Abstract

Epileptic seizures are crucial clinical manifestations of recurrent neuronal discharges in the brain. An imbalance between the excitatory and inhibitory neuronal discharges causes brain damage and cell loss. Herbal medicines offer alternative treatment options for epilepsy because of their low cost and few side effects. We established a rat epilepsy model by injecting kainic acid (KA, 12 mg/kg, i.p.) and subsequently investigated the effect of Uncaria rhynchophylla (UR) and its underlying mechanisms. Electroencephalogram and epileptic behaviors revealed that the KA injection induced epileptic seizures. Following KA injection, S100B levels increased in the hippocampus. This phenomenon was attenuated by the oral administration of UR and valproic acid (VA, 250 mg/kg). Both drugs significantly reversed receptor potentiation for advanced glycation end product proteins. Rats with KA-induced epilepsy exhibited no increase in the expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor 3, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and chemokine receptor type 2, which play a role in inflammation. Our results provide novel and detailed mechanisms, explaining the role of UR in KA-induced epileptic seizures in hippocampal CA1 neurons.

1. Introduction

Seizures are often diagnosed as a neurological disease, with a prevalence of approximately 1%. They are always accompanied by inflammation and oxidative stress [1–4]. Kainic acid (KA) is a potent neuroexcitatory amino acid to activate kainate receptor in the brain and is typically used for developing an animal epilepsy model [5–7]. The KA-induced epileptic seizure model is widely used to exhibit symptoms similar to those of seizures in the human temporal lobe [8–10]. An imbalance of excitatory glutamate and inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, induces uncontrolled electric discharges in the central nervous system (CNS), thus leading to epilepsy [11, 12]. Studies on antiepileptic drugs, namely, topiramate [13] and gabapentin [14], have reported a reduction in the excitatory neurotransmitter level and an increase in GABA biosynthesis, respectively. More than 30% of clinical patients with epilepsy cannot be treated adequately with traditional antiepileptic drugs because of the resultant side effects [15]. Our previous study indicated that auricular electroacupuncture can attenuate epilepsy by altering the TRPA1, pPKCα, pPKCε, and pERk1/2 signaling pathways in KA-induced epilepsy in rats [16].

The S100 proteins are calcium-regulated low-molecular weight proteins and were first reported in the brain [17]. The S100 protein family consists of 24 members only expressed in vertebrates and with cell-specific expression patterns [17]. The S100B subtype is the most abundant in the CNS, melanocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [17–19]. S100B has been well documented for its role in enhancing neurite outgrowth [20, 21]. The potentiation of S100B expression is typically involved in chronic epilepsy [22]. A previous study reported that oral Uncaria rhynchophylla (UR) reduced KA-induced epileptic seizures and neuronal death and also lowered S100B proteins levels in rats [23].

The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), a transmembrane receptor, is upregulated in temporal lobe epilepsy and contributes to experimental seizures [24]. RAGE activation initiates downstream cellular responses such as inflammation and cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation [24]. RAGE has been found to be involved in inflammatory processes [25–27] and is increased in neurons and glia after brain injury [28–31]. The inflammatory activation of damage-associated molecules, including S100 proteins, can further activate RAGE, resulting in acute and chronic diseases [32]. RAGE regulates NF-κB and ERK signaling resulting from tissue inflammation [33].

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are subdivided into three groups of G-protein coupled receptors: Group I mGluRs are mainly located at postsynaptic neuron whereas groups II (mGluR3) and III mGluRs are predominantly expressed at presynaptic sites to regulate release of neurotransmitters [34]. Recent evidences suggest that mGluR3 plays a crucial role in regulating glutamatergic transmission at both presynaptic and postsynaptic sites in the hippocampus [35].

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) is a mediator of inflammation released by activated monocytes and fibroblasts. In addition, MCP-1 is activated through lipopolysaccharide or cytokine stimulation [36, 37]. Gong et al. (1997) indicated that MCP-1 is significantly involved in inflammation, particularly in arthritic inflammation. Haringman et al. (2006) reported that MCP-1 is crucial in leukocyte migration and inflammatory disorders [38, 39]. MCP-1 has frequently been reported to play a role in inflammatory diseases. Wu et al. (2012) reported that MCP-1 plays a crucial role in the migration of neural progenitor cells during neuroinflammation [40]. Furthermore, MCP-1 can promote mesenchymal stem cell migration in vitro and can be blocked by an antagonist [41].

The chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR-2) is a G-protein coupled receptor that is majorly involved with and expressed in inflammatory cells, such as monocytes, neutrophils, basophils, and T-lymphocytes, and in CNS neurons [42–44]. CCR-2 can be activated by inflammatory factors, including chemokines and interleukins [40, 45]. Sandblad et al. (2015) reported on 20 chemokine receptors on 3 monocyte subsets and suggested that CCR-2 is highly expressed in classical (CD14+ CD16−) but not in nonclassical (CD14+ CD16+) monocytes [46].

UR has been suggested to exert an anticonvulsant effect in KA-induced epileptic seizures in rats [23, 47]. The constituents of UR, namely, rhynchophylline, isorhynchophylline, and isocorynoxeine, exert neuroprotective effects by reducing glutamate-mediated neuronal loss in cerebellar granule cells [48]. Furthermore, UR reduces apoptosis and exerts a neuroprotective effect [47] by inhibiting c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity in KA-induced epileptic seizures in rats [49].

To determine the detailed mechanisms of UR in KA-induced epileptic seizures, we investigated whether UR alters S100B, RAGE, mGluR3, MCP-1, and CCR-2 protein levels 6 weeks after KA injection. We demonstrated that oral UR attenuated the overexpression of S100B proteins, in a similar manner to the positive control by VA. Moreover, we indicated that the RAGE receptor, a possible downstream target of S100B, is increased in rats after KA injection and further reduced by UR administration, which is indicative of its therapeutic effect. Similar results were not observed with mGluR3, MCP-1, and CCR-2 proteins. In the current study, oral UR was found to reduce availability of S100B to the RAGE pathway in epileptic seizures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (200–300 g) were used in this study. All rats had free access to food and water. Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of China Medical University and followed the Guide for the Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy Press).

