Salicylic acid stimulates succinate dehydrogenase activity and induces mitochondrial ROS production to induce stress signaling.

Abstract

Mitochondria are known for their role in ATP production and generation of reactive oxygen species, but little is known about the mechanism of their early involvement in plant stress signaling. The role of mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in salicylic acid (SA) signaling was analyzed using two mutants: disrupted in stress response1 (dsr1), which is a point mutation in SDH1 identified in a loss of SA signaling screen, and a knockdown mutant (sdhaf2) for SDH assembly factor 2 that is required for FAD insertion into SDH1. Both mutants showed strongly decreased SA-inducible stress promoter responses and low SDH maximum capacity compared to wild type, while dsr1 also showed low succinate affinity, low catalytic efficiency, and increased resistance to SDH competitive inhibitors. The SA-induced promoter responses could be partially rescued in sdhaf2, but not in dsr1, by supplementing the plant growth media with succinate. Kinetic characterization showed that low concentrations of either SA or ubiquinone binding site inhibitors increased SDH activity and induced mitochondrial H2O2 production. Both dsr1 and sdhaf2 showed lower rates of SA-dependent H2O2 production in vitro in line with their low SA-dependent stress signaling responses in vivo. This provides quantitative and kinetic evidence that SA acts at or near the ubiquinone binding site of SDH to stimulate activity and contributes to plant stress signaling by increased rates of mitochondrial H2O2 production, leading to part of the SA-dependent transcriptional response in plant cells.

Within the mitochondrial electron transport chain, complex II (succinate dehydrogenase [SDH]) oxidizes succinate to fumarate by transferring electrons to ubiquinone (UQ), which is reduced to ubiquinol. The enzyme is formed by four subunits: a flavoprotein (SDH1), which contains the FAD cofactor, an iron sulfur (Fe-S) protein (SDH2) housing three Fe-S clusters, and two small integral membrane proteins (SDH3 and SDH4), anchoring the enzyme to the inner membrane and forming the UQ binding site (Huang and Millar, 2013; Lemire and Oyedotun, 2002; Sun et al., 2005). Several assembly factors have been identified that facilitate FAD and Fe-S insertion into SDH subunits (Ghezzi et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2009) and one of these, SDHAF2, has been characterized in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Huang et al., 2013).

Complex I and III have been long considered to be the major sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production inside mitochondria (mtROS), but recent studies in both mammals and plants have demonstrated that complex II can also be a significant source of mtROS (Jardim-Messeder et al., 2015; Quinlan et al., 2012). In mammals, complex II influences reperfusion injury through mtROS production via reverse electron transport after succinate accumulation (Chouchani et al., 2014). However, the relative importance of mtROS generated from complex II in plants has been unclear, and knockout of the SDH complex or its assembly factors in plants is lethal, largely preventing its direct study through gene deletion in plants (Huang et al., 2013; León et al., 2007). This limitation changed when a point mutation of SDH1-1 (dsr1) was identified that did not knockout SDH, but instead lowered SDH activity and decreased mitochondrial ROS production. It was first identified as a mutant that had lost salicylic acid (SA)- but not H2O2-dependent stress response using a GST GSTF8 promoter stress response assay (Gleason et al., 2011). The dsr1 mutant showed steady-state decrease expression of peroxidases, glutaredoxins, and trypsin and protease inhibitor family genes and reduced expression on SA induction of a set of SA-responsive genes normally induced in response to exposure of Arabidopsis to bacterial, fungal, or viral pathogens (Gleason et al., 2011). The dsr1 mutant also had higher susceptibility to fungal and bacterial pathogens, indicating that mitochondrial SDH is involved in response to biotic stress in vivo in plants. However, despite this evidence for the involvement of a mutated SDH1 and recovery of signaling when wild-type SDH1 was overexpressed (Gleason et al., 2011), it was still unclear how a mutation in SDH such as dsr1 could affect mitochondrial ROS production and the downstream stress response induced by SA.

SA acts as a hormone in plant processes like thermogenesis (Raskin et al., 1987), ethylene synthesis, and fruit ripening (Leslie and Romani, 1988), but it also acts as a stress regulator during plant defense response (Rao and Davis, 1999; Senaratna et al., 2000; Yalpani et al., 1991). Accumulation of SA is often correlated with an increase in ROS production during plant stress response (for review, see Herrera-Vásquez et al., 2015). A series of SA binding proteins has been identified, notably catalase (Chen et al., 1993a), peroxidase (Durner and Klessig, 1995), and methyl-salicylate esterase (Forouhar et al., 2005) that appear to explain this correlation, but their roles as general SA receptors have been controversial (Attaran et al., 2009; Bi et al., 1995). Further sets of SA binding proteins in Arabidopsis have been identified by affinity screens and include several mitochondrial enzymes and also GSTs including GSTF8, which showed enzymatic inhibition by SA (Manohar et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2012). However, as these enzymes are not classical transcription regulators, they are unlikely to directly regulate gene expression. Recently, there is clear evidence for NON-EXPRESSOR OF PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENES1 (NPR1), NPR3, and NPR4 acting together as SA receptors based on their binding properties, direct role in defense gene expression, and their impact on disease resistance (Fu et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012). However, studies beyond defense responses have shown an involvement of SA in thermotolerance and drought resistance combined with an induction of mitochondrial ROS production (Nie et al., 2015; Okuma et al., 2014). SA at high concentration is also reported to act as an inhibitor of respiration in isolated mitochondria, but applied in lower concentrations it has been shown to stimulate the respiration rate of whole-cell tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) culture (Norman et al., 2004). This indicates the importance of kinetic analysis at an enzymatic level to uncover the role of SA in respiratory responses in plants.

To define the role of SDH in this SA signaling process, we utilized two Arabidopsis mutant lines that have decreased SDH1 function. The fortuitous dsr1 point mutation acts directly to reduce SDH1 function, while knockdown of an SDH assembly factor (sdhaf2) acts indirectly to limit the amount of functional SDH1. We show that both mutants decrease SA-dependent promoter activity in vivo, with dsr1 more effective than sdhaf2. Kinetic analysis of SDH activity in these lines showed that while both mutants had reduced maximum capacity, dsr1 also differed in succinate affinity and enzymatic efficiency. To determine the nature of the effect of SA and its interaction with SDH for stress signaling, we measured the change in SDH activity in isolated mitochondria in the presence of different concentrations of SA. We observed an SA-dependent increase of SDH activity in the presence of micromolar SA concentrations but only when succinate-dependent electron transport was directed through the UQ binding site of SDH, increasing the succinate:quinone reductase (SQR) activity. We show that succinate-dependent mtROS production increased significantly after the addition of SA in wild type, but less so in dsr1 and sdhaf2. In vivo, we showed that blocking SA-induced promoter activity could be partially relieved in sdhaf2 by addition of exogenous succinate, but this was not possible with dsr1, consistent with our analysis of the differing SDH kinetics in the two mutant lines. Together, this provides quantitative and kinetic evidence for a direct involvement of SA in a SDH-dependent signaling pathway in plants that involves mitochondrial ROS production.

