tick off patient education on an activity list. Indeed, the payment practices may have the effect of stimulating nurses to create more patient education as it generates more income:

It has the motivating effect of lighting a little fire under your butt, for example, when patients come to physicians’ appointments and physical activity was prescribed, nurses have motivational interviewing, for example, on smoking and alcohol habits. (FG1)

Medical Discourse

The importance of medical priority and better use of the medical competence were highlighted. Changes such as Health-Choice and drop-in from Mondays to Fridays have changed the culture and reduced the priorities of appropriate medical competence, especially for patients with chronic disease:

Medical priorities have kind of become lost . . . Competences are not used appropriately . . . drop-in, availability and all this nagging of multi-seekers requires nurses to do tasks such as register patients, which anyone can do. (FG1)

After medical consultations, nurses explained and clarified physicians’ information: “There are countless times when patients after physician visits wonder what the physician said. Then it’s the nurses who will explain and teach. That’s it!” (FG1, Table 3). Managers stressed the nurses’ responsibility for following up the patients’ understanding and knowledge of the medical information. Especially the modality “That’s it” indicated that managers rely on the patient education provided by nurses. This strong modal expression both reflects and promotes nurses’ behavior, responsibility, and power over patient education in relation to physicians’ information and patients’ needs for knowledge provided by nurses.

Organizational Discourse

According to Swedish law, patients have the right to choose and change health care providers whenever they like, “The Health-Choice” (SFS, 2008:962). Health care must, as far as possible, be designed and implemented in agreement with the patient, that is, promote patient integrity, autonomy, and also empower them through information, consent, and participation (SFS, 2010:659, 2014:821) The managers are responsible for the organization meeting the goals of health care (Requirements-Quality-book, 2012; SOSFS, 2011). In this study, political decisions were determining factors, and managers expressed their own responsibility and power for making the required changes.

Reorganization

The Health-Choice reform allowed patients to approach any primary care center, as “drop-ins,” irrespective of their place of residence. This market adjustment has led to higher patient flows in primary care and made health care: “an availability rather than a competency issue” (FG2). This means that the key issue is that patients meet professionals, although not necessarily professionals with the appropriate competence. According to managers, patients often misunderstand their treatment, making it crucial they meet the appropriate professionals.

To highlight the importance of using the available professionals’ competence when meeting patients, managers have started to reorganize and introduce nursing-responsible-nurses and medical-responsible-physicians, entailing changed routines. Furthermore, to help nurses focus on patients’ understanding and better structure their patient education work would require “to stop the patient roaming around in the health care system” (FG1), meaning that patients go to various health care facilities asking the same questions. To reduce this behavior, standardized triage and responses to fundamental questions should be created for primary care, hospitals, and pharmacies: “Get the same answer no matter who they meet” (FG2).

Managers stressed that nurses were very independent and that an efficient way to support them is to take advantage of their ideas for organizational change. Managers should plan for continuous discussions on, for instance, how to allocate time for and decide content of patient education individually and in regular group meetings, but stressed, “It’s not about not having time . . . you have to take necessary time” (FG1) for patients. Nurses had a clear personal responsibility for how their work is organized to ensure enough time for the patients, and managers had the power to express this obligation (interpersonal modality). The time and space allocated for nurses’ own pedagogical competence development in the organization was unclear and rarely discussed.

“We have strength: We discuss . . . we actually take responsibility for staff . . . but you have to take it to the next step as well, what are we going to do then” (FG2). The importance of learning from each other by collaboration and transparency was apparent, but sometimes they discussed a patient education problem, and no change was made even if a need was apparent. Two managers described that they spent part of their working time as nurses, which was helpful for understanding the nursing work and how nurses can be supported in their patient education work. It was highlighted that nurses learn about patient education when managers have “practical supportive ways of working that create good situations for patient education” (FG2).

Discussion

The managers constructed different discourses through how they talked. All these discourses were important for and affected nurses’ patient education and differed in terms of how much power they expressed.

The importance of cost efficiency based on economic and medical considerations—that is, the economic and medical discourses—appeared to be obvious in the context of this study. These discourses could be seen as discourses that were uncritically accepted as given and normal. The didactic discourse was dependent on the other discourses, even if the pedagogical concepts permeated all work in primary care. The concepts were used more in a “common sense” or “self-evident” way, which contributed to the dependent status of the didactic discourse.

