Abstract

Introduction

The promotion of a healthy diet, physical activity and measurement of blood glucose levels are essential components in the care for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Smartphones offer a new way to promote health behaviour. The main aim is to investigate if the use of the Pregnant+ app, in addition to standard care, results in better blood glucose levels compared with current standard care only, for women with GDM.

Methods and analysis

This randomised controlled trial will include 230 pregnant women with GDM followed up at 5 outpatient departments (OPD) in the greater Oslo Region. Women with a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥9 mmol/L, who own a smartphone, understand Norwegian, Urdu or Somali and are <33 weeks pregnant, are invited. The intervention group receives the Pregnant+ app and standard care. The control group receives standard care only. Block randomisation is performed electronically. Data are collected using self-reported questionnaires and hospital records. Data will be analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Groups will be compared using linear regression for the main outcome and χ2 test for categorical data and Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for skewed distribution. The main outcome is the glucose level measured at the 2-hour OGTT 3 months postpartum. Secondary outcomes are a change in health behaviour and knowledge about GDM, quality of life, birth weight, mode of delivery and complications for mother and child.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is exempt from regional ethics review due to its nature of quality improvement in patient care. Our study has been approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services and the patient privacy protections boards governing over the recruitment sites. Findings will be presented in peer-reviewed journals and at conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT02588729, Post-results.

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, smartphone application, diet, physical activity, randomized controlled trial, pregnancy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Tailored health information through the Pregnant+ app in Norwegian, Urdu or Somali for women with gestational diabetes mellitus.

Automatic transfer of blood glucose levels from the glucometer to the app via Bluetooth Low Energy.

Privacy protection of participants' information through local storage instead of cloud service.

No blinding of participants, staff and researchers but blinding of those analysing samples and the statistician.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as glucose intolerance first identified in pregnancy, is an increasing problem among pregnant women worldwide.1 The prevalence is ranging from 1.7% to 20% depending on diagnosis criteria and population characteristics.1 On the basis of cases reported to the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry (NMBR), the prevalence of GDM in Norway is ∼2%.2 However, in a cohort study where all pregnant women were screened for GDM, the prevalence was 13% overall, with 11% in ethnic Norwegians and 14.6% in groups of non-European origin.3 It is therefore likely that GDM is underdiagnosed in the general population.

The majority of pregnant women with GDM recover from their glucose intolerance once the pregnancy is over.4 However, research suggests that a history of GDM increases the risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) later in life.5 6 Well-known risk factors for GDM include maternal obesity, advanced maternal age, ethnicity, family history of diabetes and a previous history of GDM.5 7 8 Women with GDM have an increased risk for pre-eclampsia, induction of labour, birth injuries, postpartum haemorrhage and caesarean section.9 GDM increases the infant's risk of macrosomia, birth injuries, neonatal hypoglycaemia and stillbirth.8 9

In addition, the Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study (HAPO) suggests an increased risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes with increasing levels of hyperglycaemia.10

In Norway, pregnant women with a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥9 mmol/L receive additional healthcare at a specialised Outpatient Department (OPD).11 New national Norwegian diabetic guidelines are being developed and expected to be implemented by 2017. Current care in Norway includes giving information about a healthy diet, physical activity and monitoring of blood glucose levels and observing the fetus through cardiotocography (CTG) and ultrasound.12 Health information is commonly given verbally, often accompanied by leaflets. Anecdotal evidence indicates that information on non-western food items in different languages is limited.

During the restricted time of clinic visits, information about healthy eating and physical activity competes with other components of care and other information. Health information via an app is easily and constantly available. Automatic transfer of blood glucose measurements to the app provides a novel way to monitor blood glucose levels. Nearly 80% of the adult population in Norway has a smartphone.13 Pregnant women are mostly young adults who are familiar with the use of electronic devices such as smartphones.