RESULTS

Altered Stress Promoter Response to Stress in dsr1 and sdhaf2

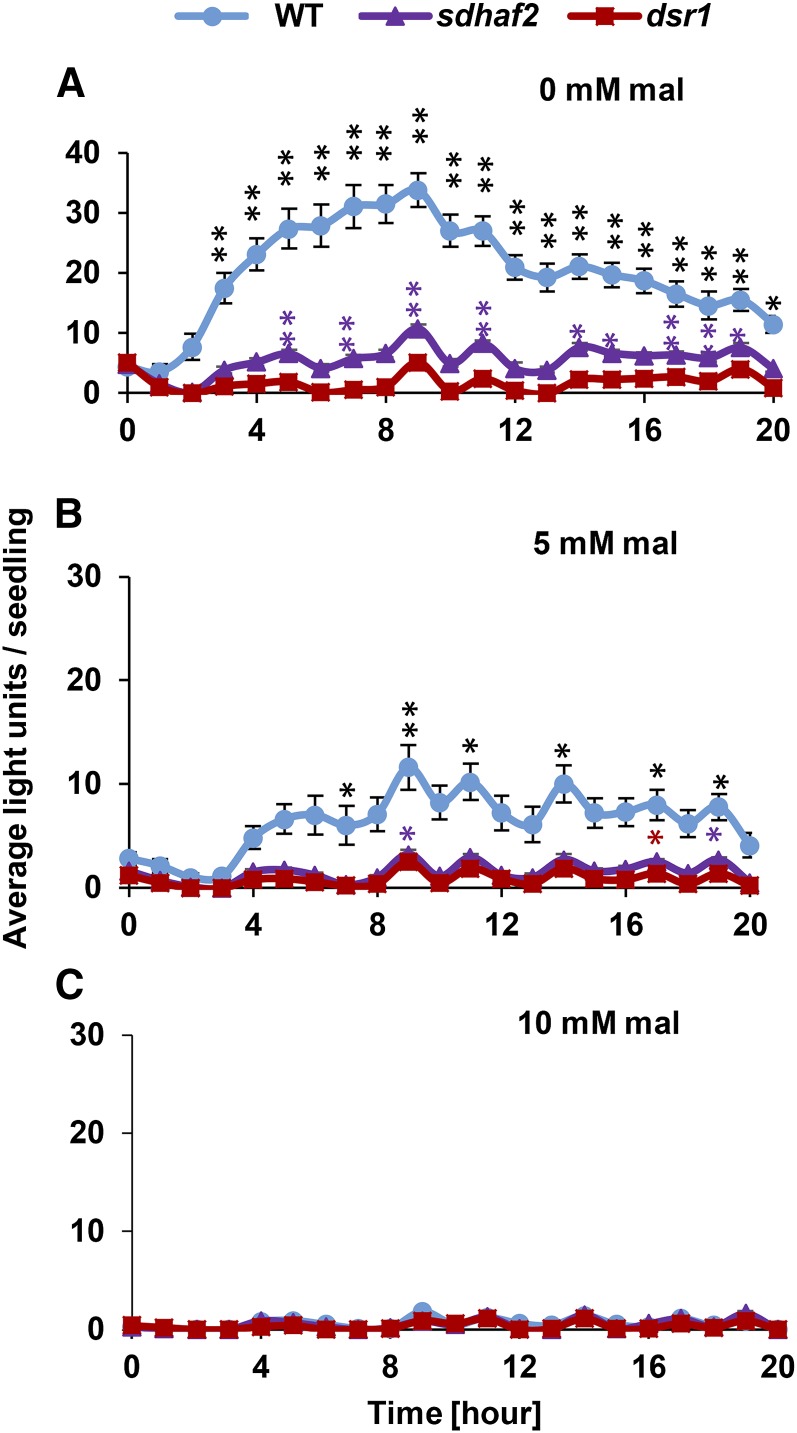

We previously identified a mutant (dsr1), carrying a single SDH1-1 point mutation, and demonstrated a disruption in SA-induced promoter activity in these plants using a GSTF8 promoter-driven LUC reporter assay (Gleason et al., 2011). While this effect was linked to SDH1 through a complementation assay, it could not be independently confirmed with knockout plants, because loss of SDH1 is embryo lethal in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2013; León et al., 2007). To independently investigate the link between SDH and SA-induced GSTF8 response, we therefore crossed an SDH assembly factor knockdown line, sdhaf2, that has lower SDH activity (Huang et al., 2013) with Col-0 containing the GSTF8:luciferase (GSTF8:luc) reporter gene (JC66, referred to as wild type in this manuscript; Gleason et al. (2011). We then treated both mutant lines (dsr1 and sdhaf2) with SA to compare stress promoter response of 4-d-old seedlings (Fig. 1A, at 7 mm SA; Supplemental Fig. S1, at 1 mm SA). Both mutants showed low or no responses to the treatment compared to wild type (ANOVA P ≤ 0.01); however, unlike dsr1, sdhaf2 showed significant LUC expression above untreated samples at some time points in the 20-h period following SA application (Fig. 1A, posthoc pairwise test). This strengthened our previous evidence for SDH being involved in SA signaling and showed the effect was independent of the specific amino acid mutation in dsr1 (Gleason et al., 2011). Both dsr1 and sdhaf2 showed a significant LUC expression following H2O2 treatment that was not significantly different from wild type (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

GSTF8:luc induction in sdhaf2 and dsr1 after SA treatment compared to wild type. Average of total fluorescence signal generated by each seedling (n = 10) per hour after treatment of 7 mm SA in the presence of 0 mm (A), 5 mm (B), and 10 mm (C) malonate (mal) in the growth media. Two-factor ANOVA between genotypes (P ≤ 0.01), posthoc Tukey test comparing signal induction to time point zero within genotype *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

To further confirm that this signaling pathway was SDH dependent, the SDH inhibitor malonate was added in concentrations of 5 and 10 mm to the growth media, and GSTF8 promoter response was measured after SA treatment. No change in seedling growth and development could be observed in the presence of malonate over a period of 4 d. However, 5 mm malonate could significantly reduce the signal responses in wild type and sdhaf2 (ANOVA P ≤ 0.01), but the induction of SA signaling in wild type was still possible (Fig. 1B, posthoc pairwise test). At 10 mm, malonate inhibited the LUC promoter response almost to zero in all genotypes (Fig. 1C). The reduction of stress promoter response that we observed in both SDH mutant lines and the further inhibition of SDH by treatment with malonate in wild type indicate that the degree of function of the SDH enzyme can titrate the degree of stress signaling via this pathway.

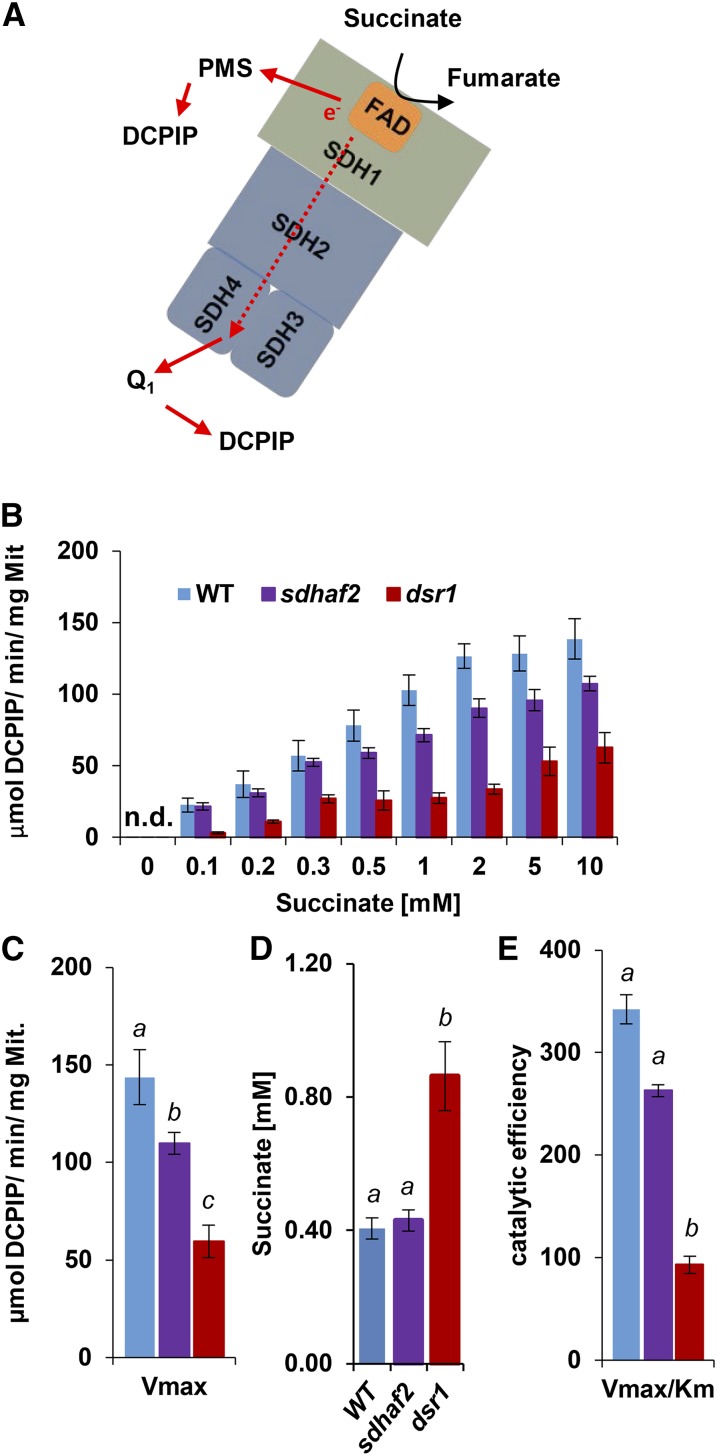

Catalytic Efficiency of SDH Is Significantly Lower in dsr1

To further characterize the GSTF8 promoter response in dsr1, sdhaf2, and wild type, we investigated the kinetics of SDH activity in these lines using phenazine methosulfate (PMS) and dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP; Fig. 2A). We isolated mitochondria from each line and compared the SDH enzymatic catalytic efficiency and substrate affinity using Michaelis-Menten kinetics and Brooks Kinetic Software (Brooks, 1992). To calculate the Km of succinate, a series of succinate concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 10 mm were used for SDH activity measurements (Fig. 2B). Comparing the activity between genotypes over the range of different succinate concentrations, sdhaf2 and wild type shared a similar trend (ANOVA P = 0.1), but dsr1 showed significantly lower activity than wild type and sdhaf2 (ANOVA P < 0.01), even when a high concentration of succinate was applied, demonstrating a probable difference in succinate affinity between the two mutants. Looking at the maximum velocity, measured at saturating concentration of succinate (10 mm), there was a significant distinction in both mutant lines compared to wild type (Fig. 2C). It should be noted that in the case of sdhaf2, the lower amount of the SDH enzyme (one-half compared to wild type) is responsible for the lower activity rate per mg mitochondria (Huang et al., 2013), whereas in dsr1 the same amount of SDH enzyme as wild type is present in mitochondria (Gleason et al., 2011). Calculation of the Km value of succinate (Fig. 2D) showed that dsr1 had a significantly higher Km than wild type and sdhaf2. A concentration slightly >0.4 mm of succinate was required to reach one-half maximum velocity in wild type and sdhaf2, but over twice as much substrate concentration was needed for dsr1 (0.86 mm). The catalytic efficiency (Vmax/Km), which represents the enzymatic efficiency at low concentrations of substrate, was ∼3-fold lower in dsr1 compared to wild type and sdhaf2 (Fig. 2E), showing that dsr1 was kinetically distinguishable from sdhaf2.

