Abstract

Objectives

An increased risk of tuberculosis (TB) has been reported in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists, an issue that has been highlighted in a WHO black box warning. This review aimed to assess the risk of TB in patients undergoing TNF-α antagonists treatment.

Methods

A systematic literature search for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was performed in MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane library and studies selected for inclusion according to predefined criteria. ORs with 95% CIs were calculated using the random-effect model. Subgroup analyses considered the effects of drug type, disease and TB endemicity. The quality of evidence was assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Results

29 RCTs involving 11 879 patients were included (14 for infliximab, 9 for adalimumab, 2 for golimumab, 1 for etanercept and 3 for certolizumab pegol). Of 7912 patients allocated to TNF-α antagonists, 45 (0.57%) developed TB, while only 3 cases occurred in 3967 patients allocated to control groups, resulting in an OR of 1.94 (95% CI 1.10 to 3.44, p=0.02). Subgroup analyses indicated that patients of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) had a higher increased risk of TB when treated with TNF-α antagonists (OR 2.29 (1.09 to 4.78), p=0.03). The level of the evidence was recommended as ‘low’ by the GRADE system.

Conclusions

Findings from our meta-analysis indicate that the risk of TB may be significantly increased in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists. However, further studies are needed to reveal the biological mechanism of the increased TB risk caused by TNF-α antagonists treatment.

Keywords: TNF-α antagonists, meta-analysis, RCTs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This meta-analysis evaluated the tuberculosis (TB) risk of all TNF-α antagonists across a variety of conditions in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with low heterogeneity.

In addition to the diseases most commonly treated by TNF-α antagonists (rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis), the review included studies that involved patients with asthma, sarcoidosis and graft-versus-host disease.

The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, which has been recommended for grading evidence by the British Medical Journal since 2006.

The relatively short follow-up period in the RCTs might have caused an underestimation of the TB rates.

Introduction

Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays a central role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and other immune-mediated or inflammation-related diseases.1 Therefore, it is a critical molecular member in targeted biological interventions,2 and the advent of TNF-α-directed targeted therapies represents a major advance in the treatment and management of conditions such as RA, psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and IBD,3–5 improving the quality of life for these patients.6 Increasingly, evidence indicate that TNF-α antagonists may possess promising therapeutic potential in many TNF-α-mediated diseases. Our previous study showed that TNF-α played a critical role in the occurrence and development of inflammation and tumour, and the TNF-α monoclonal antibody which we prepared as a TNF-α antagonist significantly suppressed the growth of breast cancer in an animal model.7

To date, five TNF-α antagonists have been used in clinical practice: etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab and certolizumab pegol. Although their therapeutic efficacy has been confirmed, the side effects of these TNF-α antagonists need to be considered carefully in clinical practice.8 An increased risk of tuberculosis (TB) among patients receiving TNF-α antagonists has been observed,9 and several meta-analyses have evaluated the risk of TB in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists or with specific conditions.10–13 Nevertheless, the association between TNF-α antagonists and an increased risk of TB remains uncertain.

With the aim of further clarifying the issue, this meta-analysis compared the risk of TB between TNF-α antagonists treatment and control groups in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) focusing on any disease condition. A secondary objective was to investigate the association of the rate of active TB with the type of medication, the disease condition and the location of study.

Materials and methods

The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.14

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We performed a search for all published RCTs that reported TB risk among patients treated with any of the existing five TNF-α antagonists: etanercept (ETN), adalimumab (ADA), infliximab (IFX), golimumab (GOL) and certolizumab pegol (CZP). Studies were selected for inclusion according to predefined inclusion criteria:

Participants: Adults (aged 16 years or older) with any disease included in studies of any of the five TNF-α antagonists.

Interventions: TNF-α antagonists ETN, ADA, IFX, GOL or CZP with or without standard-care treatment for any medical condition.

Comparators: Placebo with or without standard-care treatment or standard-care treatment alone.

Outcomes: Diagnosis of TB, TB reactivation, miliary or cavitary TB of the lung or any other body organ.

Study design: RCTs.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) duplicated studies or studies based on unoriginal data, (2) studies that did not report TB incidence, (3) studies that did not observe TB events and (4) articles not published in English.