Conflicts occurred when societal demands, such as Health-Choice, affected both the budget and the way patient education routines were built. The economic discourse thus influenced and ruled the organization as indicated in the organizational discourse. In today’s society, the need for health care promotion and prevention is increasing. This creates more opportunities and income for clinics, while possibly increasing the demands on nurses’ patient education and pedagogical competence. By means of the various discourses, we can determine what is important and how to understand phenomena and the expressed norms. The discourses spring from different ideological beliefs about how things should be and thus construct the world around us (Fairclough, 2010). The didactic discourse was present in managers’ construction of patient education. However, the content of the didactic discourse was neither clear nor obvious. One could say that it was part of an official sociopolitical health discourse, which according to various steering documents must be part of primary care work. The didactic discourse was first and foremost present in nurses’ practical experiences, where knowledge means possession of power, which is evident in the master–apprentice relationship (nurse–patient). Workplaces had no distinct pedagogical competence descriptions for nurses in general, which makes it difficult to update the necessary patient education competence to meet requirements (Berglund, 2011; SOSFS, 2011). The work in primary care demanded solid practical experience and managers related the nurses’ patient education to their own experience as nurses and to practical tasks. They believed that many nurses were skilled pedagogues without any need of further education or pedagogical training. However, it is easy to fall into routine procedures (Eriksson & Nilsson, 2008), as patient education is a normal feature in nurses’ daily work. Opportunities to disseminate research results and exam projects among nurses were limited although they represent an opportunity for competence development, in collaboration between educational institutions and workplaces for the purpose of creating work-based learning (Williams, 2010).

An aging population with more people suffering chronic diseases and disability, more anxious patients making repeated visits, and patients placing higher demands make patient education in primary care complex. The simultaneous new public management influences increase the demand for nurses’ patient education while they also need “to do more” with the same resources, as the goal of supporting patients’ learning is central in developing self-care management. In this study, managers changed the routines and developed patient education in the organization by listening to nurses’ ideas for improvements, which is in line with Drenkard’s (2012) recommended framework for leadership in relation to organization.

A change in nurses’ patient education can be achieved when managers truly use nurses’ ideas and support the process of change, thus achieving creative discursive practice that changes the social practice (Fairclough, 2010). This is in line with Bourdieu’s (1995) claim that professionals are best equipped to develop strategies to preserve routines or to change them. Therefore, nurses also need support to update their pedagogical competence to make a difference (Berglund, 2011; Redman, 2013).

The economic discourse ruled through political decisions and the power of new public management has influenced primary care’s health care. Managers identified changed routines, that is, drop-in, as threats to patient education that may result in the removal of the pedagogical “coat.” In addition, patients “roaming around” in the organization because of neglected patient education may entail suboptimal use of available resources and be uneconomic for all parties: patients, different health care facilities, and society in general. The interviews showed that health care professionals were not fully aware of the power they exercised over care seekers or of their insufficient pedagogical training.

The care-seeking person is constructed as a patient in the encounter with a health care organization. The meeting, dialogue, support, and the patients’ view on the care needs and how responsibility is attributed are vital starting points in individualizing patient education and supporting patient self-care management (Audulv, Asplund, & Norbergh, 2010; Friberg, Pilhammar Andersson, & Bengtsson, 2007). The patient’s role was not clear in the managers’ statements, although they were generally seen as demanding customers. Maybe nurses are constructing the patient by means of patient education. We suggest appointing a specialist nurse with formal pedagogic education at master level who can follow current research in patient education at the workplace and work with other health care settings to reduce ambiguities for both professionals and patients. Hopefully, a “Public Health” discourse focusing on patient education will be created in the near future.

According to the managers, they provided professional and powerful leadership by supporting and ensuring nurses’ competences, which supports Drenkard’s (2012) claim in this respect. By asking whether nurses needed pedagogical training, they saw themselves as promoting patient education, as nurses themselves seldom asked for such training. We highlight the importance of critically reflecting on patient education practice and managers’ support for continuous training in patient education. To counteract the negative effect of routine work, we believe that all nurses should have formal pedagogical education. Moreover, in “a changing world” specific patient education strategies need to be developed to handle the challenges of, for example, web-based health care resources (Ali, Krevers, Sjöström, & Skärsäter, 2014).

By highlighting the medical discourse, managers expressed that nurses often explained and clarified physicians’ information to patients after medical consultations. This can be seen as an example of interdisciplinary collaboration. It is important to clarify the content of patient education, and who is responsible for it, as this is an important feature for improving quality (Cummings et al., 2010) and developing patient education work. If patients are well educated, they are less inclined to, out of ignorance about their condition, seek care the day after being discharged from hospital care. Collaboration between physicians and nurses, based on the individual patient’s knowledge needs, should result in patient education strategies developed as a structured and reflective part of teamwork.

