Abstract

Context

Data and best practice recommendations for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) use in adults is largely available. While there is less data in pediatric populations and no published guidelines, its practice in children continues to grow.

Methods

We performed a literature search through PubMed to review all TMS studies from 1985-2016 involving children and documented any adverse events. Crude risks were calculated per session.

Results

Following data screening, we identified 42 single pulse (spTMS) and/or paired pulse (ppTMS) TMS studies involving 639 healthy children (HC), 482 children with CNS disorders, and 84 epileptic children (EP). Adverse events (AEs) occurred at rates of 3.42%, 5.97%, and 4.55% respective to population and number of sessions. We also report 23 repetitive TMS (rTMS) studies involving 230 CNS and 24 EP with AE rates of 3.78% and 0.0% respectively. We finally identified three theta-burst stimulation (TBS) studies involving 90 HC, 40 CNS and no EP, with AE rates of 9.78% and 10.11% respectively. Three seizures were found to have occurred in CNS individuals during rTMS, with a risk of 0.14% per session. There was no significant difference in frequency of AEs by group (p = .988) nor modality (p = .928).

Conclusions

Available data suggests that risk from TMS/TBS in children is similar to adults. We recommend that TMS users in this population follow the most recent adult safety guidelines until sufficient data are available for pediatric specific guidelines. We also encourage continued surveillance through surveys and assessments on a session-basis.

Keywords: transcranial, neurostimulation, pediatric, adverse, seizure

INTRODUCTION

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive technique for cortical stimulation that uses electromagnetic induction to generate a strong fluctuating magnetic field which induces intracranial currents1. Single pulse (spTMS) and paired-pulse TMS (ppTMS) studies have been shown to be safe and effective in studying a variety of measures of motor cortex excitability including resting motor threshold, motor evoked potential amplitude, recruitment curves, cortical silent period, short interval intracranial inhibition, long interval intracranial inhibition and intracranial facilitation2. It is now a state of the art technique for studying neurophysiology in vivo. Repetitive TMS (rTMS) applies repeated TMS pulses at set frequencies or bursts of stimulation to induce changes in cortical excitability which last longer than the period of stimulus administration by minutes to hours with more durable changes in clinical outcomes reported when rTMS is given in daily sessions for 1-6 weeks3. These alterations have generally been observed as a decrease in cortical excitability with low-frequency stimulation (≤ 1 Hz) and an increase in cortical excitability with high frequency rTMS (≥ 5 Hz)3. rTMS demonstrates therapeutic potential for many conditions in adults including depression4, eating disorders5, epilepsy6, schizophrenia7, tinnitus8, 9, migraine10, and Parkinson’s Disease9,11. In children, possible therapeutic benefits have been reported for motor function and tics12, 13,14,15. Theta-burst stimulation (TBS) is a newer form of rTMS that administers 50 Hz bursts of 3 pulses every 200 msec either continuously (cTBS) or in intermittent 2-second trains every 10 seconds (iTBS)16. TBS may induce longer lasting cortical inhibition (cTBS) or excitation (iTBS) than standard rTMS16. In general, benefits when present have been of small to moderate magnitude and short-lived. Still, given the potential for clinical benefit and limitations of medical options there is a need for further studies of rTMS/TBS as a therapeutic intervention4, 8.

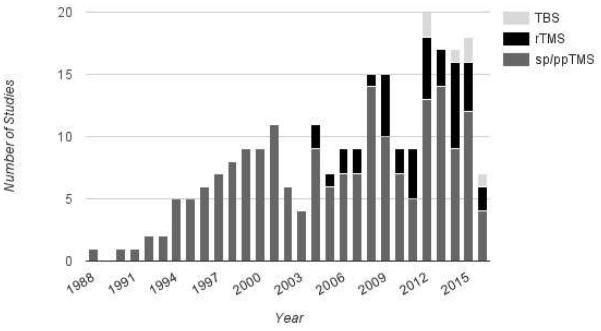

The use of TMS in both healthy and clinical adult populations has been associated with several adverse events of varying severity. The most common are transient headaches and scalp discomfort, which are thought to be due to activation of scalp pericranial muscles17, 18. However, more severe adverse effects may include mood changes, and induction of seizures17. Seizures during TMS are thought to be a result of cortical pyramidal cell activation, spread of excitation to neighboring neurons, and persistent changes in motor cortical inhibition19. Whether TMS can induce seizures is theoretically possible but controversial given the extremely rare occurrence. We wanted to provide a brief but complete review of all published studies where TMS have been used in children, and describe adverse events, in order to provide a safety profile of TMS in children for researchers and clinicians as well as safety measures for IRBs. This is of crucial importance regarding the increasing number of published studies using these tools on pediatric populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of publications each year focusing on sp/ppTMS (dark gray), rTMS (black) and TBS (light gray).

METHODS

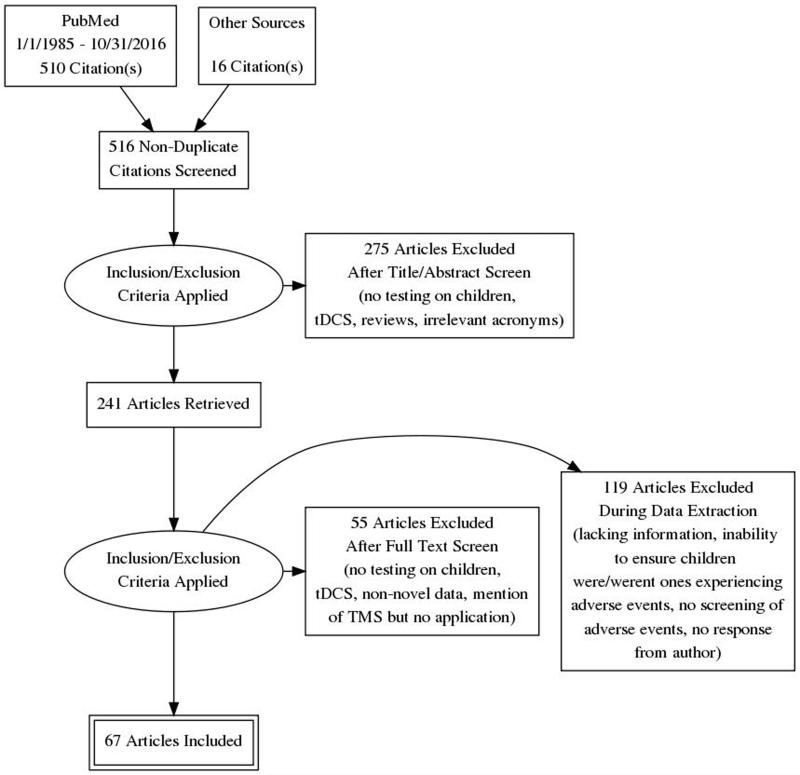

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for the conduct and reporting of this review. The different phases of this systematic review are displayed in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart using the PRISMA statement for the systematic review.

