Abstract

Despite the well-demonstrated efficacy of stem cell (SC) therapy, this approach has a number of key drawbacks. One important concern is the response of pluripotent SCs to treatment with ionizing radiation (IR), given that SCs used in regenerative medicine will eventually be exposed to IR for diagnostic or treatment-associated purposes. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine and compare early IR-induced responses of pluripotent SCs to assess their radioresistance and radiosensitivity. In the present study, 3 cell lines; human embryonic SCs (hESCs), human induced pluripotent SCs (hiPSCs) and primary human dermal fibroblasts (PHDFs); were exposed to IR at doses ranging from 0 to 15 gray (Gy). Double strand breaks (DSBs), and the gene expression of the following DNA repair genes were analyzed: P53; RAD51; BRCA2; PRKDC; and XRCC4. hiPSCs demonstrated greater radioresistance, as fewer DSBs were identified, compared with hESCs. Both pluripotent SC lines exhibited distinct gene expression profiles in the most common DNA repair genes that are involved in homologous recombination, non-homologous end-joining and enhanced DNA damage response following IR exposure. Although hESCs and hiPSCs are equivalent in terms of capacity for pluripotency and differentiation into 3 germ layers, the results of the present study indicate that these 2 types of SCs differ in gene expression following exposure to IR. Consequently, further research is required to determine whether hiPSCs and hESCs are equally safe for application in clinical practice. The present study contributes to a greater understanding of DNA damage response (DDR) mechanisms activated in pluripotent SCs and may aid in the future development of safe SC-based clinical protocols.

Keywords: human induced pluripotent stem cells, human embryonic stem cells, ionizing radiation, double strand breaks, DNA damage, DNA repair

Introduction

Stem cells (SCs) offer a promising approach to regenerative medicine due to an unlimited capacity for self-renewal and differentiation into derivatives of 3 germ layers. For this reason, SCs may be useful as a cell replacement therapy in numerous diseases (1). However, questions have been raised concerning the consequences of SC therapy given that available evidence indicates that certain pluripotent SC lines are genetically unstable, a trait that may lead to ineffective differentiation and, more importantly, uncontrolled proliferation (2). The genomic integrity of SCs is, therefore, an important issue, particularly considering that such cells are expected to be applied in clinical practice in the near future (3,4). Concerns also exist about the response of SCs to treatment with ionizing radiation (IR).

SCs used in regenerative medicine will, inevitably, be exposed to IR (5,6) administered for diagnosis and treatment (7). This is important because undifferentiated cells differ greatly from differentiated cells in numerous aspects, including the course of the cell cycle, metabolic profile, initial level of reactive oxygen species, capacity for DNA repair, apoptosis and the frequency of de novo mutations (8). In addition, hESCs and hiPSCs differ in terms of genotypes and phenotypes (9). All of these factors affect the radiosensitivity of SCs and differentiated cells. SCs possess a unique, short cell cycle, which has an effect on the DNA damage response (DDR) and the DNA repair mechanisms in pluripotent SCs are more efficient compared with those in differentiated cells. Homologous recombination (HR) is the primary repair mechanism for DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). Unrepaired DNA damage in pluripotent SCs directs cells to programmed cell death or differentiation, a response that prevents the accumulation of mutations and contributes to the genetic instability of SC populations (10). Despite the intensive research into SCs in recent years, an understanding of the response of these cells to IR remains limited (11). Furthermore, Long et al demonstrated the importance of early inducible expression of specific genes on the sensitivity of cancer and normal cells to IR (12).

The present study had the following aims: i) To determine the early IR-induced response of hESCs and hiPSCs by measuring phosphorylated H2A histone family member X (γH2AX) and the expression of DNA repair genes; and ii) to compare the early DDR mechanisms in hESCs and hiPSCs. The current study demonstrated that hiPSCs, during the primary response, are more resistant to IR exposure compared with hESCs, exhibiting a response that is similar to that observed in primary human dermal fibroblasts (PHDFs). This indicates that although PHDFs were successfully reprogrammed to hiPSCs, the hiPSCs retain features that are characteristic of the parental differentiated cells. Furthermore, hiPSCs and hESCs promote high activation of different repair genes; breast cancer 2 (BRCA2), X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4 (XRCC4) and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (PRKCD) in hiPSCs, and tumor suppressor protein P53 (P53), RAD51 recombinase (RAD51) and PRKDC in hESCs. The results of the present study contribute to an improved understanding of the changes in the early IR-induced response of pluripotent SCs and consequently provide important information for the safe application of pluripotent SCs in regenerative medicine.

Materials and methods

Culture of hiPSCs

The PHDFs were obtained by full thickness punch biopsy of patients' skin, diagnosed in Greater Poland Cancer Centre (Poznan, Poland), following signing of informed consent. PHDFs were reprogrammed as previously described (13). The pluripotent nature of hiPSCs obtained following reprogramming of PHDFs was confirmed and is presented in Fig. 1. hiPSCs obtained following reprogramming from PHDFs were seeded onto 10 cm Petri dishes in Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) that had been previously coated with inactivated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) as a feeder layer (1×106). Following 24 h preparation of the feeder layer, hiPSCs were seeded at 2×106 in standard hiPSC growth medium containing the following: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) F12 with L-glutamine (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA); 1% non-essential amino acid solution (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA); 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Merck KGaA); and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin (Merck KGaA). Prior to use, the medium was supplemented with fibroblast growth factor 2 (10 ng/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) (13). The culture medium was changed daily. Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

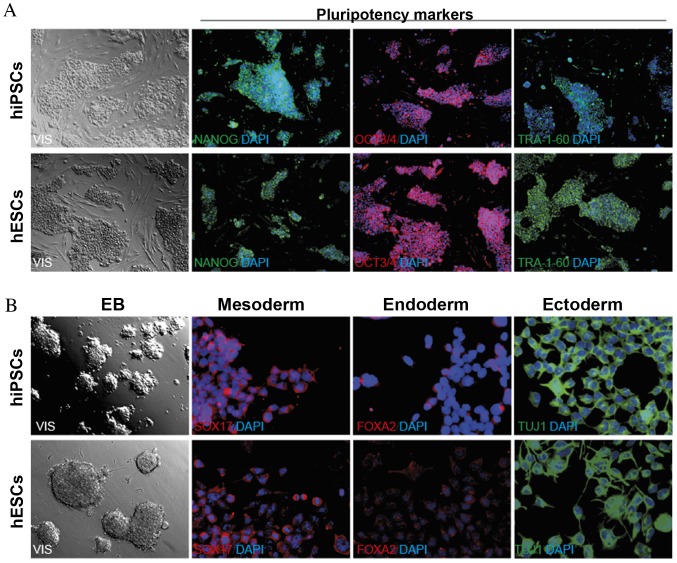

Figure 1.

