Abstract

We describe a case of breakthrough Candida parapsilosis fungemia in an 80-year-old woman with pyoderma gangrenosum and rheumatoid arthritis. C. parapsilosis was detected in blood culture while the patient was treated with micafungin for a Candida glabrata bloodstream infection. The breakthrough infection was successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin B.

Keywords: Breakthrough infection, Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata, Pyoderma gangrenosum, Micafungin

1. Introduction

Candida spp. are the fourth leading cause of catheter-related bloodstream infections (BSIs) [1]. Among all Candida infections, >90% are caused by Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei [2], [3], [4]. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the echinocandins to C. parapsilosis are higher compared with those of most other Candida spp., raising the concern that echinocandins might not be the best treatment option for preventing C. parapsilosis infections [5], [6]. However, it has also been reported that echinocandins and other antifungals are equally effective in the treatment of C. parapsilosis BSIs [7]. We herein report an 80-year-old woman with pyoderma gangrenosum and rheumatoid arthritis in whom a breakthrough infection of C. parapsilosis was detected in blood culture during micafungin therapy for a C. glabrata bloodstream infection. The breakthrough infection was successfully treated with liposomal amphotericin B.

2. Case

An 80-year-old Japanese woman presented to the Dermatology Department of the Showa General Hospital on day 0 with a 1-month history of spreading ulcers due to pyoderma gangrenosum. Her past medical history included pyoderma gangrenosum, diabetes mellitus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Her daily medications included alfacalcidol, salazosulfapyridine, polaprezinc, methotrexate, lansoprazole, folic acid, diclofenac, and felbinac.

On initial physical examination, she had a temperature of 37.0 °C (98.6 °F) and a blood pressure of 111/45 mmHg, with a heart rate of 51 beats per minute. Her height was 145.5 cm, and her body weight was 45.5 kg. The patient presented with several ulcers on all her extremities but had otherwise unremarkable findings. The initial laboratory workup (day 0) showed hyperglycemia of 237 mg/dL, leukocytosis (white blood cell count [WBC], 16,040/µL), and abnormal renal function (blood urea nitrogen [BUN], 39.6 mg/dL; creatinine 1.64 mg/dL). An echocardiogram showed a heart rate of 38 beats per minute and a complete atrioventricular block.