Figure 2.

Lower succinate affinity and catalytic efficiency in dsr1. Concentrations of 0.1 to 10 mm of succinate were used to calculate maximal SDH activity, measured as absorbance change of DCPIP at 600 nm. Km was calculated using Hanes-Plot and Brook Kinetics Software. A, Scheme of SDH showing electron transfer from succinate to UQ binding site. B, Correlation of SDH activity and succinate concentrations of the wild type, sdhaf2, and dsr1. C, Maximal enzyme velocity (Vmax). D, Calculated Km of succinate using Brooks kinetic software. E, enzymatic efficiency (Vmax/Km) for sdhaf2 and dsr1. se of six biological replicates. Two-factor ANOVA comparing SDH activity between genotypes (B) P ≤ 0.01 (dsr1 compared to the wild type and sdhaf2). Single-factor ANOVA comparing catalytic efficiency and succinate affinity (D and E) between genotypes. Different letters indicate significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between genotypes. n.d., Not detected.

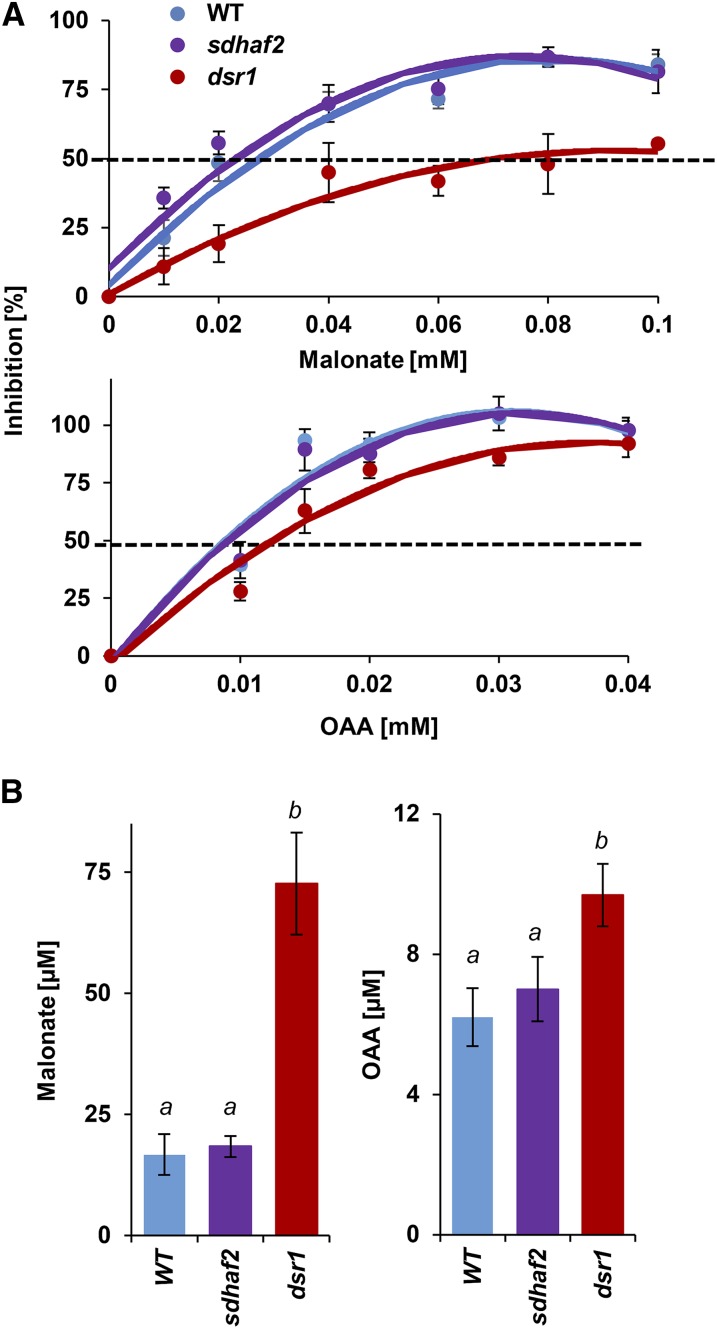

dsr1 Shows Lower Affinity to the Competitive Inhibitors Malonate and OAA

The changes in SDH kinetics observed in dsr1 were most likely caused by the point mutation that occurs in the substrate binding site. To further prove that this causes a change in the binding affinity, the competitive inhibitor malonate together with a low concentration (Km value) of succinate were added to isolated mitochondria from each genotype and SDH activity was measured. Because of the low catalytic efficiency of dsr1, twice as much succinate was used in the assay to reach one-half maximum velocity (0.5 mm for the wild type and sdhaf2; 1 mm for dsr1). Using malonate concentrations in a range from 10 to 100 µm (Fig. 3A, top), inhibition of SDH activity was calculated to determine the IC50 value for malonate. The inhibition in dsr1 has less effect on enzyme activity when compared to wild type and sdhaf2, showing that a higher concentration of inhibitor is necessary to inhibit SDH in dsr1. An IC50 value of ∼70 µm of malonate was determined for dsr1 compared to a IC50 of ∼20 µm for wild type and sdhaf2 (Fig. 3B). To confirm that the changes in malonate inhibition were independent of the higher concentration of succinate used in the assay for dsr1, the assay was repeated with a saturating (5 mm) concentration of substrate (Supplemental Fig. S2A). A significant inhibition in wild type and sdhaf2 could be reached using 0.1 (wild type) and 0.5 mm (sdhaf2) malonate. But for dsr1, no significant inhibition was caused, and SDH was not significantly inhibited even when a concentration of 1 mm was applied. A significantly higher IC50 of ∼0.4 mm was calculated for dsr1 compared to ∼0.2 mm for sdhaf2 and wild type (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Based on these kinetic results, we hypothesized that other succinate competitive inhibitors would also show a lower binding affinity in dsr1. We applied a second, physiologically more relevant competitive inhibitor, oxaloacetic acid (OAA), together with the same succinate concentrations used in the malonate assay (Fig. 3A, bottom) to isolated mitochondria. A significantly higher IC50 of 9.6 µm of OAA for dsr1 compared to 7 µm and 6.2 µm for sdhaf2 and wild type was calculated (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

IC50 of SDH competitive inhibitors malonate and oxaloacetate are higher in dsr1. Inhibition of SDH was measured using increasing amounts of malonate and OAA together with the Km concentration of succinate (0.5 mm for wild type and sdhaf2; 1 mm for dsr1). IC50 was calculated using Brooks Kinetic Software. A, Percentage inhibition of SDH activity in the presence of malonate and OAA. B, Calculated IC50 of malonate (left) and OAA (right). se of four biological replicates. Single-factor ANOVA comparing IC50 between genotypes. Different letters indicate significant differences, P ≤ 0.07.

Together, these findings demonstrated that the single point mutation in dsr1 changed the kinetics of SDH and led to a lower binding affinity for the substrate succinate, which results in a lower catalytic efficiency as well as a lower affinity for the competitive inhibitors malonate and OAA. This is a clear distinction to the knockdown line sdhaf2, which has reduced SDH1-1 content (Huang et al., 2013) but does not show any kinetic alterations compared to wild type (Figs. 2 and 3).

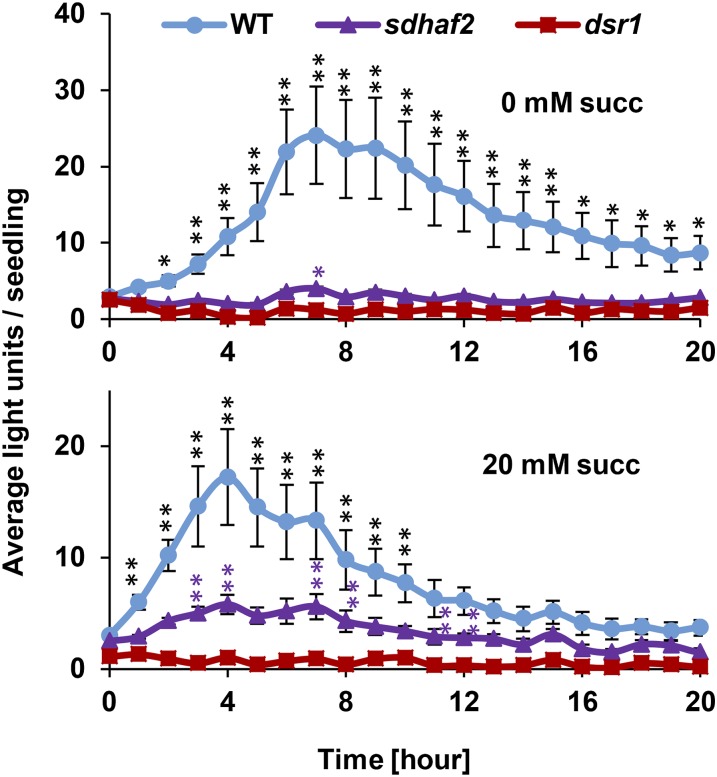

High Concentrations of Succinate Stimulate Stress Promoter Response in sdhaf2 But Not in dsr1

Because our data showed that dsr1 has a low affinity for succinate compared to sdhaf2 and wild type (Fig. 2, C–E), we investigated if succinate itself would enhance SA-induced signaling. We repeated the GSTF8:luc assay with 20 mm succinate added to the growth media. No significant induction of promoter activity could be measured in dsr1 when succinate was present (Fig. 4, bottom), presumably due to its very low catalytic efficiency. However, the promoter activity in sdhaf2 was significantly induced within 3 h after the SA treatment in the presence of added succinate (Fig. 4, bottom, posthoc pairwise test). Because sdhaf2 shares the same SDH kinetic features as wild type, we hypothesized a higher amount of succinate might induce a higher signal response in wild type; however, the signal was apparently already saturated by the higher SDH enzymatic activity. Nevertheless, we observed a shift in signal response in wild type, leading to an earlier peak of signal induction. Higher amounts of succinate might not further increase the signal in the wild type but could possibly cause a faster response that also declines more rapidly compared to no additional succinate (Fig. 4, bottom).