The pluripotent nature of pluripotent SCs. (A) hiPSCs obtained by the reprogramming process and hESCs indicated the presence of markers associated with pluripotency; NANOG, OCT3/4 and TRA-1-60. (B) Cells demonstrated the ability to form EBs with 3 primary germ layers. SCs, stem cells; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent SCs; hESCs, human embryonic SCs; OCT3/4, octamer binding transcription factor 3/4; TRA-1-60, T cell receptor alpha locus-1-60; EB, embryoid body; SOX17, sex determining region Y-box 17; FOXA2, forkhead box A2.

Culture of hESCs

The culturing process for hESCs (BGV01; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) was almost identical to that described for hiPSCs, except that the standard hESC growth medium consisted of 5% KSR and 15% FBS (Biowest USA, Riverside, MO, USA) instead of 20% KSR (12). The culture medium was changed daily. Cells were cultured at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Culture of PHDFs

Isolated PHDFs were seeded on 10 cm Petri dishes at 2.5×106 in human fibroblast growth medium that contained the following: DMEM-High Glucose (Biowest USA); 10% FBS (Biowest USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Merck KGaA). The medium was changed every 2–3 days. Cells were cultured at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Embryoid body (EB) formation and immunofluorescence staining

To verify the ability of the hiPSCs to differentiate into three primary germ layers, EB formation and immunofluorescence staining (NANOG, OCT3/4, TRA-1-60 and SOX17, FOXA2, TUJ1) was performed (Fig. 1) (1).

Irradiation

Confluent hiPSCS, hESCs and PHDFs were irradiated at room temperature in the aforementioned growth medium, using a Clinac 2300C/D linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) at the following dose levels: Low dose (0, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 Gy); and high dose (2, 5, 10 and 15 Gy). Immediately following irradiation, cells were incubated for 1 h in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The selection of 1 h as the first time-point following treatment with a DNA-damaging agent, to ensure the most visible changes, was selected based on data from the existing literature (14–17) (Fig. 2).

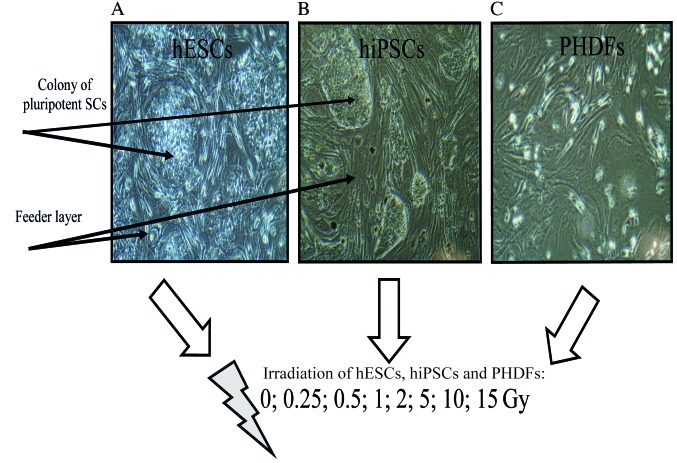

Figure 2.

Culturing pluripotent SCs and PHDFs. (A) hESCs and (B) hiPSCs form colonies in co-culture with murine embryonic fibroblasts. (C) PHDFs grow in a traditional monolayer culture. SCs, stem cells; PHDFs, primary human dermal fibroblasts; hESCs, human embryonic SCs; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent SCs; Gy, gray.

Flow cytometry analysis of γH2AX

Cells (hESCs, hiPSCs and PHDFs) were stained for γH2AX with the Alexa Fluor® 647 Mouse H2AX (pS139) antibody (catalog no. 560447, BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, ~5×105 IR-treated and untreated cells were collected. Fixation and permeabilization were performed simultaneously for all cells using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Permeabilization solution for 20 min (BD Biosciences) at room temperature. Fixed cells were rinsed and subsequently stained with H2AX antibody (5 µl/test) in 20 µl BD Perm/Wash™ buffer for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml staining buffer and analyzed with a flow cytometer (BD Accuri™ C6) using a 675/25 FL4 filter within 1 h. For isotype control, the Alexa Fluor® 647 Mouse IgG1 κ Isotype Control (catalog no. 557714; 5 µl/test; BD Biosciences) was used. Fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units was plotted in histograms and contour plots, and the mean fluorescence intensity was calculated. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo v10; LLC, Ashland, OR, USA).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRI Reagent® (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA (1 µg per 20 µl reaction volume) was reverse-transcribed using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol (25°C for 5 min, 42°C for 30 min, 85°C for 5 min). Amplification products of individual gene transcripts were detected via fluorescent probes (Universal Probe Library; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) and Probe Master (LightCycler 480 Probes Master; Roche Diagnostics). The appropriate primers (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) were designed with Universal Probe Library software (Roche Diagnostics), with sequences presented in Table I.

Table I.

Forward and reverse primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer sequence | Probe |

|---|---|---|

| P53 | Forward: ctttccacgacggtgaca | 71 |

| Reverse: tcctccatggcagtgacc | ||

| RAD51 | Forward: atcactaatcaggtggtagctcaa | 58 |

| Reverse: cccctcttcctttcctcaga | ||

| BRCA2 | Forward: cctgatgcctgtacacctctt | 45 |

| Reverse: gcaggccgagtactgttagc | ||

| XRCC4 | Forward: tggtgaactgagaaaagcattg | 68 |

| Reverse: tgaaggaaccaagtctgaatga | ||

| PRKDC | Forward: agaggctgggagcatcact | 31 |

P53, tumor suppressor protein P53; RAD51, RAD51 recombinase; BRCA2, breast cancer 2; XRCC4, X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4; PRKDC, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit.

