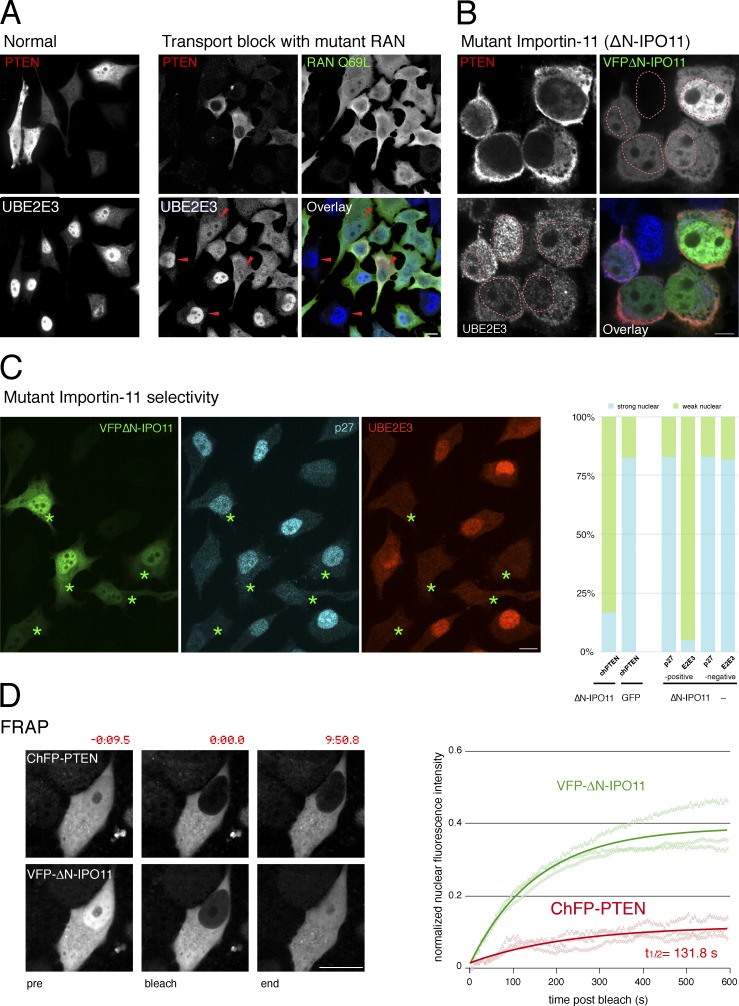

Figure 1.

Importin-11 mediates PTEN nuclear import. (A) Exogenous PTEN is both nuclear and cytoplasmic in PC3 (PTEN-null) cells (left, normal), and endogenous UBE2E3 is nuclear. Cells expressing the dominant-negative RANQ69L mutant reveal nuclear exclusion of exogenous PTEN and mislocalization of endogenous UBE2E3 (right, active transport block, arrowheads). Bar, 10 µm. Representative images of more than five independent experiments. (B) The dominant-negative ΔN-IPO11 mutant mislocalizes PTEN and a second IPO11 substrate, UBE2E3, in PC3 cells. Dashed red lines outline nuclei based on DAPI staining. Bar, 10 µm. Images represent >10 independent experiments. (C, left) Dominant-negative ΔN-IPO11 does not interfere with importin a/b–dependent nuclear import of p27Kip1 when it blocks import of the IPO11 target UBE2E3. Asterisks indicate ΔN-IPO11–positive cells. Bar, 10 µm. (right) Quantification of dominant-negative effects of ΔN-IPO11 on CherryFP-PTEN import (chPTEN + ΔN-IPO11, 54 cells, vs. chPTEN + GFP, 69 cells); P < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher exact test and quantification of ΔN-IPO11 effect on p27 and UBE2E3 in 155 ΔN-IPO11–positive compared with 157 ΔN-IPO11–negative cells. See Fig. S1 C for all absolute and relative localization counts. (D) FRAP assays show that ΔN-IPO11 blocks PTEN nuclear transport, whereas the RAN-binding mutant importin still effectively shuttles. (left) Representative images of cells at pre- and postphotobleaching and at the experimental endpoints. Time stamps (m:ss.s) relative to bleach point are indicated. Bar, 10 µm. (right) Solid lines show recovery of mean nuclear fluorescence intensity over time in a typical experiment recording three individual cells (opaque lines) in the field of view.