Literature Review

An extensive literature search for English language studies on TMS use in children was conducted through PubMed and links from publications from 1/1/1985 through 10/31/2016. Review articles were excluded except when presenting novel data. The searches used included the following key words: transcranial magnetic stimulation, TMS, TBS, Children, Child, Pediatric. Dealing with missing data: while our searches were comprehensive, there is a possibility that we may have missed relevant studies, however we believe this to be unlikely. We sought missing data from study authors; yet, many failed to respond. We intended to present all studies in the main report (Table 1). All applicable articles were reviewed for patient demographics (gender, age, and patient phenotype), TMS protocol used (TMS modality and stimuli intensity) and adverse events reported.

Table 1.

Description of all the studies meeting search criteria.

Rows color codes: White – No Adverse Event (AE); Lightest Gray – AE Not mentioned; Middle Gray – No access to screen Dark Gray – Adverse Events assessed and subjected to analysis.

Grading adverse events

Adverse events were graded in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v4.0)20. This commonly accepted grading scale divides adverse events into five different categories (Grade 1-5) depending on their severity. Only Grades 1-3 are present in this report. Grade 1 is a mild event that needs no intervention, Grade 2 is a moderate event with noninvasive intervention needed, and Grade 3 is a severe event, but not life-threatening, that calls for hospitalization.

Statistical Analysis

We extracted all adverse events reported in each TMS and/or TBS study. We computed the proportion estimate of crude risk per session, population, and modality. We also separated single pulse/paired pulse, rTMS and TBS studies and tested for group differences. Risks were calculated as per-session risk. Confidence intervals were calculated utilizing the Clopper-Pearson method in SPSS software version 23, and group differences were calculated via multivariate ANOVA with WLS weighting per session.

RESULTS

Studies including single and paired-pulse TMS

We identified 42 studies utilizing single or paired pulse techniques in child patients21-62. This included 639 healthy children, 482 children with central nervous system (CNS) disorders, and separately 84 epileptic children. Of these studies, 10 reported adverse events (Table 2)21, 23, 33, 37, 39, 38, 43, 48, 58, 63, and 9 were included in our calculations21, 23, 33, 37, 39, 43, 48, 58, 63. Adverse events by population were distributed as follows: 25 events in the healthy participants group, 50 events in CNS disorder participants group, and 4 events in the epileptic population. Parents of 4 epileptic children out of total 34 reported a small increase in seizures frequency following TMS, with no episode of status epilepticus48. Within 3 days after TMS, parents confirmed that seizures resumed to initial frequency ranging from 3 times per month to continuous. The risk of any adverse event during spTMS or ppTMS in healthy populations is 0.0342 (95% CI: 0.0223 - 0.0501) per session, 0.0597 (95% CI: 0.0447 - 0.0780) per session for patients with a CNS disorder, and 0.0455 (95% CI: 0.0125 - 0.1123) per session for those with epilepsy.

Table 2.

Description of adverse events.

| sp/ppTMS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year |

No. of

Individuals |

Age (yrs) | Phenotype | TMS Mode |

Paradigm and

Target |

Adverse Events |

| Hong et al., 2015 |

2015 | 89 | 6-18 | 19 Tourette’s 70 Control |

sp/ppTMS Figure 8 Coil |

MEP, RMT (60% & 120%, AMT, CSP Approximately 200 pulses per part. Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Headache (6), scalp pain (4), arm/hand/other pain (2), numbness/tingling (5), other sensations (1), nausea/vomiting (1), other (1). Moderate: Ringing in ears (1). |

| Damji et al. | 2015 | 28 | 6-18 | Healthy | spTMS Figure 8 Coil |

100-150% RMT, 0.2Hz, 7.5min Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Neck pain (1), headache (3), transient nausea (2). |

| Wu et al. | 2012 | 114 | 8-12 | 64 Control 50 ADHD |

sp/ppTMS Figure 8 Coil |

20 sp trials set at 15-30% over RMT. ppTMS of 70% RMT. Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Discomfort (15). |

| Geerdink et al. | 2012 | 78 | 6-15 | 36 Control 42 Spina Bifida |

sp/ppTMS Double Cone Coil |

100% stimulation intensity MEP. Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Discomfort (12) in controls, as well as an undisclosed number in Spina Bifida population. |

| Koudijs et al. | 2010 | 34 | 3-18 | Epileptic | sp/ppTMS Round Coil and Figure 8 Coil |

Intensity was titrated until MEP – up to max of 4T. Target: L/R Motor Cortex |

Increase in seizure frequency that subsided after three days with no intervention (4). |

| Kirton et al. | 2010 | 4 | 10-16 | Arterial Ischemic Stroke Lesions |

spTMS ppTMS Figure 8 Coil rTMS |

110 to 150% RMT or 100% MSO when no RMT 6 stimuli per level, 36 stimuli per side Target: contralateral motor cortex 100% RMT 8 days, 1 Hz 20min |

Mild: Headache (2), neck stiffness (3), nausea (3). Moderate: Neurocardiogenic syncope (2). |

| Gilbert et al. | 2006 | 16 | 8-17 | ADHD | sp/ppTMS Circular Coil |

RMT, AMT, SICI, ICF. All TMS sessions took approximately 30 minutes. Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Numbness/tingling (2), loss of appetite (2), scalp pain (1), nausea (2), stomach pain (1) and headache (5), arm/other pain (2), abdominal pain (1), hearing change (1). Moderate: Headache (1). |

| Bender et al. | 2005 | 17 | 6-10 | Healthy | sp/ppTMS Circular Coil |

105% RMT for MEPs, when RMT>MSO intensity was set to 100%. Target: Right Motor Cortex |