In a previous review of health behaviour interventions and use of apps, the authors found that apps are highly accepted by mobile phone users and may be a suitable way of providing health interventions. Even though previous smartphone-based randomised controlled trials (RCTs) show promising results for the self-management of diabetes and lifestyle factors,14 15 more research is needed to define the exact efficacy of apps on health outcomes.16

Since the prevalence of GDM is higher among certain groups of women from Asia and Africa compared with Norwegians, health information needs to be culture-sensitive, easy understandable and meet the individual's needs.3 17–19 A systematic review indicated better blood sugar control with culturally tailored counselling to ethnic minority patients with diabetes compared with standard care.20

We have developed an app for women with GDM, the Pregnancy+ app.21 This app is available in Norwegian, Urdu and Somali and consist of linguistically and culturally adapted information. These two groups of non-Western immigrants in Norway, Pakistani and Somali were selected due to their high number of annual births and high risk for GDM.3 17 The Pregnant+ app automatically transfers blood glucose measurements to the smartphone and provides a graphic overview indicating if the levels are satisfactory. Additionally, the app provides information about a healthy diet and physical activity. Our Pregnant+ app is meant for daily use by women, and not solely during consultation with health professionals.

The main aim of the study is to assess whether the use of the Pregnancy+ app in addition to standard care results in better glucose levels at routine OGTT, 3 months postpartum, compared with standard care only. Secondary outcomes are birth weight, mode of delivery and complications for mother and child.

Methods

Study design

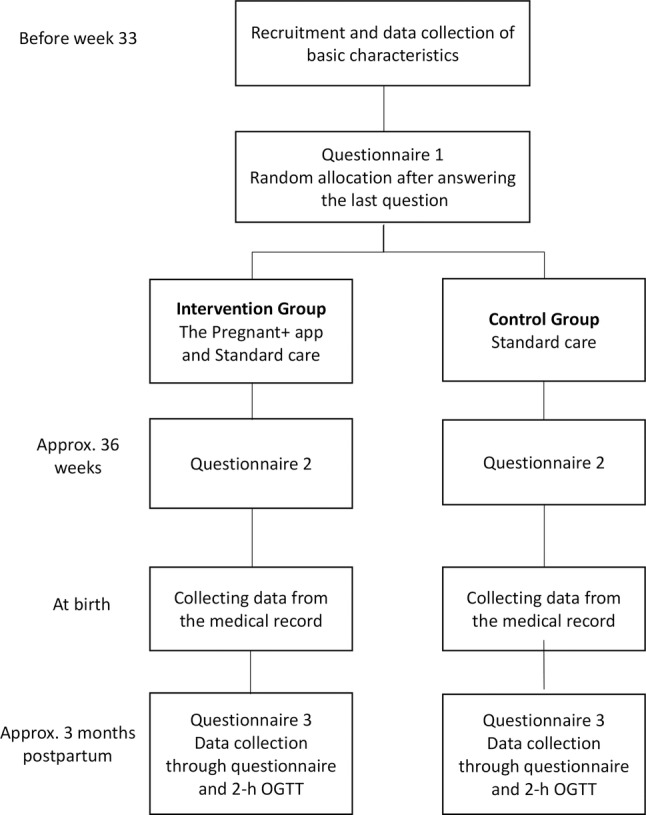

We will perform a multicentre RCT. This protocol includes the elements elaborated in the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) checklist.22 We recruit women attending the diabetic OPD at the Oslo University Hospital, Vestre Viken Hospital Trust and Akershus University Hospital. Study design and data collection are shown in the flow chart (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Design of the randomised controlled trial.

Participants, recruitment and blinding

Midwives and general practitioners refer pregnant women with recognised risk factors for GDM to a 2-hour OGTT at weeks 24–28 of gestation. On the basis of results of the OGTT, women are referred to the specialist diabetic OPD at the hospital. Participants in this study are selected among these referred women. The inclusion and the exclusion criteria for the participants are provided in table 1.

Table 1.

The inclusion and the exclusion criteria for the study population

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| <33 weeks pregnant | Diabetes Type 1 or 2 |

| A 2-hour OGTT ≥9 mmol/L | Twin pregnancy |

| Above 18 years old | Lactose and gluten intolerance |

| Owns a smartphone (iPhone or Android) |

|

| Understands Norwegian, Urdu or Somali |

We aim to recruit in total 230 women with GDM in the study. Women who decline to participate in this study are asked about their reason for declining. Answering options are: moving during pregnancy, no interest in the study, too time-consuming or other reasons.