The reaction conditions for all amplicons were as follows: initially 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles at 94°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 15 sec and 72°C for 1 sec. All reactions were performed in the presence of 3.2 mM MgCl2. cDNA samples (2.5 µl for total volume of 10 µl) were analyzed for genes of interest and for the reference gene GAPDH. The average cycle threshold (Cq) value was used to calculate the mRNA expression levels of genes of interest, relative to the expression level of the reference gene-GAPDH. This was conducted via use of the comparative cycle time (ΔCq) method. Furthermore, the Cq method was applied to calculate the relative amount of target gene expression and the expression level of each target gene was normalized to GAPDH (05–190-541-001; Roche Diagnostics) expression using-2ΔΔCq (18). The reaction was carried out in triplicate for the gene of interest.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between the study groups and controls were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by post-hoc analysis using Tukey's multiple comparison test with a single pooled variance. Comparisons between the study groups and controls were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Obtaining hiPSCs from PHDFs

The microscopic evaluation of hiPSCs indicated that hiPSC colonies composed of homogenous cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, demonstrated characteristics of pluripotent SCs. The expression of pluripotency markers (NANOG, OCT3/4, TRA-1-60) in hiPSCs was confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis. To prove the ability of hiPSCs to differentiate into three primary germ layers (meso-, endo- and ectoderm), spontaneous differentiation via EB formation was performed. In the two-week EB formation, the presence of specific markers: SOX17, FOXA2 and TUJ1 was assessed by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1).

The irradiation of cells

In order to investigate and compare the early responses of pluripotent SCs, the analyzed cells (feeder- dependent hESCs and hiPSCs; PHDFs) were irradiated at the following range of doses: 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 15 Gy (Fig. 2).

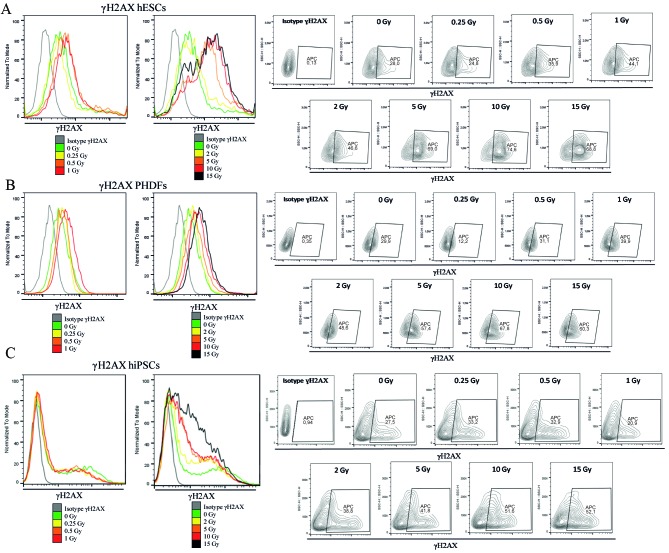

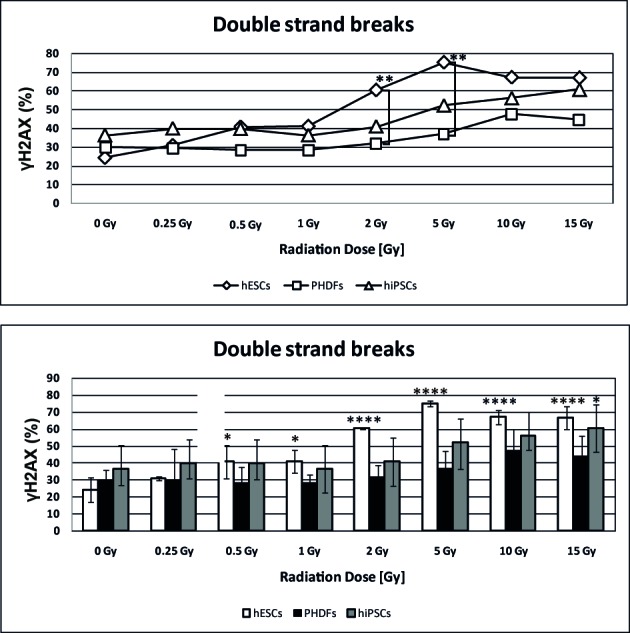

Analysis of DSBs in irradiated cells

DSBs, as a percentage of γH2AX, were more common in SCs compared with PHDFs. The number of DSBs observed in hESCs that were irradiated at 2 and 5 Gy was significantly higher compared with the number of DSBs in PHDFs (P<0.01; Fig. 3). Both SC cell lines exhibited, statistically significant in the case of hESCs particularly above 2 Gy (P<0.0001), increases in DSBs at high doses of γ-radiation compared with the control at 0 GyIrradiated PHDFs exhibited a noticeable but not statistically significant increase in DSBs (Fig. 3). Representative histograms and contour plots for each cell line are presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 3.

Amount of DNA DSBs in irradiated cells. Compared with hESCs, hiPSCs demonstrated high radioresistance that was similar to that exhibited by PHDFs, which resulted in a low level of DSBs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; and ****P<0.0001 vs. cells at 0 Gy. Significant differences between different cell lines at the same radiation doses are indicated by brackets. DSBs, double strand breaks; SCs, stem cells; hESCs, human embryonic SCs; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent SCs; PHDFs, primary human dermal fibroblasts; γH2AX, phosphorylated H2A histone family member X; Gy, gray.

Figure 4.

Visualization of DNA DSBs as γH2AX in irradiated cells. Representative contour plots and histograms for (A) hESCs, (B) PHDFs and (C) hiPSCs demonstrate the changes in the level of DSBs following ionizing radiation for each of the 3 cell lines. DSBs, double strand breaks; γH2AX, phosphorylated H2A histone family member X; SCs, stem cells; hESCs, human embryonic SCs; PHDFs, primary human dermal fibroblasts; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent SCs; Gy, gray; APC, allophycocyanin.

