Abstract

The SaPIs are a cohesive subfamily of extremely common phage-inducible chromosomal islands (PICIs) that reside quiescently at specific att sites in the staphylococcal chromosome and are induced by helper phages to excise and replicate. They are usually packaged in small capsids composed of phage virion proteins, giving rise to very high transfer frequencies, which they enhance by interfering with helper phage reproduction. As the SaPIs represent a highly successful biological strategy, with many natural Staphylococcus aureus strains containing two or more, we assumed that similar elements would be widespread in the Gram-positive cocci. On the basis of resemblance to the paradigmatic SaPI genome, we have readily identified large cohesive families of similar elements in the lactococci and pneumococci/streptococci plus a few such elements in Enterococcus faecalis. Based on extensive ortholog analyses, we found that the PICI elements in the four different genera all represent distinct but parallel lineages, suggesting that they represent convergent evolution towards a highly successful lifestyle. We have characterized in depth the enterococcal element, EfCIV583, and have shown that it very closely resembles the SaPIs in functionality as well as in genome organization, setting the stage for expansion of the study of elements of this type. In summary, our findings greatly broaden the PICI family to include elements from at least three genera of cocci.

Introduction

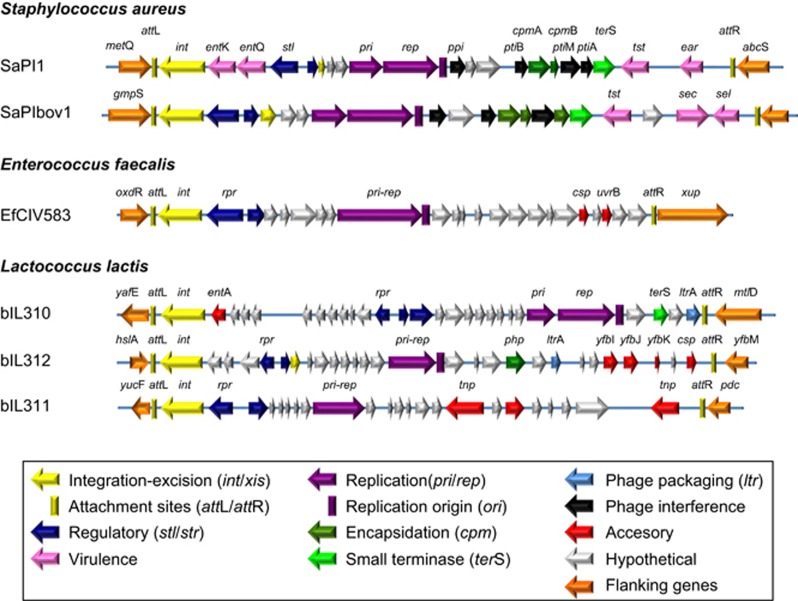

During the past several years, we have discovered and extensively characterized the SaPIs, 15 kb phage-inducible pathogenicity islands in staphylococci (reviews: Novick et al., 2010; Novick and Ram, 2015; Penadés and Christie, 2015). The SaPIs are highly evolved mobile genetic elements that are descended from an ancestral prophage or protophage, of which they have retained a number of key features that define their functionality and lifestyle. These include prophage-like transcriptional organization, SOS-insensitive repressors that are countered by helper phage-encoded derepressors, integration/excision, autonomous replication when derepressed, specific packaging in phage-derived proheads, high-frequency transfer of unlinked host genes as well as of their own genomes, and interference with phage reproduction. Their genome organization is prophage-like and consists of a small set of genes transcribed in one direction, starting with an integrase (int) gene, a somewhat larger set of genes transcribed in the opposite direction and a pair of divergent regulatory genes flanking the transcriptional switch (Figure 1). The larger transcriptional region encodes an excision function (xis), a primase homolog (pri) and a replication initiator (rep), which are sometimes fused, followed by a replication origin, the genes involved in phage interference and, usually, a terminase small subunit homolog (terS). The SaPIs have diverged radically from the putative ancestral prophage (or protophage) and occupy a unique evolutionary niche in their host bacteria. It is likely that they have maintained their evolutionary independence owing to their development of phage interference and the acquisition of hypothetical and accessory genes, none of which are phage-derived. The SaPIs form a large cohesive family with many natural Staphylococcus aureus strains containing two or more. The cohesiveness of the SaPI family is underlined by the fact that their open reading frames (ORFs) belong to large sets of orthologs, within which the first 8–10 are almost always SaPI genes, most of which never appear in other genetic elements (Novick and Ram, 2015). SaPIs are found at five different attachment sites; those in the same site are often more closely related to one another than to those in other sites. The helper phages and SaPIs undergo rapid coevolution, which is likely to have a key role in the evolution and ecology of the bacteriophages as well as of their prokaryotic hosts (Frígols et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Genome maps for PICIs and related elements. The originally identified PICIs from E. faecalis and L. lactis compared with SaPI1 and SaPIbov1. Additional details for these elements can be found in Supplementary Table S7.

Given their unique, fascinating and highly successful biological strategy, plus their importance for the biological activites of S. aureus (Novick and Ram, 2015; Penadés and Christie, 2015), it seemed highly likely that elements with similar genome organization and functionality would be found in other bacteria. The first hint of SaPI-like elements in other bacteria was provided by the genomic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis strain V583, which was sequenced by Paulsen et al. (2003) and shown to contain seven prophage-like elements. We observed that one of these, p7, has the same genome organization and is about the same size as a SaPI (Figure 1). We mentioned it in a review paper on the SaPIs and suggested that it be redesignated EfCI1 (for E. faecalis Chromosomal Island 1; Novick et al., 2010).

Later, Duerkop et al. (2012) showed that EfCI1 was cotransferred at very high frequency with phage p1. As EfCI1 was only 12 kb in length and would clearly be unable to generate infective particles on its own, the authors proposed that it and p1 formed ‘composite' particles. Soon thereafter, Matos et al. (2013), unable to demonstrate ‘composite' particles, suggested instead that EfCI1 and p1 might be similar to a SaPI-helper phage pair. They reported that p1, a fully functional temperate phage, is uniquely required for EfCI1 packaging and transfer, but unlike the SaPI-helper phages, not for induction. The authors proposed, at our suggestion, that EfCI1 be redesignated as EfCIV583, replacing the ‘1' in the generic designation, EfCI1 with ‘V583' to indicate the strain of origin, in keeping with the nomenclature that we had earlier proposed for elements of this type (Novick et al., 2010; Penadés and Christie, 2015). As p1 did not seem to be required for EfCIV583 induction, we wondered whether EfCIV583 was, in fact, fully comparable to a SaPI or, perhaps, was a new type of phage-related element. In this report, we demonstrate that EfCIV583 closely resembles a typical SaPI, requiring a helper phage for induction, packaging and transfer; however, it differs critically from the SaPIs in lacking the terminase small subunit homolog that determines packaging specificity. We demonstrate also that other low G+C Gram-positive cocci, especially the lactococci and streptococci (particularly the pneumococci), harbor large families of SaPI-like elements and that there are a few in the enterococci, very similar to EfCIV583. We designate the entire class of these elements phage-inducible chromosomal islands (PICIs), of which the SaPIs are a subset.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in these studies are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Phage and PICI analyses were performed as described (Chopin et al., 2001; Tormo-Más et al., 2013, 2010).