The hospital staff at the OPD hand out the information brochure about the study and subsequently invite women to participate. This information brochure is included in the online supplementary material. Women who agree to participate sign two consent forms, one copy for themselves and one for the study administration. The consent form is included in the online supplementary material. Once written consent is obtained, questionnaire 1 (Q1) is filled out on an electronic tablet at the hospital. After completion of Q1, a computer-based program randomly allocates women to either receive access to the app and standard care or the group with standard care only. Randomisation is on a 1:1 basis with balanced variable blocks of 4. Women and the staff at the OPD were not blinded to the allocation. However, the staff analysing the blood samples will not be aware of which group the women belong to and neither will the staff providing care during labour. The statistician performing the analysis for the main outcome will be blinded to the allocation of the women until the data are analysed and primary results for the intervention group and control group are available.

bmjopen-2016-013117supp1.pdf (801.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013117supp2.pdf (151KB, pdf)

Standard care consists of information about a healthy diet, including limitation of sugar-rich products, increase in the amount of whole grain and vegetables and frequent small meals. The midwives and the diabetic nurse give standard care during the consultations. Pregnant women with GDM are advised to be regularly physically active during pregnancy. They are taught how to perform measures with the glucometer. Regular ultrasound and CTG are part of standard care for women with GDM.

The intervention with the Pregnant+ app

Our intervention consists of an app for pregnant women, the Pregnant+ app. The detailed development of the app is described in a previous publication.21 The Pregnant+ app aims to give women tailored information to support their management of GDM by adapted dietary intake and physical activity and feedback on blood glucose levels. The development of the Pregnant+ app was guided by the theory of the Health Belief Model (HBM). The HBM emphasises that the awareness of risk factors and perceived health benefits are essential components in behaviour change.23 The HBM has previously been used in a pregnant population to promote health benefits during pregnancy.24

The app contains four main icons: Blood glucose, Food and beverages, Physical activity and Diabetes information.21 Women can automatically (via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE)) or manually transfer the blood glucose values from the glucometer to the smartphone. When choosing the icon Blood glucose, the real-time blood glucose values appear in a graph and a green or red smiley indicates a good or too high blood glucose level, respectively. Pregnant women have the opportunity to print the blood glucose values at the hospital and to discuss them with the healthcare providers. The icon Food and beverages gives women general and culturally tailored information about healthy food choices. In our app, women can select a Norwegian, Somali or Pakistani food culture, also demonstrated by pictures. The Pregnant+ app has an approved link to food recipes from The Norwegian Diabetes Foundation. The icon Physical activity gives women suggestions for physical activity, the opportunity to register them and write down personal goals.

Diabetes information consists of a diabetic lexicon, a frequently asked questions section (FAQ) and general information on GDM and its treatment. The participants in the intervention group can download the Pregnant+ app at the hospital or at home. Women in the standard group may also download the Pregnant+ app but will only get access to a very limited version, with a link to the official websites of The Norwegian Directorate of Health and Norwegian Diabetes Foundation.

The Wireless Network and Information Security Group in Norway has contributed to the development of the Pregnant+ app ensuring users’ privacy. All the information on the smartphone is stored on the pregnant women's smartphone and not in a cloud.

The feasibility study

From April 2015 to July 2015, we performed a feasibility study at all five recruitment sites. The main aim of the feasibility study was to experience the speed of the recruitment, test of technical equipment like the blood sugar glucometer, the ability to answer the questionnaires on an iPad and the time used for including the women at the OPD. The feasibility study allowed us to improve some of the technical support needed for the study and implement recruitment routines at the hospitals. To increase the recruitment rate, we changed the inclusion criteria for participation from <32 to 33 weeks and decided to also include women with previous GDM. The experiences from the feasibility study allow us to inform women more correctly about the average time required to fill out the questionnaires.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of this study is the 2-hour blood glucose level measured at the routine OGTT (75 g) performed approx. 3 months postpartum.