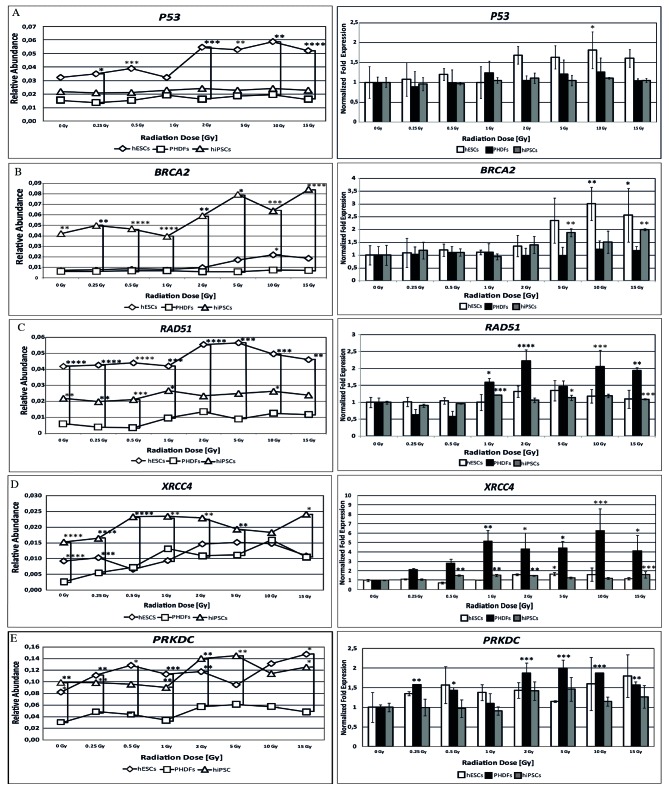

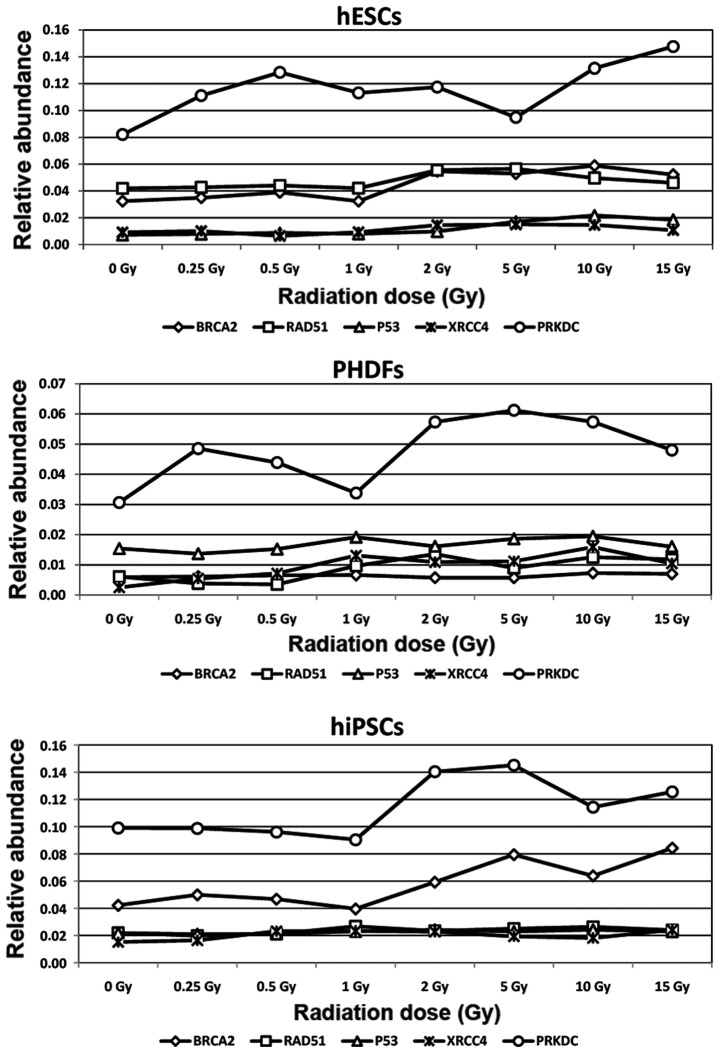

P53 expression

Based on relative abundance and normalized fold expression (Fig. 5A), P53 expression was highest in hESCs. However, P53 expression was only significantly different compared with 0 Gy at 10 Gy in hESCs (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Expression of activated genes involved in DNA repair in irradiated cells. Expression of (A) P53 (B) BRCA2 and (C) RAD51 genes involved in homologous recombination method of DNA repair. Expression of (D) XRCC4 and (E) PRKDC genes involved in the non-homologous end joining method of DNA repair. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; and ****P<0.0001 vs. cells at 0 Gy. Significant differences between different cell lines at the same radiation doses are indicated by brackets. P53, tumor suppressor protein P53; BRCA2, breast cancer 2; RAD51, RAD51 recombinase; XRCC4, X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4; PRKDC, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit; SCs, stem cells; hESCs, human embryonic SCs; PHDFs, primary human dermal fibroblasts; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent SCs; Gy, gray.

BRCA2 expression

Of the 3 cell lines, the present study demonstrated that the relative abundance of BRCA2 gene expression was highest in hiPSCs. However, an increase in the relative abundance of BRCA2 transcript was also observed in hESCs. Normalized fold expression of the BRCA2 gene was statistically significant at certain radiation doses in hESCs and hiPSCs; at 10 (P<0.01) and 15 Gy (P<0.05) in hESCs the expression was double that observed in cells at 0 Gy, and significant differences were observed in hiPSCs at 5 and 15 Gy (P<0.01; Fig. 5B).

RAD51 expression

The relative abundance of RAD51 mRNA differed among cell lines; the highest level was observed in hESCs, followed by hiPSCs and PHDFs. Although PHDFs exhibited the lowest level of relative abundance of the RAD51 transcript, they also demonstrated the largest increase in RAD51 normalized fold expression, significantly higher compared with SC lines, reaching a two-fold increase at 2 Gy compared with 0 Gy (P<0.0001; Fig. 5C).

XRCC4 expression

hiPSCs had the highest relative abundance of XRCC4 mRNA. By contrast, lower levels were observed in hESCs and PHDFs. However, based on normalized fold expression, XRCC4 expression was highest in PHDFs; 5 times higher at 1 Gy compared with 0 Gy (P<0.01). XRCC4 expression was also high in hiPSCs, with significantly higher levels compared with controls at certain doses (P<0.01; Fig. 5D).

PRKDC expression

Both SC lines exhibited similar relative abundance of PRKDC gene expression, which was significantly higher compared with differentiated cells (P<0.05). Compared with cells at 0 Gy in each cell line, the relative PRKDC expression was highest in PHDFs, with statistically significant increases between 2 and 15 Gy doses (P<0.01; Fig. 5E).