Figure 4.

SA-induced GSTF8 signal can be rescued in sdhaf2 using high concentrations of succinate. Average of total fluorescence signal generated by each seedling (n = 10) per hour after treatment of 7 mm SA in the presence of 0 (top) and 20 mm succinate (succ, bottom) in the growth media. Error bars: se, posthoc Tukey test comparing signal induction to time point zero within genotype, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01.

Low Concentrations of SA Increase SQR Activity

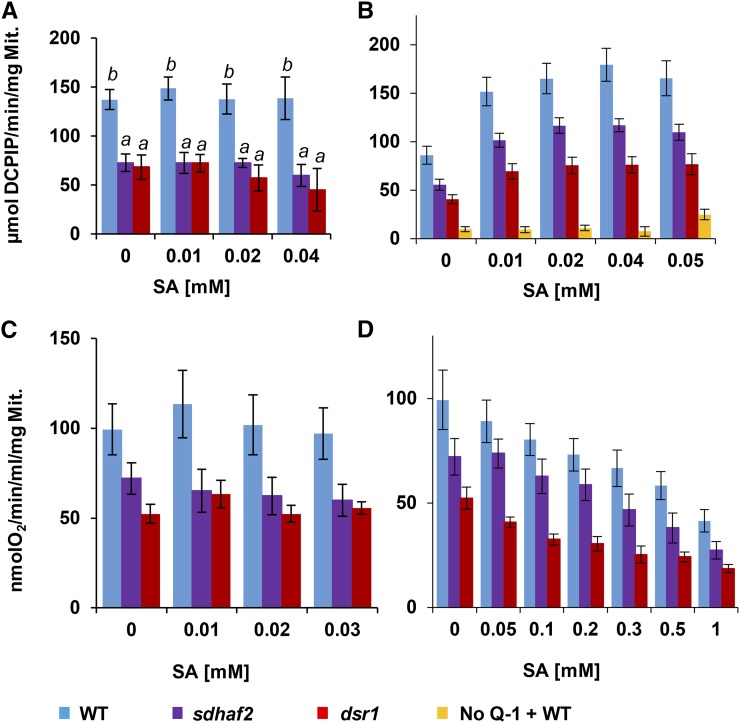

To investigate the role of SA and its interaction with SDH during stress signaling, SQR activity in the presence of SA (10–50 µm) was measured in isolated mitochondria using different electron acceptors. No significant effect of SA was observed for measurements of succinate-dependent DCPIP reduction in the presence of PMS that enables direct acceptance of electrons from the flavin in SDH1 (Figs. 2A and 5A). However, within SDH, electrons are normally transferred from the succinate binding site in SDH1, through SDH2, and finally to the UQ binding site in the membrane. When the assay was repeated, measuring electron transfer to coenzyme Q1 and then to DCPIP (Fig. 2A), a significant increase in SQR activity was observed in the presence of SA (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S3A; Supplemental Table S1). This suggested that the interaction of complex II with SA occurred not at the succinate binding site, but along the electron transfer to UQ or even directly at the UQ binding site. For both mutant lines, a significant increase in electron flow could be measured following SA addition (Supplemental Fig. S3A; Supplemental Table S1), but their overall activity response was lower compared to wild type (ANOVA P < 0.05). dsr1 showed the lowest SA-induced activity, significantly distinguishable from both sdhaf2 (ANOVA P = 0.04) and the wild type (ANOVA P < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Low concentrations of SA increase SQR activity. A, SDH activity measured at the succinate binding site (PMS + DCPIP) in the presence of SA. B, SQR activity measured at UQ binding site (Q1 [80 µm] + DCPIP) in the presence of SA. As a negative control, activity was measured in the absence of Q1 in wild-type mitochondria (yellow bars). In both cases, SDH activity was measured in µmol DCPIP/min/mg Mit. in the presence of 5 mm succinate and SA concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.05 mm. C and D, Succinate-dependent oxygen consumption was measured using a Clark type oxygen electrode in the presence of 5 mm succinate and SA concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 1 mm. Fisher’s lsd test was used to determine differences (different letters indicate significant differences; for P values and letter distribution, see Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Fig. S3); P ≤ 0.05.

Previous studies suggested complex III contained a potential SA binding protein (Nie et al., 2015) and showed inhibition of complex III activity in the presence of 0.1 and 0.5 mm SA. To confirm whether complex III activity would be affected by SA, we performed an activity assay using cytochrome c (cyt c) and ubiquinol-10 as substrates and added SA concentrations from 0.01 to 1 mm to the assay (Supplemental Fig. S4). Enzyme activity was determined spectrophotometrically, following the reduction of cyt c. In our hands, no significant differences could be observed in either the genotypes or the response to the SA treatment (Supplemental Fig. S4), confirming that the SA effect observed in this study is complex II dependent (Fig. 5B).

To further investigate the hypothesis that SA interacts with SDH at the UQ site, compounds known to bind to the UQ site (thenoyltrifluoroacetone (TTFA), carboxin) were added at similar concentrations to SA (Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). SQR activity showed a significant increase in wild type in the presence of TTFA, and a similar trend was observed in carboxin treatment. Both TTFA and carboxin are commercial complex II inhibitors with a reported IC50 of 5.8 µm and 1.1 µm in mammals (Miyadera et al., 2003). Nevertheless, using wild-type Arabidopsis, in our hands, low concentrations of these inhibitors appear to stimulate significantly the electron flow to UQ in a similar manner and at similar concentrations to SA, leading to a faster reduction of DCPIP and a higher SQR activity. Inhibition in Arabidopsis mitochondria was achieved using concentrations of 1 mm TTFA/carboxin (Supplemental Fig. S5), consistent with other reports in Arabidopsis (Jardim-Messeder et al., 2015; León et al., 2007).

To determine if this increased electron transfer to Q1 in the presence of low concentrations of SA would also be observed via UQ to O2 in intact mitochondrial electron transport, isolated mitochondria of sdhaf2 and dsr1 were treated with SA in the presence of 5 mm succinate, and oxygen uptake was measured using a Clark type oxygen electrode. No significant changes in respiration rate across the lines could be observed after adding low concentrations of SA (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. S3B; Supplemental Table S1). Using higher concentrations of SA (0.1–1 mm), a gradual inhibition of respiration rate could be observed (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. S3B; Supplemental Table S1), which is consistent with previous studies (Norman et al., 2004). This suggested that enhanced electron transfer from the UQ site to DCPIP in the presence of SA is not observed to significantly increase total respiratory rate in isolated mitochondria ending in the respiratory oxidases.

To test whether other ETC complexes were affected in these genotypes, O2 uptake in the presence of SA was measured using the substrates NADH, and malate with Glu (Supplemental Fig. S6A). All genotypes showed sufficient oxygen consumption with these substrates, and no significant differences were observed between the mutants and wild type. Also, no inhibitory effect of SA was observed with either substrate. This confirmed that the decrease in basal respiration observed in dsr1 and sdhaf2 (Fig. 5, C and D) was specific to succinate and complex II.