Identification of PICIs

The analysis of orthologies points to elements that might correspond to PICIs. Examination of the corresponding KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) genome maps (http://www.genome.jp/kegg; released 1 May 2016) was used to confirm the identifications. In these analyses, we examined only the 13 Lactococcus lactis and the 26 Streptococcus pneumoniae genomes that have been coded for KEGG because the KEGG genome maps enable PICI-like elements to be readily identified. As each of these genomes contains at least one PICI-like element, it is certain that such elements are very common among the lactococci and streptococci; additional details are given in Supplementary Materials and methods.

DNA methods

General DNA manipulations were performed as described previously (Ubeda et al., 2008). DNA probes were generated by PCR using primers listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Plasmid construction

Plasmid constructs (Supplementary Table S3) were prepared by cloning PCR products obtained with oligonucleotide primers as listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Enzyme assays

β-Lactamase assays, using nitrocefin as substrate, were performed with cells in exponential growth phase as described (O'Callaghan et al., 1972).

In-gel enzymatic digestion and mass fingerprinting

Protein bands of interest were analyzed as described previously (Tormo-Más et al., 2010).

Results

The results presented in this report are in two major subsections. The first contains an analysis of the resemblance between EfCIV583 and a typical SaPI. The second presents an extensive analysis of lactococcal and streptococcal genomes for SaPI-like elements.

E. faecalis EfCIV583

We tested the following key life cycle genes in this element: int/xis (integration/excision), rep/ori (replication initiator, replication origin) and rpr (repressor) for functionality, and noted, incidentally, that the element lacked a recognizable homolog of terS, a gene present in most SaPIs and, in those SaPIs, essential for SaPI-specific transfer (Ubeda et al., 2007b). We also identified the p1 gene that is responsible for EfCIV583 induction.

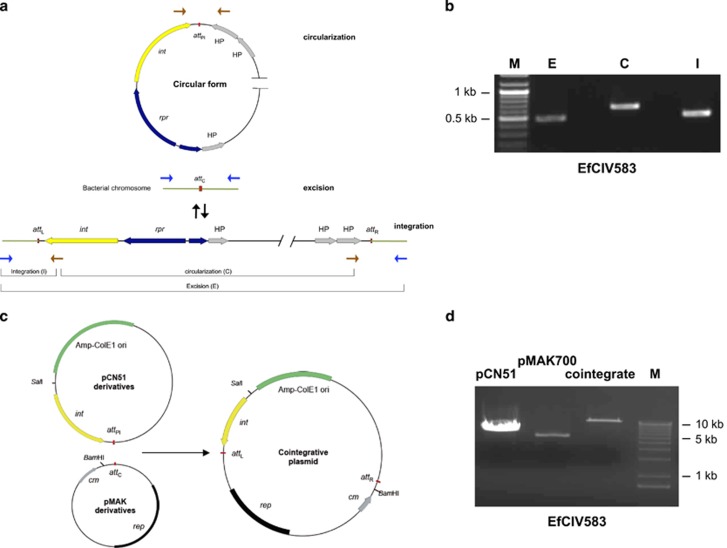

Integration/excision

To confirm the functionality of the int/xis system of EfCIV583, we performed PCR analysis with inward- and outward-directed primers as shown in Figures 2a and b. In both cases, amplicons were obtained, suggesting int functionality. To confirm this, we analyzed int activity ectopically in Escherichia coli. We prepared derivatives of the thermosensitive plasmid pMAK700 (Hamilton et al., 1989) containing the chromosomal attachment site (attC) for EfCIV583 and derivatives of pCN51 (Charpentier et al., 2004), containing the cognate PICI attachment site (attPI) plus int (Figure 2c). Plasmid pairs were tested for cointegrate formation by overnight growth (at 30 °C) followed by plating on doubly selective medium at 43 °C, the restrictive temperature for pMAK700. Colonies were obtained only with plasmids containing the cognate att sites and int gene; no colonies were obtained when the att sites and int genes were from different elements. Cointegrate formation was confirmed by restriction analysis (Figure 2d), and by plasmid sequencing.

Figure 2.

Characterization of EfCIV583-encoded Int protein. (a) Schematic representation of the EfCIV583-dependent excision and circularization processes. The relevant genes, genetic markers and PCR primer binding sites are shown. (b) Detection of EfCIV583 excision and circularization. DNA from E. faecalis VE14089 was extracted and PCR-amplified using specific primers (see scheme in a) recognizing the external and internal sequence of the element (integration: I), primers recognizing the flanking sequences (excision: E) or PCR-amplified using a pair of primers set divergently at both termini of the island (circularization: C). M: molecular weight marker. (c) Constructs used for test site-specific integration in E. coli. Top: pCN51 derivatives containing the EfCIV583 attPI-int gene. Bottom: thermosensitive derivatives of pMAK700 carrying the attC from the E. faecalis chromosome. The relevant genetic markers and restriction enzyme sites are shown. (d) Plasmid DNA was isolated from overnight cultures grown at 37 °C (for strains carrying uniquely the pCN51 or pMAK700 derivatives) or at 43 °C (for strain carrying both plasmids), in the presence of ampicillin (pCN51) or chloramphenicol (pMAK700 derivative and cointegrative plasmid). Plasmids were digested with BamHI (pMAK700 derivatives) or with SalI (pCN51 derivatives and cointegrative plasmids).

Replication

The Pri-Rep-ori segment of SaPIbov1, SaPI1 or SaPIn1 can drive replication of a suicide plasmid in S. aureus (Ubeda et al., 2007a, 2008). As the EfCIV583 replicon seemed to have the same overall organization as the SaPIs (see Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1A), we tested for functionality of its replicon by cloning the corresponding segment of EfCIV583 (plasmid pJP782) into an erythromycin resistance (Emr) plasmid containing the E. coli ColE1 replicon (incapable of replication in S. aureus or other Gram-positive bacteria). We also constructed plasmids carrying mutations in the rep gene or in the ori site (plasmids pJP1306 and pJP781) of EfCIV583. As controls, we used similar plasmids carrying the replication module from SaPI1 or SaPIbov1 (plasmids pRN9217 and pRN9211, respectively). Plasmids were transferred to S. aureus RN4220, E. faecalis JH2-2 and Bacillus subtilis RL-3 by transformation with selection for the EmR marker of the plasmid. Additionally, as staphylococcal phages can transfer SaPIs and plasmids to Listeria monocytogenes (Chen and Novick, 2009; Chen et al., 2015a), we transduced the functional plasmids from S. aureus to this organism, also with erythromycin selection. Plasmids carrying the pri-rep-ori segment, but not those with mutations in these loci, produced colonies in the recipient strains (Table 1). DNA extraction from the different hosts confirmed the presence of the plasmids containing the replication module (Supplementary Figure S1B). These results confirm that EfCIV583, SaPI1 and SaPIbov1 can replicate in different Gram-positive bacteria, and that this replication depends on the presence of a functional replicon.

Table 1. Characterization of the PICI-encoded replicon.

| PICI replicon | Recipient strain |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. faecalis | L. monocytogenes | B. subtilis | |

| SaPI1 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| SaPIbov1 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| EfCIV583 | +++ | +++ | +++ | − |

Abbreviation: PICI, phage-inducible chromosomal island.