Data sources and search strategies

We systematically searched for reports of trials and systematic reviews up to December 2015 from the following online databases: MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Library. No restrictions were imposed with regard to region and time. To identify all RCTs, a highly sensitive search strategy developed on the basis of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was applied, which combined with the following key terms: ‘etanercept’, ‘adalimumab’, ‘infliximab’, ‘golimumab’, ‘certolizumab’ and ‘TNF-α antagonist’ (The MEDLINE search strategy is provided in online supplementary appendix 1). In addition, the reference lists of all topic-related review articles, reports or meta-analyses were searched for potentially relevant studies.

bmjopen-2016-012567supp_appendices.pdf (966.7KB, pdf)

Selection of studies

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all records retrieved by the searches and identified studies that were potentially eligible for inclusion. Full-text versions were obtained, and these were independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between reviewers at both stages of screening were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Data extraction and methodological quality assessment

Data extraction was conducted independently by two investigators, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. For each included study, we extracted essential information, including publication details, sample size, characteristics of trial participants, timing of assessment, interventions/comparisons, incidence cases of TB, performance of TB screening prior to therapy and geographic location of the study classified according to the incidence rate (IR) of TB (WHO, incidence TB estimation, 2014). Countries with an IR ≥40/100 000 are considered as high-incidence TB areas. The methodological quality of all included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane collaboration's tool. The tool contains seven dimensions: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias. Studies were considered as low risk of bias when all these key aspects were assessed to be at low risk.

Statistical analysis

Principal statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.2 software according to the Cochrane handbook. On the basis of events reported by included studies, the number of patients developing TB was compared between the placebo-controlled or standard-care populations and patients receiving at least one dose of TNF-α antagonists. Statistical heterogeneity among results was evaluated by using the I² statistic with the significance level set at 0.1. Meta-analyses were performed using the random-effects model. Results were presented as OR and its 95% CI. An OR >1 suggests a higher risk of TB than the control. Publication bias was tested by funnel plots, Egger's regression method and Begg's rank correlation method, using Stata software (V.11.0, College Station, Texas, USA). To evaluate the influence of all single studies on the pooled outcome, we also performed sensitivity analysis through the leave-one-out approach. Stratified analyses were performed by type of medication, disease being treated and estimated TB rates of studies' geographic locations.

Quality of evidence

We assessed the quality of evidence using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methods.15 GRADEprofiler 3.6 software was applied to create the evidence profile. The GRADE approach categorises the quality of evidence as follows: (1) high quality (further research is extremely unlikely to change the credibility of the pooled results); (2) moderate quality (further research is likely to influence the credibility of pooled results and may change the estimate); (3) low quality (further research is extremely likely to influence the credibility of pooled results and is likely to change the estimate) and (4) very low quality (the pooled results have extreme uncertainty).

Results

Search results

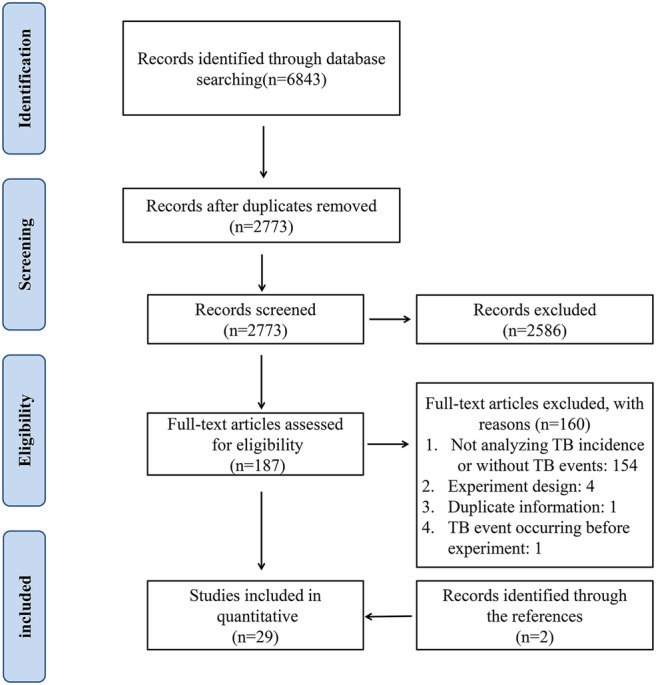

A total of 6843 study records were identified following the search strategy; 2773 references were left after removing duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 187 references progressed to the next stage, in which articles were re-evaluated based on full texts. Ultimately, 27 RCTs met the inclusion criteria and were included in our meta-analysis. In addition, two records were added after checking the references of previous systematic reviews.16 17 The PRISMA flow diagram of study selection is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics and methodological quality