Mild: Discomfort (1). |

| Gilbert et al. | 2005 | 28* | < 18 | Tourette’s Syndrome (w/ ADHD/OCD in some cases) |

sp/ppTMS Circular Coil |

MEP, ISI, SICI, CSP at 130% AMT Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Discomfort (3), scalp pain (5), tiredness (4), hand or leg tingling (3), hand weakness (2), headache (1), and neck pain (1). |

| Shizukawa et al. | 1994 | 1 | 16 | Hirayama Disease | spTMS | MEP Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Dullness (1). |

| TBS | |||||||

| Hong et al. | 2015 | 76 | 6-18 | 52 Control 24 Tourette’s Syndrome |

TBS MagStim Rapid 2 |

60-90% RMT. Three pulses at 30- 50Hz, 5Hz burst freq. w/ total stimuli 300-600. |

Mild: Headache (5), numbness/tingling (2), other sensations (2), weakness (1), arm/hand/other pain (1), other (1). Moderate: Arm/hand/other pain (1). |

| Wu et al. | 2012 | 40 | 11-18 | 24 Control 16 Tourette’s Syndrome |

iTBS & cTBS Figure 8 type coil |

50Hz, 80% active MT or 90% RMT 32 sessions Target: Left Motor Cortex. |

Mild: Finger twitching (1), neck stiffness (1), headache (3). |

| rTMS | |||||||

| Cullen et al. | 2016 | 1 | 17 | Treatment Resistant Depression |

Deep TMS H-1 Coil |

18 Hz, 120% MT, 55 trains, 1980 pulses total. |

Moderate: Generalized, tonic- clonic seizure that lasted 90 seconds and resolved spontaneously (1). |

| Kirton et al. | 2016 | 45 | 6-19 | Hemiparesis | rTMS | 1 hz, 20 min 1200 stim, 1200 stimuli per session, once a day, 5 days/week, 2 weeks total. Target: Contralesional M1 |

Mild: Headache (4), nausea (1), tingling (1). |

| Gillick et al. | 2015 | 10 | 8-17 | Congenital Hemiparesis |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

6 Hz, 90% RMT, 2 5s trains/minute (total 600 pulses). Followed by 10 minutes of 1Hz, 90% RMT(600 pulses). Target: Contralesional Motor Cortex |

Mild: Headache (5), anxiety (3), dizziness (2), tingling (2). |

| Pathak et al. | 2015 | 13 | 12-17 | Bipolar Mood Disorder |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

20 Hz, 110% MT 800 daily pulses, 10 days Target: Right Prefrontal Cortex |

Mild: Headache (2) |

| Cristancho et al. |

2014 | 1 | 15 | Autism | rTMS | 90% of the RMT, 1 Hz, 10 seconds on, and 10-30 seconds off. 30 sessions in total. Target: L/R DLPFC |

Mild headaches during half of the sessions. Dizziness and jaw twitching also occurred. |

| Gomez et al. | 2014 | 10 | 7-12 | ADHD | rTMS Butterfly Coil |

90% RMT, 1Hz. 1500 stimuli/session. 1 session/day. 5 days. Target: L-DLPFC |

Mild: Headache (7), neck pain (2), dizziness (2). |

| Panerai et al. | 2014 | 35 | 11-18 | Autism | rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

90% RMT, 1Hz train (900 pulses), and 30 8Hz trains of 30 stimuli. Target: L/R Premotor Cortex |

Mild: Restlessness (1). Moderate: Rapid moodswings (1) |

| Gillick et al. | 2014 | 10 | 8-17 | Congenital Hemiparesis |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

6 Hz, 90% RMT, 2 5s trains/minute (total 600 pulses). Followed by 10 minutes of 1Hz, 90% RMT(600 pulses). Target: Contralesional Motor Cortex |

Mild: Headache |

| Yang et al. | 2014 | 6 | 15-21 | Major Depressive Disorder |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

120% RMT, 10 Hz, 75 trains (3000 pulses) Target: Left DLPFC |

Mild: Scalp discomfort, sleepiness |

| Chiramberro et al. |

2013 | 1 | 16 | Major Depressive Disorder |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

10 Hz, 120% RMT 3000 daily pulses 4 weeks of 60 trains of 5 s, 5 days/week Target: Left DLPFC |

Moderate: Tonic-clonic seizure of 30 sec on 12th day of rTMS. Patient was taking sertraline and olanzapine, and also had a high blood alcohol content. |

| Le et al. | 2013 | 25 | 7-16 | Tourette’s Syndrome |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

110% RMT, 1 Hz, 20 daily sessions (1200 stimuli daily). Target: Supplementary Motor Area |

Mild: Sleepiness (1). |

| Helfrich et al. | 2012 | 25 | 8-14 | ADHD | rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

80% RMT, 1 Hz (900 stimuli). Target: Left Motor Cortex |

Mild: Headache (3) |

| Croarkin et al. | 2012 | 8 | 14-17 | Major Depressive Disorder |

rTMS | 120% MT, 10Hz, 4s trains (3,000 stimuli per session). Target: Motor Cortex |

Mild: Scalp pain (1). |

| Hu et al. | 2011 | 1 | 15 | Adolescent Onset Depressive Disorder |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

10 Hz, 80% RMT 800 daily pulses Target: Left DLPFC |

Moderate/Severe: Tonic-clonic seizure of 1min on 1st day of rTMS, and hypomanic episode the night following the seizure. Patient follow-up indicated no further seizure. Patient was taking sertraline. |

| Kwon et al. | 2011 | 10 | 9-14 | Tourette’s Syndrome |

rTMS Figure 8 Coil |

100% RMT, 1 Hz (1,200 stimuli daily for ten days). Target: Supplementary Motor Area |

Mild: Scalp pain (1). |

| Bloch et al. | 2008 | 9 | 16-18 | Severe Resistant Depression |

rTMS Circular Coil |

80% MT, 10-Hz, 2s trains given over 20 min/d over 14 working days. |

Mild: Headache (5). |

Rows color codes: Lightest Gray – Mild AEs (or Grade 1); Middle Gray – Moderate AEs (or Grade 2); Dark Gray – Sever AEs (or Grade 3).

Number of adolescent participants is exact, whereas number of adverse events is from the entire population of the study (n=36).