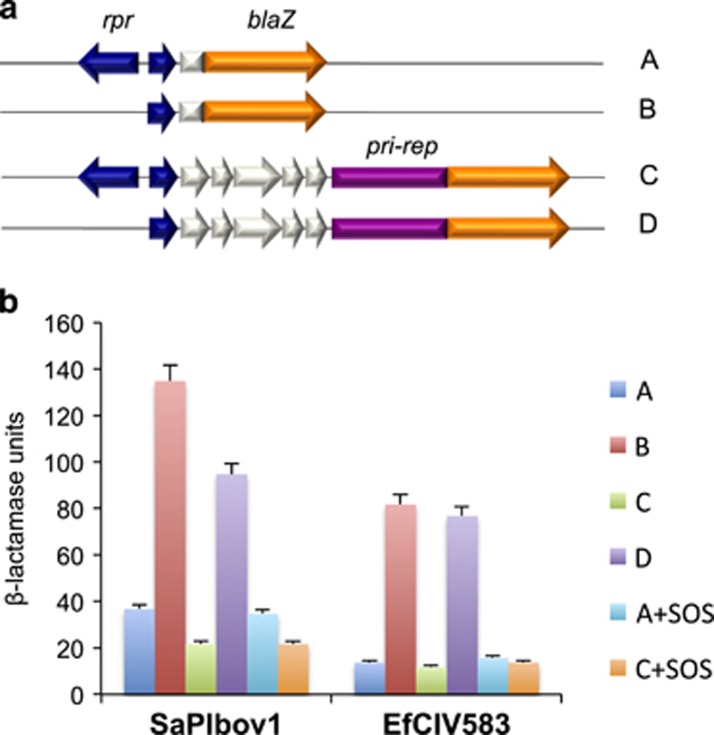

Functionality of EfCV583 master repressor

SaPI gene expression is controlled by a master repressor, Stl, analogous to λ-c1 (Ubeda et al., 2008). To test for a comparable repressor in EfCIV583, we cloned into a β-lactamase reporter vector, pCN41 (Charpentier et al., 2004), the region of EfCIV583 corresponding to the SaPI regulatory region, which contains stl, the promoter that it represses and the site of transcriptional divergence (Ubeda et al., 2008; Tormo-Más et al., 2010). Clones were constructed in E. coli either with or without the stl-like gene, which is here designated rpr (repressor; see Figure 3a); the reporter constructs were introduced by transformation in S. aureus RN4220, and β-lactamase activities were measured. The clone containing rpr showed sharply lower β-lactamase activities than that lacking it, consistent with repressor function for Rpr (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the EfCIV583-encoded Stl repressor. (a) Schematic representation of the different blaZ transcriptional fusions. The relevant genes are shown. (b) S. aureus RN4220 strains containing the plasmids represented in a were assayed for β-lactamase activity under standard conditions, or after MC induction. Samples were normalized for total cell mass. Values are presented are the averages (±s.d.) of three independent assays.

Identification of the phage p1-coded EfCIV583 inducer

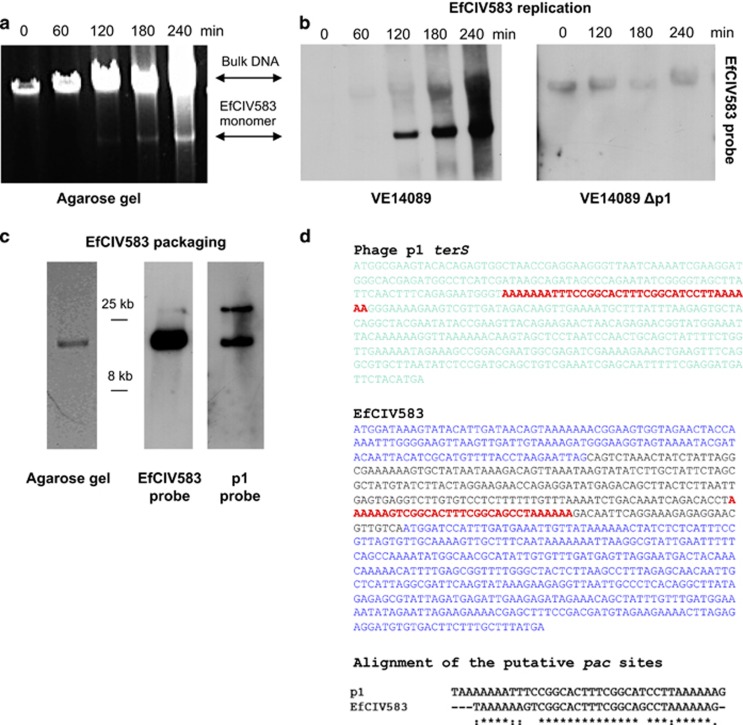

Since p1 did not seem to be required for EfCIV583 induction, we wondered whether EfCIV583 was, in fact, fully comparable to a SaPI or, perhaps, was a new type of phage-related element. Accordingly, we subjected the element to the two tests by which the original SaPIs had been defined. First, we SOS-induced strain VE14089 with mitomycin C (MC), removing aliquots of the culture at different times during induction. VE14089 is a plasmid-cured derivative of strain V583 (Supplementary Table S1), which facilitates the interpretation of agarose gels used for the analysis of EfCIV583. The cells were lysed with lysozyme and the lysates analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. In the SaPI system, in an experiment of this type, late in the lytic cycle, a new band appears in the electropherogram, migrating more rapidly than the sheared chromosomal (bulk) DNA (Lindsay et al., 1998; Ubeda et al., 2005). This band has the mobility of the SaPI monomeric DNA and represents SaPI DNA released from intracellular mature small particles or filled small proheads during preparation of the DNA sample (Ubeda et al., 2007b, 2008). As shown in Figure 4a, the gel pattern observed with VE14089 following phage induction was indistinguishable from that seen with the classical SaPIs (Lindsay et al., 1998; Ubeda et al., 2005), and the identity of the SaPI-like band was confirmed as EfCIV583 by Southern blotting (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Induction of EfCIV583 by MC. MC (1 μg ml−1) was added to a culture of E. faecalis VE14089 (EfCIV583-positive) or E. faecalis VE14089 Δp1, followed by incubation at 32 °C. Samples were removed at the indicated time points and used to prepare minilysates, which were resolved on a 0.7% agarose gel (a), and Southern blotted with an EfCIV583 probe (b). In panel (c) is a stained gel and a Southern blot of DNA extracted from phage particles in a lysate of an MC-treated culture of VE14089. (d) The putative p1 pac site (colored in red) is embedded in the terS gene (colored in green). Its homolog in EfCIV583 is located between two genes (colored in blue). See text for explanation. Bottom: The predicted EfCIV583 and p1 pac sites are aligned using ClustalW2. A full-colour version of this figure is available at the ISME Journal Online.

The second test involved the pelleting of the particles in an MC-induced VE14089 lysate and isolation of the particle DNA followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. With a SaPI-helper phage combination, two bands are seen with such DNA—one of phage monomer size and the other of SaPI monomer size (Ubeda et al., 2007b; Tormo et al., 2008). Again, as shown in Figure 4c, the same gel pattern was seen with EfCIV583 and confirmed by Southern blotting. These results imply that EfCIV583 is packaged in small capsids as are many of the SaPIs (Ruzin et al., 2001; Ubeda et al., 2005); indeed, such small particles have been observed by Matos et al. (2013). The sequence of EfCIV583, however, does not contain any identifiable homologs of the SaPI cpm or ccm genes, which are responsible for small particle formation (Ubeda et al., 2007b; Carpena et al., 2016), and we are presently attempting to identify such genes by mutational analysis.