The 29 included studies involved a total of 11 879 patients.16–44 The duration of outcome assessment in included studies ranged from 8 weeks to 3 years. Fourteen trials assessed infliximab, two trials assessed golimumab, nine trials assessed adalimumab, one trial assessed etanercept and three trials assessed certolizumab pegol. Thirteen RCTs were in areas with a low IR of TB and eleven in areas with a high incidence; this information was unavailable in the remaining five RCTs (table 1). TB screening was reported in 26 RCTs but was not carried out in 3 trials. A total of 45 TB cases occurred among 7912 patients treated with TNF-α antagonists and only 3 cases developed in 3967 patients in the control groups (see online supplementary appendix 2). The methodological quality assessments of included studies are summarised in online supplementary appendix 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials included

| First author | Year | Disease | Timing of assessment | Comparison | EA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim16 | 2007 | RA | Week 24 | PBO vs ADA | No |

| Rutgeerts17 | 2005 | UC | Week 54 | PBO vs IFX | Yes |

| Baranauskaite18 | 2012 | PsA | Week 16 | MTX vs IFX+MTX | Yes |

| Barker19 | 2011 | Ps | Week 24 | MTX vs IFX | – |

| Braun20 | 2002 | AS | Week 12 | PBO vs IFX | No |

| Breedveld21 | 2006 | RA | Year 2 | MTX vs ADA/ADA+MTX | – |

| Chen22 | 2009 | RA | Week 12 | MTX vs ADA+MTX | No |

| Colombel23 | 2010 | CD | Week 20 | AZA vs IFX/IFX+AZA | – |

| Couriel24 | 2009 | GvH | Month 6 | MP vs IFX+MP | No |

| Judson25 | 2014 | Sarcoidosis | Week 44 | PBO vs GOL | – |

| Kavanaugh26 | 2013 | RA | Week 26 | PBO+MTX vs ADA+MTX | Yes |

| Kennedy27 | 2014 | RA | Week 12 | PBO vs ADA | No |

| Keystone28 | 2004 | RA | Week 52 | PBO+MTX vs ADA+MTX | No |

| Keystone29 | 2008 | RA | Week 52 | PBO+MTX vs CZP+MTX | Yes |

| Maini30 | 1999 | RA | Week 102 | DMARDs vs IFX+DMARDs | No |

| Nam31 | 2014 | RA | Week 78 | PBO+MTX vs IFX+MTX | No |

| Reich32 | 2012 | Ps | Week 12 | PBO vs CZP | No |

| Schiff33 | 2014 | RA | Year 2 | ABA+MTX vs ADA+MTX | No |

| Schiff34 | 2008 | RA | Year 1 | PBO+MTX vs IFX+MTX | Yes |

| Sieper35 | 2014 | AS | Week 28 | PBO+NPX vs IFX+NPX | Yes |

| Smolen36 | 2009 | RA | Week 24 | PBO+MTX vs CZP+MTX | Yes |

| St Clair37 | 2004 | RA | Week 54 | PBO+MTX vs IFX+MTX | No |

| Suzuki38 | 2014 | UC | Week 8 | PBO vs ADA | No |

| Tam39 | 2012 | RA | Month 6 | MTX vs IFX+MTX | Yes |

| Van Den Bosch40 | 2002 | AS | Week 12 | PBO vs IFX | - |

| van der Heijde41 | 2007 | RA | Year 3 | MTX vs ETN/ETN+MTX | Yes |

| van Vollenhoven42 | 2011 | RA | Week 24 | PBO+MTX vs ADA+MTX | Yes |

| Wenzel43 | 2009 | Asthma | Week 76 | PBO vs GOL | No |

| Westhovens44 | 2006 | RA | Week 22 | PBO+MTX vs IFX+MTX | Yes |

ABA, abatacept; ADA, adalimumab; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; AZA, azathioprine; CD, Crohn's disease; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; EA, endemic area of TB; ETN, etanercept; GOL, golimumab; GvH, graft-versus-host disease; IFX, infliximab; MP, methylprednisolone; MTX, methotrexate; NPX, naproxen; PBO, placebo; Ps, plaque psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UC, ulcerative colitis.