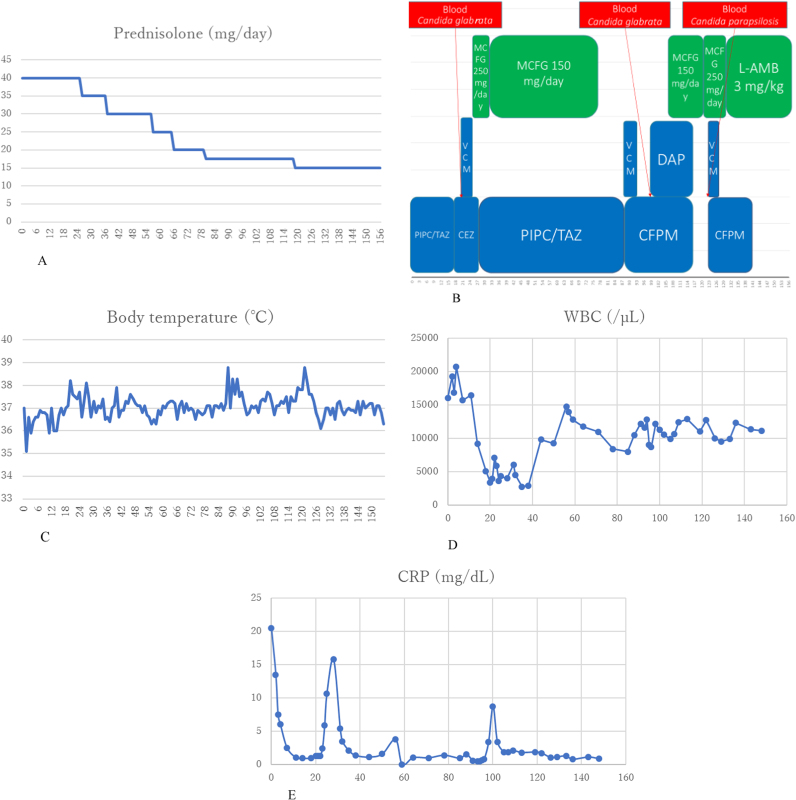

The clinical course is shown in Fig. 1. The patient was treated with prednisolone 40 mg/day for pyoderma gangrenosum; moreover, tazobactam/piperacillin was administered since an infection of the ulcers was suspected. On day +19, a pacemaker was implanted to treat the complete atrioventricular block. On day +23, Gram staining of the blood culture showed numerous yeast cells that were identified as C. glabrata (Table 1A), on API® ID32C (API-bioMérieux France). Micafungin 250 mg/day was administered (starting on day +23) followed by 150 mg/day (starting on day +29) after exclusion of fungal endophthalmitis. The pacemaker was removed to remove a possible source of infection on day +23. On day +30, a central venous (CV) catheter was inserted; it was subsequently removed and reinserted on day +38. On days +40 and +54, skin grafting was performed for the ulcers. As guidelines state that antifungal treatment should be completed >2 weeks after a negative blood culture (on day +31), micafungin therapy was discontinued on day +77 after a total of 54 days of treatment. On day +88, the CV catheter was removed and then reinserted. On day +105, Gram staining of the blood culture showed the recurrence of numerous yeast cells that were again identified as C. glabrata (Table 1B). As this was a recurrence of the C. glabrata BSI, we re-administered micafungin 150 mg/day and removed and reinserted the CV catheter. On day+109, another skin grafting procedure was performed. On day +120, Gram staining of the blood culture showed numerous yeast cells yet again; consequently, the micafungin dose was increased to 250 mg/day and the CV catheter was removed and then reinserted. On day +127, the blood culture and the CV catheter culture tested positive for C. parapsilosis (Table 1C), identified by API® ID32C (API-bioMérieux France).

Fig. 1.

Clinical course, A) Prednisolone dosages, B) Medications and dosages, C) Body temperature across time, D) White blood cell counts, E) C-reactive protein levels. CEZ, cefazolin; CFPM, cefepime; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAP, daptomycin; L-AMB, liposomal amphotericin B; MCFG, micafungin; PIPC, piperacillin; TAZ, tazobactam; VCM, vancomycin; WBC, white blood cell count.

Table 1A.

The MIC of Candida glabrata.

| Medicine | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| AMPH-B | 0.25 |

| 5-FC | <=0.12 |

| MCZ | 0.06 |

| FLCZ | 8 |

| ITCZ | 0.12 |

| MCFG | <=0.015 |

| VRCZ | 0.25 |

Table 1B.

The MIC of Candida glabrata.

| Medicine | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| AMPH-B | 0.5 |

| 5-FC | <=0.12 |

| MCZ | 0.06 |

| FLCZ | 8 |

| ITCZ | 0.25 |

| MCFG | 0.03 |

| VRCZ | 0.25 |

Table 1C.

The MIC of Candida parapsilosis.

| Medicine | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| AMPH-B | 0.5 |

| 5-FC | <=0.12 |

| MCZ | 0.12 |

| FLCZ | 0.25 |

| ITCZ | 0.06 |

| MCFG | 0.12 |

| VRCZ | <=0.015 |

Micafungin was switched to liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg/day), as this medication is effective for both C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis. On day+155, liposomal amphotericin B therapy was discontinued after a total treatment duration of 28 days, as the treatment had been provided >2 weeks after the negative blood culture result (day+134). On day+156, the CV catheter was removed and the patient was discharged from the hospital after successful treatment.

3. Discussion

We encountered a case of breakthrough C. parapsilosis fungemia in a patient who was treated with micafungin for a C. glabrata BSI.

Pfeiffer et al. showed that 50% of breakthrough invasive candidiasis cases among patients treated with micafungin were associated with C. parapsilosis [8]. However, no other Candida spp. had been identified in the patients in their study. To the best of our knowledge, the case presented herein is unique because C. parapsilosis was identified in the patient while she was treated for C. glabrata fungemia.

The MICs of the echinocandins to C. parapsilosis are higher compared with those of most other Candida spp. [9]. However, Ruiz et al. reported that echinocandins did not impair the treatment success in patients with C. parapsilosis BSIs [7].

Generally, echinocandins can be used to treat C. parapsilosis BSIs if the MICs of the echinocandins are below the reference values of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) methods [5]. In this case, the MIC of micafungin was low for C. parapsilosis (0.12 mg/L). According to CLSI® M27 S3 [10] and CLSI® M27 S4 [11], a MIC of 0.12 mg/L means that C. parapsilosis is susceptible to micafungin. Our case suggests that micafungin should not be the first-line treatment for C. parapsilosis BSIs even if the MIC is low enough to be classified as “susceptible”.