Low Concentrations of SA Induce Mitochondrial H2O2 Production

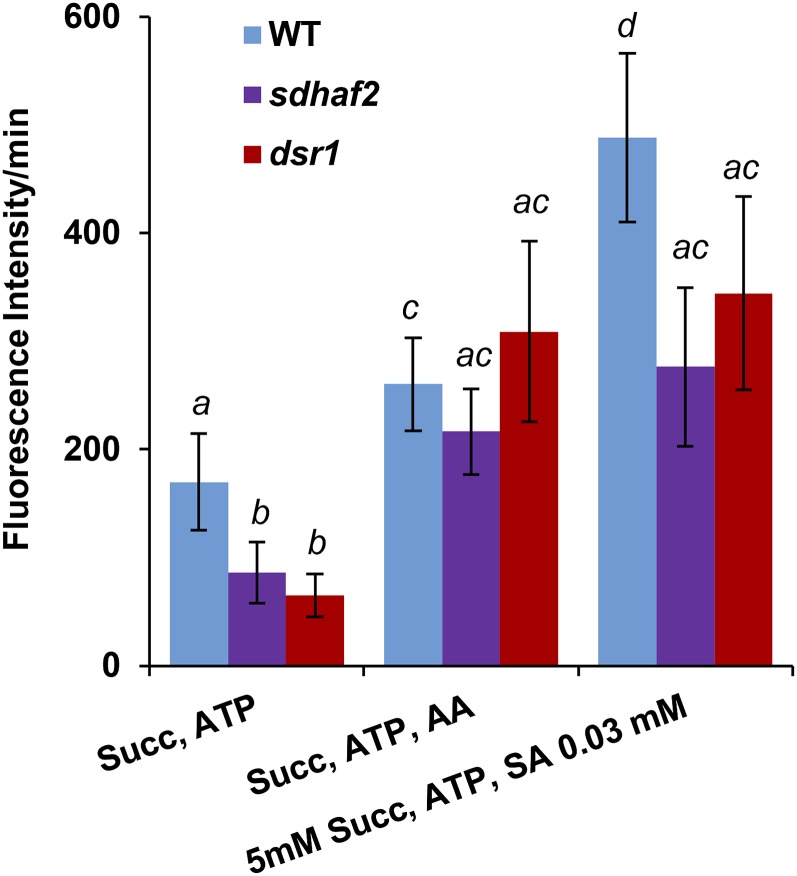

While respiration rate was not affected by low concentrations of SA, another possibility was that leakage of electrons occurs at the UQ site, which would result in partial reduction of oxygen and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as O2− and H2O2. As ROS production is typically only 3% to 4% of the total respiratory rate, we might not expect to see these changes by monitoring total O2 consumption (Andreyev et al., 2005; Kudin et al., 2004). To test this hypothesis, freshly isolated mitochondria from plants were treated with SA (0.03 mm) in the presence of 5 mm succinate and 0.5 mm ATP (Fig. 6). We measured succinate-dependent mitochondrial H2O2 production using the fluorescent dye 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA; Fig. 6). O2− has a short lifetime and is a highly reactive molecule that is rapidly converted into H2O2. H2O2 is able to leave the mitochondrion (Bienert et al., 2007; Henzler and Steudle, 2000); therefore, the resulting reactive oxygen species that are measured using DCFDA can be assumed to be H2O2. To determine the basal rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production, 5 mm succinate and 0.5 mm ATP were added to isolated mitochondria. To determine if any background fluorescence signal occurred, negative controls for all assays were used (Supplemental Fig. S7). These controls showed that a background signal did occur with just mitochondria and in the absence of respiratory substrate in the sample (Supplemental Fig. S7). Adding SA in the absence of respiratory substrate to these samples increased the signal significantly, giving the impression of a high ROS induction, but the actual difference in signal intensity between the plus and minus succinate samples shows that only a small fraction of this signal is succinate dependent (Supplemental Fig. S7). This fraction was taken as the actual succinate-dependent H2O2 production value in our measurements (Fig. 6). Both dsr1 and sdhaf2 lines have a lower basal rate of H2O2 production when compared with wild type (Fig. 6). Antimycin A (AA) was used as a positive control, as it is known to induce production of H2O2 (Dröse and Brandt, 2008), and we observed a significant increase in H2O2 generation when AA was added to mitochondria from all genotypes. To investigate the SA effect on H2O2 production, 0.03 mm SA together with succinate and ATP were added to mitochondria. Adding SA caused a significant induction in H2O2 production compared to the basal rate (Fig. 6), but the overall rate of H2O2 production was still lower in both mutant lines, which showed no significant difference in SA induction compared to the AA treatment.

Figure 6.

mtH2O2 production is lower in dsr1 and sdhaf2. mtH2O2 production was measured using DCFDA with excitation/emission wavelengths of 490/520 nm. Succinate (5 mm), 0.5 mm ATP, 5 µm AA, and 0.03 mm SA were added to freshly isolated mitochondria immediately before the measurement. Fluorescence intensity was measured over 10 min and the rate of fluorescence/min was calculated. se of eight biological replicates. Wilcoxon signed rank test between genotypes, different letters indicate significant differences, P ≤ 0.05.

To test whether other ETC complexes could be a source of SA-stimulated ROS production, as was reported in previous studies (Nie et al., 2015), we measured H2O2 production in the presence of NADH and malate together with Glu (Supplemental Fig. S6B). In our hands, we did not observe any significant ROS production above the background signal without any substrates, as well as no differences between genotypes. Nie et al. (2015) did not use controls in their experiments to show the effects observed were dependent on the presence of respiratory substrates. Their measured signals and SA responses may come from background reactions independent of an active respiratory system inside mitochondria.

DISCUSSION

SDH-Deficient Plants Show Altered SA-Dependent Signaling Responses

In plants, GSTs are induced by SA, ROS (H2O2), and biotic/abiotic stresses (Moons, 2005), and GSTF8 is a well-described representative marker for early stress/defense gene induction (Chen et al., 1996; Sappl et al., 2009). In this study, we show that the lack of induction of GSTF8:luc by SA in dsr1 (Gleason et al., 2011) can be mimicked by reduced FAD insertion and assembly of SDH1-1 through knockdown of the SDH assembly factor SDHAF2. This strengthens the hypothesis that quantitative changes in SDH function are required for at least one pathway of SA-induced signaling in plants. The level of promoter activity observed in the sdhaf2 background was between that of dsr1 and wild type (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1, top) demonstrating that the impairment in sdhaf2 was not completely disabled like it was in dsr1, which showed no induction in signal at any time point (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1, top). Addition of the SDH competitive inhibitor malonate confirmed that the SA-induced signal is SDH dependent and that it can be titrated, even in wild type (Fig. 1, B and C).

Despite general similarities between dsr1 and sdhaf2 in promoter activities, the GSTF8:luc signal could be partially rescued in sdhaf2 by the addition of excess succinate, suggesting some different properties of SDH in the two mutants. Kinetic analysis in dsr1 showed that the SDH enzyme has a significant difference in succinate affinity, catalytic efficiency, and inhibition by competitive inhibitors malonate/OAA compared to the wild type (Fig. 2, B and C). This made sense, as dsr1 has a point mutation located at the succinate binding site, which leads to an amino acid change from Ala to Thr (A581T; Gleason et al., 2011). This change appeared to cause a lower affinity for succinate and therefore a lower catalytic efficiency in dsr1 (Fig. 2, D and E). Alteration in SDH enzyme kinetics has also been shown in human SDH1 mutations. A point mutation A409C in the succinate binding site of SDH1 led to a 50% reduction of SDH activity and caused optic atrophy and myopathy (Birch-Machin et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2005). Mutation of R554Y in SDH1 caused an unstable SDH1 helix domain and also a 50% decrease in SDH activity and loss of ATP activation resulting in the neurodegenerative disorder Leigh-like syndrome (Bourgeron et al., 1995; Sun et al., 2005). To our knowledge, dsr1 is the first SDH1 mutation shown to alter the Km of the enzyme for succinate.

These data infer that a certain threshold of SDH activity is required to induce the GSTF8 SA-dependent promoter stress signal. This activity threshold cannot be reached in dsr1, and even with higher amounts of succinate no signal induction and no GSTF8 promoter response occurred (Fig. 4, bottom), leading to pathogen susceptibility (Gleason et al., 2011). This shows that a relatively subtle change in the Km of a metabolic enzyme can produce a binary switch in stress signaling, raising the possibility that natural variation in metabolic kinetics could be acted upon to improve plant stress sensitivity and tolerance to pathogens. In addition, endogenous inhibitors of SDH like oxaloacetate and malonate act as competitive inhibitors and therefore will change the apparent Km for succinate, thus acting dynamically in a manner not unlike the dsr1 mutation, as illustrated by the effect of malonate on wild-type signaling (Fig. 1, B and C).

Low Concentrations of SA Increase SQR Activity

SA is an effective signaling molecule, and only micromolar concentrations are required for these effects inside plant cells (Raskin et al., 1987; Wu et al., 2012). The basal level of SA can vary between species and even within the same plant family (Raskin et al., 1990). For Arabidopsis, basal levels of SA between 2 µmol and 8 µmol g−1 FW have been reported (Brodersen et al., 2005; Klessig et al., 2016; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999; Wildermuth et al., 2001), with SA rising to ∼40 µmol g−1 FW during infection, which has been equated to ∼70 µm inside infected plant cells (Bi et al., 1995). The importance of SA in response to biotic and abiotic stress and its involvement in the transcriptional regulation of defense genes has been extensively studied and reviewed (Herrera-Vásquez et al., 2015). Previous studies of the effect of SA on respiration have focused on the notion of this hormone as an inhibitor and uncoupler of the respiratory chain at concentrations >100 µm (Norman et al., 2004), but no systemic investigations of the effect of low µm levels on respiratory functions have been undertaken. We show here that SA influences the function of complex II at concentrations as low as 10 µm SA when applied to isolated mitochondria (Fig. 5B), potentially placing the effects in the physiological range for Arabidopsis and other SA binding proteins in plants with NPR4 and NRP3 having an SA affinity in nanomolar and micromolar range (Fu et al., 2012; Moreau et al., 2012) as well as several potential effector proteins (catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, carbonic anhydrase) that bind SA with an affinity of 3.7 to 14 µm (Chen et al., 1993a, 1993b; Durner and Klessig, 1995; Slaymaker et al., 2002).