2.2. Extraction of Uncaria rhynchophylla

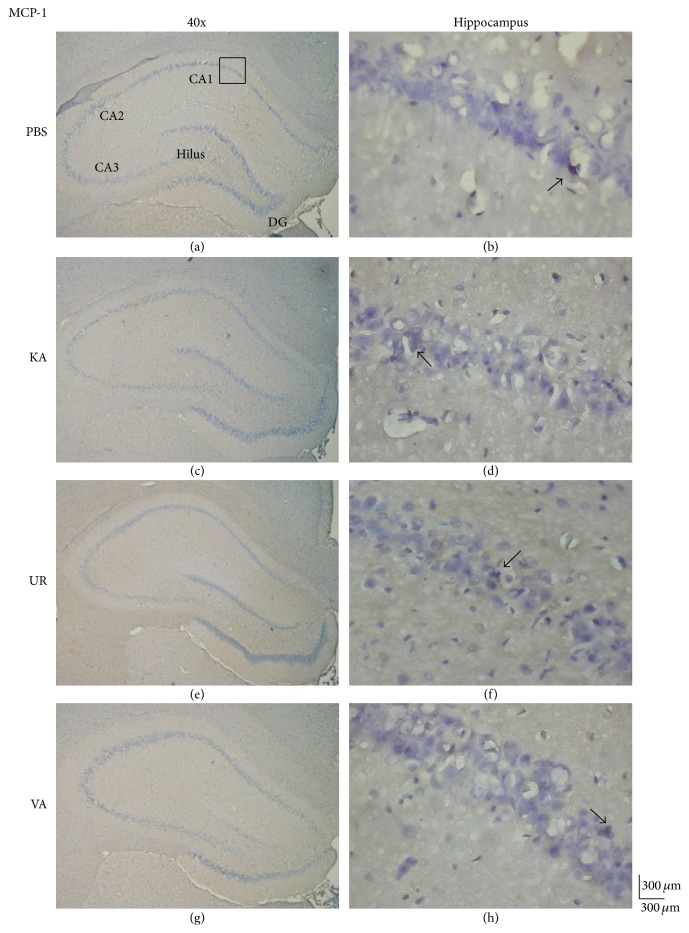

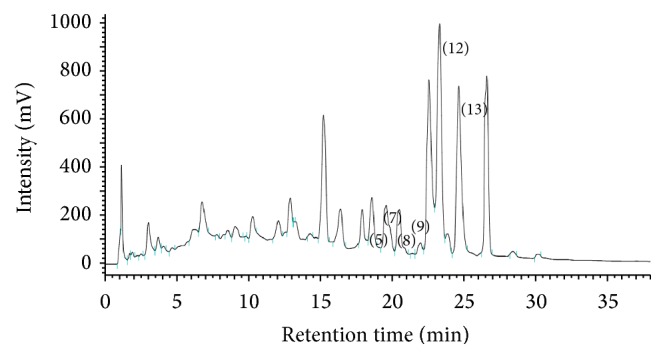

UR (Rubiaceae, Uncaria rhynchophylla [Miq.] Jacks.) was purchased from China and authenticated and extracted by Koda Pharmaceutical Company (Taoyuan, Taiwan), a reputable pharmaceutical manufacturing factory located in Taiwan. Extraction of UR was performed as described in previous studies [49, 50]. In brief, 8 kg of crude UR was extracted with 64 kg of 70% alcohol by boiling for 35 min. These extracts were filtered, freeze-dried, and subsequently stored in a dryer box to obtain a total yield of 566.63 g (7.08%). The freeze-dried extracts were stored at 4°C. The freeze-dried UR extracts were tested for quality with a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (interface D-700, Pump L-7100, UV-Vis Detector L-7420; Hitachi Instruments Service Co. Ltd., Ibaraki-ken, Japan) by using rhynchophylline (Matsuura Yakugyo Co. Ltd., Japan) as the standard, which was obtained from Koda Pharmaceutical Company. The HPLC fingerprint of UR was analyzed by Koda Pharmaceutical Company as described in our previous study [48] and was shown in Figure 1. Each gram of freeze-dried extract contained 1.81 mg of the pure alkaloid component of UR. The dose response for this compound was reported in our previous study [51]. Hence, this effective dose was used for all of the experiments in the current study.

Figure 1.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fingerprint of Uncaria rhynchophylla. The peaks at Rt 17.5 to 25.5 min can be assigned to isocorynoxeine (5), rhynchophylline (7), corynoxeine (8), isorhynchophylline (9), hirsuteine (12), and hirsutine (13).

2.3. Establishment of the Epileptic Seizure Model

Twenty-four SD rats (n = 6 for all groups) were used in this study. Four days prior to electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyogram (EMG) recordings, all rats underwent stereotactic surgery following anesthesia with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.). The scalp was incised from the midline, and the skull was exposed. Stainless-steel screw electrodes were implanted on the dura mater over the bilateral sensorimotor cortices to serve as recording electrodes. A reference electrode was placed in the frontal sinus. Bipolar electrical wires were placed on the neck muscles for EMG recordings. Electrodes were connected to an EEG and EMG-monitoring machine (MP100WSW, BIOPAC System, Inc., CA, USA). The epileptic seizures were confirmed with observations of behavioral changes, including wet-dog shakes, paw tremors, and facial myoclonia, under a freely moving and conscious state and epileptiform discharges on EEG recordings. Rats with more than 250 wet-dog shakes and those with the number of facial myoclonia plus paw tremors ≥100 were selected. The rats were randomly divided into 4 experimental groups, as follows: (1) the control group containing rats that received only phosphate buffered saline (PBS) i.p. without KA; (2) the KA group containing rats that received KA (12 mg/kg, i.p.) only; (3) the UR group containing rats that received oral UR (1 g/kg, 5 d/wk) continuously for 6 weeks, starting the day after KA injection; and (4) the VA group containing rats that received oral VA (250 mg/kg/d, 5 d/wk) continuously for 6 weeks, starting the day after KA injection. All rats were sacrificed on day 42 after KA injection, and the brains were removed and divided into left and right brains. Left brain was for immunohistochemistry staining and right brain was for western blot analysis.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry Staining