TB risk and TNF-α antagonists

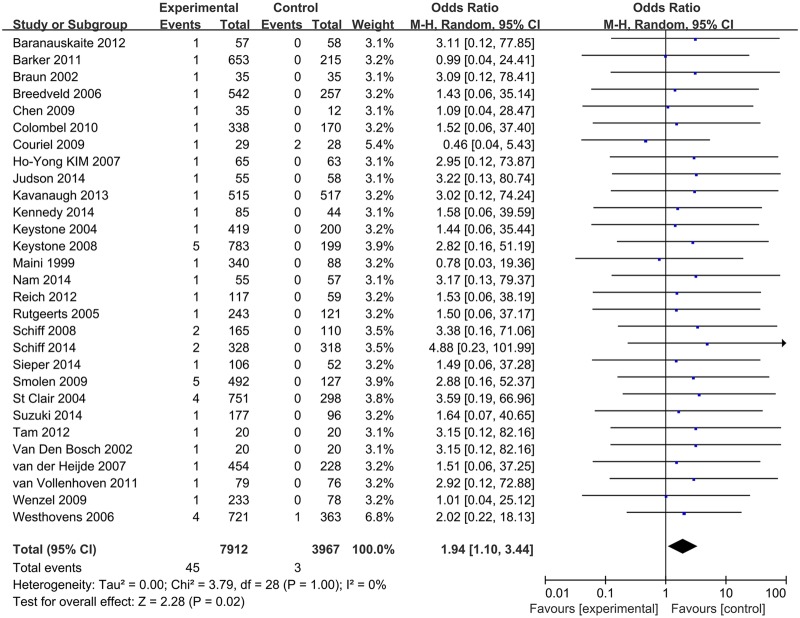

Pooled analysis determined that treatment with TNF-α antagonists was associated with an increased occurrence of TB compared with control groups (OR 1.94 (1.10, 3.44), p=0.02; figure 2). No significant heterogeneity was detected (I²=0%). The funnel plot revealed no obvious asymmetry in distribution, suggesting a low likelihood of publication bias (see online supplementary appendix 4), and this was statistically confirmed by Begg's test (p=0.348) and Egger's regression asymmetry test (p=0.321). Sensitivity analysis using random-effects model suggested that pooled result was not affected substantially by any of the included studies (see online supplementary appendix 5).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of TB risk associated with TNF-α antagonists. TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α; TB, tuberculosis.