To test further the implication that EfCIV583 and p1 represent a SaPI-like element and its helper phage, we introduced a selectable marker (tetM) into a putatively non-essential region of EfCIV583 (Supplementary Figure S2), then prepared an MC-induced lysate of JP11028, containing this derivative and phage p1, and tested for transfer of the tetM marker to two different non-lysogenic E. faecalis strains. Transfer of the tetM marker was observed at a frequency of up to ~105/ml (Table 2), three orders of magnitude greater than would be expected for generalized transduction. Incidentally, sequencing of the DNA obtained from phage particles in these experiments revealed that the individual phage or PICI elements are packaged independently, confirming the absence of any fused p1/EfCIV583 genome.

Table 2. Effects of phage mutants on EfCIV583 transfera.

| Donor strain |

Recipient strainb |

|

|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | VE18590 | JH2-2 |

| V583 wt | 8.9 × 104 | 1.9 × 102 |

| V583 Δφ1c | <1 | <1 |

| JP11028d | 5.6 × 104 | 2.4 × 102 |

| JP13142e (p1 Δxis) | <1 | <1 |

Abbreviation: xis, excision function.

The means of results from three independent experiments are presented. Variation was within ±5% in all cases.

Transductants per ml of lysate, using the non-lysogenic VE18590 or JH2-2 as recipient strains.

Phage deleted in strain V583.

JP11028: Lysogenic for phage p1; EfCIV583-positive.

JP13142: Derivative of JP11028, p1 Δxis mutant.

To confirm that p1 is the helper phage for EfCIV583, using pMAD derivative plasmids (Supplementary Table S3), we cured VE14089 of prophages 1–6. We found that the elimination of p1 but not any of the others eliminated EfCIV583 transfer (in accordance with Matos et al., 2013), as well as the appearance of the PICI band following MC induction (Figure 4b and Table 2). Moreover, MC treatment of a non-lysogenic EfCIV583-positive strain did not show either induction or any extra chromosomal species of the EfCIV583 element (Supplementary Figure S3A). Although these results clearly confirm that p1 is required for the induction and packaging of EfCIV583, they raise a further question of the packaging mechanism, since, as noted above, EfCIV583 does not encode a recognizable terS gene. We therefore considered the possibility that, like SaPIbov5 (Quiles-Puchalt et al., 2014), EfCIV583 contains a packaging site that is recognized by the p1 terminase. Since the terminase packaging (pac) site for most phages is embedded in the terS coding sequence, we performed a blast search with the p1 terS coding sequence looking for a matching subsequence within EfCIV583. As shown in Figure 4d, we found such a sequence and suggest that it represents the requisite packaging site for both phage and PICI, and therefore that EfCIV583 uses the p1 terminase for its packaging. This sequence, as occurs with the SaPIs (Quiles-Puchalt et al., 2014), is located in an intergenic region of EfCIV583 (Figure 4d). A BLAST search showed that this sequence was present in the terS gene of two additional E. faecalis prophages and, remarkably, in a pneumococcal PICI, SpnCI670-6B-1.

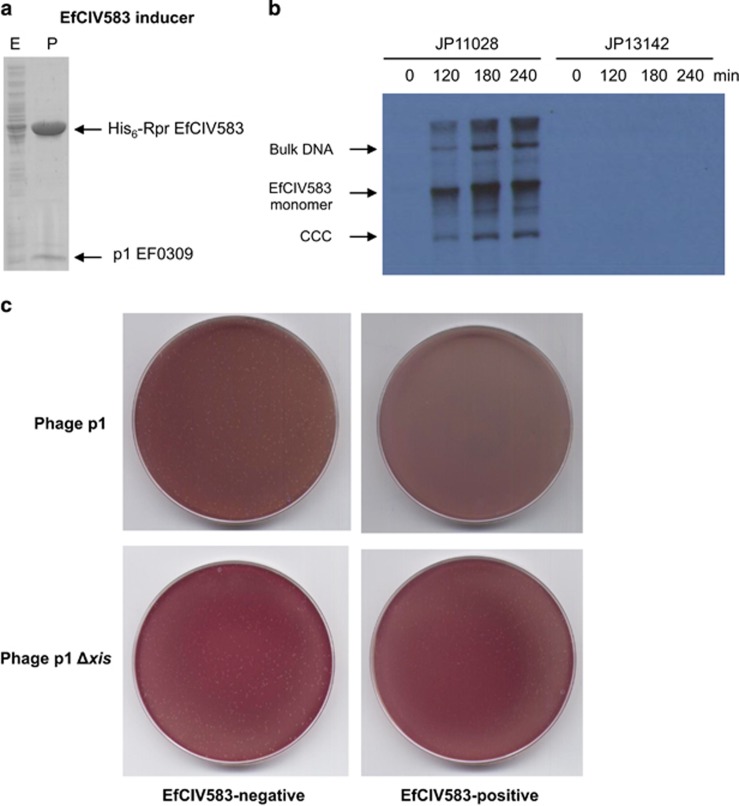

The existence of a functional Stl-like repressor of EfCIV583 replication, plus the failure of MC to induce the appearance of replicative forms of EfCIV583 in a non-lysogen suggested that, like the SaPI Stl, the EfCIV583 repressor Rpr is SOS-insensitive. We confirmed the SOS insensitivity of the EfCIV583 repressor by means of the β-lactamase reporter fusion, as shown in Figure 3. As the most likely source of the putative derepressor protein was the helper phage p1, we subcloned several segments of the phage, tested them for induction of EfCIV583 with the β-lactamase reporter fusion (Supplementary Figure S3B), and found that a 4.5 kb phage segment could relieve Rpr-mediated repression of the β-lactamase reporter fusion (Supplementary Figures S3C and D). We were then able to demonstrate that a single gene in this segment (EF0309; Supplementary Figure S3E) was responsible, and that a p1 derivative with a mutation in this gene did not induce transfer of the element (Table 2). We then used affinity chromatography with a histidine-tagged derivative of Rpr to test for the formation of a complex between the phage-encoded inducer and the EfCIV583-encoded repressor (Figure 5a), as previously reported for the SaPIs (Tormo-Más et al., 2010). These results suggested that the product of EF0309 acts directly on the repressor, as previously reported for the well-characterized Dut-specific induction of the SaPIs (Tormo-Más et al., 2010, 2013). Interestingly, an orthology analysis of EF0309 revealed that it is highly likely to be the phage's xis gene, and it is referred to as xis hereafter.

Figure 5.

Identification of the EfCIV583 inducer. (a) Affinity chromatography of p1 EF0309 using His6-RprEfCIV583. E. coli strain expressing the EF0309/His6-RprEfCIV583 pair was IPTG (isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside)-induced and, after disruption of the cells, the expressed proteins were applied to a Ni2+ agarose column and eluted. The presence of the different proteins was monitored in the load (lanes E), flow-through, wash and elute fractions (P) by Coomassie staining. The identity of the purified proteins was determined by in-gel enzymatic digestion and mass fingerprinting. It is assumed that the presence of Xis in the eluate represents an Rpr–Xis complex. (b) MC (1 μg ml−1) was added to a culture of E. faecalis JP11028 (EfCIV583/p1-positive) or E. faecalis JP13142 (JP11028 p1Δxis), followed by incubation at 32 °C. Samples were removed at the indicated time points and used to prepare minilysates, which were resolved on a 0.7% agarose gel, and Southern blotted with an EfCIV583 probe. (c) EfCIV583 interference with phage reproduction. Approximately 108 bacteria (carrying or not the EfCIV583 element) were infected with 400 plaque forming units (PFU) of phage φ1 or phage p1 Δxis, plated on phage bottom agar and incubated 24 h at 32 °C. Plates were stained with 0.1% triphenyl tetrazolium chloride in TSB (tryptic soy broth) media and photographed. CCC, closed circular form.