Mild adverse events reported included local discomfort (n=28)23, 37, 62, headache (n=14)33, 39, 43, tingling/dullness (n=8)39, 43, 58, other pain (n=7)33, 39, 43, scalp pain (n=5)39, 43, nausea/vomiting (n=4)33, 39, 43, self-reported increase in seizure frequency for up to three days following stimulation in epileptic children (n=4)48, loss of appetite (n=2)39, hearing change (n=1)39, and other (n=2)39, 43. Moderate adverse events include headache (n=1)39, ringing of the ears (n=1)43, and neurocardiogenic syncope (n=2)21.

Studies including repetitive TMS

We identified 23 rTMS studies involving child patients13-15, 21, 64-82 including a total of 230 children with CNS disorders and 76 children with Epilepsy. There were 81 adverse events that were attributed to rTMS protocols in the CNS disorder population (Table 2). The mild adverse events were as follows: headache (n=45)15, 21, 64, 69-71, 75, 78, dizziness (n=8)66, 69, 70, jaw twitching (n=4)66, nausea/vomiting (n=4)21, 75, anxiety (n=3)69, neck stiffness (n=3)21, tingling/dullness (n=3)69, 75, scalp pain (n=2)13, 67, neck pain (n=2)70, restlessness (n=1)77, and sleepiness (n=1)14. Moderate adverse events include generalized tonic-clonic seizure (n=3)65, 68, 72 and rapid moodswings (n=1)77. The only severe adverse event to occur in rTMS stimulation is 8-9 hours of stimulation-induced hypomania (n=1)72. The risk of any adverse event during rTMS by population is 0.0378 (95% CI: 0.0301 - 0.0468) per session for individuals with CNS disorders, and 0 (95% CI: 0.0000 - 0.0070) per session for patients with epilepsy. Inside this bracket of adverse events, the crude risk of seizure for patients with CNS disorders per session is 0.0014 (95% CI: 0.0003 - 0.0041).

Studies including theta-burst stimulation

We identified three theta-burst studies involving 90 healthy children and 40 children with CNS disorders43, 62, 79. Of these studies, two identified adverse events (Table 2)43, 62. No seizures were reported, thus the crude risk of seizures is 0 (95% CI: 0.0000 - 0.0202). Nine adverse events were reported in healthy children, thus the crude risk per session is 0.0978 (95% CI: 0.0457 - 0.1776). In the population with CNS disorders, 9 mild self-limited adverse events were attributed to TBS with a crude risk per session of 0.1011 (95% CI: 0.0473 - 0.1833). The mild adverse events are as follows, and all were resolved without medical intervention: headache (n=8)43, 62, tingling/dullness (n=2)43, other sensations (n=2)43, finger twitching (n=1)62, weakness (n=1)43, other pain (n=1)43, neck stiffness (n=1)62, and other (n=1)43. There was only one moderate adverse event: arm/other pain (n=1)43.

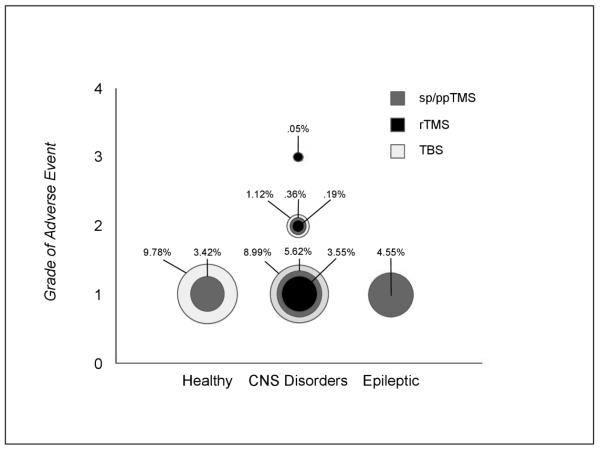

Comparing Populations and Modalities

Frequency of adverse events was similar for groups (F(6,150) =.156, p =.988) as well as modalities (F(6,150) =.316, p =.928). Frequencies per grade of adverse event, per modality, and per population are represented in figure 3. As shown, adverse events deemed Grade 1 (mild) in healthy populations, occurred at rates of 3.42% and 9.78% per session in sp/ppTMS and TBS respectively. In CNS populations, Grade 1 events occurred at rates of 5.62%, 3.55%, and 8.99% per session in sp/ppTMS, rTMS, and TBS respectively. Grade 2 (moderate) events occurred at rates of .36%, .19%, and 1.12% per session in sp/ppTMS, rTMS, and TBS respectively. Grade 3 (severe) events occurred at a rate of .05% in rTMS sessions. For Epileptic populations, Grade 1 adverse events occurred at a rate of 4.55% per session in sp/ppTMS stimulation.

Figure 3.

Frequencies per grade of adverse event, per modality, and per population.

Circle size is representative of AE frequency per session for sp/ppTMS (dark gray), rTMS (black) and TBS (light gray).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review focused on the use of magnetic currents as tools to investigate plasticity in the developing brain or to explore their therapeutic potential in children with CNS disorders or epilepsy.

While many people have worries regarding the safety of TMS in the child population, our literature review adds to previous ones showing that most adverse events are mild and overall uncommon83, 84. However, we did find three reports of new onset seizures65, 68, 72 that are lacking in similar recent reviews. In two cases, patients were diagnosed and treated for depression with sertraline which has been associated with seizures, albeit rarely85, 86. In the first case, prolonged hypomania was also reported. Hypomania is the worst grade level for adverse events in this review. While this is a unique case, hypomania is more likely a side-effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-type antidepressants such as sertraline87. In the second case65, atypical antipsychotic olanzapine was also taken by the patient on a daily basis. While antipsychotics decrease seizure threshold to varying degrees, olanzapine is known to be safer than other atypical antipsychotics considering side effects88. Still, isolated cases of olanzapine-induced clinical seizure have been reported89, 90. With multiple seizure risk factors, it is of crucial importance that TMS investigators carefully screen for medications and other potential seizure precipitants. The most recent case was an unmedicated youth with major depressive disorder treated with deep TMS68. Deep TMS uses H-coils that induce an effective field at a wider depth l compared to standard figure-8 TMS coils91. Generalized seizures in adults, as well as typical mild adverse events, have been reported during deep TMS simulation similarly as figure-8 coil stimulation92. However, deep TMS technology is new and continuous surveillance is needed due to its particular mode of action.