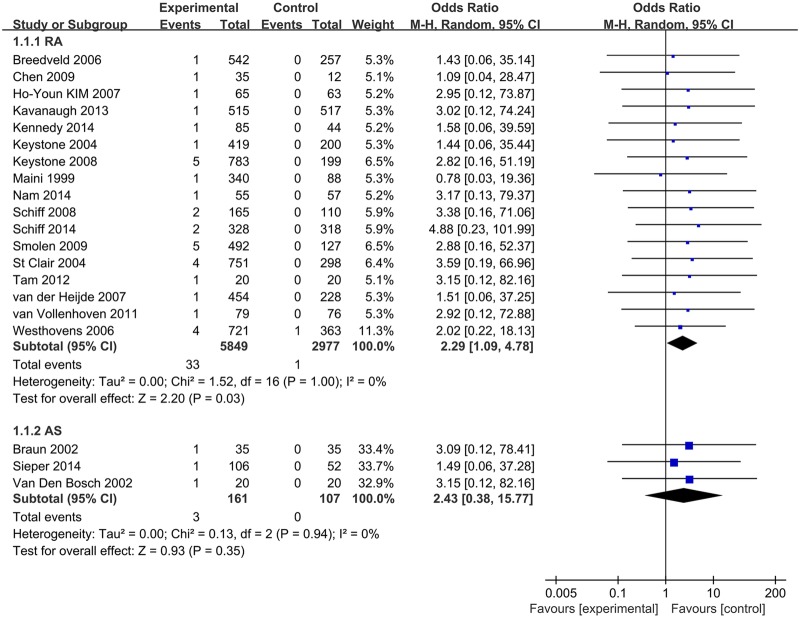

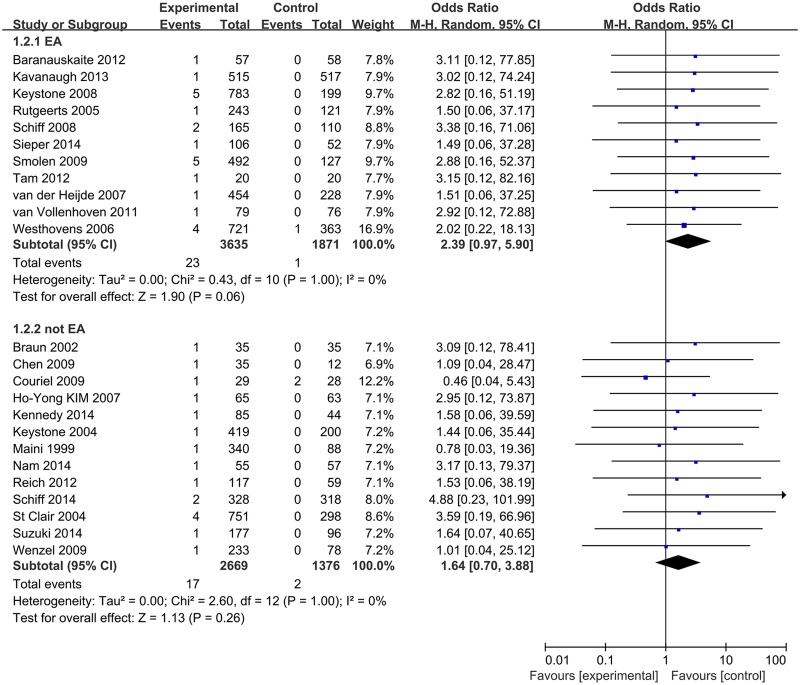

We performed subgroup analyses based on type of medication, disease under treatment and TB rate of the geographic location. In these analyses, the type of drugs was not associated with statistically significant differences in the risk of TB between patients treated with TNF-α antagonists and control groups (IFX: 1.82 (0.82–4.06), ADA: 2.11 (0.73–6.12), CZP: 2.38 (0.42–13.42)) (see online supplementary appendix 6). When grouped for disease, a significantly increased TB risk was associated with anti-TNF-α drugs in RA patients (OR 2.29 (1.09 to 4.78), p=0.03) (figure 3). When analysed according to estimated TB rates of studies' geographic locations, ORs for studies in high or low TB rate areas were 2.39 (95% CI 0.97 to 5.90, p=0.06) and 1.64 (95% CI 0.70 to 3.88, p=0.26), respectively (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of TB risk in RA and AS patients. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TB, tuberculosis.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of TB risk in high or low TB rate areas. TB, tuberculosis.

GRADE profile evidence

The results of assessing the quality of evidence are shown in online supplementary appendix 7. The quality for the main result was recommended as ‘low’ by the GRADE system.

Discussion

TNF-α antagonists have been widely used in many rheumatic diseases due to their considerable therapeutic effects and are promising candidates for future clinical applications in many other relevant diseases.7 24 However, an increased risk of TB has been observed among patients receiving anti-TNF treatments,9 an issue that has been highlighted by WHO in a black box warning for TB and other opportunistic infections.