Finally, the role of Xis in EfCIV583 induction was confirmed by the introduction of an in-frame xis deletion in p1, which also eliminated EfCIV583 induction, mobilization and EfCIV583-mediated phage interference (Figures 5b and c and Table 2).

In summary, EfCIV583 appears to closely resemble a typical SaPI, with p1 serving as its helper phage. Our results however, are inconsistent with those of Matos et al. (2013), who reported that, unlike the SaPIs, EfCIV583 can be SOS-induced and that EfCIV583 and p1 are each packaged exclusively in small and large particles, respectively. In both cases, however, our data do not agree with those of Matos et al. (2013). First, we could not demonstrate SOS inducibility and we show, rather, that EfCIV583 is induced by the phage-coded Xis protein (see Figures 3 and 5). Second, since in the Southern blot analyses the p1 and EfCIV583 probes hybridized both with the EfCIV583-sized (small) and the phage-sized (large) DNA bands (Figure 4c), our results suggest that phage DNA can be packaged in the EfCIV583-sized particles, and conversely the island DNA can also be packaged in full-sized phage particles. As with the SaPIs, these results indicate that packaging is not dependent on prohead size (Maiques et al., 2007; Ubeda et al., 2007b). Packaging of a significant proportion of phage DNA in the small particles, which would generate defective phages, could be responsible for the observed phage interference (Matos et al., 2013; Frígols et al., 2015).

Extension to other Gram-positive cocci

Genomic analyses

A key feature of the present study is that we considered it important to focus on species in which cohesive families of SaPI-like elements could be identified and in which these were the predominant form of phage-related elements in the genus. This would be, first of all, parallel to the S. aureus situation and secondly would reinforce the concept that the biological success of such elements would be underlined by the existence of large—possibly exclusive—intrageneric families. Although the first PICI element was identified in E. faecalis, it subsequently became clear that E. faecalis does not contain a significant family of such elements. Thus, only four others have been identified and all are very closely related (Supplementary Figure S4 and Supplementary Table S4), three of them being in the same site as EfCIV583. Moreover, the orthology analysis of the EfCIV583 ORFs does not reveal membership in any family (see Supplementary Table S5). Nevertheless, EfCIV583 shares not only most of the functional features of a typical SaPI but also the typical genome organization, indicating that that it is clearly a member of the overall PICI family, as described above, despite the atypical pattern of its orthologs.

By contrast, in the lactococci and the streptococci (especially Streptococcus pneumoniae), there does appear to be a series of elements that fits the genomic pattern described for the SaPIs. These elements, which form cohesive families on the basis of ortholog analysis (see below), could readily be separated from other types of inserted elements, occupying specific and unique chromosomal sites. In this report, we characterize these cohesive families of SaPI-like elements, the lactococcal and streptococcal PICIs.

Lactococcal PICIs

Identification and genomic characterization

For the lactococci, we started with two reports describing six ‘prophage' genomes in L. lactis strain IL1403 (Bolotin et al., 2001; Chopin et al., 2001). Three of these, bIL309, bIL285 and bIL286, are typical prophage genomes, 35–44 kb in length and three, bIL310, bIL311 and bIL312, are much smaller, 11–15 kb, and lack virion protein genes. Two of the three, bIL310 and bIL312 (but not bIL311), are apparently inducible as their DNA could be detected in lysates after MC induction of the resident prophages present in strain IL1403 (Bolotin et al., 2001). The genomic patterns of these three were highly similar and were also highly similar to the genomic patterns of the SaPIs, as noted above (see Figure 1).

To identify similar elements in other lactococci, we used the KEGG orthology tool (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000). Here, we started with the phage-related element present in the strain CV56 (LlCIV56-1), which is similar to bIL310 in IL1403 (henceforth, LlCI-lL1403(I)), and generated orthology lists for all 22 ORFs in the island (Supplementary Table S6). The orthologs are listed in decreasing order of similarity to the index gene, and the length of the list depends on how well the gene is conserved. Each gene in the list is linked to a KEGG map of the corresponding region of the organism's genome, and the KEGG map patterns are often highly informative with respect to the local genetic context. Indeed, visual inspection of the KEGG genome map usually enables the identification of such inserted elements. For example, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5A and described above for the SaPIs, a PICI consists of a short set of genes transcribed in one direction and a longer set transcribed in the opposite direction, with the overall size being ~12–16 kb. The int gene is at or near the end of the shorter set, the terS gene near the end of the longer set, within which are one or two large genes corresponding to rep and pri, and the divergence is flanked by regulatory genes corresponding to SaPI stl and str. A typical example is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S5A. Visual scanning of the entire genome often reveals one or more other elements with this pattern or with the prophage pattern (Supplementary Figure S5B); in the staphylococci, streptoocci and lactococci, other types of inserted elements, aside from transposons and insertion sequences, are very rare (although sets of genes with this overall pattern can be found, BLAST searches readily determine whether these are inserted elements such as PICIs or not). PICIs and prophages have small numbers of specific att sites and once these are identified, BLAST searches with the flanking genes reveal the unoccupied sites, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5A.

In the ortholog Tables, generally at least the first 10 orthologs are listed. Occasionally, orthologs are found in the absence of other PICI- or prophage-related genes. These are listed as ‘no insert'. Where there are fewer than 10, either all the matches are listed or prophage genes have begun to appear (and are listed), at which point the list is terminated. The left-hand column in the chart records the locus tag of the gene that has been identified by the KEGG orthology search. In the next three columns are the length of the hypothetical protein (HP), its % similarity with the index protein, and the length of the overlap region between the two that was used for the similarity calculation. For each of the orthologs listed, the corresponding genome region was inspected to determine the type of insert, if any, in which the gene was located. This result is listed in the next column. If it resembles the genomic pattern of a typical PICI or prophage (see below), this is so indicated. ‘NI' (no insert) means that the flanking regions do not have the pattern of genes typical of PICIs, prophages or other mobile elements, nor do the flanking genes resemble genes of mobile elements. The next two columns indicate the coordinates of the ends of the putative inserted element, and the next, its size. Any relevant comments are in the next column. Several problematical elements, listed as ‘hybrid', probably represent hybrids between PICIs and prophages. They represent additional examples of possible recombinants and are included for completeness.