Secondary outcomes and data collection

The secondary outcomes include a change in diet and physical activity from baseline to 36 weeks of gestation as measured by a modification of the Fit for Delivery questionnaire and the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ).25 26 Quality of life will be measured by a short version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EDS-5) and health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-SL) during pregnancy and postpartum.27 In addition, we will measure women’s knowledge of diabetes and one of the secondary outcomes is the blood glucose levels during pregnancy. We collect the blood glucose levels during pregnancy, not via the app but through questionnaire 2 and from the medical records registered at OPD visits. The main reason for not collecting these values via the app is due to the privacy concern and that the data from the control group are not available via the app. Other secondary outcomes are maternal complications during pregnancy and at birth such as: pre-eclampsia defined as raised blood pressure of ≥140/90 and significant proteinuria, induction of labour including prostaglandin, artificial rupture of membranes and oxytocin, operative instrumental birth defined as forceps, vacuum extraction, elective and emergency caesarean section, third and/or fourth degree sphincter rupture according to the national delivery ICD-10 code and postpartum haemorrhage defined as vaginal bleeding ≥500 and ≥1000 mL.28 Newborn health is measured by Apgar score <7 at 5 min, birth weight measured in grams, transfer to intensive care within 3 hours of birth and exclusive breast feeding at discharge.

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention, we will do a patient-level cost-utility analysis.29 30 Health benefit will be measured by using health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-SL) during pregnancy and postpartum.

To estimate costs, we collect data regarding changes in resources used in the health sector, time used for the intervention among women, expenses for the women and sick leave. The resource use related to the health sector will be based on data from the questionnaire (number of visits to maternity ward, GP, health centre, hospitals for treatments, etc) and literature. Time used on the intervention will be calculated by estimating the time used by the pregnant women to learn how to use of the app and time spent by the health professionals to teach them. Out-of-pocket expenses for the women will mainly be estimated by the travel cost related to handing over the app and training in the use of this. To estimate sick leave, we use the data from the questionnaire. The unit costs will mainly be based on marked prices, the reimbursement systems in Norway and the literature.

The results will be reported as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios and its CI, scatter plot in the cost-effectiveness plane and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.31 32 Additionally, we will perform sensitivity analysis for changes in unit cost.

Background variables such as civil status, age, income, weight prior to pregnancy (also collected through three questionnaires), education and mother tongue will be collected at baseline. The first and the second questionnaires, before 33 weeks and at 36 weeks, respectively, are filled out using an electronic tablet at the OPD. The third questionnaire is filled out at ∼3 months postpartum, via a link to a web page.

From the medical records, we collect the following data: blood glucose levels, complication during pregnancy and mode of delivery.

Participants' and health professionals' experiences with study participation will be evaluated in qualitative studies.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation is based on the following assumptions: power of 80%, a significance level of 5% and allowing for an attrition rate of 25%. A total of 230 participants, 115 participants per group, are required to detect a 10% difference between the intervention and control group, based on the assumption that the intervention group has a 2-hour glucose level at 3 months postpartum of 7.5 mmol/L (SD of 1.8 mmol/L). This power calculation was based on the results from several other RCT studies, investigating the effect of lifestyle changes to prevent T2DM.33–35 With a participation rate of 75%, it will take ∼20 months to recruit 230 women.

Data analysis

Data will be analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Primary outcome: glucose level as a continuous variable. This outcome will be analysed using linear regression with glucose as the dependent variable and type of intervention (intervention vs controls) as the independent variable. Further, the model will be adjusted for possible confounders as age and ethnicity.

In addition, glucose levels will be dichotomised as normal versus high and this outcome will be modelled using logistic regression.

Secondary outcomes included blood glucose levels during pregnancy taken from the medical records. These will be examined in the same way as the primary outcome.

Other secondary outcomes are women's knowledge of diabetes. For each correct answer, the responder will be given a score. The total sum will be computed and recorded at two time points, one before and the other after the delivery. Changes over time and between groups (intervention vs controls) will be modelled using mixed models for repeated measurements. Age and ethnicity will be included as fixed factors and thus controlled for as possible confounders.

Finally, the number of women with complications in both groups will be computed and the proportion will be compared using χ2 test. The scales for dietary habits and physical activity will be analysed as indicated by the authors.25 26

The main outcome is 2-hour blood glucose level measured as a continuous variable ∼3 months postpartum, using linear regression.