Gene expression profile of individual cell lines

Due to the relative abundance of the aforementioned gene transcripts, the gene expression profiles for each cell line was distinct. hESCs had the highest expression of the PRKCD gene, exhibiting the highest initial and final relative abundance. RAD51 and BRCA2 expression were also visible in this cell line. In hESCs, the expression of XRCC4 and P53 was notably lower compared with RAD51, BRCA2 and particularly PRKCD expression (Fig. 6). In hiPSCs, the most prominent gene was PRKDC. Expression of the BRCA2 gene in this cell line was lower but observable. The lowest level of gene expression was observed for RAD51, P53 and XRCC4 genes (Fig 6). In PHDFs, the relative abundance of the PRKDC transcript was high compared with BRCA2, RAD51, P53 and XRCC4 genes (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Gene expression profile of activated genes in cell lines following ionizing radiation treatment. hESCs, PHDFs and hiPSCs were characterized by distinct DNA repair gene expression profiles, indicating the existence of cell line-dependent DNA damage response mechanisms. SCs, stem cells; hESCs, human embryonic SCs; PHDFs, primary human dermal fibroblasts; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent SCs; Gy, gray; BRCA2, breast cancer 2; RAD51, RAD51 recombinase; P53, tumor suppressor protein P53; XRCC4, X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4; PRKDC, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit.

Discussion

Human pluripotent stem cells present a promising approach for numerous disorders. However, pluripotent SCs used in regenerative medicine will inevitably be exposed to IR for diagnostic purposes and/or radiotherapy treatment. For this reason, it is important to broaden our understanding of the radioresistance properties in these cells. Firstly, hiPSCs were generated from PHDFs, with pluripotent nature and capacity to differentiate into three primary germ layers, verified. The present study evaluated and compared the early response of hESCs and hiPSCs to IR administered at doses ranging from low to high (0–15 Gy). The primary aim of this study was to determine DSB formation and the activation of the principal DNA repair genes following IR treatment. Notably, the results of the current study demonstrated that hiPSCs, in the initial response, are less sensitive to IR compared with hESCs. Furthermore, hiPSCs have a different expression profile of DNA damage response associated genes following IR, which has an impact on radioresistance and makes them less resistant to radiation compared with hESCs.

The present study identified that DSB formation in hiPSCs is similar to PHDFs, but differs compared with hESCs. Mouse and human pluripotent SCs exhibit important differences that should be considered in any analysis. The majority of previous studies have been conducted with mouse ESCs (mESCs) (19–21). However, these results cannot be directly applied to human cells. Although mESCs and hESCs are well-understood, little is known about miPSCs, and information about hiPSCs is limited. mESCs have increased genetic stability compared with differentiated cells because, in response to DSBs, the recruitment of the stemness factor spalt like transcription factor 4 is required to activate the critical ataxia telaniectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent cellular pathway (19). In somatic cells, cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), the major regulator of the G1/S transition, is impaired by cell division cycle 25A (CDC25A) phosphatase, which initiates G1 checkpoint. In mESCs, CDK2 is protected from regulation by nuclear CDC25A, indicating that high CDK2 activity may be responsible for the instant escape of mESCs from the G1 phase and the following G1 checkpoint following DNA damage (20). Compared with hESCs, mESCs have a higher level of strand breaks and endogenous repair foci, potentially due to global chromatin decondensation rather than pre-existing DNA damage, indicating differences in chromatin organization between mESCs and hESCs. The differentiation process leads to a reduction in histone acetylation, γH2AX foci formation and sensitivity of replicating cell chromatin (21).

Sokolov et al (22) provided evidence that doses of up to 1 Gy of IR did not influence the pluripotency of hESCs. They demonstrated that the surviving hESCs maintained a high expression of genes responsible for pluripotency, including octamer binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), NANOG, sex determining region Y-box 2, stage-specific embryonic antigen 4, telomerase reverse transcriptase and T cell receptor alpha locus (TRA-1-60 and TRA1-81). Momčilovic et al (23) first reported that, following 2 Gy of γ-radiation, hESCs temporarily arrested the cell cycle in the G2 stage, however, not in the G1 stage. For complete induction of G2 arrest, ATM phosphorylation and localization at the sites of DNA DSBs is required. It was also observed that, ~16 h following irradiation, hESCs restarted the cell cycle with a high proportion of aberrant mitotic figures. Filion et al (24) also demonstrated that hESCs, in contrast with somatic cells, lack a G1 checkpoint. In response to IR, hESCs rapidly induced phosphorylation of H2AX and P53, and stopped dividing in the G2 phase. This phenomenon is enhanced by the activation of ATM, checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) and survivin pathways without cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (P21) recruitment. However, strong activation of survivin does not guarantee increased cell survival; the opposite occurs and the hESCs undergo apoptosis, thus, ensuring the genomic integrity of the surviving hESCs. Neganova et al (25) reported that downregulation of CDK2 in hESCs leads to G1/S checkpoint activation via the ATM-CHK2-P53-P21 pathway. Decreased production of CDK2 also triggers DSBs and high levels of apoptosis.

miPSCs are less sensitive to low and high dose IR compared with mouse hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Hayashi et al (26) reported that irradiated miPSCs retained the ability to form embryoid bodies (EBs) with 3 germ layers. The diameter of formed EBs decreased in a radiation dose-dependent manner. However, the further/more comprehensive response of iPSCs to IR was not evaluated. However, the results of that study indicated that different types of human pluripotent SCs cannot be treated equally, a result that was confirmed in the present study; hESCs exhibited the highest radiosensitivity to all IR doses. This indicates that hESCs possess a high DNA repair capacity, however also undergo mass cell death when damaged, thus avoiding genetic instability in irradiated cell populations. Consistent with previous studies (27), the present study demonstrated that hiPSCs exhibit a level of radioresistance, which results in the low formation of γH2AX (Figs. 3 and 4). This is notable given that hiPSCs are difficult to maintain in culture and readily undergo apoptosis. Spontaneous SC differentiation or dedifferentiation were ruled out as pluripotency of these cells was maintained at a high and stable level throughout the experiment. The results indicate that hiPSCs may partially preserve a transcriptional memory of their parent somatic cells (PHDFs).