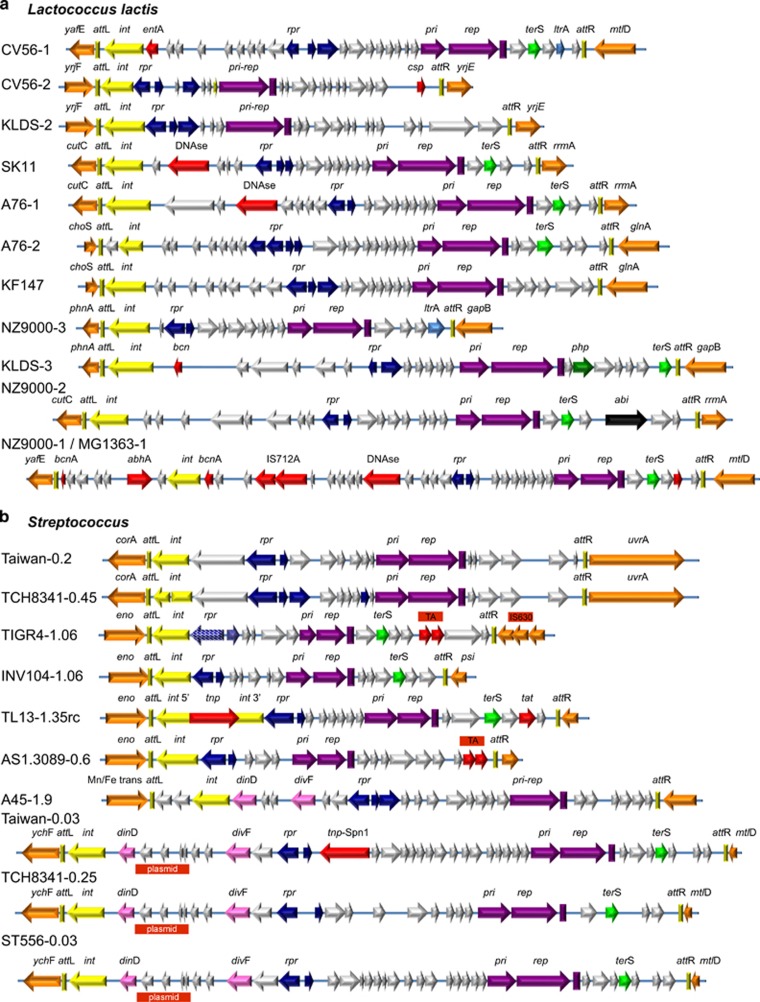

By this means, we identified a set of 26 SaPI-like elements in the lactococci, and observed that they occupy seven different att sites (Supplementary Table S7 and Supplementary Figure S6). These elements, like those in IL1403, have a number of features in common with the SaPIs: (i) unique attachment (att) sites that are not also occupied by prophages; (ii) the above-mentioned major point of transcriptional divergence flanked by regulatory genes (also a feature of temperate phages); (iii) absence of bacteriophage morphogenetic and lytic genes; (iv) size around 15 kb; and (v) presence of primase (pri) and initiator (rep) protein genes, plus location and organization of the replication origin. Although the Pri-Rep proteins are often annotated, remarkably, as virulence-related proteins (VapE) or as phage resistance proteins, the genes encoding these proteins are always homologous to the SaPI replication initiation genes (Ubeda et al., 2007a) and are indicated as such in our maps. Of note is the fact that, as with the SaPIs, distinct families of PICI Pri-Rep proteins are encoded in these elements. Thus, in some cases, the pri-rep genes are fused as is the case with some SaPIs. A subset of these newly identified lactococcal PICIs is illustrated in Figure 6a. Their ORFs are color coded to indicate putative functions, and, as can be seen, their organization corresponds closely to that seen in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S5A.

Figure 6.

PICI genomes. (a) L. lactis PICI genomes identified by searching with b3IL10 genes, arranged by att sites. Also shown is a highly unusual element from L. lactis KF147, which may be related to integrative and conjugative element (ICE) elements and plasmids, as it has an integrase plus putative plasmid replication and segregation genes. It could be confused with a PICI, except that its transcriptional organization does not fit. (b) Genomes of PICIs of S. pneumoniae and other streptococci. The color coding of the PICI genes is the same as in Figure 1.

A problem with the assembly and characterization of these element families is that the overall recombination frequency in lactoccoci is high, and consequently, genomic rearrangements are common; to pinpoint possible rearrangements, it is especially important to have a family of closely related elements for comparison. An example of genotypic modifications is provided by the elements at the mtlD site in L. lactis (site I). Among the currently available sequenced genomes, four have PICIs at this site, NZ9000, MG1363, IL1403 and CV56. The first two (LlCINZ9000-1 and LlCIMG1363-1) are virtually identical in sequence as are the latter two (bIL312 and LlCICV56-1), and a comparison of the first (LlCINZ9000-1) and third (bIL310) elements reveals several areas of virtual identity separated by three major unshared segments, which are most likely to be insertions. At the extreme 5′ end is a 4 kb unshared region that is also present at the insertion site in strain KW2 and, in a modified form including a transposon, in strain SK11, and is absent in strain KLDS.

As can be seen in the Supplementary Table S6, for most of the 22 ORFs examined, the top 10 orthologs belong to other putative PICIs. Prophages appear toward the end of the list, but mostly for those ORFs that are obviously phage-related (int, pri, rep or terS), and in all cases, the phage ORFs have low similarity with the PICI gene. The other types of ORFs in the list include: (i) accessory genes that were presumably inserted by some unknown type of recombination event and (ii) ORFs encoding HP.

HP analysis

As with most genetic units, the newly identified PICIs always contain many ORFs with unknown functions, whose putative products are annotated as HPs. There are several orthology patterns among the HPs: some HPs are highly conserved and present in many different PICIs, but never elsewhere, whereas others are specific to one or two PICIs only. Prophage orthologs are rarely found, usually very far down when there is a long list. In these cases, the gene may have originated in a prophage or have been acquired by one. We suggest that HPs matching only conspecific PICIs have either been acquired since the divergence of PICIs from their ancestral element or have evolved de novo. Either underscores the long evolutionary independence of these elements. Although the HP ORFs found only in PICIs may be free to diverge unrestrictedly, we have not encountered any that have recently been fragmented by mutation and they nevertheless retain their exclusive membership in the PICI family, supporting the concept that the family is coherent and that its members have evolved independently and in concert.

Packaging of the lactococal elements

We have recently reported that some SaPIs have cos sites. These variant SaPIs, of which SaPIbov5 is the prototype (Viana et al., 2010), are induced by cos phages, which share the same cos site, and are efficiently packaged by these phages, leading to high-frequency intra- and intergeneric transfer (Quiles-Puchalt et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015a). Since all three phages present in L. lactis IL1403 are cos phages, and since the bIL310 and bIL312 elements present in this strain can be packaged after induction of the resident prophages (Bolotin et al., 2001), we hypothesized that these elements use for packaging the same strategy used by SaPIbov5, namely carrying the cos sequence present in one of the prophages. To test this, we analyzed the sequence contained between the hnh and the terS phage genes. In many phages from Gram-positive bacteria, this region contains the phage cos site (Quiles-Puchalt et al., 2014). Examination of the bIL310 sequence revealed a putative cos site identical to the putative phage bIL286 cos site (Supplementary Figure S7). Related with the other two phages present in the L. lactis IL1403 strain, bIL285 and bIL309, other PICIs also share the putative cos sites present in these phages (Supplementary Figure S7). To test these phage cos sites for function, we cloned the bIL286 and bIL310 putative cos sites to a plasmid, pAGEnt (Supplementary Table S3), which was not transferrable after induction of the resident prophages present in strain IL1403, and found that the cloned cos sites enabled transfer of the plasmids by the bIL286 phages (Supplementary Table S8). This result confirmed the identity of these sequences as cos sites.

Pneumococcal and other streptococcal PICIs

A similar search in eight of the now very large number of pneumococcal genomes revealed essentially the same pattern of SaPI-like elements as in the lactococci. Diagrams of the genomes of 10 of these are presented in Figure 6b and Supplementary Table S7. We have also carried out an orthology analysis for all of the ORFS in one of these, in strain 670-6B, at 0.01M b (ychF site). The results of this analysis, shown in Supplementary Table S9, are similar to those obtained in the analysis of the lactococcal elements (Supplementary Table S6), confirming the idea that the PICI genes belong exclusively to the PICI elements. The difference with the lactococcal elements is that in the pneumococcal PICIs some orthologs are found frequently among other streptococci and orthologs that do not belong to any inserted element are sometimes found in a wide variety of other genera—which may be a result of the high level of transformation competence in pneumococci and related streptococci (Straume et al., 2015). As with the lactococci, with one exception, prophages do not appear or only appear far down the list. The exception is gene SP670_0020, an ORF encoding a 55 amino-acid HP, for which the first three orthologs are three different prophages. These prophages are at different sites in three different host strains, and none of these sites contains a PICI. This ORF presumably represents a very rare episode of gene exchange between PICIs and prophages.