Crude differences between groups (intervention vs control) will be assessed using χ2 test for categorical data. Continuous data will be analysed using the t-test (when normally distributed) or Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test (when the distribution is skewed). Additionally, glucose levels will be dichotomised and logistic regression models used. The results will be expressed as ORs. All statistical models will be adjusted for ethnicity (Norwegian, Pakistani and Somali) as a possible confounder.

Descriptive statistics will be used to present the characteristics of the intervention and control group, providing frequencies (numbers) and proportion (percentages) for categorical variables. Continuous variables will be described with mean and SD. Missing data in this study will not be replaced.

Analyses will be performed using SPSS statistics V.22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) and Stata V.9.

Adverse events

The Pregnant+ app is additional to standard care. The app was developed together with healthcare providers from each of the recruitment sites and with user involvement.21 The healthcare providers approved the content which is largely in agreement with their local recommendations as national guidelines are under development. We therefore consider the risk of potential adverse events as minimal. If a woman loses her smartphone, the blood glucose values are still stored in the glucometer. The software of the app was regularly updated to be in line with new versions of mobile operating systems. However, we assume that these software updates will not affect the usage of the app.

All participants will be under close medical observation at their hospital. Events of harms can therefore be detected at an early stage and relevant care will be given.

In the feasibility study, we tested the glucometer, Diamond Mini, model DM30b from FORA and compared it with hospital measurements and found a good agreement between the measured levels. Any harmful events occurring will be reported by the project leader to the leader of the Department of Nursing and Health Promotion at Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, who is responsible for the study. Harmful events and the appropriate response to these will in addition be discussed within the research group.

Data management

Data from this study will be stored encrypted on an electronic server at the University Graduate Centre at Kjeller, Norway. The data from the glucometer, personal goals and notes registered in the Pregnant+ app will be on women's smartphones only. These data are not collected for the study. All the data will be treated anonymously. App usage data are collected, with specific information about the clicks per page and the duration of the visit of each page. Data from the medical records will be collected by the hospital staff and noted down on an outcome form. The written consent forms, together with the outcome forms, will initially be stored in a locked cupboard at the hospital and then be transferred by a PhD student to the Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences where they will again be stored in a locked cupboard. The personal data which identify the women will be deleted in the beginning of 2018, but anonymised information will be used for follow-up studies, depending on future funding.

Dissemination

In our study, we will follow the Word Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net).36 Women meeting the inclusion criteria will be informed that neither the decision to participate nor declining to participate will influence their care. Participation is voluntary and women can withdraw whenever they like. Hospital staff have been made aware of this. The intervention, the Pregnant+ app, is a non-invasive method. The FORA Diamond Mini glucometer is used in this study and has ISO certificate approval. The glucometer has a BLE function allowing automatic transfer of blood glucose levels from the device to the smartphone.

This study has been considered by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Medical Health Research Ethics, REK and by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services and the patient privacy protections boards governing over the recruitment sites.

Important modifications to the protocol are updated on the ClinicalTrials.gov website and disseminated to all relevant parties. We have a contractual agreement with key collaborators determining access to trial data and authorship.

Data services

Sensitive information such as: participant’s name, project ID-number, phone number, country of birth from The Recruitment form and information from the medical records are stored in a locked cupboard at the hospitals. Everybody involved in recruitment at each hospital has signed a confidentiality form.

Results from the study will be presented in scientific journals and at national and international congresses.

Discussion

There is vast evidence that GDM is associated with detrimental effects for the health of pregnant women and their offspring.8 9 In addition, the HAPO study showed an increased risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes with increasing levels of hyperglycaemia.10 Thus, all efforts preventing hyperglycaemia during pregnancy are important.

Essential elements of GDM treatment are improvement in diet and increased physical activity. Health professionals constantly search for better ways of encouraging healthy behaviour. Since verbal information may be easily forgotten and leaflets can be lost, the use of apps in health interventions appears appropriate.16 37

Compared with leaflets and verbal information, apps are more flexible and have more variable modes of communication (text, pictures, sound, interactivity) and functionality (response on blood sugar levels). The Pregnant+ app includes information about a healthy diet, physical activity and gestational diabetes, which is always near at hand on the woman's smartphone. One important component of the Pregnant+ app is the automatic transfer of the blood glucose values from the glucometer to the smartphone. The blood glucose values are visually presented in either a graph or a table. This overview and information if the blood glucose values are too high allows women to gain better control over their blood glucose levels.21 In addition, the availability of essential information on GDM, hospital routine and relevant phone numbers may decrease worries, distress and hospital visits.