SA Likely Interacts with the UQ Binding Site of Complex II

We show the effect of SA on SDH activity did not occur when electrons were accepted directly from SDH1, but only when they were accepted via a quinone. A chemical reaction between SA and the acceptor DCPIP can be excluded, as only very low activity was measured when no Q1 was present in the sample (Fig. 5B), showing that SA together with Q1 is necessary to allow the induction in activity. This implies that SA does not act via the succinate binding site of SDH1 but instead via or near the UQ binding site of SDH (Fig. 5, A and B). We also show that known UQ binding site inhibitors (TTFA, carboxin) can lead to an increase in SQR activity at low micromolar concentrations (Supplemental Fig. S5). TTFA and carboxin are generally described as complex II inhibitors in mammalian and plant systems, causing decreased SQR activity and mitochondrial respiration rates at high micromolar to millimolar concentrations (Byun et al., 2008; Jardim-Messeder et al., 2015; León et al., 2007; Miyadera et al., 2003; Ramsay et al., 1981). As noted previously, sensitivity of SQR to these inhibitors varies between different species; mammals show a very high sensitivity with IC50 values in micromolar concentrations (Miyadera et al., 2003), whereas Arabidopsis SQR is less sensitive, showing inhibitory effects at millimolar concentrations (Supplemental Fig. S5; León et al. (2007); Jardim-Messeder et al. (2015). It has also been shown that TTFA binds to a site within SDH3/4 based on x-ray crystallography (Sun et al., 2005). Two binding sites in SDH for quinones have been described for mammals and Escherichia coli (Sun et al., 2005; Yankovskaya et al., 2003): one site (Qp), located on the matrix side, and a second (Qd) near the intermembrane space site (Hägerhäll, 1997). UQ reduction is a single electron two-step transfer, forming an ubisemiquinone after the transfer of the first electron, before the complete reduction to ubiquinol occurs following the acceptance of the second electron (Hägerhäll, 1997). Inhibitors like TTFA are proposed to block the electron transfer between these two sites, causing electron leakage (Yankovskaya et al., 2003). SA may act similarly to these inhibitors and prevent complete reduction of UQ by blocking the electron transfer from Qp to Qd, which could cause electron leakage. Structural similarity between UQ, TTFA, and carboxin is not high in strictly chemical terms, but it would appear that SA could structurally mimic some features of both UQ and/or these inhibitors (Supplemental Fig. S8). If SA binds to membrane-embedded SDH3/4 at the UQ binding site as proposed, then this may explain why SDH subunits have not been identified in affinity assay screens for SA binding in Arabidopsis that focused on soluble proteins (Manohar et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2012). Neither the point mutation in dsr1 nor the assembly defect in sdhaf2 should affect the UQ site directly, and we did not observe a difference in the SA effect on SQR activity in either line. Although both mutant lines show SA induction, their overall SA-induced SQR activity level was still significantly lower than wild type and this threshold could be the basis of these mutant effects.

Previous studies have reported complex III as a potential SA binding enzyme (Nie et al., 2015). Within this study, we could not observe any SA effect on complex III activity in any of the lines; neither was there a genotypic difference among the SA treatments (Supplemental Fig. S4). Our results also showed that only when using succinate as substrate, and not when using NADH or malate + Glu, could SA drive H2O2 production above background levels in the absence of respiratory substrates. This strengthens our hypothesis that complex II has a SA binding site near the UQ site and is the major source of H2O2 in Arabidopsis mitochondria.

SA Stimulates SDH-Dependent H2O2 Production

The effect of SA stimulation of SDH activity in a manner associated with the UQ binding site could lead to reactions with oxygen to form ROS including superoxide (O2−). Within mitochondria, superoxide is rapidly dismutated by MnSOD to form H2O2. Our previous study showed a clear correlation between SA treatment and accumulation of H2O2 (Gleason et al., 2011). Wild-type seedlings treated with SA and the H2O2 scavenger catalase showed a reduced GSTF8 signal, showing that this signaling pathway is H2O2 dependent (Gleason et al., 2011). We also showed that exogenous H2O2 induces GSTF8 response in wild type as well as in sdhaf2 and dsr1, indicating that SDH is involved upstream of ROS signaling (Supplemental Fig. S1, bottom). We measured ROS in isolated mitochondria in the presence and absence of SA, together with succinate and ATP, using DCFDA as a fluorescent marker of H2O2 (Fig. 6). DCFDA reacts with any ROS, but as O2− is highly reactive, unstable, and nonmembrane permeable, H2O2 is the ROS that dominates DCFDA fluorescence in isolated mitochondria (Bienert and Chaumont, 2014; Huang et al., 2016). Both mutant lines show a lower basal H2O2 production rate compared to wild type. Micromolar concentrations of SA induced H2O2 production in all genotypes, but significantly less in the mutant lines compared to wild type (Fig. 6) and not significantly higher compared to AA treatment. Lower H2O2 production in both lines can be explained by their decreased SDH activity (Fig. 2B), even when stimulated by SA at the UQ site (Fig. 5B). Due to the lower rate of succinate oxidation in dsr1 and sdhaf2, fewer electrons are transferred to the UQ pool, decreasing its redox poise and slowing the rate of side reactions that would lead to superoxide and then H2O2 production. It appears that a threshold of SDH activity needs to be reached for increased H2O2 production to occur. This observation of enzymatic dependency is similar to the threshold we observed in the GSTF8:luc induction by SA (Figs. 1 and 4; Supplemental Fig. S1). Considering that sdhaf2 compared to dsr1 showed a higher GSTF8 promoter signal in the presence of exogenous succinate addition, one might expect to measure a higher H2O2 production in this line as well, but this could not be observed (Fig. 6). Differences in the mutants downstream of the SA stress signal pathway might occur to explain these observations.

We noted earlier that we observed a significant background signal with DCFDA that is caused by reactions independent of the respiratory substrate (Supplemental Fig. S7). We found it essential to run control samples parallel to the actual samples to exclude background signals (Fig. 6) that might be caused by site reactions in the sample itself or the autofluorescence of other sample components. Previous studies investigated the effect of SA in mitochondrial ROS production in Arabidopsis and reported a significant ROS induction after SA addition (Jardim-Messeder et al., 2015). However, no negative controls were used to exclude substrate-independent signals, which could mean that the actual substrate-dependent signal was significantly lower. In another study, H2O2 production in isolated mitochondria has been measured in the presence of different SA concentrations and different substrates for complex I and complex II (Nie et al., 2015). A very high induction of H2O2 production was shown after SA was added, but this study also lacks a negative control without substrate. Therefore, the scale of the measured signals in these reports might need reconsideration, as they could be substrate independent and might be mainly caused by background signals occurring in both assays.

We did not observe any significant ROS production above background signals when NADH or malate together with Glu was used as substrate (Supplemental Fig. S6B), showing that firstly, negative controls without any substrate are essential to determine that any significant signal is not independent of mitochondrial respiration and secondly, that succinate together with SA drives enhanced H2O2 production. This demonstrates that complex II can act as a major source of ROS production with higher rates than complex I,III or alternative NADH dehydrogenases, a phenomenon that has previously be shown in mammalian mitochondria where SDH was found to produce the highest amounts of ROS (Dedkova et al., 2013; Quinlan et al., 2012; Ralph et al., 2011) and recently in barley (Hordeum vulgare) roots, where complex II-derived ROS was shown to be the major source of mitochondrial ROS during mercury toxicity (Tamás and Zelinová, 2017).

The interplay between SA and H2O2 and which of these molecules acts first in plant defense appear to vary depending on the pathway being examined (Vlot et al., 2009). We have previously shown that GSTF8 regulation is H2O2 dependent (Gleason et al., 2011; Supplemental Fig. S1, bottom) and that accumulation of H2O2 follows the SA effect and quantitatively depends on the degree of function of the mitochondrial SDH complex. Earlier studies also showed that SA can enhance H2O2 production (Shirasu et al., 1997). Recent studies identified GSTF8 as a SA binding protein (Manohar et al., 2015; Tian et al., 2012), but the biological consequences of that interaction and whether it is involved in stress signaling remain unclear. Based on our data, it does not seem to interact with GSTF8:luc signaling, as dsr1 does not show a signal response after SA treatment (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1, top).