The current study demonstrated that, following IR, P53 was more highly expressed by hESCs compared with hiPSCs and PHDFs. Depending on stress severity, nuclear P53 transactivates proapoptotic or antioxidant genes, while cytoplasmic P53 has an important role in inducing mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis (28). In mESCs, P53 is scarcely phosphorylated in response to IR, as evidenced by the low expression of the P53-target P21 gene. However, despite a dysfunctional P21 pathway, mESCs are capable of inducing ATM and γH2AX foci, which is indispensable for the activation of DDR (29). P53 regulates pro- and anti-differentiation pathways in mESCs (30), and in mESCs P53 has an anti-differentiation role through direct regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway. In mESCs, anti-proliferative P53 is localized primarily in the cytoplasm, thus, preventing the cell from activating its target genes. In response to IR, P53 accumulates in the cell nucleus, where induction of P53 target genes subsequently occurs. Target genes that are induced include mouse double minute 2 homolog, P21, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1, and P53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis; inhibition of NANOG is also important (31,32). Previous studies have demonstrated that mESCs and hESCs possess a nonfunctional P53-P21 axis of the G1/S checkpoint pathway, which is regulated by specific DDR mechanisms. Dolezalova et al (33) demonstrated that, although hESCs have the ability to stabilize and activate the P53 protein, these cells do not produce the P21 protein even in the presence of P21 mRNA. This mechanism is regulated by the miRNA family, specifically miR-302, which post-transcriptionally regulates the expression of the P21 protein. Solozoba and Blattner (34) demonstrated that P53 is more abundant in mESCs compared with somatic cells, primarily due to the enhanced stability of P53 RNA and protein de novo synthesis. During the differentiation process, the level of P53 mRNA decreases and, consequently, so does P53 protein synthesis. Furthermore, in differentiated ESCs, miR-125a and miR-125b expression, well established repressors of p53, was increased.

Unlike mESCs, hESCs are difficult to maintain in culture as they readily undergo spontaneous differentiation and apoptosis. In apoptotic hESCs, P53 accumulates and is subsequently followed by initiation of the apoptotic mitochondrial pathway. Although P53 accumulation in mESCs and hESCs was demonstrated by Qin et al (35), activation of the transcription of P53 target genes was significantly lower in hESCs compared with mESCs. Lower P53 levels are associated with the promotion of cell survival and reduced spontaneous differentiation. The first investigation of hESC genome-wide transcriptional changes following IR was performed by Wilson et al (36), which demonstrated that although some genes involved in developmental pathways were altered with doses up to 4 Gy of IR, expression of pluripotency genes remained unchanged. Furthermore, surviving cells retained the capacity to recover and form teratomas, the definitive test of pluripotency. In hESCs, the majority of P53-binding sites are unique to each pluripotency- and differentiation-dependent state and define stimulus-specific P53 responses. During early differentiation, activated P53 targets influence core pluripotency factors, including OCT4 and NANOG in chromatin enriched with H3K27me3 and H3K4me3. When DNA damage occurs, P53 specifically binds to genes that are associated with cell migration and motility (37). Sokolov and Neumann (38) and Sokolov et al (39) investigated the effects of low doses (up to 0.1 Gy) of IR exposure on stress-responsive gene expression in hESCs. The results indicated that this type of gene expression in hESCs is temporal and cell line dependent, however, there was no linear dose-dependent association within the lowest doses of IR (38,39).

Knockout of P53 in reprogrammed human cells leads to genomic instability. Transient suppression of P53 facilitates reprogramming due to an increased number of iPSC colonies with high expression of pluripotency genes, however, apoptotic and DNA damage mechanisms are not affected, thus, resulting in the generation of a stable iPSC cell line (40). Notably, in hiPSCs, genome surveillance is achieved via hypersensitivity to apoptosis and a low accumulation of DNA lesions (21), this was also confirmed in the present study. In hiPSCs, apoptosis is mediated by constitutive P53 expression and upregulation of pro-apoptotic P53 target genes belonging to the BCL-2 family. Although apoptosis sensitivity in hiPSCs is elevated, DNA lesions following genotoxic treatment have been demonstrated to be less common in hiPSCs compared with PHDFs, partially due to increased expression of genes that code for antioxidant proteins (41). Momcilovic et al (42) performed a comprehensive investigation to assess the radiosensitivity of hESCs and hiPSCs, which confirmed that both irradiated pluripotent SC lines exhibited robust expression of pluripotency markers. Subsequently, it was demonstrated that the activation level of ATM and its target proteins in hiPSCs are similar to results obtained in hESCs. Similar to hESCs, hiPSC differentiation was arrested in the G2 phase, confirming that the reprogramming process leads to loss of G1/S arrest, thus, preserving cells from differentiation. Finally, it was demonstrated that hESCs and hiPSCs repair DNA lesions predominantly via HR. However, in addition to elevated expression of genes engaged in HR, hESCs and hiPSCs also exhibited increased expression of genes involved in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which is the opposite to what occurs in mESCs. The present study partially expands and updates the results reported by Momcilovic et al (42) as a wider range of IR doses (0–15 Gy) were employed. The present study demonstrated that, although P53 was highly expressed by hESCs, its expression was significantly lower in hiPSCs and PHDFs. These results are consistent with data from hESCs, which exhibited the largest number of DSBs (Fig. 5A). This is consistent with previously published data, indicating that P53 is highly activated in response to DNA damage. This phenomenon may also reflect a more effective pluripotency state of hESCs compared with hiPSCs, demonstrating the important role of P53 in maintaining pluripotency.

Homology-dependent and independent DNA repair pathways are involved in the protection of cells against IR-induced DNA damage and consequent chromosomal changes (43). For mESCs, the homology-dependent mechanism is particularly important. Unlike MEFs, ESCs have the capacity to repair endogenous DNA damage without the activation of NHEJ. Tichy et al (44) demonstrated that mESCs translate RAD51 mRNA, a major component of HR, with higher efficacy compared with MEFs. Excessive RAD51 expression is likely to be a major mechanism by which cells respond to DSBs or delay the replication fork without affecting cell proliferation rate. Sioftanos et al (45) demonstrated that, in mESCs, BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygosity is associated with the formation of low numbers of RAD51 foci per nucleus, however, the general radiosensitivity of these cells was not altered. However, the authors, do not rule out the potential emergence of late effects such as enhanced mutagenesis.