We developed the Pregnant+ app in Norwegian and subsequently translated and customised it for women speaking Somali or Urdu, as they are among the identified risk groups.3 12 The Pregnant+ app was developed for everyday use and may be used during consultations, for example, to refer to blood glucose levels or advice given.21

Although most of the women with GDM recover from the condition after birth, several studies have shown an increased risk of developing type 2 later in life.38 Research suggests that pregnant women with the highest blood glucose levels during pregnancy have the highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future.38

Therefore, strategic interventions to reduce hyperglycaemia for women with GDM may prevent T2DM among women with GDM or recent GDM.5 A recently published article demonstrated that a smartphone with an interactive blood-glucose-management was convenient and acceptable for women with GDM.39 In another study with a smartphone application for GDM, the authors found the app to be useful in managing GDM.40 Women adopting a healthy lifestyle will positively influence their health during pregnancy and later in life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in the feasibility study and the ongoing RCT study. The authors thank the health professionals at the outpatient departments and bachelor's and master's students from the Faculty of Health Sciences for recruitment and data collection. The authors thank the Clinic of Innovation at Oslo University for supporting this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML, AM, IB, LMG-H, AML and LET planned the design of the study. ML, MCS and IB performed the power calculation and planned the analysis of the data. LMG-H, ML, JN, IKB and IB developed the Pregnant+ app intervention. ML, LMG-H, KB, LET, AM and IB developed and SF programmed the questionnaires. IB, JN, LMG-H and the hospital staff at the five OPDs conducted the feasibility study. JN and SF worked with technical support. IB, ML, LMG-H and AFJ wrote the draft and all authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by the Norwegian Research Council (http://www.forskningsradet.no; identifier: 228517).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study has been evaluated by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical Health Research Ethics South East (REK) but is exempt from regional ethics review due to its nature of quality improvement in patient care (id-number: 2014/5068). The study has been approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (id-number: 2014/38942) and the patient privacy protections boards governing over the recruiting sites.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This protocol is available for the public.

References

- 1.Galtier F. Definition, epidemiology, risk factors. Diabetes Metab 2010;36(Pt 2):628–51. 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwegian, Institute, of, Public, Health. Diabetes in Norway-Norwegian Institute of Public Health Rapport 2014. http://www.fhi.no/eway/default.aspx?pid=239&trg=Content_7242&Main_6157=7239:0:25,8904&MainContent_7239=7242:0:25,8906&Content_7242=7244:110410::0:7243:1:::0:0#eHandbook1104107 (accessed 22 Feb 2016).

- 3.Jenum KA, Richardsen KR, Berntsen S et al. . Gestational diabetes, insulin resistance and physical activity in pregnancy in a multi-ethnic population—a public health perspective. Norsk Epidemiologi 2013;23:45–54. 10.5324/nje.v23i1.1602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skupień J, Cyganek K, Małecki MT. Diabetic pregnancy: an overview of current guidelines and clinical practice. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014;26:431–7. 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD et al. . Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:1773–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauenborg J, Hansen T, Jensen DM et al. . Increasing incidence of diabetes after gestational diabetes: a long-term follow-up in a Danish population. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1194–9. 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim C. Gestational diabetes: risks, management, and treatment options. Int J Womens Health 2010;2:339–51. 10.2147/IJWH.S13333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider S, Hoeft B, Freerksen N et al. . Neonatal complications and risk factors among women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:231–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR et al. . Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1991–2002. 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe LP, Metzger BE, Dyer AR et al. , HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: associations of maternal A1C and glucose with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 2012;35: s574–80. 10.2337/dc11-1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksen T, Thordarson H. Svangerskapsdiabetes. Veileder i Fødselhjelp, 2014. http://legeforeningen.no/Fagmed/Norsk-gynekologisk-forening/Veiledere/Veileder-i-fodselshjelp-2014/Diabetes-i-svangerskapet/ (accessed 22 Feb 2016).