Besides mitochondria, ROS are also produced in the apoplast, chloroplasts, and peroxisomes (Herrera-Vásquez et al., 2015; Love et al., 2008; Vlot et al., 2009) under different stress conditions, and the interaction between organelles is important for an efficient stress response (Herrera-Vásquez et al., 2015). Microarray analysis showed that 18 genes were differentially expressed after SA treatment in dsr1 vs wild type (Gleason et al., 2011), showing that SA induces only a selection of plant defense genes via this pathway and, notably, it does not directly affect the expression of classical NPR1 targets (Gleason et al., 2011). The SDH-dependent SA pathway described here is thus one part of SA signaling in plants that likely operates independently of how SA is perceived via NPR1/3/4 in plants and in parallel to other ROS-linked pathways that depend on SA-binding proteins (Moreau et al., 2012). Finally, our results add to a growing body of work showing the importance of mitochondria in plant stress/defense responses (Huang et al., 2016), at least in part through the increased production of H2O2 from mitochondrial respiratory complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of Arabidopsis Hydroponic Plants

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Col-0) transgenic lines (JC66, called wild type throughout the manuscript), dsr1, and sdhaf2 mutant seeds were washed in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 2 min and in sterilization solution (5% [v/v] bleach, 0.1% [v/v] Tween 20) for 5 min with periodical shaking. Seeds were washed fice times in sterile water before being dispensed into 250-mL plastic vessels containing 80 mL of half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media (without vitamins, half-strength Gamborg B5 vitamin solution, 5 mm MES, and 2.5% [w/v] Suc, pH 7). Hydroponic cultures were grown under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark period with light intensity of 100 to 125 µmol m2 s−1 at 22°C for 2 weeks or continuously in the dark for the DCFDA measurements.

GSTF8:luc Signaling of Arabidopsis Seedlings

Four-day-old seedlings of the wild type, dsr1, and sdhaf2 (in the JC66 background) were grown on MS media plus luciferin (0.5× MS medium without vitamins, 1% [w/v] Suc, pH 7.0, and 50 µm luciferin [Biosynth]) with or without malonate or succinate using 92 × 16-mm petri dishes as described previously (Gleason et al., 2011). After incubation with 7 mm SA for 40 min, whole plant bioluminescence was captured over 24 h using a NightShade imager (Berthold Technologies with data calculated in average light units (counts/s) per seedling using IndiGo (v 2.0.3.0) software (Berthold Technologies).

Isolation of Mitochondria from Hydroponic Cultures

Mitochondria were isolated from 2-week-old hydroponically grown Arabidopsis plants using a previously described method from Millar et al. (2001), with slight modifications. Plant material was homogenized in grinding buffer (0.3 m Suc, 25 mm tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 1% [w/v] PVP-40, 2 mm EDTA, 10 mm KH2PO4, 1% [w/v] BSA, and 20 mm ascorbic acid, pH 7.5) using mortar and pestle for 2 to 5 min, twice. The homogenate was filtered through four layers of Miracloth and centrifuged at 2,500g for 5 min; the resulting supernatant was then centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in Suc wash medium (0.3 m Suc, 0.1% [w/v] BSA, and 10 mm TES, pH 7.5) and carefully layered over 35 mL PVP-40 gradient (30% Percoll and 0–4% PVP). The gradient was centrifuged at 40,000g for 40 min. The mitochondrial band was collected and washed three times in Suc wash buffer without BSA at 20,000g for 20 min.

Measurement of SDH Activity and Kinetic Calculations

SDH activity was measured directly at the subunit SDH1-1 by succinate-dependent DCPIP reduction at 600 nm. Isolated Arabidopsis mitochondria (50 µg) were used in 1 mL of reaction medium (50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.1% [w/v] BSA, 10 mm potassium cyanide, 0.12 mm DCPIP, and 1.6 mm PMS). To calculate SDH activity, an extinction coefficient of 21 mm−1 cm−1 at 600 nm for DCPIP was used. Brooks Kinetic Software and linear Hanes-Plot calculations were used for kinetic calculations. For measurements targeting the UQ binding site of SDH (SQR activity), 80 µm Coenzyme Q1 instead of PMS was used in the reaction medium (Miyadera et al., 2003).

Measurement of Complex III Activity

The assay was performed as previously described in Petrosillo et al. (2003). Isolated mitochondria (50 µg) were used in a 1-mL reaction mixture containing 3 mm sodium azide, 1.5 µm rotenone, 50 µm cyt c, and 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. The reaction was started by the addition of 50 µm ubiquinol Q10. Complex III activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 550 nm following the reduction of cyt c, and a rate in nmol cyt c/min/mg Mit. was calculated using extinction coefficient (EmM) of 28.0 (reduced cyt c).

Measurement of Oxygen Consumption Using an O2 Clark Electrode

Oxygen consumption was measured using an O2 Clark electrode. Isolated Arabidopsis mitochondria (100 µg) were used and oxygen uptake measured as previously described in Huang et al. (2013) in the presence of 5 mm succinate, 1 mm NADH, or 10 mm malate + Glu. To investigate the effect of SA on respiration, concentrations from 0.01 to 1 mm were added after the substrate.

Mitochondrial ROS Measurements Using DCFDA

DCFDA, a cell permeant reagent that is reacting with ROS within the cell, was used. DCFDA is deacetylated by cellular esterases and forms the fluorescent compound 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein once it is oxidized by ROS. 2′, 7′-Dichlorofluorescein can be detected by fluorescence spectroscopy using excitation/emission spectra of 480/520 nm. Freshly isolated mitochondria (10 µg) from hydroponically grown Arabidopsis plants (continuously in the dark) were transferred in 50 µL buffer (0.3 m Suc, 5 mm KH2PO4, 10 mm TES, 10 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgSO4, and 0.1% [w/v] BSA, pH 7.2). DCFDA was diluted to 10 µm, a final volume of 50 µL in the same buffer solution together with the individual substrates. Both solutions were transferred and mixed in a 96-well plate to a final volume of 100 µL. Fluorescence was measured over 10 min and the slope was calculated.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. GSTF8:luc induction in the presence of 1 mm SA or H2O2.

Supplemental Figure S2. Inhibition of competitive inhibitor malonate in the presence of 5 mm succinate.

Supplemental Figure S3. Significant differences in SQR activity and oxygen consumption between genotypes and SA treatment.

Supplemental Figure S4. Complex III activity in the presence of SA.

Supplemental Figure S5. TTFA (A) and carboxin (B) increase SQR activity.

Supplemental Figure S6. Complex I and alternative NADH dehydrogenase-dependent ROS and oxygen uptake measurements in the presence of SA.

Supplemental Figure S7. Measured background signals for mitochondrial H2O2 productionin the absence of substrates and effectors.

Supplemental Figure S8. Comparison of structures for TTFA, carboxin, SA, and UQ-1.

Supplemental Table S1. P values of statistical analysis between genotypes and treatment (Fisher lsd test).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Prof. William Plaxton (Queen's University, Canada) for advice on kinetic analysis.

