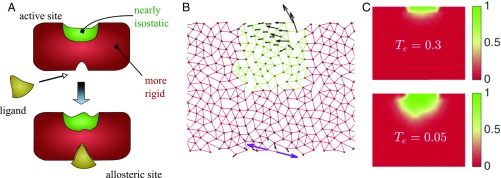

Fig. 4.

(A) Illustration of the mechanism responsible for allostery in our artificial networks. They display a nearly isostatic region in the vicinity of the active site, surrounded by a better-connected material. When the ligand binds, it induces an effective shape change at the allosteric site. This mechanical signal transmits and decays through the well-connected body of the material. It is then amplified exponentially fast in the isostatic region near the active site, leading to a large strain. (B) System made of two elastic networks with coordination (red) and (green). Its response (black arrows) to a perturbation (purple arrows) demonstrates that an isostatic network embedded in a more connected one can amplify the response near its free boundary. (C) Spatial distribution of the probability that a node is in an isostatic region connected to the active sites at and for .