C. parapsilosis forms biofilms and is often associated with catheter-related BSIs [9], [12], [13], [14]. In our case, C. parapsilosis might have been introduced into the patient's body by the CV catheters. Removal of CV catheters is one of the most important therapies to treat candidiasis [11]. We removed the CV catheters every time when Gram staining of the patient's blood culture showed numerous yeast cells. The patient also had pyoderma gangrenosum; thus, ulcers might have also been primary entry sites for C. parapsilosis. Thaler et al. reported that wounds can be sources of candidiasis in patients with cancers [15]. Our patient was undergoing prednisolone therapy, and her past medical history included diabetes mellitus. Thus, the patient was considered an immunocompromised host.

In conclusion, we report a case of breakthrough candidemia of C. parapsilosis. This suggests that when C. parapsilosis is detected in a blood culture, echinocandins might not be the first-line treatment even if the MIC of the echinocandin is below the reference value.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical form

This study received no funding, and there are no potential conflicts of interest to declare. We obtained written and signed consent to publish the case report from the patient.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Kei Ogino and Yurie Ogura for critical reading of the manuscript. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Wisplinghoff H., Bischoff T., Tallent S.M., Seifert H., Wenzel R.P., Edmond M.B. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfaller M.A., Moet G.J., Messer S.A., Jones R.N., Castanheira M. Candida bloodstream infections: comparison of species distributions and antifungal resistance patterns in community-onset and nosocomial isolates in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2008–2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:561–566. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01079-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfaller M.A., Moet G.J., Messer S.A., Jones R.N., Castanheira M. Geographic variations in species distribution and echinocandin and azole antifungal resistance rates among Candida bloodstream infection isolates: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008–2009) J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:396–399. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01398-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orasch C., Marchetti O., Garbino J., Schrenzel J., Zimmerli S., Mühlethaler K. Candida species distribution and antifungal susceptibility testing according to European Committee on Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and new vs. old Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Clinical breakpoints: a 6-year prospective candidaemia survey from the fungal infection network of Switzerland. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:698–705. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaller M.A., Castanheira M., Diekema D.J., Messer S.A., Moet G.J., Jones R.N. Comparison of European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and Etest methods with the CLSI broth microdilution method for echinocandin susceptibility testing of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:1592–1599. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02445-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reboli Annette C., Rotstein Coleman, Pappas Peter G., Chapman Stanley W., Kett Daniel H., Kumar Deepali. Anidulafungin versus Fluconazole for Invasive Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:2472–2482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Ruiz M., Aguado J.M., Almirante B., Lora-Pablos D., Padilla B., Puig-Asensio M. Initial use of echinocandins does not negatively influence outcome in Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infection: a propensity score analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:1413–1421. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeiffer C.D., Garcia-Effron G., Zaas A.K., Perfect J.R., Perlin D.S., Alexander B.D. Breakthrough invasive candidiasis in patients on micafungin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2373–2380. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02390-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz L.S., Khouri S., Hahn R.C., da Silva E.G., de Oliveira V.K., Gandra R.F. Candidemia by species of the Candida parapsilosis complex in children's hospital: prevalence, biofilm production and antifungal susceptibility. Mycopathologia. 2013;175:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts: Third Informational Supplement M27-S3. Wayne, PA, USA, CLSI, 2008.

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts: Fourth Informational Supplement M27-S4. Wayne, PA, USA, CLSI, 2012.

- 12.Tumbarello M., Fiori B., Trecarichi E.M., Posteraro P., Losito A.R., De Luca A. Risk factors and outcomes of candidemia caused by biofilm-forming isolates in a tertiary care hospital. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anaissie E.J., Rex J.H., Uzun O., Vartivarian S. Predictors of adverse outcome in cancer patients with candidemia. Am. J. Med. 1998;104:238–245. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tumbarello M., Posteraro B., Trecarichi E.M., Fiori B., Rossi M., Porta R. Biofilm production by Candida species and inadequate antifungal therapy as predictors of mortality for patients with candidemia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:1843–1850. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00131-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thaler M., Pastakia B., Shawker T.H., O’Leary T., Pizzo P.A. Hepatic candidiasis in cancer patients: the evolving picture of the syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988;108:88–100. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]