The appearance of other streptococci in this list suggests either that the PICI lineage split from an ancestral element before the differentiation of streptococcal species, or reflects horizontal transfer of these elements. Transfer, however, need not have been mediated by a helper phage, as these streptococci are transformation competent, and pneumococci have a habit of extruding their DNA under certain conditions (Claverys et al., 2007). It is especially notable that a site 3′ to the enolase gene is occupied by closely related PICIs in Streptococcus suis and Streptococcus oligofermentans, as well as in S. pneumoniae (see Figure 6b and Supplementary Table S7).

Examination of KEGG genome maps obtained with orthologs of the rep gene of LlCI1403(I) revealed similar elements in many species. In the pneumococci, only elements of the PICI type were identified in this screen. We thus considered it likely that these elements would belong to a pneumococcus-specific family analogous to those in S. aureus and in the lactococci. We have identified 11 different att sites for the pneumococcal PICIs. As our analysis of the pneumococcal genomes has not been as extensive as that of the lactococcal genomes, there may well be other sites. Again, however, we have not found any intact or defective prophages at any of these sites. Other streptococcal species contain PICIs that are closely related to those in pneumococci (Figure 6b and Supplementary Table S7).

The streptococcal PICIs have been studied in some detail by McShan and co-workers (2012) who have demonstrated that one frequently occupied insertion site in S. pyogenes is between the DNA repair genes, mutS and mutL at ~1.75 Mb in the S. pyogenes genome (Scott et al., 2008). PICI-like elements at this site block transcription of the downstream mutL but excise during exponential growth, restoring transcription and reinsert when stationary phase is reached (Scott et al., 2008). Unlike the typical S. pyogenes PICIs, the PICI-like elements at the mutS/L site appear to have SOS-sensitive repressors and to lack a terS homolog, and therefore, their primary function may be gene regulation rather than transfer. Nguyen and McShan (2014) have suggested that other streptococcal PICIs may also have regulatory roles.

From an evolutionary perspective, as can be seen from the ortholog analysis of SpnCI670-6B (Supplementary Table S9), genes from Streptococcus pyogenes PICIs located between mutS and mutL are in the same list as genes from Streptococcus pyogenes PICIs located elsewhere, suggesting that the streptococcal PICIs belong to a coancestral family that has branched into at least two subfamilies—one involved in regulation, encoding a SOS-inducible repressor, lacking a TerS homolog, and integrating between the DNA repair genes mutS and mutL, and the other in gene transfer, encoding an SOS-insensitive repressor, a TerS homolog, and integrating elsewhere.

In summary, the PICIs within each of these two genera are closely related, suggesting that they are a coherent family that does not contain genetic units of any other type. Very importantly, elements containing additional modules or other complicating segments have not been found in these species—which is why the families are referred to as cohesive.

Accessory genes

Many of the PICIs carry identifiable genes or other elements that do not appear to be involved in the PICI lifecycle (accessory genes—see Supplementary Table S7), of which there seem to be at least four types—(i) transposons, IS sequences and other obviously inserted elements, even including, in at least one case, SpnCI-TCH8431-2, a possibly intact plasmid; (ii) genes involved in helper phage interference—well characterized in S. aureus but as yet defined in only one PICI, EfCIV583; (iii) genes that contribute in possibly important ways to the host organism. In the SaPIs, most of these encode superantigens or other virulence genes (Lindsay et al., 1998; Ubeda et al., 2003; Viana et al., 2010), many of which are carried exclusively by the SaPIs. In the lactococci and streptococci, this class includes genes for diverse metabolic activities and resistances to antibiotics, bacteriocins and bacteriophages; superantigen genes have not been observed; and (iv) phage-related genes that are not standard and seem accidental—including occasional capsid, phage protease and regulatory genes. One phage-related regulatory gene, an ltrC homolog, is of interest since ltrC is an essential phage gene that controls late-phage gene transcription and always occurs just 5′ to terS in prophage genomes (Ferrer et al., 2011; Quiles-Puchalt et al., 2013). However, among the PICIs, the ltrC homolog is always 3′ to terS, is sometimes duplicated, and sometimes occurs without any terS homolog. In the SaPIs, terS is adjacent to the phage interference module, one of whose targets is ltrC (Ram et al., 2014). Perhaps, the PICI-carried ltrC homologs, which are <50% similar their prophage counterparts, are involved in phage interference.

In summary, the PICIs, like other non-essential genomic elements, suffer diverse types of rearrangements, including plasmids, insertions of transposons, IS sequences and so on. Such adventitious insertions occur, of course, in any non-essential region, and are not unique to the PICIs.

Discussion

During the course of this study, it has gradually become apparent that prophages and PICIs have evolved in much more interesting ways than has generally been realized. Remarkably, the genomes of at least the two genera highlighted here, as well as of the staphylococci, contain one or more highly conserved and highly functional lineages of a novel family of mobile genetic elements, the PICIs, which form special archipelagos in the coccal sea. Their special role, which has been defined in S. aureus, is to connect with functional prophages that induce them to reproduce and spread to other individual cells. The prototype of these lineages is the SaPIs, which lead a highly productive existence within the chromosomes of the staphylococci, enabling the phage-mediated spread of superantigens and other important bacterial products (Chen and Novick, 2009; Chen et al., 2015a, b). Additionally, they are of considerable benefit to their bacterial host cells as they interfere with the reproduction of infecting phages and increase the survival of host cells attacked by phages (Ram et al., 2012). The success of this evolutionary strategy is evidenced by the widespread existence of elements of the same type in related species.

As they contain genes that are recognizably phage-related, these elements have been universally annotated as defective prophages. What distinguishes them is that they form cohesive families whose members are closely related both genetically and structurally and are only distantly related to other prophage-derived genetic segments. This is most clearly demonstrated by two of their common features: first, they occupy unique att sites that are not occupied by either intact or defective prophages, and vice versa. Second, many of their genes are conserved within their family but are not detected in other genomes. For the SaPIs, probably the most important of these genes are ppi plus those genes located in operon I, of which only terS is phage-related (Ubeda et al., 2007b). The other genes have key functions in SaPI biology and lack prophage homologs (Novick and Ram, 2015). They were either remodeled from genes of unknown origin or evolved de novo within the SaPIs. Along with terS, they serve to define the SaPI-helper phage interaction and, along with the relatively low frequency of general recombination, have served to maintain the long-term separation between SaPIs and prophages. This separation, applied to the PICIs as well as the SaPIs, is also clearly demonstrated by analyzing the orthology patterns of ORFs encoding HPs. Not only are most of the HPs not detected outside of the family but as it is not known whether they are functional or even whether their genes are translated, their presence, with rare exceptions, as noted, can simply not be explained as acquisition by horizontal transfer—that is, they must have evolved in situ. Consequently, their relatedness serves as an index of the relatedness of the elements carrying them. The same is true of prophages, which also occur as families and also encode many HPs, which follow the same patterns as those of the PICIs.