Animals were heavily anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused with normal saline through the cardiac vascular system, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Merck, Frankfurt, Germany) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). The brains were removed and postfixed in the same fixative overnight at 4°C. After brief washing with PBS, the brains were transferred to a 30% sucrose solution in 0.01 M PBS for cryoprotection, and coronal sections containing the hippocampal area were cut into 20 μm thick slices through cryosectioning. The sections were preincubated for 2 h at 25°C with 10% horse serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS to avoid nonspecific binding. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody CCR2 (1 : 1000, Abcam, UK), mGluR3 (1 : 1000, Abcam, UK), MCP-1 (1 : 1000, Abcam, UK), RAGE (1 : 1000, Abcam, UK), S100B (1 : 1000, Novus Biologicals, USA), Actin (1 : 1000, Millipore, USA), 0.1% horse serum, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The sections were subsequently incubated for 2 h at 25°C with biotinylated-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted at 1 : 200; Vector, Burlingame, CA 94010, USA), followed by incubation with avidin-horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC-Elite, Vector). The sections were finally visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. Sections were washed 3 times with PBS during the incubation steps for 10 min per cycle. The stained hippocampal slices were sealed under the coverslips and then examined for the presence of immune-positive hippocampal neurons using a microscope (Olympus, BX-51, Japan). The immune-positive signals were quantified with NIH ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Right hippocampi were excised immediately for protein extraction. Total protein was prepared by homogenizing the hippocampi in a lysis buffer containing 20 mmol/L of imidazole-HCl (pH 6.8), 100 mmol/L of KCl, 2 mmol/L of MgCl2, 20 mmol/L of EGTA (pH 7.0), 300 mmol/L of sucrose, 1 mmol/L of NaF, 1 mmol/L of sodium vanadate, 1 mmol/L of sodium molybdate, 0.2% Triton X-100, and a proteinase inhibitor cocktail for 1 h at 4°C. From each sample, 30 μg of proteins were extracted and analyzed through a BCA protein assay. They were subjected to 7.5%–10% SDS-Tris glycine gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in a TBST buffer (10 mmol/L of Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L of NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20), incubated with the primary antibody in TBST with bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 500) was used as the secondary antibody. The membrane was developed using the ECL-Plus protein detection kit. Where applicable, the image intensities of specific bands were quantified with NIH ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance between the PBS, control, UR, and VA groups was analyzed through one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Induction of Epileptic Seizures after KA Injection Using EEG

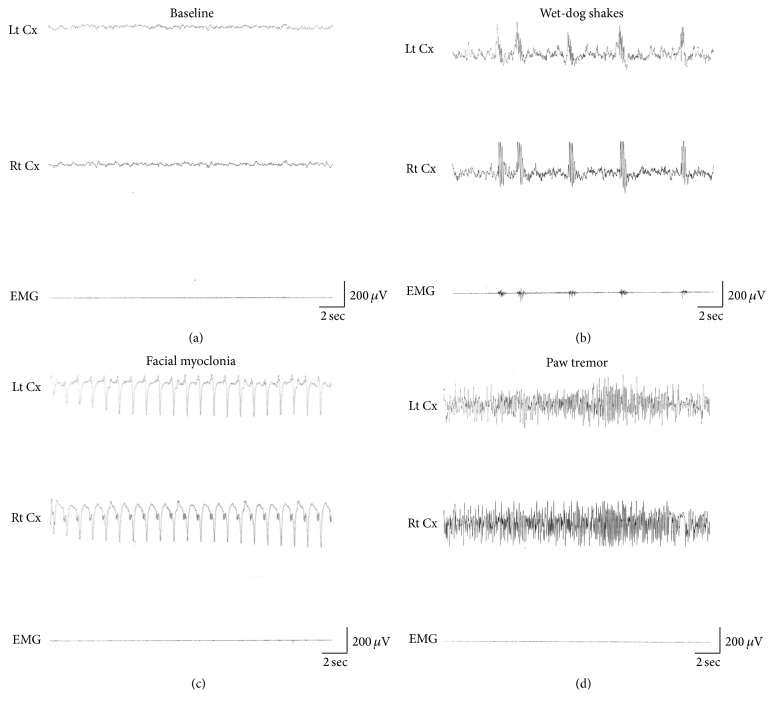

An epileptic seizure is a crucial sign of clinical epilepsy resulting from electric discharges in the brain. In the current study, we injected KA (12 mg/kg, i.p.) to establish an in vivo epileptic rat model. Twenty-four SD rats were injected with KA for inducing epileptic seizures. Three major symptoms of seizures were observed, and their own characteristic electrophysiological activities were recorded. Limbic motor signs such as wet-dog shakes, paw tremor, and facial myoclonia were recorded as the symptoms of epilepsy. Figure 2(a) shows the baseline conditions. Wet-dog shakes were defined as a polyspike-like EEG activity (Figure 2(b)). Facial myoclonia was defined as a characteristic continuous sharp EEG activity (Figure 2(c)). Paw tremors were characterized by a continuous-spike EEG activity (Figure 2(d)). These parameters were used as an adequate induction of epileptic seizures, and these rats were used for investigating the effect of UR on epilepsy in all of the experiments. The number of wet-dog shakes, facial myoclonia, and paw tremors were significantly different from controls but not between each other. (all P < 0.05, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Alteration of electroencephalographic (EEG) signals in KA-injected rats. Baseline EEG activity in the sensorimotor cortex was characterized by 6–8 Hz activity in rats when awake (a). KA-induced temporal lobe seizures, including wet-dog shakes (WDS) with intermittent polyspike-like activity (b), facial myoclonia with continuous sharp waves (c), and paw tremor (PT) with continuous-spike activity (d). Each type of seizures had its own characteristic EEG activity. Lt Cx: EEG recording of the left sensorimotor cortex; Rt Cx: EEG recording of the right sensorimotor cortex; EMG: EMG recording of the neck muscles.

Table 1.

Kainic acid-induced epileptic seizures.

| PBS | KA | UR | VA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-dog shakes | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 309.0 ± 55.1∗ | 317.3 ± 47.8∗ | 312.8 ± 31.1∗ |

| Facial myoclonia | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 90.3 ± 12.9∗ | 97.8 ± 12.4∗ | 93.8 ± 9.4∗ |

| Paw tremor | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 38.3 ± 4.46∗ | 32.8 ± 6.5∗ | 38.3 ± 12.0∗ |

Mean ± standard deviation. Kainic acid-induced epileptic seizure includes wet-dog shakes, facial myoclonia, and paw tremors. PBS: PBS group; KA: KA group; UR: UR group; VA: VA group; ∗P < 0.05 compared with the PBS group.