Notably, expression levels of genes involved in the NHEJ mechanism vary substantially between mESCs and hESCs. Ku70/80 is expressed at higher levels in mESCs compared with hESCs and somatic cells. However, mESCs are also characterized by a deficiency in PRKDC. Therefore, following IR, mESCs and hESCs differ in the extent of DNA damage response; hESCs rejoin breaks rapidly, via the NHEJ mechanism, thus, expressing a high level of PRKDC, whereas mESCs favor HR for DSB repair (46). The pathways that maintain genetic stability exhibit enhanced activity in hESCs compared with PHDFs and formed EBs. In response to DNA-damaging agents, which includes IR (47), the mRNA levels of certain DNA repair genes are elevated, including BRCA1, xeroderma pigmentosum type B, XRCC4 and Ku80. However, the mRNA levels of xeroderma pigmentosum type A, xeroderma pigmentosum type C and xeroderma pigmentosum type G are notably decreased. Felgentreff et al (48) reported that the NHEJ pathway has a critical role in somatic cell reprogramming and in maintaining the genomic stability of hiPSCs. Particularly, it was demonstrated that DNA ligase 4 and PRKDC are required for the correct functioning of the NHEJ mechanism and high reprogramming efficiency (48). The results of the present study confirm previous reports that indicated that pluripotent SCs more effectively activate certain DNA repair genes (RAD51, BRCA2, XRCC4 and PRKDC) following IR compared with PHDFs. hiPSCs are characterized by high BRCA2, XRCC4 and PRKCD gene expression, whereas hESCs exhibit higher expression of RAD51 and PRKDC (Fig. 5). Although HR is characteristic for pluripotent SCs as a major DSB repair mechanism, SCs exhibit a capacity to induce components of NHEJ. Differences between cell lines in terms of expression of DNA repair genes also resulted in a distinct gene expression profile for each line (Fig 6). The initial response of cells changed in a dose-dependent manner, however, in the majority of cases, significant changes were not observed until 2 Gy, indicating that this dose may be the threshold dose for initiating DDR. The results presented in this study indicate that, although pluripotent SCs possess similar features, including self-renewal and a capacity to differentiate into derivatives of 3 germ layers, they also possess highly dissimilar radiosensitivity and, consequently, genome integrity machinery.

In conclusion, the present study has described the early IR-induced response of hESCs, hiPSCs and PHDFs. Pluripotent SCs form an increased number of DSBs following IR treatment compared with PHDFs. Notably, hESCs are extremely sensitive to IR, which was indicated by a high number of DSBs. The level of DSB formation in hiPSCs in response to IR resembles that observed in PHDFs rather than in hESCs. The accumulation of DSBs results in a distinct gene expression profile of activated DNA repair genes in each cell line. Irradiated pluripotent SCs readily activate genes belonging to HR and NHEJ, indicating that they possess effective DNA repair mechanisms, in contrast to the genes that are activated by fully differentiated cells. The present study contributes to an improved understanding of the induction of DNA damage repair mechanisms in human pluripotent SCs in response to IR. The results of the current study may contribute to safer clinical application of pluripotent SCs in patients with a high risk of developing cancer. In addition, the present study emphasizes the questions surrounding the reprogramming process in the evaluation of activated DDR mechanisms. However, given the preliminary nature of the current study, more research is required to reach definitive conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the present study was supported by the National Science Centre (grant no. 2012/07/E/NZ3/01819) and by The Greater Cancer Centre (grant no. 19/02/2016/PRB/WCO/010). The authors would like to thank Bradley Londres for his assistance in editing this study.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SCs