In regards to other moderate adverse events, the two cases of neurocardiogenic syncope were associated with pre-existing circumstances that would induce syncope. Of the two children, one failed to intake any food prior to the application and had a prior history of syncope with venipuncture, and the other had a history of early-morning presyncope with micturition and anxiety attacks21, 93. Noted as the most common adverse event related with either TMS or TBS in our literature search, mild transient headaches have been shown to be a relatively frequent side-effect of TMS and are easily quelled with acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications94. Finally, local discomfort as well as neck or arm stiffness/pain, tingling, nausea/dizziness, anxiety and discomfort are also common transient mild side-effect of TMS95.

We report one study in epileptic children where TMS induced an increase in seizure frequency up to 3 days after TMS in four children based on a phone questionnaire administered to the parents48. Epilepsy is a chronic brain disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. Current seizure frequency scales are based from continuous EEG monitoring during hospital stay. Patient or parent report questionnaires have raised concerns about their accuracy96. In the aforementioned study, children were experiencing baseline seizures at frequencies ranking from continuous to 3 per month. How accurate is a self-report of a transient increase in seizure frequency in the cases of continuous seizures or baseline seizures occurring less than once a week? The use and report of standardized scales for seizure frequency (and possibly severity) would help weighting the real adverse effect of TMS in epileptic populations.

In this review, we demonstrated that both children and adults seem to experience similar adverse events during TMS experiments. Nonetheless, because neuronal networks are the targets of the resulting electrical currents induced during the transcranial magnetic stimulation, the effects on a developing brain should be monitored carefully; the safety of TMS in child populations may thus be contemplated independently of the safety considerations in adult populations. A good example is the MEP threshold, directly related to the degree of myelination of the corticospinal tracts (i.e. the less myelinated the tracts, the higher the threshold), which decreases with age97. So, with higher motor thresholds, rTMS trials on children may be conducted at much higher output power than in adults. Adult safety guidelines on the maximum intensity may then not be appropriate for children. We suggest safety measures for children to be established through brain measures of activation and connectivity at different exposure levels (i.e. single sessions vs repetitive stimulations) as previously done in adults98, 99. Because of the temporal resolution required to assess the immediate brain changes associated with TMS or TBS, only a few modalities are able to investigate this simultaneously. Those include fMRI, EEG, MEG or functional near infrared spectroscopy. While it is not expected to include these measures in every TMS/TBS study involving children, it may be possible to monitor short and long-term effects through cognitive and behavioral assessments. While local IRBs may impose yearly reports for AEs, other changes might not be monitored by investigators yet. We suggest systematic surveys/reports to be filled out on a session-basis to monitor potential changes in behavior, health, quality of life and adverse events. These mainly include children-oriented evaluations such as The Child Behaviour Checklist100, the Child Health and Illness Profile101 and the Pediatric Adverse Event Rating Scale102. Children with epilepsy may also add the Hague Seizure Severity Scale103.

Pitfalls from conducting an exhaustive safety review for TMS use in children

First, safety data is not reported in a systematic manner which may lead to diverse biases. Under the FDA’s revised reporting requirements in 21 CFR § 882.5805/8, investigators must immediately report any serious AEs, but mild to moderate AEs are reportable to the local IRB depending on local guidelines. This results in a lack of AEs assessment and retrieval as well as incomplete data in some cases. Second, we report and grade AEs according to the most current guidelines (CTCAE v4.0; 20) which was originally designed for cancer drug trials. While pediatric oncologists raise the flag on its deficiencies104 , pediatric clinicians and researchers outside of the field of cancer may find it inappropriate. Third, efficacy and safety guidelines were addressed and published in a single paper a couple of decades ago17. This included statements that indeed were revised such as “Children should not be used as subjects for rTMS without compelling clinical reasons, such as the treatment of refractory epilepsy or depression”. There is an urgent need of criteria and guidelines applicable to children with or without epilepsy, neurological disorders and other medical conditions, as well as a systematic reporting system of AEs occurring in TMS laboratories. In this systematic review, we focused on accuracy and hope that biases from all the aforementioned issues did not deviate our main findings. In addition, we hope that this review combined with the most recent ones will help establishing appropriate guidelines for the use of TMS in children.

CONCLUSION

Over the past 30 years, over 4000 children with or without neuropsychiatric diseases have been involved in different TMS paradigms. The induction of seizures appears to be quite rare and most reported adverse events are benign. Experiments including children with epilepsy or psychiatric disorders may still require additional clinical guidance, especially screening for at-risk medications and potential seizure precipitants. Overall, the risk of TMS appears to be similar to that in adults but as the numbers of children tested increases, there is a strong need for establishing reliable guidelines applicable to pediatric populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: All phases of this study were supported by an NIH grant, 1K02NS080885-01A1 (PI: Kluger)

Abbreviations

- TMS

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- TBS

Theta-burst stimulation

- ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- MEP

Motor evoked potentials

- SICI

Short intracortical inhibition

- GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- MEG

Magnetoencephalography

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- CNS

Central Nervous System

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Contributors’ Statements:

Corey Allen carried out the literature search and the analyses, wrote and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Benzi Kluger conceptualized the study, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Isabelle Buard supervised literature search, analyses and writing process, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kobayashi M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology. Lancet neurology. 2003;2(3):145–156. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassermann EMECZUWVPTaLS . Oxford Handbook of Transcranial Stimulation. Oxford Library of Psychology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascual-Leone A, Amedi A, Fregni F, Merabet LB. The plastic human brain cortex. Annual review of neuroscience. 2005;28:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howland RH, Shutt LS, Berman SR, Spotts CR, Denko T. The emerging use of technology for the treatment of depression and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Annals of clinical psychiatry : official journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. 2011;23(1):48–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClelland J, Bozhilova N, Campbell I, Schmidt U. A systematic review of the effects of neuromodulation on eating and body weight: evidence from human and animal studies. European eating disorders review : the journal of the Eating Disorders Association. 2013;21(6):436–455. doi: 10.1002/erv.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae EH, Schrader LM, Machii K, Alonso-Alonso M, Riviello JJ, Jr., Pascual-Leone A, et al. Safety and tolerability of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2007;10(4):521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daskalakis ZJ, Christensen BK, Fitzgerald PB, Fountain SI, Chen R. Reduced cerebellar inhibition in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1203–1205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefaucheur JP, Andre-Obadia N, Antal A, Ayache SS, Baeken C, Benninger DH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vonloh M, Chen R, Kluger B. Safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in Parkinson's disease: a review of the literature. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2013;19(6):573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipton RB, Pearlman SH. Transcranial magnetic simulation in the treatment of migraine. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2010;7(2):204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fregni F, Simon DK, Wu A, Pascual-Leone A. Non-invasive brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2005;76(12):1614–1623. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.069849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mylius V, Engau I, Teepker M, Stiasny-Kolster K, Schepelmann K, Oertel WH, et al. Pain sensitivity and descending inhibition of pain in Parkinson's disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2009;80(1):24–28. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.145995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon HJ, Lim WS, Lim MH, Lee SJ, Hyun JK, Chae JH, et al. 1-Hz low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with Tourette's syndrome. Neuroscience letters. 2011;492(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le K, Liu L, Sun M, Hu L, Xiao N. Transcranial magnetic stimulation at 1 Hertz improves clinical symptoms in children with Tourette syndrome for at least 6 months. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2013;20(2):257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillick BT, Krach LE, Feyma T, Rich TL, Moberg K, Thomas W, et al. Primed low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and constraint-induced movement therapy in pediatric hemiparesis: a randomized controlled trial. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2014;56(1):44–52. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron. 2005;45(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wassermann EM. Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, June 5-7, 1996. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 1998;108(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(97)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wassermann EM, Blaxton TA, Hoffman EA, Berry CD, Oletsky H, Pascual-Leone A, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dominant hemisphere can disrupt visual naming in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37(5):537–544. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takano B, Drzezga A, Peller M, Sax I, Schwaiger M, Lee L, et al. Short-term modulation of regional excitability and blood flow in human motor cortex following rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroimage. 2004;23(3):849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute NC . NCI, NIH, DHHS. NIH publication; 2009. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. # 09-7473. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirton A, Deveber G, Gunraj C, Chen R. Cortical excitability and interhemispheric inhibition after subcortical pediatric stroke: plastic organization and effects of rTMS. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2010;121(11):1922–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babajani-Feremi A, Narayana S, Rezaie R, Choudhri AF, Fulton SP, Boop FA, et al. Language mapping using high gamma electrocorticography, fMRI, and TMS versus electrocortical stimulation. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2016;127(3):1822–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender S, Basseler K, Sebastian I, Resch F, Kammer T, Oelkers-Ax R, et al. Electroencephalographic response to transcranial magnetic stimulation in children: Evidence for giant inhibitory potentials. Annals of neurology. 2005;58(1):58–67. doi: 10.1002/ana.20521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berweck S, Walther M, Brodbeck V, Wagner N, Koerte I, Henschel V, et al. Abnormal motor cortex excitability in congenital stroke. Pediatr Res. 2008;63(1):84–88. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31815b88f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleyenheuft Y, Dricot L, Gilis N, Kuo HC, Grandin C, Bleyenheuft C, et al. Capturing neuroplastic changes after bimanual intensive rehabilitation in children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy: A combined DTI, TMS and fMRI pilot study. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;43-44:136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruckmann S, Hauk D, Roessner V, Resch F, Freitag CM, Kammer T, et al. Cortical inhibition in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: new insights from the electroencephalographic response to transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2012;135:2215–2230. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws071. Pt 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchmann J, Gierow W, Weber S, Hoeppner J, Klauer T, Benecke R, et al. Restoration of disturbed intracortical motor inhibition and facilitation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder children by methylphenidate. Biological psychiatry. 2007;62(9):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchmann J, Gierow W, Weber S, Hoeppner J, Klauer T, Wittstock M, et al. Modulation of transcallosally mediated motor inhibition in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) by medication with methylphenidate (MPH) Neuroscience letters. 2006;405(1-2):14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caramia MD, Desiato MT, Cicinelli P, Iani C, Rossini PM. Latency jump of "relaxed" versus "contracted" motor evoked potentials as a marker of cortico-spinal maturation. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 1993;89(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(93)90086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassidy JM, Carey JR, Lu C, Krach LE, Feyma T, Durfee WK, et al. Ipsilesional motor-evoked potential absence in pediatric hemiparesis impacts tracking accuracy of the less affected hand. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;47:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen TH, Wu SW, Welge JA, Dixon SG, Shahana N, Huddleston DA, et al. Reduced short interval cortical inhibition correlates with atomoxetine response in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Journal of child neurology. 2014;29(12):1672–1679. doi: 10.1177/0883073813513333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coburger J, Musahl C, Henkes H, Horvath-Rizea D, Bittl M, Weissbach C, et al. Comparison of navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative mapping in rolandic tumor surgery. Neurosurg Rev. 2013;36(1):65–75. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0413-2. discussion 75-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damji O, Keess J, Kirton A. Evaluating developmental motor plasticity with paired afferent stimulation. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2015;57(6):548–555. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galloway GM, Dias BR, Brown JL, Henry CM, Brooks DA, 2nd, Buggie EW. Transcranial magnetic stimulation--may be useful as a preoperative screen of motor tract function. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(4):386–389. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31829ddeb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garvey MA, Kaczynski KJ, Becker DA, Bartko JJ. Subjective reactions of children to single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Journal of child neurology. 