Methodological Issues

Studies have showed that the conditions for nurses’ patient education need to be further improved (Friberg et al., 2012), and a social construction approach can help to focus on what changes need to be done. FG interviews are particularly useful through direct access to the language and concepts that structure the participants’ experiences. The main advantage of FG interviews is the purposeful use of interaction to generate data (Morgan, 1996). In this study, the managers themselves have signed up for the interviews, and it should pave the way for rich data. Individual interviews may have given greater depth in data. In FG2, there were two informants, as two persons announced, at the interview day, that they could not participate and it was too late to rearrange dates. This interview was very informative as the interaction between the managers highlighted issues of relevance to the conditions for nurses’ patient education.

Managers constructed beliefs and thoughts by interaction in a certain context and time, and such results are not to be seen as correct descriptions of conditions for patient education provided by nurses. The use of Fairclough’s (2010) CDA made it possible to connect the managers’ use of language, ideology, and power to grasp data with focus on managers’ discursive practice concerning the patient education provided by nurses. Rigor is taken into consideration as the participating managers, the topic, and the analytical process are described, and data are linked to their sources. The primary care managers in this study were all from the same region in Sweden. Managers in other regions might have constructed other discourses. Moreover, more FG interviews might have given more variations and strengthened the result.

All authors were experienced nurses with formal pedagogical education, which can be both a weakness and strength. Furthermore, all interviews were conducted by one author, with a coauthor present as an observer at one occasion, and the data gathering and analysis were critically evaluated throughout the process by all authors.

Conclusion

The managers expressed power and shouldered their responsibility to reorganize patient education routines within the hegemonic economic discourse. The didactic discourse was somewhat unclear, and nurses’ autodidactic ability was highlighted. This study shows that patient education is not organized and structured in a way that allows it to be viewed as a separate competence area for nurses. The opinion that practical-based patient education knowledge learned at the workplace is the most important form of knowledge has to be combined with reflected and theory-based pedagogical knowledge. To meet societal primary health care requirements, with focus on structured support for patient self-care management, the content of the prevailing discourses must be challenged. Nurses need support to pursue a more thoughtful patient education with both practical- and theoretical-based pedagogical skills with focus on promoting a health discourse.

Practical Implications

Knowledge about how managers relate nurses’ patient education work to different discourses should be used as a reflective tool in critical discussions at the workplace to clarify and visualize the conditions for nurses’ daily patient education work. Managers’ opinions should form the basis for political discussions on different levels about how society should promote awareness of theory-based pedagogical knowledge among managers and nurses, and thereby support nurses’ pedagogical development. Knowledge about how managers talk about patient education should be used to explore and develop cooperation between different health care settings to create structured support for patients’ self-care management and to foster a health discourse.

Acknowledgments

We thank the managers who participated and openly shared their thoughts and experiences, as well as Jenny Gunnarsson Payne, associate professor in European ethnology, and Kate Galvin, professor of nursing practice, for their advice and support.

Author Biographies

Anne-Louise Bergh, MSc, RN, doctoral student, is a lecturer in caring science at Academy of Care, Working Life and Social Welfare, University of Borås, Sweden.

Febe Friberg, PhD, RN, is a professor in nursing sciences at the University of Stavanger, Norway.

Eva Persson, PhD, RN, is an associate professor in nursing at the Department of Health Sciences, University of Lund, Sweden.