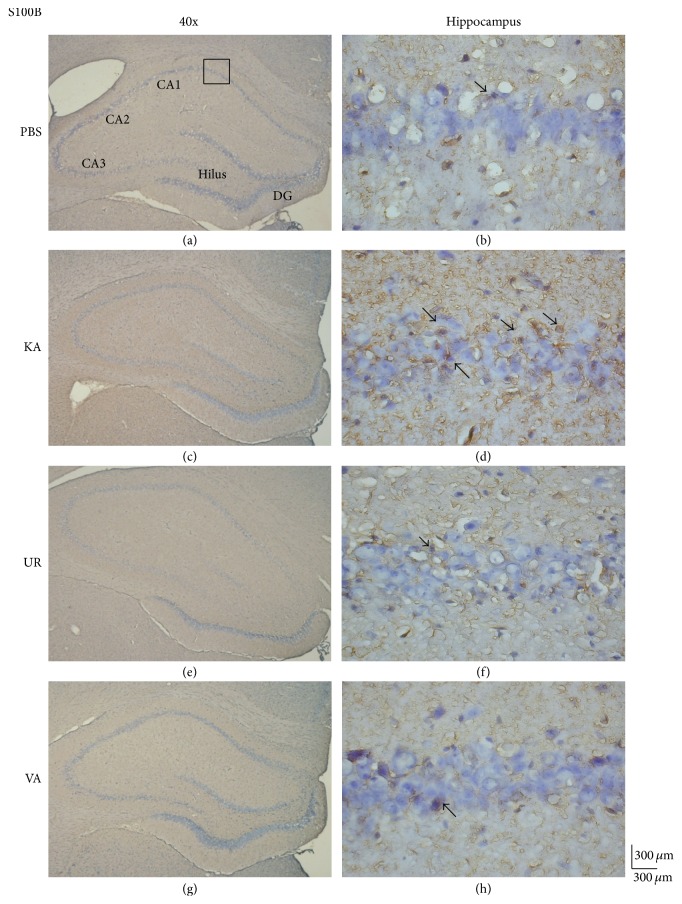

3.2. Oral UR Reduces S100B Enhancement in KA-Induced Epilepsy

We previously reported that oral UR reduces the number of epileptic seizures and neuronal death [23]. In the current study, we attempted to determine whether a 6-week long-term administration of UR reduces S100B expression. S100B proteins were detected in the hippocampus of rats that received PBS injection (Figure 3(a), 97.0 ± 14.39 cells/field, n = 6). Specifically, KA injection increased the expression of S100B proteins significantly in the hippocampal CA1 area (Figure 3(b), 260.67 ± 34.89 cells/field, n = 6, P < 0.05, compared with the PBS group). These elevated levels were further attenuated following UR administration (Figure 3(c), 129.17 ± 19.38 cells/field, n = 6, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group). Similar observations were reported after the oral administration of VA, a positive control for epilepsy treatment (Figure 3(d), 112.33 ± 20.92 cells/field, n = 6, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry staining of S100B and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining in hippocampal sections from the PBS, KA, UR, and VA-pretreated groups. HE (blue) and S100B (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (a) and CA1 (b) in the PBS group. HE (blue) and S100B (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (c) and CA1 (d) areas in the KA group. HE (blue) and S100B (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (e) and CA1 (f) areas in the UR group. HE (blue) and S100B (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (g) and CA1 (h) areas in the VA group. The left panel was imaged at 40x magnification, and the right panel was imaged at 400x magnification.

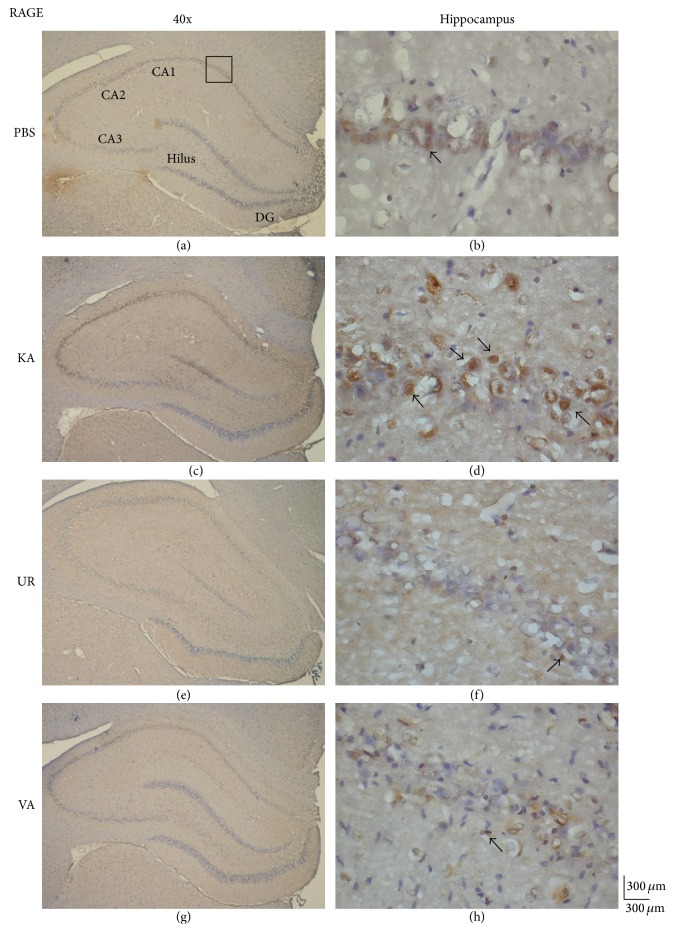

We next analyzed whether oral UR alleviates the overexpression of RAGE in hippocampal neurons after KA injection. We determined that PBS injection did not induce RAGE potentiation (Figure 4(a), 143.17 ± 38.11 cells/field, n = 6). After KA injection, the levels of RAGE proteins in the hippocampus increased substantially (Figure 4(b), 247.67 ± 84.1 cells/field, n = 6, P < 0.05, compared with the PBS group). These phenomena were attenuated following the administration of UR (Figure 4(c), 100.5 ± 27.59 cells/field, n = 6, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group) and VA (Figure 4(d), 102.5 ± 32.25 cells/field, n = 6, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group), suggesting that RAGE plays a critical role in controlling epileptic seizures.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry staining of RAGE and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining in hippocampal sections from the PBS, KA, UR, and VA-pretreated groups. HE (blue) and RAGE (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (a) and CA1 (b) in the PBS group. HE (blue) and RAGE (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (c) and CA1 (d) areas in the KA group. HE (blue) and RAGE (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (e) and CA1 (f) areas in the UR group. HE (blue) and RAGE (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (g) and CA1 (h) areas in the VA group. The left panel was imaged at 40x magnification, and the right panel was imaged at 400x magnification.