This meta-analysis aimed to consider TB risk in any patient treated with TNF-α antagonists, with the premise that the adverse event profile of TNF-α antagonists would be similar irrespective of the condition being treated. Twenty-nine published RCTs involving 11 879 patients were eventually included. In addition to the diseases most commonly treated with TNF-α antagonists (RA, UC, AS and PsA), this review also included studies that involved patients with asthma, sarcoidosis and Graft-versus-Host disease (GvH). We found that the risk of TB was statistically significantly increased in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists. With patients being treated with any TNF-α antagonist for any disease included, the risk of TB was almost doubled compared with those in normal care or placebo comparator arms. This result is in accordance with previously reported suspicions that TNF-α antagonists could increase TB risk, but differs from the findings of two previous meta-analyses on this topic, which found no significantly increased TB risk among patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases or RA treated with different TNF-α antagonists.10 11 One possible reason for this discrepancy may be the relatively small number of patients included in those meta-analyses.

In order to take into account the effects of disease condition and the rate of TB in the background population on the pooled results, subgroup analyses were performed. When patients with RA were considered alone, the level of increased risk of TB in RA patients receiving TNF-α antagonists, compared with placebo or normal care groups, was higher than the increased risk among patients in any disease condition. Although it has been reported that RA patients showed an increased risk of TB when compared with the general population,45–47 the potential for anti-TNF drugs to increase this risk further should not be ignored. It was also expected that patients in endemic areas would have a higher risk of TB after treatment with anti-TNF agents. While the difference in TB incidence between anti-TNF treated patients and control groups was not statistically significant (p=0.06), the trend towards higher incidence was enough to suggest the likelihood of a repeatable difference, which indicates that safety studies should include patients from these areas to provide a true profile of the risk of infection. No differences in TB incidence were identified between anti-TNF-treated patients and controls when subgroup analyses were conducted by single drug types. However, it is likely that this is a result of the small number of included patients.

TNF-α is an immune mediator that plays a critical role in protective mechanism against infections, especially TB. TNF increases the phagocytic capacity of macrophages and enhances intracellular killing of mycobacterium via the generation of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates, effectively synergising with interferon (IFN)-γ.48 TNF-α is also involved in the pathological changes of latent tuberculous infection (LTBI), especially in maintaining the formation and function of granuloma which prevents mycobacterium from disseminating into the blood.49 These TNF-mediated immune mechanisms may explain the reason for the increased risk of TB in patients receiving anti-TNF agents’ treatment.

The results of this review may have direct implications in the management of a large number of patients treated currently with biologics. Therapeutic approaches that include intensive screening and surveillance seem to be advisable when TNF-α antagonists are used. One review of infection risk associated with anti-TNF-α agents suggested that a patient eligible for such treatment should undergo a careful medical history and tests such as the TB skin test (TST) or chest X-ray to assess the risk of TB re-activation.50 Interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) is also established as an alternative to the TST in TB infection diagnosis, especially in the diagnosis of LTBI due to the higher specificity.51

Previous studies have shown that prophylaxis in patients before or during anti-TNF-α therapy with standard anti-TB regimen prevented reactivation effectively.52 53 One study estimated that preventive treatment in patients with LTBI can reduce the risk of reactivation by 65%.10 Some countries have formulated national guidelines to deal with LTBI before anti-TNF agents treatment.54 During the anti-TNF therapy, the patients should also be closely monitored at least once a year to identify reactivation of latent TB or new TB infection. Patients' adherence to isoniazid (INH) treatment is important for preventing the reactivation of latent TB. Screening and surveillance may be of particular importance when TNF-α antagonists are used as part of combined therapies. A previously published systematic review55 reported that, compared with monotherapy, the risk of TB was increased 13-fold when anti-TNF agents were combined with immunosuppressant agents such as methotrexate or azathioprine. Additionally, a recent network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview highlighted the association between different biologics including TNF-α antagonists and higher rates of adverse effects in several diseases. These adverse events included TB reactivation, although the roles of other factors potentially associated with TB reactivation were not fully illuminated.13

Several limitations in this study should be addressed. First, the review identified only a limited number of RCTs, with only two studies about golimumab and one about etanercept. Second, the relatively short follow-up period in the RCTs might have caused an underestimation of TB incidence rates. Third, the meta-analysis was limited to published scientific publications, and the omission of unpublished data from pharmaceutical trials may affect the pooled results.