In summary, the KEGG analyses indicate that the lactococcal and streptococcal PICIs plus EfCIV583 are at most very distantly related to one another or to the SaPIs, yet they share a common genome organization and content. This suggests first that the PICIs in these different genera are probably not coancestral and therefore must have originated independently, after the diversification of the genera, and thus represent a remarkable example of convergent evolution. This result also indicates that the PICI genomic organization has a powerful selective value, as the PICIs are far more common than any other type of phage-related element in the three genera analyzed in detail, staphylococci, streptococci and lactococci. Moreover, it appears that two types of phage-related elements are in the vast majority—the prophages themselves and the SaPIs/PICIs, of which there may be more than a single lineage in some genera. Other types of phage-related elements can be identified, but these are few and far between.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants BIO2011-30503-C02-01, Eranet-pathogenomics PIM2010EPA-00606 and Consolider-Ingenio CSD2009-00006 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICINN), and Grant MR/M003876/1 (Medical Research Council, UK) (to JRP), and by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI022159 (to RPN and JRP).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bolotin A, Wincker P, Mauger S, Jaillon O, Malarme K, Weissenbach J et al. (2001). The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res 11: 731–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpena N, Manning KA, Dokland T, Marina A, Penadés JR. (2016). Convergent evolution of pathogenicity islands in helper cos phage interference. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 371: 20150505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier E, Anton AI, Barry P, Alfonso B, Fang Y, Novick RP. (2004). Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 6076–6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Novick RP. (2009). Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science 323: 139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Carpena N, Quiles-Puchalt N, Ram G, Novick RP, Penadés JR. (2015. a). Intra- and inter-generic transfer of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence genes by cos phages. ISME J 9: 1260–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ram G, Penadés JR, Brown S, Novick RP. (2015. b). Pathogenicity island-directed transfer of unlinked chromosomal virulence genes. Mol Cell 57: 138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopin A, Bolotin A, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD, Chopin M. (2001). Analysis of six prophages in Lactococcus lactis IL1403: different genetic structure of temperate and virulent phage populations. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 644–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverys J-P, Martin B, Håvarstein LS. (2007). Competence-induced fratricide in streptococci. Mol Microbiol 64: 1423–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerkop BA, Clements CV, Rollins D, Rodrigues JLM, Hooper LV. (2012). A composite bacteriophage alters colonization by an intestinal commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 17621–17626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer MD, Quiles-Puchalt N, Harwich MD, Tormo-Más MÁ, Campoy S, Barbé J et al. (2011). RinA controls phage-mediated packaging and transfer of virulence genes in Gram-positive bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 5866–5878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frígols B, Quiles-Puchalt N, Mir-Sanchis I, Donderis J, Elena SF, Buckling A et al. (2015). Virus satellites drive viral evolution and ecology. PLoS Genet 11: e1005609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Aldea M, Washburn BK, Babitzke P, Kushner SR. (1989). New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171: 4617–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay JA, Ruzin A, Ross HF, Kurepina N, Novick RP. (1998). The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 29: 527–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiques E, Ubeda C, Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Lasa I, Novick RP et al. (2007). Role of staphylococcal phage and SaPI integrase in intra- and interspecies SaPI transfer. J Bacteriol 189: 5608–5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos RC, Lapaque N, Rigottier-Gois L, Debarbieux L, Meylheuc T, Gonzalez-Zorn B et al. (2013). Enterococcus faecalis prophage dynamics and contributions to pathogenic traits. PLoS Genet 9: e1003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen SV, McShan WM. (2014). Chromosomal islands of Streptococcus pyogenes and related streptococci: molecular switches for survival and virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4: 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Ram G. (2015). The floating (pathogenicity) island: a genomic dessert. Trends Genet 32: 114–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Christie GE, Penadés JR. (2010). The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan CH, Morris A, Kirby SM, Shingler AH. (1972). Novel method for detection of beta-lactamases by using a chromogenic cephalosporin substrate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1: 283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen IT, Banerjei L, Myers GSA, Nelson KE, Seshadri R, Read TD et al. (2003). Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 299: 2071–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penadés JR, Christie GE. (2015). The phage-inducible chromosomal islands: a family of highly evolved molecular parasites. Annu Rev Virol 2: 181–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiles-Puchalt N, Carpena N, Alonso JC, Novick RP, Marina A, Penadés JR. (2014). Staphylococcal pathogenicity island DNA packaging system involving cos-site packaging and phage-encoded HNH endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 6016–6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiles-Puchalt N, Tormo-Más MÁ, Campoy S, Toledo-Arana A, Monedero V, Lasa I et al. (2013). A super-family of transcriptional activators regulates bacteriophage packaging and lysis in Gram-positive bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 7260–7275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram G, Chen J, Kumar K, Ross HF, Ubeda C, Damle PK et al. (2012). Staphylococcal pathogenicity island interference with helper phage reproduction is a paradigm of molecular parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 16300–16305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram G, Chen J, Ross HF, Novick RP. (2014). Precisely modulated pathogenicity island interference with late phage gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 14536–14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzin A, Lindsay J, Novick RP. (2001). Molecular genetics of SaPI1—a mobile pathogenicity island in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 41: 365–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Nguyen SV, King CJ, Hendrickson C, McShan WM. (2012). Phage-like Streptococcus pyogenes chromosomal islands (SpyCI) and mutator phenotypes: control by growth state and rescue by a SpyCI-encoded promoter. Front Microbiol 3: 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Thompson-Mayberry P, Lahmamsi S, King CJ, McShan WM. (2008). Phage-associated mutator phenotype in group A streptococcus. J Bacteriol 190: 6290–6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straume D, Stamsås GA, Håvarstein LS. (2015). Natural transformation and genome evolution in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Genet Evol 33: 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormo-Más MÁ, Donderis J, García-Caballer M, Alt A, Mir-Sanchis I, Marina A et al. (2013). Phage dUTPases control transfer of virulence genes by a proto-oncogenic G protein-like mechanism. Mol Cell 49: 947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Maiques E, Ubeda C, Selva L, Lasa I et al. (2008). Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island DNA is packaged in particles composed of phage proteins. J Bacteriol 190: 2434–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormo-Más MÁ, Mir I, Shrestha A, Tallent SM, Campoy S, Lasa I et al. (2010). Moonlighting bacteriophage proteins derepress staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. Nature 465: 779–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C, Barry P, Penadés JR, Novick RP. (2007. a). A pathogenicity island replicon in Staphylococcus aureus replicates as an unstable plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14182–14188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C, Maiques E, Barry P, Matthews A, Tormo MA, Lasa I et al. (2008). SaPI mutations affecting replication and transfer and enabling autonomous replication in the absence of helper phage. Mol Microbiol 67: 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C, Maiques E, Knecht E, Lasa I, Novick RP, Penadés JR. (2005). Antibiotic-induced SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence factors in staphylococci. Mol Microbiol 56: 836–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C, Maiques E, Tormo MA, Campoy S, Lasa I, Barbé J et al. (2007. b). SaPI operon I is required for SaPI packaging and is controlled by LexA. Mol Microbiol 65: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C, Tormo MA, Cucarella C, Trotonda P, Foster TJ, Lasa I et al. (2003). Sip, an integrase protein with excision, circularization and integration activities, defines a new family of mobile Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity islands. Mol Microbiol 49: 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana D, Blanco J, Tormo-Más MÁ, Selva L, Guinane CM, Baselga R et al. (2010). Adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus to ruminant and equine hosts involves SaPI-carried variants of von Willebrand factor-binding protein. Mol Microbiol 77: 1583–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.