stem cells

- hESCs

human embryonic stem cells

- hiPSCs

human induced pluripotent stem cells

- PHDFs

primary human dermal fibroblasts

- IR

ionizing radiation

- DSBs

double strand breaks

- P53

tumor suppressor protein P53

- RAD51

RAD51 recombinase

- BRCA2

breast cancer 2

- XRCC4

X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4

- PRKDC

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit

References

- 1.Suchorska WM, Lach MS, Richter M, Kaczmarczyk J, Trzeciak T. Bioimaging: An useful tool to monitor differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into chondrocytes. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:1845–1859. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1443-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustyniak E, Trzeciak T, Richter M, Kaczmarczyk J, Suchorska W. The role of growth factors in stem cell-directed chondrogenesis: A real hope for damaged cartilage regeneration. Int Orthop. 2015;39:995–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen MF, Lin CT, Chen WC, Yang CT, Chen CC, Liao SK, Liu JM, Lu CH, Lee KD. The sensitivity of human mesenchymal stem cells to ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin YW, Na YJ, Lee YJ, An S, Lee JE, Jung M, Kim H, Nam SY, Kim CS, Yang KH, et al. Comprehensive analysis of time- and dose-dependent patterns of gene expression in a human mesenchymal stem cell line exposed to low-dose ionizing radiation. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaman MH. The role of engineering aproaches in analysis cancer invasion and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:596–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Magalhães JP. How ageing processess influence cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:357–365. doi: 10.1038/nrc3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokolov MV, Neumann RD. Human embryonic stem cell responses to ionizing radiation exposures: Current state of knowledge and future challenges. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:579104. doi: 10.1155/2012/579104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suchorska WM, Augustyniak E, Łukjanow M. Genetic stability of pluripotent stem cells during anti-cancer therapies. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11:695–702. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Beard C, Gao Q, Bell GW, Cook EG, Hargus G, Blak A, Cooper O, Mitalipova M. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factor. Cell. 2009;136:964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung H, Weinstock DM. Repair at single targeted DNA double-strand breaks in pluripotent and differentiated human cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocha CR, Lerner LK, Okamoto OK. The role of DNA repair in the pluripotency and differentiation of human stem cells. Mutat Res. 2013;752:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long XH, Zhao ZQ, He XP, Wang HP, Xu QZ, An J, Bai B, Sui JL, Zhou PK. Dose-dependent expression changes of early response genes to ionizing radiation in human lymphoblastoid cells. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wróblewska J. A new method to generate human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) and the role of the protein KAP1 in epigenetic regulation of self-renewal. http://www.wbc.poznan.pl/Content/373798/index.pdf. Doctoral dissertation. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banáth JP, MacPhail SH, Olive PL. Radiation sensitivity, H2AX phosphorylation and kinetics of repair of DNA strand breaks in irradiated cervical cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7144–7149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An J, Huang YC, Xu QZ, Zhou LJ, Shang ZF, Huang B, Wang Y, Liu XD, Wu DC, Zhou PK. DNA-PKcs plays a dominant role in the regulation of H2AX phosphorylation in response to DNA damage and cell cycle progression. BMC Mol Biol. 2010;11:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scarpanto E, Castagna S, Aliotta R, Azzarà A, Ghetti F, Filomeni E, Giovannini C, Pirillo C, Testi S, Lombardi S, Tomei A. Kinetics of nuclear phosphorylation (γ-H2AX) in human lymphocytes treated in vitro with UVB, bleomycin and mitomycin C. Mutagenesis. 2013;28:465–473. doi: 10.1093/mutage/get024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mah LJ, Vasireddy RS, Tang MM, Georgiadis GT, El-Osta A, Karagiannis TC. Quantification of gammaH2AX foci in response to ionising radiation. J Vis Exp. 2010;pii:1957. doi: 10.3791/1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)). Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong J, Todorova D, Su NY, Kim J, Lee PJ, Shen Z, Briggs SP, Xu Y. Stemness factor Sall4 is required for DNA damage response in embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:513–520. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koledova Z, Kafkova LR, Krämer A, Divoky V. DNA damage-induced degradation of Cdc25A does not lead to inhibition of Cdk2 activity in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:450–461. doi: 10.1002/stem.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banáth JP, Bañuelos CA, Klokov D, MacPhail SM, Lansdorp PM, Olive PL. Explanation for excessive DNA single-strand breaks and endogenous repair foci in pluripotent mouse embryonic stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1505–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokolov MV, Panyutin IV, Onyshchenko MI, Panyutin IG, Neumann RD. Expression of pluripotency-associated genes in the surviving fraction of cultured human embryonic stem cells is not significantly affected by ionizing radiation. Gene. 2010;455:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Momčilovic O, Choi S, Varum S, Bakkenist C, Schatten G, Navara C. Ionizing radiation induces ataxia telangiectasia mutated-dependent checkpoint signaling and G(2) but not G(1) cell cycle arrest in pluripotent human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1822–1835. doi: 10.1002/stem.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filion TM, Qiao M, Ghule PN, Mandeville M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Altieri DC, Stein GS. Survival responses of human embryonic stem cells to DNA damage. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:586–592. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neganova I, Vilella F, Atkinson SP, Lloret M, Passos JF, von Zglinicki T, O'Connor JE, Burks D, Jones R, Armstrong L, Lako M. An important role for CDK2 in G1 to S checkpoint activation and DNA damage response in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:651–659. doi: 10.1002/stem.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi N, Monzen S, Ito K, Fujioka T, Nakamura Y, Kashiwakura I. Effects of ionizing radiation on proliferation and differentiation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. J Radiat Res. 2012;53:195–201. doi: 10.1269/jrr.11138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagaria PK, Robert C, Park TS, Huo JS, Zambidis ET, Rassool FV. High-fidelity reprogrammed human IPSCs have a high efficacy of DNA repair and resemble hESCs in their MYC transcriptional signature. Stem Cell Int. 2016;2016:3826249. doi: 10.1155/2016/3826249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han MK, Song EK, Guo Y, Ou X, Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. SIRT1 regulates apoptosis and Nanog expression in mouse embryonic stem cells by controlling p53 subcellular localization. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuykin IA, Lianguzova MS, Pospelova TV, Pospelov VA. Activation of DNA damage response signaling in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2922–2928. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KH, Li M, Michalowski AM, Zhang X, Liao H, Chen L, Xu Y, Wu X, Huang J. A genomwide study identifies the Wnt signaling pathway as a major target of p53 in murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:69–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909734107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdelalim EM, Tooyama I. Knockdown of p53 suppressess Nanog expression in embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solozobova V, Rolletschek A, Blattner C. Nuclear accumulation and activation of p53 in embryonic stem cells after DNA damage. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolezalova D, Mraz M, Barta T, Plevova K, Vinarsky V, Holubcova Z, Jaros J, Dvorak P, Pospisilova S, Hampl A. MicroRNAs regulate p21(Waf1/Cip1) protein expression and the DNA damage response in human ebryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1362–1372. doi: 10.1002/stem.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solozobova V, Blattner C. Regulation of p53 in embryonic stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2434–2446. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin H, Yu T, Qing T, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Cai J, Li J, Song Z, Qu X, Zhou P, et al. Regulation of apoptosis and differentiation by p53 in human embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5842–5852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson KD, Sun H, Huang M, Zhang WY, Lee AS, Li Z, Wang SX, Wu JC. Effects of ionizing radiation on self-renewal and pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5539–5558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akdemir KC, Jain AK, Allton K, Aronow B, Xu X, Cooney AJ, Li W, Barton MC. Genome-wide profiling reveals stimulus-specific functions of p53 during differentiation and DNA damage of human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acid Research. 2014;42:205–223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sokolov M, Neumann R. Effects of low doses of ionizing radiation exposures on stress-responsive gene expression in human embryonic stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:588–604. doi: 10.3390/ijms15010588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sokolov M, Nguyen V, Neumann R. Comparative analysis of whole-genome gene expression changes in cultured human embryonic stem cells in response to low, clinical diagnostic relevant and high doses of ionizing radiation exposure. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:14737–14748. doi: 10.3390/ijms160714737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen MA, Holst B, Tümer Z, Johnsen MG, Zhou S, Stummann TC, Hyttel P, Clausen C. Transient p53 suppression increases reprogramming of human fibroblasts without affecting apoptosis and DNA damage. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dannenmann B, Lehle S, Hildebrand DG, Kübler A, Grondona P, Schmid V, Holzer K, Fröschl M, Essmann F, Rothfuss O, Schulze-Osthoff K. High glutathione and glutathione preoxidase-2 levels mediate cell-type-specific DNA damage protection in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:886–898. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Momcilovic O, Knobloch L, Fornsaqlio J, Varum S, Easley C, Schatten G. DNA damage responses in human induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffin C, Waard Hd, Deans B, Thacker J. The involvement of key DNA repair pathways in the formation of chromosome rearrangements in embryonic stem cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tichy ED, Pillai R, Deng L, Tischfield JA, Hexley P, Babcock GF, Stambrook PJ. The abundance of Rad51 protein in mouse embryonic stem cells is regulated at multiple levels. Stem Cell Res. 2012;9:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sioftanos G, Ismail A, Föhse L, Shanley S, Worku M, Short SC. BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygosity in embryonic stem cells reduces radiation-induced Rad51 focus formation but is not associated with radiosensitivity. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:1095–1105. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2010.501836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bañuelos CA, Banáth JP, MacPhail SH, Zhao J, Eaves CA, O'Connor MD, Lansdorp PM, Olive PL. Mouse but not human embryonic stem cells are deficient in rejoining of ionizing radiation- induced DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1471–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maynard S, Swistowska AM, Lee JW, Liu Y, Liu ST, Da Cruz AB, Rao M, de S, ouza-Pinto NC, Zeng X, Bohr VA. Human embryonic stem cells have enhanced of multiple forms of DNA damage. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2266–2274. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Felgentreff K, Du L, Weinacht KG, Dobbs K, Bartish M, Giliani S, Schlaeger T, DeVine A, Schambach A, Woodbine LJ, et al. Differential role of nonhomologous end joining factors in the generation, DNA damage response and myeloid differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323649111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]