Figure 5. The CPP potential shows a dependence on both time and size of change, while the central potential remains unaffected.

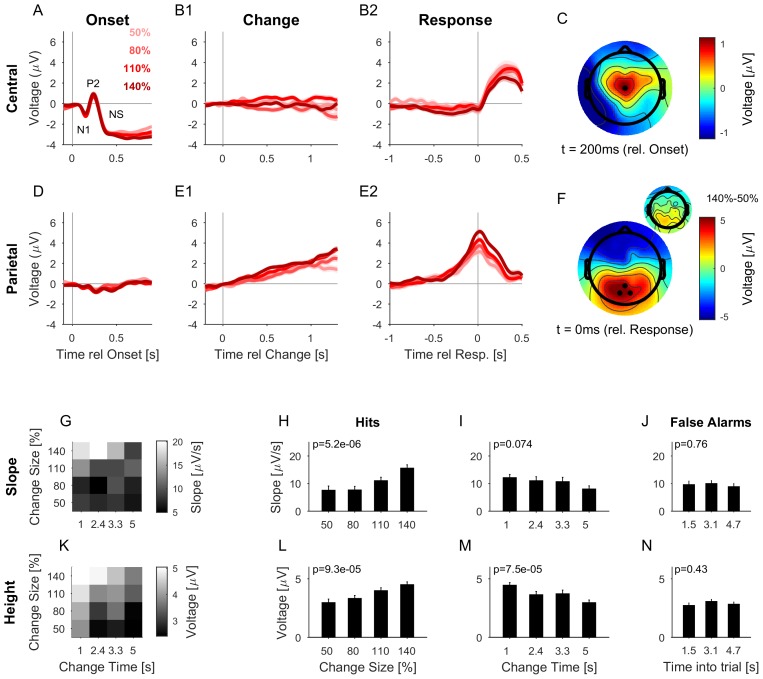

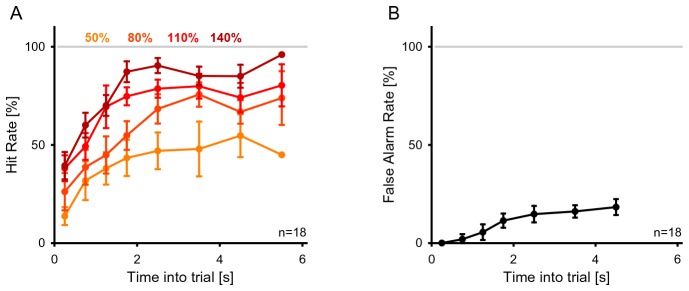

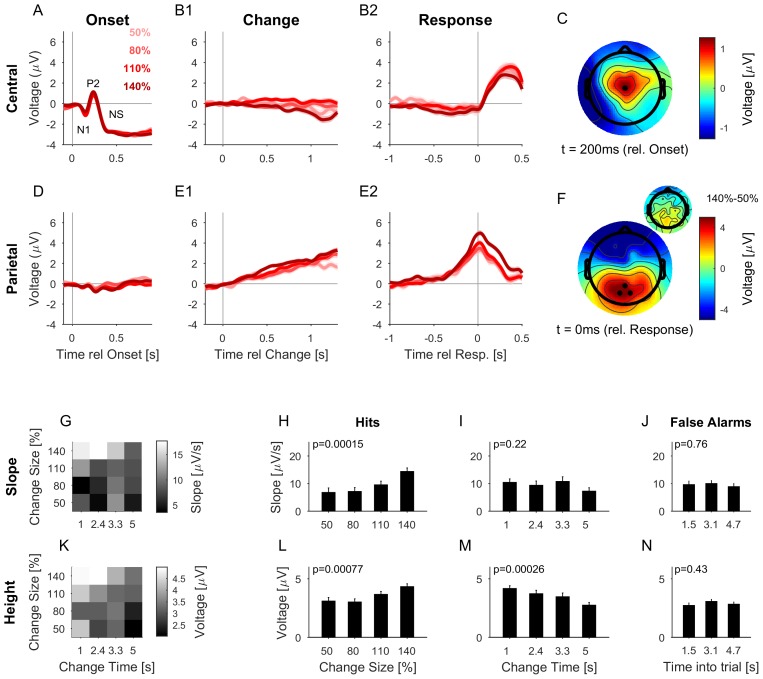

(A) After stimulus onset, the central potential (Ch. 1, black dot in C) shows a classical N1-P2 progression, followed by a sustained negative potential (labelled NS here). Different shades of red indicate different change sizes. Curves are average over all change times, to avoid crowding the plots. Note that the lowpass filtering at 20 Hz (common for all potentials) reduces the N1/P2 amplitudes below their typical size. (B1) Locked to the time of change, the central potential shows a slow negative trend, which, however, does not depend systematically on change size. (B2) Preceding the response, the central electrodes show no significant change in potential, which only starts to deviate from 0 after the button press. (C) At 200 ms after stimulus onset, the topography of the potential indicates a typical auditory onset response for bilateral stimulation, i.e. centered on Cz (El.1 in the equidistant layout, black dot). (D) The potential above the central parietal cortex (average over Ch. 14,27,28 in the equidistant cap, black dots in F) shows no substantial change at stimulus onset. (E1) Aligned to the time of change, the CPP electrodes show a progressive increase in potential, with some staggering according to change size. In comparison to the response-locked potentials, the present potential is wider and smaller since it is composed of responses at different times. (E2) In contrast to the central electrodes, the CPP electrodes show a clear increase before the response, peaking at or slightly after the response time. (F) The topography locked to the response is found to be centered over the parietal cortex, tending towards the occipital cortex (black dots mark Ch. 14,27,28). The inset shows the difference between the 140% and 50% condition, indicating that the difference in potential is also localized consistently with the average topography. Note, that there was no display change in the entire tone presentation, and a 0.5 s gap after the response, before the screen changed, hence, visual responses can be excluded. (G) CPP slope of the potential leading up to the response in relation to the different change time and size conditions was measured in a window of 300–50 ms before the response. (H) CPP slope depended significantly on change size (2-way ANOVA with change time and change size as factors, p<<0.001 for the change time as a factor). (I) CPP slope did not depend significantly on change time (ANOVA as above, p=0.07). (J) CPP slope for false alarms showed no significant dependence on the time into the trial (p=0.76, 1-way ANOVA). (K) Peak height of the CPP was measured in a symmetric window of 80 ms around the response time. (L) Peak height of the CPP showed a significant increase with change size (2-way ANOVA with change time and size as factors, p<<0.001 for change size). (M) Peak height depended significantly on change time, decreasing with longer change times (ANOVA as above, p<<0.001 for change time). (N) Peak heights for false alarms showed no dependence on time into the trial (p=0.43, 1-way ANOVA) but were significantly smaller than the hit trials (p<1e-9, 1-way ANOVA). Error bars indicate single SEMs for all plots.