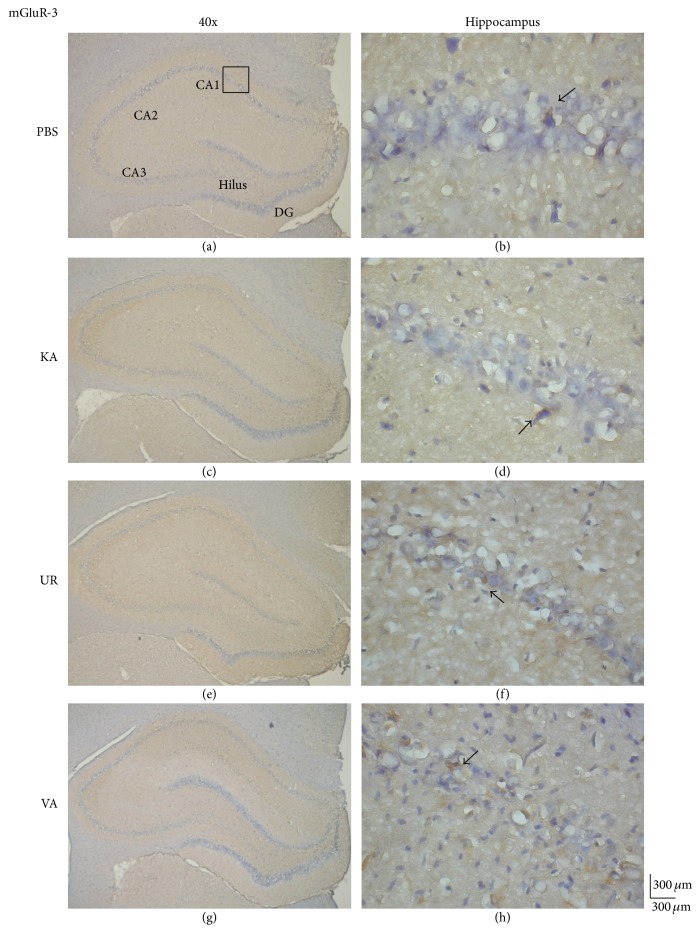

We investigated whether mGluR3, an excitatory receptor that is highly associated with S100B activation, was involved in KA-induced epileptic seizures. Our results revealed that the levels of mGluR3 proteins were similar in the hippocampus following the injection of both PBS (Figure 5(a), 91.83 ± 11.79 cells/field, n = 6) and KA (Figure 5(b), 97.17 ± 36.64 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the PBS group), indicating a negative role in this process. Similar results were obtained for the UR (Figure 5(c), 84.17 ± 10.11 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the KA group) and VA groups (Figure 5(d), 87.17 ± 22.53 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the KA group). These data suggested that the expression of mGluR3 proteins was not influenced by KA injection alone or KA injection followed by UR or VA treatment.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry staining of mGluR3 and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining in hippocampal sections from the PBS, KA, UR, and VA-pretreated groups. HE (blue) and mGluR3 (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (a) and CA1 (b) in the PBS group. HE (blue) and mGluR3 (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (c) and CA1 (d) areas in the KA group. HE (blue) and mGluR3 (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (e) and CA1 (f) areas in the UR group. HE (blue) and mGluR3 (brown) immunostaining in the whole hippocampus (g) and CA1 (h) areas in the VA group. The left panel was imaged at 40x magnification, and the right panel was imaged at 400x magnification.

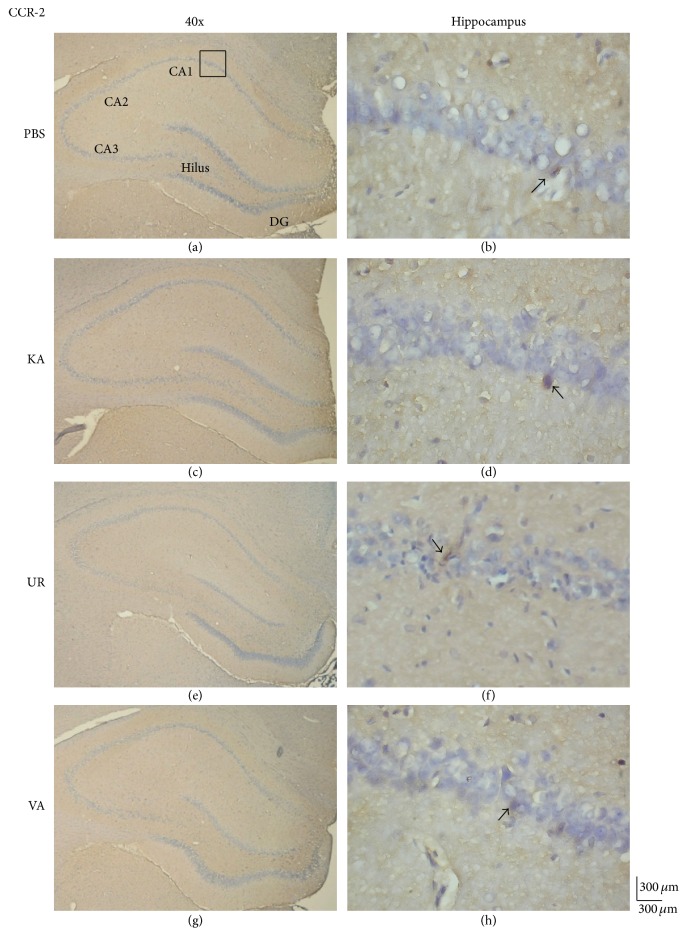

We investigated whether the level of MCP-1, an inflammation-related molecule, was altered in KA-induced epileptic seizures. The results revealed the presence of MCP-1 proteins in the hippocampus (Figure 6(a), 34.83 ± 17.87 cells/field, n = 6) and unaltered levels of MCP-1 proteins 6 weeks following KA injection (Figure 6(b), 42.83 ± 33.63 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the PBS group). Furthermore, the 6-week administration of oral UR did not alter MCP-1 expression (Figure 6(c), 47.5 ± 20.95 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the KA group). The administration of VA did not exert any effects on the levels of MCP-1 proteins in the hippocampus (Figure 6(d), 41.47 ± 19.47 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the KA group). We further investigated whether CCR-2, a chemokine receptor for MCP-1 that is reportedly involved in acute and chronic inflammation, participated in KA-induced epileptic seizures. CCR-2 levels were detected in the hippocampus (Figure 7(a), 56.83 ± 9.6 cells/field, n = 6) and were unaltered in the KA group 6 weeks after KA injection (Figure 7(b), 54.5 ± 6.89 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the PBS group). Oral UR did not affect CCR-2 expression (Figure 7(c), 54.17 ± 14.41 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the KA group). Oral VA also did not affect CCR-2 expression in the rat hippocampus (Figure 7(d), 50.0 ± 2.53 cells/field, n = 6, P > 0.05, compared with the KA group).

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry staining of MCP-1 and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining in hippocampal sections from the PBS, KA, UR, and VA-pretreated groups. HE (blue) and MCP-1 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (a) and CA1 (b) in the PBS group. HE (blue) and MCP-1 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (c) and CA1 (d) areas in the KA group. HE (blue) and MCP-1 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (e) and CA1 (f) areas in the UR group. HE (blue) and MCP-1 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (g) and CA1 (h) areas in the VA group. The left panel was imaged at 40x magnification, and the right panel was imaged at 400x magnification.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemistry staining of CCR-2 and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining in hippocampal slices from PBS, KA, UR, and VA-pretreated groups. HE (blue) and CCR-2 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (a) and CA1 (b) in PBS group. HE (blue) and CCR-2 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (c) and CA1 (d) areas in KA group. HE (blue) and CCR-2 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (e) and CA1 (f) areas in UR group. HE (blue) and CCR-2 (brown) immunostaining in whole hippocampus (g) and CA1 (h) areas in VA group. The left panel was imaged at 40x magnification while the right panel was at 400x magnification.