Elisabeth Dahlborg-Lyckhage, PhD, RN, is an associate professor in caring science at the Department of Nursing, Health and Culture, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ali L., Krevers B., Sjöström N., Skärsäter I. (2014). Effectiveness of web-based versus folder support interventions for young informal carers of persons with mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education & Counseling, 94, 362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audulv Å., Asplund K., Norbergh K.-G. (2010). Who’s in charge? The role of responsibility attribution in self-management among people with chronic illness. Patient Education & Counseling, 81, 94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergh A.-L., Karlsson J., Persson E., Friberg F. (2012). Registered nurses’ perceptions of conditions for patient education—Focusing on organizational, environmental and professional cooperation aspects. Journal of Nursing Management, 20, 758–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01460.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergh A.-L., Persson E., Karlsson J., Friberg F. (2014). Registered nurses’ perceptions of conditions for patient education—Focusing on aspects of competence. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28, 523–536. doi: 10.1111/scs.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund M. (2011). Taking charge of one’s life—Challenges for learning in long-term illness (Doctoral thesis). Växjö Linnaeus University, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. (1995). The logic of practice. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cowden T., Cummings G., Profetto-McGrath J. (2011). Leadership practices and staff nurses’ intent to stay: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Management, 19, 461–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01209.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings G. G., MacGregor T., Davey M., Lee H., Wong C. A., Lo E., . . . Stafford E. (2010). Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 363–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenkard K. (2012). The transformative power of personal and organizational leadership. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 36, 147–154. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e31824a0538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga A. (2012). Features of the current science policy regime: Viewed in historical perspective. Science and Public Policy, 39, 416–428. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scs046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson I., Nilsson K. (2008). Preconditions needed for establishing a trusting relationship during health counselling—An interview study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 2352–2359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of Language. London, England: Longman Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Friberg F., Granum V., Bergh A.-L. (2012). Nurses’ patient-education work: Conditional factors—An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management, 20, 170–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg F., Pilhammar Andersson E., Bengtsson J. (2007). Pedagogical encounters between nurses and patients in a medical ward—A field study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44, 534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen K. J. (2009). An invitation to social construction. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hood C. (2000). Paradoxes of public-sector managerialism, old public management and public service bargains. International Public Management, 3, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7494(00)00032-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsopoulou S., Papathanassoglou E. D., Katapodi M. C., Patiraki E. I. (2010). A critical review of the evidence for nurses as information providers to cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 749–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamiani G., Furey A. (2009). Teaching nurses how to teach: An evaluation of a workshop on patient education. Patient Education & Counseling, 75, 270–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald W., Rogers A., Blakeman T., Bower P. (2008). Practice nurses and the facilitation of self-management in primary care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04585.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty I. (2004). Focus group interviews as a data collecting strategy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. L. (1996). Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 129–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NBHW. (2013). National Board of Health and Welfare. National guidelines for methods of preventing disease—Summary. Retrieved from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/nationalguidelines/nationalguidelinesformethodsofpreventingdisease

- Redman B. K. (2007). The practice of patient education—A Case Study approach (10th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri 63146: Mosby Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Redman B. K. (2013). Advanced practice nursing ethics in chronic disease self-management. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Requirements-Quality-book. (2012). [Krav - och Kvalitetsbok]. Retrieved from http://www.vgregion.se/upload/Regionkanslierna/VG%20Prim%c3%a4rv%c3%a5rd/KoK/Krav%20och%20kvalitetsbok%202013.pdf

- SFS. (2003:460). Swedish Code of Statutes, number 460. Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor [Act on ethical review of research involving humans. Revised 2008]. Retrieved from http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/Dokument-Lagar/Lagar/Svenskforfattningssamling/Lag-2003460-om-etikprovning_sfs-2003-460/

- SFS. (2008:962). Swedish Code of Statutes, number 962. Vårdval i primärvården enligt bestämmelserna i lagen om valfrihetssystem (LOV) [The introduction of choice of care in primary care]. Retrieved from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2012/2012-2-9

- SFS. (2010:659). Swedish Code of Statutes, number 659. Patientsäkerhetslag (chapter 6, § 6). [Patient Safety Act]. Retrieved from https://lagen.nu/ 2010:659 [Google Scholar]

- SFS. (2014:821). Swedish Code of Statutes, number 821. Patientlag (chapters 3-5) [Patient’s Act]. Retrieved from http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/Dokument-Lagar/Lagar/Svenskforfattningssamling/sfs_sfs-2014-821/

- SOSFS. (2011). National Board of Statutes. Ledningssystem för systematiskt kvalitetsarbete. Handbok för tillämpning av föreskrifter och allmänna råd (SOSFS 2011:9) om ledningssystem för systematiskt kvalitetsarbete [Managerial system for systematic quality work. Directions and general advice]. National Board of Health and Welfare; Retrieved from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2012/2012-6-532011-9 [Google Scholar]

- Tomey A. M. (2009). Nursing leadership and management effects work environments. Journal of Nursing Management, 17, 15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn E. R., Kautz D. (2010). NNN language and evidence-based practice guidelines for acute cardiac care. Dimension Critical Care Nurse, 29, 69–72. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181c92fea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen H., Leino-Kilpi H., Salantera S. (2007). Empowering discourse in patient education. Patient Education & Counseling, 66, 140-146. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. (2010). Understanding the essential elements of work-based learning and its relevance to everyday clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 624–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Report. (2008). The primary health care—Now more than ever. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/index.html

- World Medical Association. (2008). World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html