Glossary

- AA

antimycin A

- DCFDA

2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- DCPIP

dichlorophenolindophenol

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- mtROS

reactive oxygen species inside mitochondria

- OAA

oxaloacetic acid

- PMS

phenazine methosulfate

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

salicylic acid

- SQR

succinate:quinone reductase

- TTFA

thenoyltrifluoroacetone

- UQ

ubiquinone

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP130102918), the facilities of the ARC Centre of Excellence Program (CE140100008), and by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). S.H. and A.H.M. were funded as ARC Australian Future Fellows (FT130101338 and FT110100242, respectively). Work by O.V.A. and K.B.S. on this project was also supported by ARC Discovery Project DP160103573. K.B. holds a Scholarship for International Research Fees and University International Stipend from the University of Western Australia.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, Starkov AA (2005) Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Mosc) 70: 200–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attaran E, Zeier TE, Griebel T, Zeier J (2009) Methyl salicylate production and jasmonate signaling are not essential for systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 954–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi YM, Kenton P, Mur L, Darby R, Draper J (1995) Hydrogen peroxide does not function downstream of salicylic acid in the induction of PR protein expression. Plant J 8: 235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert GP, Chaumont F (2014) Aquaporin-facilitated transmembrane diffusion of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840: 1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert GP, Møller AL, Kristiansen KA, Schulz A, Møller IM, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP (2007) Specific aquaporins facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen peroxide across membranes. J Biol Chem 282: 1183–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch-Machin MA, Taylor RW, Cochran B, Ackrell BA, Turnbull DM (2000) Late-onset optic atrophy, ataxia, and myopathy associated with a mutation of a complex II gene. Ann Neurol 48: 330–335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T, Rustin P, Chretien D, Birch-Machin M, Bourgeois M, Viegas-Péquignot E, Munnich A, Rötig A (1995) Mutation of a nuclear succinate dehydrogenase gene results in mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiency. Nat Genet 11: 144–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Malinovsky FG, Hématy K, Newman MA, Mundy J (2005) The role of salicylic acid in the induction of cell death in Arabidopsis acd11. Plant Physiol 138: 1037–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SP. (1992) A simple computer program with statistical tests for the analysis of enzyme kinetics. Biotechniques 13: 906–911 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun HO, Kim HY, Lim JJ, Seo YH, Yoon G (2008) Mitochondrial dysfunction by complex II inhibition delays overall cell cycle progression via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biochem 104: 1747–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Chao G, Singh KB (1996) The promoter of a H2O2-inducible, Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase gene contains closely linked OBF- and OBP1-binding sites. Plant J 10: 955–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Ricigliano JW, Klessig DF (1993a) Purification and characterization of a soluble salicylic acid-binding protein from tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 9533–9537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Silva H, Klessig DF (1993b) Active oxygen species in the induction of plant systemic acquired resistance by salicylic acid. Science 262: 1883–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouchani ET, Pell VR, Gaude E, Aksentijević D, Sundier SY, Robb EL, Logan A, Nadtochiy SM, Ord EN, Smith AC, et al. (2014) Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 515: 431–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedkova EN, Seidlmayer LK, Blatter LA (2013) Mitochondria-mediated cardioprotection by trimetazidine in rabbit heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 59: 41–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dröse S, Brandt U (2008) The mechanism of mitochondrial superoxide production by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem 283: 21649–21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durner J, Klessig DF (1995) Inhibition of ascorbate peroxidase by salicylic acid and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, two inducers of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 11312–11316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouhar F, Yang Y, Kumar D, Chen Y, Fridman E, Park SW, Chiang Y, Acton TB, Montelione GT, Pichersky E, et al. (2005) Structural and biochemical studies identify tobacco SABP2 as a methyl salicylate esterase and implicate it in plant innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1773–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu ZQ, Yan S, Saleh A, Wang W, Ruble J, Oka N, Mohan R, Spoel SH, Tada Y, Zheng N, Dong X (2012) NPR3 and NPR4 are receptors for the immune signal salicylic acid in plants. Nature 486: 228–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi D, Goffrini P, Uziel G, Horvath R, Klopstock T, Lochmüller H, D’Adamo P, Gasparini P, Strom TM, Prokisch H, et al. (2009) SDHAF1, encoding a LYR complex-II specific assembly factor, is mutated in SDH-defective infantile leukoencephalopathy. Nat Genet 41: 654–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason C, Huang S, Thatcher LF, Foley RC, Anderson CR, Carroll AJ, Millar AH, Singh KB (2011) Mitochondrial complex II has a key role in mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species influence on plant stress gene regulation and defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10768–10773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hägerhäll C. (1997) Succinate: quinone oxidoreductases. Variations on a conserved theme. Biochim Biophys Acta 1320: 107–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H-X, Khalimonchuk O, Schraders M, Dephoure N, Bayley J-P, Kunst H, Devilee P, Cremers CWRJ, Schiffman JD, Bentz BG, et al. (2009) SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science 325: 1139–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzler T, Steudle E (2000) Transport and metabolic degradation of hydrogen peroxide in Chara corallina: model calculations and measurements with the pressure probe suggest transport of H(2)O(2) across water channels. J Exp Bot 51: 2053–2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Vásquez A, Salinas P, Holuigue L (2015) Salicylic acid and reactive oxygen species interplay in the transcriptional control of defense genes expression. Front Plant Sci 6: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Millar AH (2013) Succinate dehydrogenase: the complex roles of a simple enzyme. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Taylor NL, Ströher E, Fenske R, Millar AH (2013) Succinate dehydrogenase assembly factor 2 is needed for assembly and activity of mitochondrial complex II and for normal root elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant J 73: 429–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Van Aken O, Schwarzländer M, Belt K, Millar AH (2016) The roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cellular signaling and stress response in plants. Plant Physiol 171: 1551–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardim-Messeder D, Caverzan A, Rauber R, de Souza Ferreira E, Margis-Pinheiro M, Galina A (2015) Succinate dehydrogenase (mitochondrial complex II) is a source of reactive oxygen species in plants and regulates development and stress responses. New Phytol 208: 776–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klessig DF, Tian M, Choi HW (2016) Multiple targets of salicylic acid and its derivatives in plants and animals. Front Immunol 7: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudin AP, Bimpong-Buta NY, Vielhaber S, Elger CE, Kunz WS (2004) Characterization of superoxide-producing sites in isolated brain mitochondria. J Biol Chem 279: 4127–4135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire BD, Oyedotun KS (2002) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1553: 102–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León G, Holuigue L, Jordana X (2007) Mitochondrial complex II Is essential for gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 1534–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CA, Romani RJ (1988) Inhibition of ethylene biosynthesis by salicylic Acid. Plant Physiol 88: 833–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love AJ, Milner JJ, Sadanandom A (2008) Timing is everything: regulatory overlap in plant cell death. Trends Plant Sci 13: 589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar M, Tian M, Moreau M, Park SW, Choi HW, Fei Z, Friso G, Asif M, Manosalva P, von Dahl CC, et al. (2015) Identification of multiple salicylic acid-binding proteins using two high throughput screens. Front Plant Sci 5: 777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar AH, Liddell A, Leaver CJ (2001) Isolation and subfractionation of mitochondria from plants. Methods Cell Biol 65: 53–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadera H, Shiomi K, Ui H, Yamaguchi Y, Masuma R, Tomoda H, Miyoshi H, Osanai A, Kita K, Ōmura S (2003) Atpenins, potent and specific inhibitors of mitochondrial complex II (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 473–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons A. (2005) Regulatory and functional interactions of plant growth regulators and plant glutathione S-transferases (GSTs). Vitam Horm 72: 155–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau M, Tian M, Klessig DF (2012) Salicylic acid binds NPR3 and NPR4 to regulate NPR1-dependent defense responses. Cell Res 22: 1631–1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C, Métraux JP (1999) Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 11: 1393–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie S, Yue H, Zhou J, Xing D (2015) Mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species play a vital role in the salicylic acid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 10: e0119853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman C, Howell KA, Millar AH, Whelan JM, Day DA (2004) Salicylic acid is an uncoupler and inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transport. Plant Physiol 134: 492–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuma E, Nozawa R, Murata Y, Miura K (2014) Accumulation of endogenous salicylic acid confers drought tolerance to Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav 9: e28085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosillo G, Ruggiero FM, Di Venosa N, Paradies G (2003) Decreased complex III activity in mitochondria isolated from rat heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion: role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. FASEB J 17: 714–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Perevoshchikova IV, Treberg JR, Ackrell BA, Brand MD (2012) Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J Biol Chem 287: 27255–27264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph SJ, Moreno-Sánchez R, Neuzil J, Rodríguez-Enríquez S (2011) Inhibitors of succinate: quinone reductase/Complex II regulate production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and protect normal cells from ischemic damage but induce specific cancer cell death. Pharm Res 28: 2695–2730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay RR, Ackrell BA, Coles CJ, Singer TP, White GA, Thorn GD (1981) Reaction site of carboxanilides and of thenoyltrifluoroacetone in complex II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78: 825–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MV, Davis KR (1999) Ozone-induced cell death occurs via two distinct mechanisms in Arabidopsis: the role of salicylic acid. Plant J 17: 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I, Ehmann A, Melander WR, Meeuse BJ (1987) Salicylic acid: a natural inducer of heat production in arum lilies. Science 237: 1601–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I, Skubatz H, Tang W, Meeuse BJD (1990) Salicylic acid levels in thermogenic and non-thermogenic plants. Ann Bot (Lond) 66: 369–373 [Google Scholar]

- Sappl PG, Carroll AJ, Clifton R, Lister R, Whelan J, Harvey Millar A, Singh KB (2009) The Arabidopsis glutathione transferase gene family displays complex stress regulation and co-silencing multiple genes results in altered metabolic sensitivity to oxidative stress. Plant J 58: 53–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaratna T, Touchell D, Bunn E, Dixon K (2000) Acetyl salicylic acid (Aspirin) and salicylic acid induce multiple stress tolerance in bean and tomato plants. Plant Growth Regul 30: 157–161 [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu K, Nakajima H, Rajasekhar VK, Dixon RA, Lamb C (1997) Salicylic acid potentiates an agonist-dependent gain control that amplifies pathogen signals in the activation of defense mechanisms. Plant Cell 9: 261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker DH, Navarre DA, Clark D, del Pozo O, Martin GB, Klessig DF (2002) The tobacco salicylic acid-binding protein 3 (SABP3) is the chloroplast carbonic anhydrase, which exhibits antioxidant activity and plays a role in the hypersensitive defense response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11640–11645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Huo X, Zhai Y, Wang A, Xu J, Su D, Bartlam M, Rao Z (2005) Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II. Cell 121: 1043–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamás L, Zelinová V (2017) Mitochondrial complex II-derived superoxide is the primary source of mercury toxicity in barley root tip. J Plant Physiol 209: 68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, von Dahl CC, Liu PP, Friso G, van Wijk KJ, Klessig DF (2012) The combined use of photoaffinity labeling and surface plasmon resonance-based technology identifies multiple salicylic acid-binding proteins. Plant J 72: 1027–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlot AC, Dempsey DA, Klessig DF (2009) Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu Rev Phytopathol 47: 177–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth MC, Dewdney J, Wu G, Ausubel FM (2001) Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 414: 562–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhang D, Chu JY, Boyle P, Wang Y, Brindle ID, De Luca V, Després C (2012) The Arabidopsis NPR1 protein is a receptor for the plant defense hormone salicylic acid. Cell Reports 1: 639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalpani N, Silverman P, Wilson TM, Kleier DA, Raskin I (1991) Salicylic acid is a systemic signal and an inducer of pathogenesis-related proteins in virus-infected tobacco. Plant Cell 3: 809–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Törnroth S, Luna-Chavez C, Miyoshi H, Léger C, Byrne B, Cecchini G, Iwata S (2003) Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 299: 700–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.