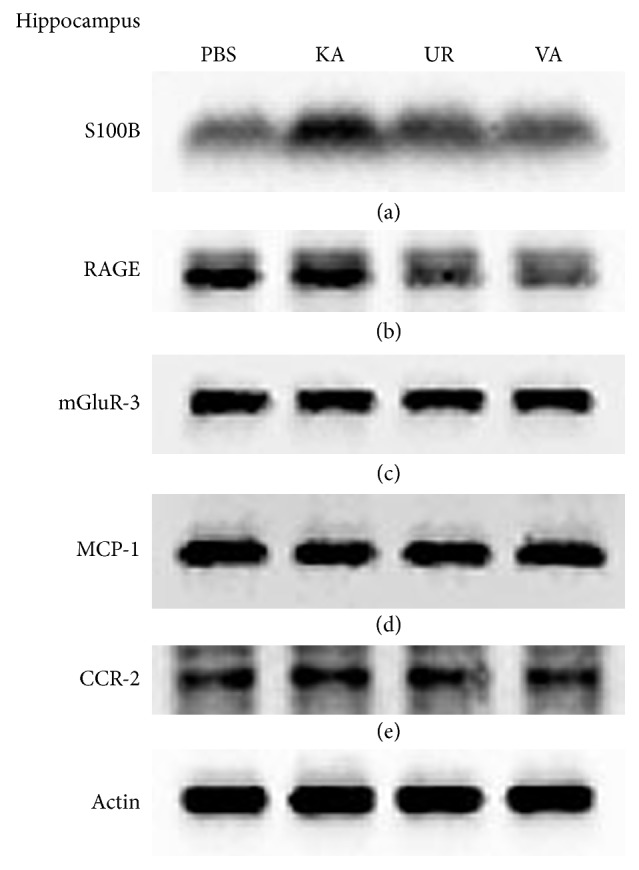

3.3. KA Injection Increases Expression of S-100B and RAGE and Is Attenuated by Oral UR and VA

In our previous study, we demonstrated that oral UR attenuates the overexpression of S100B and RAGE in the rat hippocampus. We further examined this pattern by performing western blotting for quantifying protein levels. Our results revealed that S100B increased in rats following KA injection (Figure 8, 1.44 ± 0.06 versus 1.07 ± 0.10 density, n = 3, compared with the PBS group) and can be reversed with the oral administration of UR (Figure 8, 1.25 ± 0.08 density, n = 3, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group) and VA (Figure 8, 1.10 ± 0.09 density, n = 3, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group). In a similar manner, RAGE levels increased in the band density in the KA group (Figure 8, 0.81 ± 0.1 versus 0.70 ± 0.06 density, n = 3, compared with the PBS group) but returned to baseline after the administration of UR (Figure 8, 0.59 ± 0.05 density, n = 3, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group) and VA (Figure 8, 0.54 ± 0.08 density, n = 3, P < 0.05, compared with the KA group). Similar results in the levels of mGluR3, MCP-1, and CCR-2 proteins (Figure 8) were not observed. These data presented strong evidence that oral UR alleviated overexpression in the S100B and RAGE signaling pathway, rather than of mGluR3, MCP-1, and CCR-2 proteins.

Figure 8.

Western blot analysis of S100B, RAGE, mGluR3, MCP-1, and CCR-2 in the hippocampus from the PBS, KA, UR, and VA-pretreated groups. (a) S100B; (b) RAGE; (c) mGluR3; (d) MCP-1; (e) CCR-2. β-Actin was set as an internal control.

4. Discussion

In this study, we established a rat epileptic seizure model via i.p. injection of KA and monitored the symptoms by EEG. Three major phenotypes of seizures, namely, wet-dog shakes, paw tremors, and facial myoclonia, were recorded. We used these rats to determine the therapeutic effects and detailed mechanisms of oral UR. We hypothesized that S100B and target receptor RAGE increased after KA injection and were further alleviated by oral administration of UR as well as VA, the positive control. This phenomenon was not observed with the expression of excitatory mGluR3 receptor proteins, suggesting that it did not play a role in KA-initiated epileptic seizures. Furthermore, the administration of UR and VA did not reduce MCP-1 overexpression and the associated downregulation of CCR-2 significantly. This novel finding indicated a crucial effect of UR and underlying mechanisms.

UR is a Chinese medicinal plant with sedative and anticonvulsive effects in epilepsy. An alkaloidal extract of UR contains 5 constituents, namely, rhynchophylline, isorhynchophylline, corynoxeine, hirsutine, and hirsuteine. Rhynchophylline is an oxindole moiety that protects rat neuronal cells from the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced neurotoxicity [48]. The number of NMDA-mediated neuronal deaths and the expression of apoptosis-relevant genes in the hippocampal sections increased [52]. The administration of the alkaloid fraction of UR in cultured hippocampal neurons alleviates neuronal death and apoptosis-associated genes including c-jun, bax, and p53 [53, 54]. We suggested in our previous studies that UR lowers KA-induced lipid peroxide levels [51] and offers neuroprotection against KA-induced epilepsy by regulating GFAP and S100B [23]. Other studies have reported that brain trauma induces temporal lobe damage and causes temporal lobe epilepsy, hippocampal sclerosis, and neocortical damage [55, 56]. We also reported in our previous studies that oral UR prevents death of hippocampal neurons and downregulates the overexpression of glial cells. Moreover, we suggested that S100B protein is potentiated after KA injection, and this phenomenon can be attenuated by oral UR 2 weeks after KA injection. In the current study, we observed that 6-week treatment with oral UR reduced S100B overexpression, suggesting its long-term therapeutic effect. In addition, we demonstrated that the expression of the related target receptor for S100B, RAGE, increased following KA injection and was further attenuated by oral UR and VA. Moreover, mGluR3, an excitatory glutamate receptor, did not participate in this process. Sakatani et al. reported that application of the mGluR3 agonist resulted in a significant increase of extracellular S100B [57]. We suggest that functional activation of mGluR3 is crucial for increasing extracellular S100B instead of protein change.

