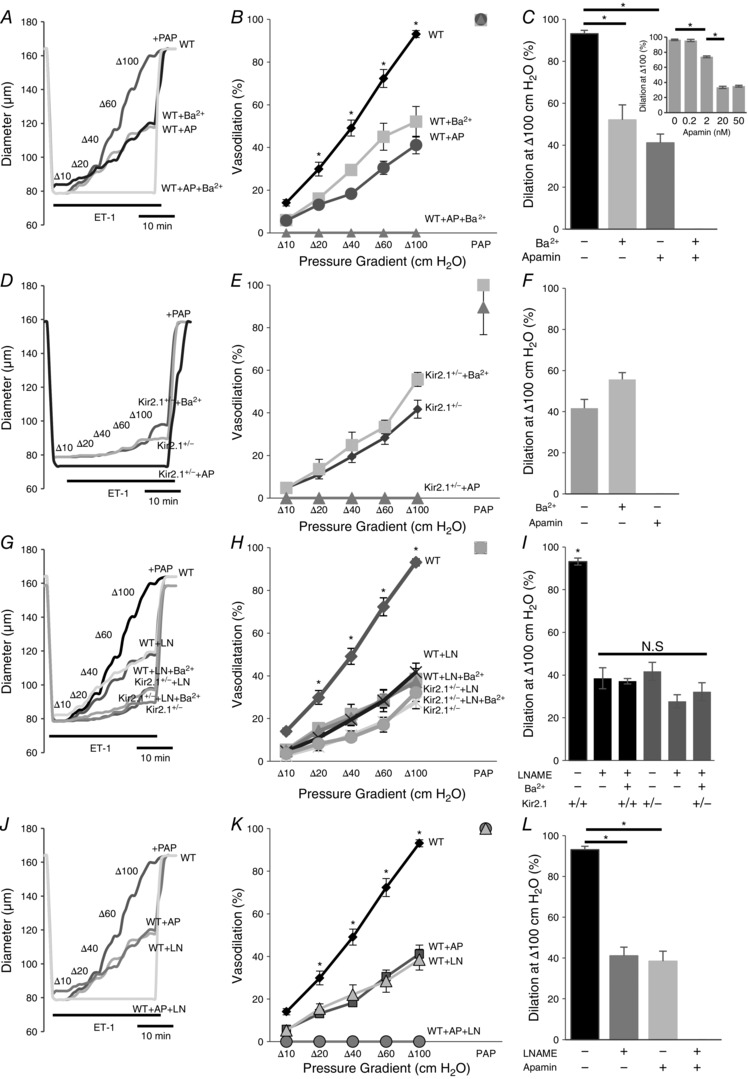

Figure 9. Kir2.1 and SK regulate flow‐induced vasodilatation by NO‐dependent and NO‐independent pathways.

A, representative FIV trace of pre‐constricted (ET‐1) mesenteric arteries harvested from WT mice with and without 20 nm apamin (AP), 300 μm Ba2+, or both. B, average flow‐induced dilatations of arteries harvested from WT mice with the same experimental conditions described in A (n = 4 arteries per condition, * P < 0.05). D, representative FIV trace of mesenteric arteries harvested from Kir2.1+/− mice exposed to the same experimental conditions described in A. E, average flow‐induced dilatations arteries harvested from Kir2.1+/− mice exposed to the same experimental conditions described in A (n = 4 arteries per condition, * P < 0.05). G, representative FIV trace of arteries harvested from WT or Kir2.1+/− mice with and without 100 μm l‐NAME (LN). H, average flow‐induced dilatations of arteries from WT or Kir2.1+/− mice with the same experimental conditions described in G (n = 4 arteries per condition). J, representative FIV trace of arteries harvested from WT mice with and without 20 nm apamin, 100 μm l‐NAME, or both. K, average flow‐induced dilatations of mesenteric arteries harvested from WT mice with the same experimental conditions described in G (n = 5 arteries per condition, * P < 0.05). C, F, I and L: average dilatations at Δ100 cmH2O for the same experimental conditions as described in B, E, H and K, respectively. C, inset: dose–response curve for apamin of FIV in WT mesenteric arteries at average dilatations at Δ100 cmH2O (n = 4, * P < 0.05). Apamin was perfused extravascularly. ET‐1, endothelin‐1; PAP, papaverine (added at Δ100 cmH2O to test the vessels’ maximal dilatation).