In summary, our results suggest that the risk of TB is doubled when patients with any condition are treated with anti-TNF-α drugs. When anti-TNF-α treatments are considered, the increased risk of TB should be part of the treatment decision-making process. Patients should be screened for LTBI and anti-TB prophylaxis or concomitant treatment should be considered. Further high-quality research regarding the long-term safety of biologics is needed to improve the safety of biological treatment in clinical use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the authors of the primary studies and Dr Brian Buckley (Visiting Professor, Wuhan University) for assistance in preparation of the English language manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors conceived of and designed the study. ZZ and WF performed the literature search, data collection and statistical analysis. GY and ZX assessed the quality of articles. ZZ, JW and QC wrote the paper. MY and WF revised the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81472033 and 30901308), the National Science Foundation of Hubei Province (nos. 2013CFB233 and 2013CFB235), the Scientific and Technological Project of Wuhan City (2014060101010045), Hubei Province Health and Family Planning Scientific Research Project (WJ2015Q021) and Seeding Program of the Science and Technology Innovation from Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (ZNPY2016054).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bradley JR. TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J Pathol 2008;214:149–60. 10.1002/path.2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choy EH, Panayi GS. Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:907–16. 10.1056/NEJM200103223441207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baraliakos X, Listing J, Fritz C et al. . Persistent clinical efficacy and safety of infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis after 8 years—early clinical response predicts long-term outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1690–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrier C, Rutgeerts P. Cytokine blockade in inflammatory bowel diseases. Immunotherapy 2011;3:1341–52. 10.2217/imt.11.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansback N, Sizto S, Sun H et al. . Efficacy of systemic treatments for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatology (Basel) 2009;219:209–18. 10.1159/000233234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sánchez-Moya AI, García-Doval I, Carretero G et al. . Latent tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis in patients with psoriasis: a study on the incidence of tuberculosis and the prevalence of latent tuberculosis disease in patients with moderate-severe psoriasis in Spain. BIOBADADERM registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:1366–74. 10.1111/jdv.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu M, Zhou X, Niu L et al. . Targeting transmembrane TNF-alpha suppresses breast cancer growth. Cancer Res 2013;73:4061–74. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solovic I, Sester M, Gomez-Reino JJ et al. . The risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1185–206. 10.1183/09031936.00028510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raval A, Akhavan-Toyserkani G, Brinker A et al. . Brief communication: characteristics of spontaneous cases of tuberculosis associated with infliximab. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:699–702. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ai JW, Zhang S, Ruan QL et al. . The risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist: a meta-analysis of both randomized controlled trials and registry/cohort studies. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2229–37. 10.3899/jrheum.150057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souto A, Maneiro JR, Salgado E et al. . Risk of tuberculosis in patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases treated with biologics and tofacitinib: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and long-term extension studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1872–85. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X, Chen J, Peng Y et al. . [Meta-analysis of infection risks of anti-TNF-alpha treatment in rheumatoid arthritis]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2013;38:722–36. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R et al. . Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(2):Cd008794 10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H-Y, Lee S-K, Song YW et al. . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of the human anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody adalimumab administered as subcutaneous injections in Korean rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate. APLAR J Rheumatol 2007;10:9–16. 10.1111/j.1479-8077.2007.00248.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG et al. . Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2462–76. 10.1056/NEJMoa050516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baranauskaite A, Raffayová H, Kungurov NV et al. . Infliximab plus methotrexate is superior to methotrexate alone in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis in methotrexate-naive patients: the RESPOND study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:541–8. 10.1136/ard.2011.152223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker J, Hoffmann M, Wozel G et al. . Efficacy and safety of infliximab vs. methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of an open-label, active-controlled, randomized trial (RESTORE1). Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1109–17. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J et al. . Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 2002;359:1187–93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08215-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF et al. . The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen DY, Chou SJ, Hsieh TY et al. . Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, comparative study of human anti-TNF antibody adalimumab in combination with methotrexate and methotrexate alone in Taiwanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. J Formos Med Assoc 2009;108:310–19. 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60071-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W et al. . Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1383–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Couriel DR, Saliba R, de Lima M et al. . A phase III study of infliximab and corticosteroids for the initial treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15:1555–62. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U et al. . Safety and efficacy of ustekinumab or golimumab in patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1296–307. 