We previously suggested that oral UR might prevent hippocampal neuronal death from KA treatment by reducing glial cell proliferation. Manley et al. indicated that brain injury-induced epileptic seizures initiate an inflammatory response by potentiating MCP-1 expression and related microglia potentiation during seizure injury within 18 h [58]. Their finding revealed that cytokines play a crucial role in neuroinflammation-related epilepsy [58]. These findings are consistent with our previous findings indicating that auricular electroacupuncture reduces inflammation-related epileptic seizures by altering the TRPA1, pPKCα, pPKCε, and pERk1/2 signaling pathways in KA-induced rats [16]. Another study noted an increase in the level of MCP-1 proteins in the hippocampus [59]. Moreover, Lv et al. (2014) indicated that the activation of the NF-κB pathway might contribute to MCP-1 upregulation and microglial activation under epilepsy conditions 24 h after treatment [60]. These results indicated a crucial role of MCP-1 in epileptic seizures. In the current study, the therapeutic period was prolonged up to 6 weeks, mimicking a clinical observation of chronic epilepsy. Our results demonstrated that oral UR treatment for 6 weeks significantly reduced S100B and RAGE overexpression significantly but not that of mGluR3, MCP-1, and CCR-2.

5. Conclusion

We established a KA-induced epileptic rat model with KA injections for target research. Our results indicated that KA injection increased the expression of S100B and RAGE in the rat hippocampus. In addition, we reported that oral UR reduced S100B and RAGE overexpression. Similar results were observed after the oral administration of VA, which was used as a positive control. Furthermore, we demonstrated that mGluR3, MCP1, and CCR-2 levels were not altered in all groups, suggesting a negative role in KA-induced epilepsy. Overall, the results implied clear and novel mechanisms for UR treatment on KA-induced epileptic seizures.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan (Grant no. MOST 103-2320-B-039-010), and also was supported by a grant from Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University (Ministry of Education, The Aim for the Top University Plan), and in part by the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW105-TDU-B-212-133019).

Competing Interests

The authors wish to confirm that there is no known conflict of interests associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