- 12.Helsedirektoratet. http://www.helsebiblioteket.no/retningslinjer/diabetes/12.diabetes-og-graviditet/12.3-svangerskapsdiabetes (accessed 12 Feb 2016).

- 13.Medie Norge. Andelen Som Har Smartphone. Oslo, Norway: Medienorge, 2014. (In Norwegian). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmen H, Torbjørnsen A, Wahl AK et al. . A mobile health intervention for self-management and lifestyle change for persons with type 2 diabetes, part 2: one-year results from the Norwegian randomized controlled trial RENEWING HEALTH. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;2:e57 10.2196/mhealth.3882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glynn LG, Hayes PS, Casey M et al. . Effectiveness of a smartphone application to promote physical activity in primary care: the SMART MOVE randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e384–91. 10.3399/bjgp14X680461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne HE, Lister C, West JH et al. . Behavioral functionality of mobile apps in health interventions: a systematic review of the literature. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e20 10.2196/mhealth.3335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macaulay S, Dunger DB, Norris SA. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e97871 10.1371/journal.pone.0097871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:439–55. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiavo R. Health communication: from theory to practice. 1st edn San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attridge M, Creamer J, Ramsden M et al. . Culturally appropriate health education for people in ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(9):CD006424 10.1002/14651858.CD006424.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garnweidner-Holme LM, Borgen I, Garitano I et al. . Designing and developing a mobile smartphone application for women with gestational diabetes mellitus followed-up at diabetes outpatient clinics in Norway. Healthcare (Basel) 2015;3:310–23. 10.3390/healthcare3020310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr 1974;2:354–86. 10.1177/109019817400200405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce EE, Evenson KR, Downs DS et al. . Strategies to promote physical activity during pregnancy: a systematic review of intervention evidence. Am J Lifestyle Med 2013;7:38–50 10.1177/1559827612446416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fit for fødsel questionnaire. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/132 (accessed 22 Feb 2016).

- 26.Çırak Y, Yılmaz GD, Demir YP et al. . Pregnancy physical activity questionnaire (PPAQ): reliability and validity of Turkish version. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:3703–9. 10.1589/jpts.27.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Samuelsen SO et al. . A short matrix version of the Edinburgh Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;116:195–200. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision, ICD-10 Version, 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en (accessed 25 Nov 2016).

- 29.Drummond M, Sculpher M, Claxton K et al. . Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th edn Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS et al. . Economic evaluation in clinical trials. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briggs A. Handling uncertainty in economic evaluation and presenting the results. In: Drummond M, McGuire A, eds. Economic evaluation in health care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001:172–214. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. Pulling cost-effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: a non-parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ 1997;6:327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telle-Hjellset V, Råberg Kjøllesdal MK, Bjørge B et al. . The InnvaDiab-DE-PLAN study: a randomised controlled trial with a culturally adapted education programme improved the risk profile for type 2 diabetes in Pakistani immigrant women. Br J Nutr 2013;109:529–38. 10.1017/S000711451200133X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh D, Miller YD, Marshall AL et al. . Health-enhancing physical activity behaviour and related factors in postpartum women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13:42–5. 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldroyd JC, Unwin NC, White M et al. . Randomised controlled trial evaluating lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2006;72:117–27. 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Word Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. http://www.wma.net (accessed 28 Apr 2016).

- 37.Årsand E, Frøisland DH, Skrøvseth SO et al. . Mobile health applications to assist patients with diabetes: lessons learned and design implications. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:1197–206. 10.1177/193229681200600525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1862–8. 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirst JE, Mackillop L, Loerup L et al. . Acceptability and user satisfaction of a smartphone-based, interactive blood glucose management system in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9:111–15. 10.1177/1932296814556506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jo S, Park HA. Development and evaluation of a smartphone application for managing gestational diabetes mellitus. Healthc Inform Res 2016;22:11–21. 10.4258/hir.2016.22.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013117supp1.pdf (801.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013117supp2.pdf (151KB, pdf)