10.1183/09031936.00000914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann RM, Emery P et al. . Clinical, functional and radiographic consequences of achieving stable low disease activity and remission with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone in early rheumatoid arthritis: 26-week results from the randomised, controlled OPTIMA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:64–71. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy WP, Simon JA, Offutt C et al. . Efficacy and safety of pateclizumab (anti-lymphotoxin-alpha) compared to adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: a head-to-head phase 2 randomized controlled study (The ALTARA Study). Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16:467 10.1186/s13075-014-0467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT et al. . Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1400–11. 10.1002/art.20217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keystone E, Heijde Dv, Mason D Jr et al. . Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3319–29. 10.1002/art.23964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maini R, St Clair EW, Breedveld F et al. . Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet 1999;354:1932–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05246-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EM et al. . Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:75–85. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reich K, Ortonne JP, Gottlieb AB et al. . Successful treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with the PEGylated Fab’ certolizumab pegol: results of a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a re-treatment extension. Br J Dermatol 2012;167:180–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R et al. . Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two-year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:86–94. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C et al. . Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1096–103. 10.1136/ard.2007.080002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieper J, Lenaerts J, Wollenhaupt J et al. . Efficacy and safety of infliximab plus naproxen versus naproxen alone in patients with early, active axial spondyloarthritis: results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled INFAST study, Part 1. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:101–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen J, Landewé RB, Mease P et al. . Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. A randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:797–804. 10.1136/ard.2008.101659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS et al. . Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3432–43. 10.1002/art.20568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki Y, Motoya S, Hanai H et al. . Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol 2014;49:283–94. 10.1007/s00535-013-0922-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tam LS, Shang Q, Li EK et al. . Infliximab is associated with improvement in arterial stiffness in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis—a randomized trial. J Rheumatol 2012;39:2267–75. 10.3899/jrheum.120541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Den Bosch F, Kruithof E, Baeten D et al. . Randomized double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha (infliximab) versus placebo in active spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:755–65. 10.1002/art.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewé R et al. . Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression′ with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3928–39. 10.1002/art.23141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Vollenhoven RF, Kinnman N, Vincent E et al. . Atacicept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1782–92. 10.1002/art.30372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenzel SE, Barnes PJ, Bleecker ER et al. . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade in severe persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:549–58. 10.1164/rccm.200809-1512OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westhovens R, Yocum D, Han J et al. . The safety of infliximab, combined with background treatments, among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and various comorbidities: a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1075–86. 10.1002/art.21734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmona L, Hernández-García C, Vadillo C et al. . Increased risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1436–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR et al. . Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2287–93. 10.1002/art.10524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arkema EV, Jonsson J, Baecklund E et al. . Are patients with rheumatoid arthritis still at an increased risk of tuberculosis and what is the role of biological treatments? Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1212–17. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekker LG, Freeman S, Murray PJ et al. . TNFα controls intracellular mycobacterial growth by both inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent and inducible nitric oxide synthase-independent pathways. J Immunol 2001;166:6728–34. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kindler V, Sappino AP, Grau GE et al. . The inducing role of tumor necrosis factor in the development of bactericidal granulomas during BCG infection. Cell 1989;56:731–40. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90676-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murdaca G, Spanò F, Contatore M et al. . Infection risk associated with anti-TNF-alpha agents: a review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2015;14:571–82. 10.1517/14740338.2015.1009036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Danielsen AV, Fløe A, Lillebaek T et al. . An interferon-gamma release assay test performs well in routine screening for tuberculosis. Dan Med J 2014;61:A4856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carmona L, Gómez-Reino JJ, Rodríguez-Valverde V et al. . Effectiveness of recommendations to prevent reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1766–72. 10.1002/art.21043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yun JW, Lim SY, Suh GY et al. . Diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in arthritis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2007;22:779–83. 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.5.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hauck FR, Neese BH, Panchal AS et al. . Identification and management of latent tuberculosis infection. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:879–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorenzetti R, Zullo A, Ridola L et al. . Higher risk of tuberculosis reactivation when anti-TNF is combined with immunosuppressive agents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med 2014;46:547–54. 10.3109/07853890.2014.941919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012567supp_appendices.pdf (966.7KB, pdf)