References

- 1.Xu D., Miller S. D., Koh S. Immune mechanisms in epileptogenesis. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2013;7, article no. 195 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao R.-R., Xu X.-C., Xu F., et al. Metformin protects against seizures, learning and memory impairments and oxidative damage induced by pentylenetetrazole-induced kindling in mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2014;448(4):414–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folbergrová J. Oxidative stress in immature brain following experimentally-induced seizures. Physiological Research. 2013;62(1):S39–S48. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tombini M., Squitti R., Cacciapaglia F., et al. Inflammation and iron metabolism in adult patients with epilepsy: does a link exist? Epilepsy Research. 2013;107(3):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao L.-R., Dudek F. E. Repetitive perforant-path stimulation induces epileptiform bursts in minislices of dentate gyrus from rats with kainate-induced epilepsy. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105(2):522–527. doi: 10.1152/jn.00456.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudek F. E., Pouliot W. A., Rossi C. A., Staley K. J. The effect of the cannabinoid-receptor antagonist, SR141716, on the early stage of kainate-induced epileptogenesis in the adult rat. Epilepsia. 2010;51(3):126–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim Y. B., Ryu J. K., Lee H. J., et al. Midkine, heparin-binding growth factor, blocks kainic acid-induced seizure and neuronal cell death in mouse hippocampus. BMC Neuroscience. 2010;11(1, article 42) doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonucci F., Bozzi Y., Caleo M. Intrahippocampal infusion of botulinum neurotoxin e (BoNT/E) reduces spontaneous recurrent seizures in a mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50(4):963–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao M. S., Hattiangady B., Reddy D. S., Shetty A. K. Hippocampal neurodegeneration, spontaneous seizures, and mossy fiber sprouting in the F344 rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;83(6):1088–1105. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raedt R., Van Dycke A., Van Melkebeke D., et al. Seizures in the intrahippocampal kainic acid epilepsy model: characterization using long-term video-EEG monitoring in the rat. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2009;119(5):293–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczurowska E., Mareš P. NMDA and AMPA receptors: development and status epilepticus. Physiological Research. 2013;62(1):S21–S38. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo J., Liu J., Fu W., et al. The effect of electroacupuncture on spontaneous recurrent seizure and expression of GAD67 mRNA in dentate gyrus in a rat model of epilepsy. Brain Research. 2008;1188(1):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gryder D. S., Rogawski M. A. Selective antagonism of GluR5 kainate-receptor-mediated synaptic currents by topiramate in rat basolateral amygdala neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(18):7069–7074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07069.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan R. B., Hunt D. L., Thompson S. J. Gabapentin to control seizures in children undergoing cancer treatment. Journal of Child Neurology. 2004;19(2):97–101. doi: 10.1177/08830738040190020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutula T. P., Dudek F. E. Unmasking recurrent excitation generated by mossy fiber sprouting in the epileptic dentate gyrus: an emergent property of a complex system. Progress in Brain Research. 2007;163:541–563. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y.-W., Hsieh C.-L. Auricular electroacupuncture reduced inflammation-related epilepsy accompanied by altered TRPA1, pPKCα, pPKCε, and pERk1/2 signaling pathways in kainic acid-treated rats. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:9. doi: 10.1155/2014/493480.493480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donato R., Cannon B. R., Sorci G., et al. Functions of S100 proteins. Current Molecular Medicine. 2013;13(1):24–57. doi: 10.2174/156652413804486214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rickmann M., Wolff J. R. S100 protein expression in subpopulations of neurons of rat brain. Neuroscience. 1995;67(4):977–991. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00615-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichikawa H., Jacobowitz D. M., Sugimoto T. S100 protein-immunoreactive primary sensory neurons in the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia of the rat. Brain Research. 1997;748(1-2):253–257. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)01364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shashoua V. E., Hesse G. W., Moore B. W. Proteins of the brain extracellular fluid: evidence for release of S‐100 protein. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1984;42(6):1536–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winningham-Major F., Staecker J. L., Barger S. W., Coats S., Van Eldik L. J. Neurite extension and neuronal survival activities of recombinant S100 beta proteins that differ in the content and position of cysteine residues. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109(6):3063–3071. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin W. S. T., Yeralan O., Sheng J. G., et al. Overexpression of the neurotrophic cytokine S100β in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;65(1):228–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Y.-W., Hsieh C.-L. Oral Uncaria rhynchophylla (UR) reduces kainic acid-induced epileptic seizures and neuronal death accompanied by attenuating glial cell proliferation and S100B proteins in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;135(2):313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iori V., Maroso M., Rizzi M., et al. Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts is upregulated in temporal lobe epilepsy and contributes to experimental seizures. Neurobiology of Disease. 2013;58:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bianchi M. E., Manfredi A. A. High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein at the crossroads between innate and adaptive immunity. Immunological Reviews. 2007;220(1):35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt A. M., Yan S. D., Yan S. F., Stern D. M. The biology of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligands. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular Cell Research. 2000;1498(2-3):99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern D., Du Yan S., Fang Yan S., Marie Schmidt A. Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts: a multiligand receptor magnifying cell stress in diverse pathologic settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54(12):1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao T.-L., Yuan X.-T., Yang D., et al. Expression of HMGB1 and RAGE in rat and human brains after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2012;72(3):643–649. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823c54a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lue L.-F., Yan S. D., Stern D. M., Walker D. G. Preventing activation of receptor for advanced glycation endproducts in Alzheimer's disease. Current Drug Targets: CNS and Neurological Disorders. 2005;4(3):249–266. doi: 10.2174/1568007054038210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma L., Nicholson L. F. B. Expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in Huntington's disease caudate nucleus. Brain Research. 2004;1018(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasaki N., Toki S., Chowei H., et al. Immunohistochemical distribution of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in neurons and astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Research. 2001;888(2):256–262. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianchi M. E. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2007;81(1):1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu J., Nishimura M., Wang Y., et al. Early release of HMGB-1 from neurons after the onset of brain ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2008;28(5):927–938. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrido Sanabria E. R., Wozniak K. M., Slusher B. S., Keller A. GCP II (NAALADase) inhibition suppresses mossy fiber-CA3 synaptic neurotransmission by a presynaptic mechanism. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;91(1):182–193. doi: 10.1152/jn.00465.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maciejak P., Szyndler J., Turzyńska D., et al. The effects of group III mGluR ligands on pentylenetetrazol-induced kindling of seizures and hippocampal amino acids concentration. Brain Research. 2009;1282:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rollins B. J. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1: a potential regulator of monocyte recruitment in inflammatory disease. Molecular Medicine Today. 1996;2(5):198–204. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liou L.-B., Tsai W.-P., Chang C. J., Chao W.-J., Chen M.-H. Blood monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and adapted disease activity Score28-MCP-1: favorable indicators for rheumatoid arthritis activity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055346.e55346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong J.-H., Ratkay L. G., Waterfield J. D., Clark-Lewis I. An antagonist of monocyte chamoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) inhibits arthritis in the MRL-lpr mouse model. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;186(1):131–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haringman J. J., Gerlag D. M., Smeets T. J. M., et al. A randomized controlled trial with an anti-CCL2 (anti-monocyte chemotactic protein 1) monoclonal antibody in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(8):2387–2392. doi: 10.1002/art.21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Y., Chen Q., Peng H., et al. Directed migration of human neural progenitor cells to interleukin-1β is promoted by chemokines stromal cell-derived factor-1 and monocyte chemotactic factor-1 in mouse brains. Translational Neurodegeneration. 2012;1, article 15 doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo J., Zhang H., Xiao J., et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 promotes the myocardial homing of mesenchymal stem cells in dilated cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(4):8164–8178. doi: 10.3390/ijms14048164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baggiolini M., Dewald B., Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines—CXC and CC chemokines. Advances in Immunology. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chuntharapai A., Lee J., Hébert C. A., Kim K. J. Monoclonal antibodies detect different distribution patterns of IL-8 receptor A and IL-8 receptor B on human peripheral blood leukocytes. The Journal of Immunology. 1994;153(12):5682–5688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murdoch C., Monk P. N., Finn A. CXC chemokine receptor expression on human endothelial cells. Cytokine. 1999;11(9):704–712. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahtga S. K., Murphy P. M. The CXC chemokines growth-regulated oncogene (GRO) α, GROβ, GROγ, neutrophil-activating peptide-2, and epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating peptide-78 are potent agonists for the type B, but Not the type A, human interleukin-8 receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(34):20545–20550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandblad K. G., Jones P., Kostalla M. J., Linton L., Glise H., Winqvist O. Chemokine receptor expression on monocytes from healthy individuals. Clinical Immunology. 2015;161(2):348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang N.-Y., Liu C.-H., Su S.-Y., et al. Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq) Jack plays a role in neuronal protection in kainic acid-treated rats. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2010;38(2):251–263. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X10007828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimada Y., Goto H., Itoh T., et al. Evaluation of the protective effects of alkaloids isolated from the hooks and stems of Uncaria sinensis on glutamate-induced neuronal death in cultured cerebellar granule cells from rats. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1999;51(6):715–722. doi: 10.1211/0022357991772853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsieh C.-L., Ho T.-Y., Su S.-Y., Lo W.-Y., Liu C.-H., Tang N.-Y. Uncaria rhynchophylla and rhynchophylline inhibit c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation and nuclear factor-κB activity in kainic acid-treated rats. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2009;37(2):351–360. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X09006898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho T.-Y., Tang N.-Y., Hsiang C.-Y., Hsieh C.-L. Uncaria rhynchophylla and rhynchophylline improved kainic acid-induced epileptic seizures via IL-1β and brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(6):893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh C.-L., Chen M.-F., Li T.-C., et al. Anticonvulsant effect of uncaria rhynchophylla (miq) Jack, in rats with kainic acid-induced epileptic seizure. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 1999;27(2):257–264. doi: 10.1142/s0192415x9900029x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes P. E., Alexi T., Yoshida T., Schreiber S. S., Knusel B. Excitotoxic lesion of rat brain with quinolinic acid induces expression of p53 messenger RNA and protein and p53-inducible genes Bax and Gadd-45 in brain areas showing DNA fragmentation. Neuroscience. 1996;74(4):1143–1160. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee J., Son D., Lee P., et al. Alkaloid fraction of Uncaria rhynchophylla protects against N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced apoptosis in rat hippocampal slices. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;348(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shan Y., Carlock L. R., Walker P. D. NMDA receptor overstimulation triggers a prolonged wave of immediate early gene expression: relationship to excitotoxicity. Experimental Neurology. 1997;144(2):406–415. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rathore C., George A., Kesavadas C., Sankara Sarma P., Radhakrishnan K. Extent of initial injury determines language lateralization in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis (MTLE-HS) Epilepsia. 2009;50(10):2249–2255. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapur N., Ellison D., Parkin A. J., et al. Bilateral temporal lobe pathology with sparing of medial temporal lobe structures: lesion profile and pattern of memory disorder. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32(1):23–38. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakatani S., Seto-Ohshima A., Shinohara Y., et al. Neural-activity-dependent release of S100B from astrocytes enhances kainate-induced gamma oscillations in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(43):10928–10936. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3693-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manley N. C., Bertrand A. A., Kinney K. S., Hing T. C., Sapolsky R. M. Characterization of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression following a kainate model of status epilepticus. Brain Research. 2007;1182(1):138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arisi G. M., Foresti M. L., Katki K., Shapiro L. A. Increased CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, and IL-1β cytokine concentration in piriform cortex, hippocampus, and neocortex after pilocarpine-induced seizures. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2015;12(1, article 129):7. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lv R., Xu X., Luo Z., Shen N., Wang F., Zhao Y. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) inhibits the overexpression of MCP-1 and attenuates microglial activation in the hippocampus of a pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus rat model. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2014;7(1):39–45. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]