2001;16(12):891–894. doi: 10.1177/088307380101601205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garvey MA, Ziemann U, Becker DA, Barker CA, Bartko JJ. New graphical method to measure silent periods evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001;112(8):1451–1460. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00581-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geerdink N, Cuppen I, Rotteveel J, Mullaart R, Roeleveld N, Pasman J. Contribution of the corticospinal tract to motor impairment in spina bifida. Pediatric neurology. 2012;47(4):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbert DL, Sallee FR, Zhang J, Lipps TD, Wassermann EM. Transcranial magnetic stimulation-evoked cortical inhibition: a consistent marker of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder scores in tourette syndrome. Biological psychiatry. 2005;57(12):1597–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilbert DL, Wang Z, Sallee FR, Ridel KR, Merhar S, Zhang J, et al. Dopamine transporter genotype influences the physiological response to medication in ADHD. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2006;129:2038–2046. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl147. Pt 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert DL, Zhang J, Lipps TD, Natarajan N, Brandyberry J, Wang Z, et al. Atomoxetine treatment of ADHD in Tourette syndrome: reduction in motor cortex inhibition correlates with clinical improvement. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118(8):1835–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glasby MA, Tsirikos AI, Henderson L, Horsburgh G, Jordan B, Michaelson C, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the semi-quantitative, pre-operative assessment of patients undergoing spinal deformity surgery. Eur Spine J. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groppa S, Siebner HR, Kurth C, Stephani U, Siniatchkin M. Abnormal response of motor cortex to photic stimulation in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49(12):2022–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong YH, Wu SW, Pedapati EV, Horn PS, Huddleston DA, Laue CS, et al. Safety and tolerability of theta burst stimulation vs. single and paired pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation: a comparative study of 165 pediatric subjects. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2015;9:29. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hufschmidt A, Muller-Felber W, Tzitiridou M, Fietzek UM, Haberl C, Heinen F. Canalicular magnetic stimulation lacks specificity to differentiate idiopathic facial palsy from borreliosis in children. European journal of paediatric neurology : EJPN : official journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society. 2008;12(5):366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung NH, Janzarik WG, Delvendahl I, Munchau A, Biscaldi M, Mainberger F, et al. Impaired induction of long-term potentiation-like plasticity in patients with high-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2013;55(1):83–89. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamida T, Fujiki M, Baba H, Ono T, Abe T, Kobayashi H. The relationship between paired pulse magnetic MEP and surgical prognosis in patients with intractable epilepsy. Seizure : the journal of the British Epilepsy Association. 2007;16(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koh TH, Eyre JA. Maturation of corticospinal tracts assessed by electromagnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. Arch Dis Child. 1988;63(11):1347–1352. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.11.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koudijs SM, Leijten FS, Ramsey NF, van Nieuwenhuizen O, Braun KP. Lateralization of motor innervation in children with intractable focal epilepsy--a TMS and fMRI study. Epilepsy research. 2010;90(1-2):140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuhnke N, Juenger H, Walther M, Berweck S, Mall V, Staudt M. Do patients with congenital hemiparesis and ipsilateral corticospinal projections respond differently to constraint-induced movement therapy? Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2008;50(12):898–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maegaki Y, Maeoka Y, Ishii S, Eda I, Ohtagaki A, Kitahara T, et al. Central motor reorganization in cerebral palsy patients with bilateral cerebral lesions. Pediatr Res. 1999;45(4):559–567. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199904010-00016. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maegaki Y, Maeoka Y, Ishii S, Shiota M, Takeuchi A, Yoshino K, et al. Mechanisms of central motor reorganization in pediatric hemiplegic patients. Neuropediatrics. 1997;28(3):168–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Narayana S, Rezaie R, McAfee SS, Choudhri AF, Babajani-Feremi A, Fulton S, et al. Assessing motor function in young children with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Pediatric neurology. 2015;52(1):94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nezu A, Kimura S, Uehara S, Kobayashi T, Tanaka M, Saito K. Magnetic stimulation of motor cortex in children: maturity of corticospinal pathway and problem of clinical application. Brain & development. 1997;19(3):176–180. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redman TA, Gibson N, Finn JC, Bremner AP, Valentine J, Thickbroom GW. Upper limb corticomotor projections and physiological changes that occur with botulinum toxin-A therapy in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. European journal of neurology : the official journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies. 2008;15(8):787–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reis J, Cohen LG, Pearl PL, Fritsch B, Jung NH, Dustin I, et al. GABAB-ergic motor cortex dysfunction in SSADH deficiency. Neurology. 2012;79(1):47–54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825dcf71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rinalduzzi S, Valeriani M, Vigevano F. Brainstem dysfunction in alternating hemiplegia of childhood: a neurophysiological study. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(5):511–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saisanen L, Kononen M, Julkunen P, Maatta S, Vanninen R, Immonen A, et al. Non-invasive preoperative localization of primary motor cortex in epilepsy surgery by navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation. Epilepsy research. 2010;92(2-3):134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shizukawa H, Imai T, Kobayashi N, Chiba S, Matsumoto H. [Cervical flexion-induced changes of motor evoked potentials by transcranial magnetic stimulation in a patient with Hirayama disease--juvenile muscular atrophy of unilateral upper extremity] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1994;34(5):500–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siniatchkin M, Reich AL, Shepherd AJ, van Baalen A, Siebner HR, Stephani U. Peri-ictal changes of cortical excitability in children suffering from migraine without aura. Pain. 2009;147(1-3):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Staudt M, Krageloh-Mann I, Holthausen H, Gerloff C, Grodd W. Searching for motor functions in dysgenic cortex: a clinical transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004;101(1 Suppl):69–77. doi: 10.3171/ped.2004.101.2.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vry J, Linder-Lucht M, Berweck S, Bonati U, Hodapp M, Uhl M, et al. Altered cortical inhibitory function in children with spastic diplegia: a TMS study. Experimental brain research. 2008;186(4):611–618. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu SW, Gilbert DL, Shahana N, Huddleston DA, Mostofsky SH. Transcranial magnetic stimulation measures in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatric neurology. 2012;47(3):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu SW, Shahana N, Huddleston DA, Lewis AN, Gilbert DL. Safety and tolerability of theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation in children. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2012;54(7):636–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bloch Y, Grisaru N, Harel EV, Beitler G, Faivel N, Ratzoni G, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression in adolescents: an open-label study. J ECT. 2008;24(2):156–159. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318156aa49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chiramberro M, Lindberg N, Isometsa E, Kahkonen S, Appelberg B. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation induced seizures in an adolescent patient with major depression: a case report. Brain stimulation. 2013;6(5):830–831. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cristancho P, Akkineni K, Constantino JN, Carter AR, O'Reardon JP. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in a 15-year-old patient with autism and comorbid depression. J ECT. 2014;30(4):e46–47. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Croarkin PE, Wall CA, Nakonezny PA, Buyukdura JS, Husain MM, Sampson SM, et al. Increased cortical excitability with prefrontal high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in adolescents with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):56–64. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cullen KR, Jasberg S, Nelson B, Klimes-Dougan B, Lim KO, Croarkin PE. Seizure Induced by Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in an Adolescent with Depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(7):637–641. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gillick BT, Krach LE, Feyma T, Rich TL, Moberg K, Menk J, et al. Safety of primed repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and modified constraint-induced movement therapy in a randomized controlled trial in pediatric hemiparesis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2015;96(4 Suppl):S104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gomez L, Vidal B, Morales L, Baez M, Maragoto C, Galvizu R, et al. Low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Preliminary results. Brain stimulation. 2014;7(5):760–762. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Helfrich C, Pierau SS, Freitag CM, Roeper J, Ziemann U, Bender S. Monitoring cortical excitability during repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with ADHD: a single-blind, sham-controlled TMS-EEG study. PloS one. 2012;7(11):e50073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hu SH, Wang SS, Zhang MM, Wang JW, Hu JB, Huang ML, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced seizure of a patient with adolescent-onset depression: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(5):2039–2044. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jardri R, Bubrovszky M, Demeulemeester M, Poulet E, Januel D, Cohen D, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to treat early-onset auditory hallucinations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(9):947–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jardri R, Delevoye-Turrell Y, Lucas B, Pins D, Bulot V, Delmaire C, et al. Clinical practice of rTMS reveals a functional dissociation between agency and hallucinations in schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(1):132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kirton A, Andersen J, Herrero M, Nettel-Aguirre A, Carsolio L, Damji O, et al. Brain stimulation and constraint for perinatal stroke hemiparesis: The PLASTIC CHAMPS Trial. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1659–1667. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Loo C, McFarquhar T, Walter G. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in adolescent depression. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):81–85. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Panerai S, Tasca D, Lanuzza B, Trubia G, Ferri R, Musso S, et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in performing eye-hand integration tasks: four preliminary studies with children showing low-functioning autism. Autism. 2014;18(6):638–650. doi: 10.1177/1362361313495717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pathak V, Sinha VK, Praharaj SK. Efficacy of Adjunctive High Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of Right Prefrontal Cortex in Adolescent Mania: A Randomized Sham-Controlled Study. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(3):245–249. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pedapati EV, Gilbert DL, Horn PS, Huddleston DA, Laue CS, Shahana N, et al. Effect of 30 Hz theta burst transcranial magnetic stimulation on the primary motor cortex in children and adolescents. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2015;9:91. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rotenberg A, Bae EH, Takeoka M, Tormos JM, Schachter SC, Pascual-Leone A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of epilepsia partialis continua. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2009;14(1):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun W, Fu W, Mao W, Wang D, Wang Y. Low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of refractory partial epilepsy. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2011;42(1):40–44. doi: 10.1177/155005941104200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Valle AC, Dionisio K, Pitskel NB, Pascual-Leone A, Orsati F, Ferreira MJ, et al. Low and high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of spasticity. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2007;49(7):534–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frye RE, Rotenberg A, Ousley M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in child neurology: current and future directions. Journal of child neurology. 2008;23(1):79–96. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krishnan C, Santos L, Peterson MD, Ehinger M. Safety of noninvasive brain stimulation in children and adolescents. Brain stimulation. 2015;8(1):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, Di Raimondo G, Di Perri R. Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold. Drug Saf. 2002;25(2):91–110. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sarkar S, Gangadhar S, Subramaniam E, Praharaj SK. Seizure with sertraline: is there a risk? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;26(3):E27–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13070146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mendhekar DN, Gupta D, Girotra V. Sertraline-induced hypomania: a genuine side-effect. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108(1):70–74. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haddad PM, Sharma SG. Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics : differential risk and clinical implications. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(11):911–936. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Behere RV, Anjith D, Rao NP, Venkatasubramanian G, Gangadhar BN. Olanzapine-induced clinical seizure: a case report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):297–298. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a7fd00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wyderski RJ, Starrett WG, Abou-Saif A. Fatal status epilepticus associated with olanzapine therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(7-8):787–789. doi: 10.1345/aph.18399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zangen A, Roth Y, Voller B, Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: evidence for efficacy of the H-coil. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116(4):775–779. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bersani FS, Minichino A, Enticott PG, Mazzarini L, Khan N, Antonacci G, et al. Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for psychiatric disorders: a comprehensive review. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kirton A, Deveber G, Gunraj C, Chen R. Neurocardiogenic syncope complicating pediatric transcranial magnetic stimulation. Pediatric neurology. 2008;39(3):196–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grazzi L. Headache in children and adolescents: conventional and unconventional approaches to treatment. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;25(Suppl 3):S223–225. doi: 10.1007/s10072-004-0291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A, Safety of TMSCG Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2009;120(12):2008–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meinardi H, Baker GA, da Silva AM. General Discussion of the Assessment and Representation of the Elements Seizure Frequency and Seizure Severity. Quantitative Assessment in Epilepsy Care. 1993;255:73–81. CJ. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garvey MA, Ziemann U, Bartko JJ, Denckla MB, Barker CA, Wassermann EM. Cortical correlates of neuromotor development in healthy children. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114(9):1662–1670. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bestmann S, Baudewig J, Siebner HR, Rothwell JC, Frahm J. Functional MRI of the immediate impact of transcranial magnetic stimulation on cortical and subcortical motor circuits. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19(7):1950–1962. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fitzgerald PB, Brown TL, Daskalakis ZJ, Chen R, Kulkarni J. Intensity-dependent effects of 1 Hz rTMS on human corticospinal excitability. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2002;113(7):1136–1141. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Achenbach TM. ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. 2001 RL. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Riley AW, Forrest CB, Starfield B, Rebok GW, Robertson JA, Green BF. The Parent Report Form of the CHIP-Child Edition: reliability and validity. Med Care. 2004;42(3):210–220. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114909.33878.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.March JS, Crisman A. The pediatric adverse event rating scale; Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 2007. KO. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carpay HA, Arts WF, Vermeulen J, Stroink H, Brouwer OF, Peters AC, et al. Parent-completed scales for measuring seizure severity and severity of side-effects of antiepileptic drugs in childhood epilepsy: development and psychometric analysis. Epilepsy research. 1996;24(3):173–181. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(96)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.de Rojas T, Bautista FJ, Madero L, Moreno L. The First Step to Integrating Adapted Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events for Children. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18):2196–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang XR, Kirton A, Wilkes TC, et al. Glutamate alterations associated with transcranial magnetic stimulation in youth depression: a case series. J ECT. 2014 Sep;30(3):242–7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]