Abstract

Severe stomatitis may lead to the need to interrupt or discontinue cancer therapy and, thus, may affect control of the primary disease. Stomatitis may also increase the risk of local and systemic infection and significantly affects the quality of life and the cost of care. The present study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of two traditional herbal medicines in controlling treatment-induced stomatitis in a small cohort of lung cancer patients treated with afatinib. All patients who were treated with afatinib for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutated nonsmallcell lung cancer (NSCLC) between January, 2015 and March, 2016, were included in this study. During the study period, a total of 14 NSCLC patients were treated with afatinib, an EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). Two patients already had stomatitis at the time of initiation of afatinib therapy; among the remaining 12 NSCLC patients, 2 (16.7%) developed stomatitis. All the lesions in the 4 patients who developed stomatitis were completely alleviated after 2 weeks of therapy with Aznol mouthwash, a chamomile extract with anti-inflammatory effects, and Hangeshashinto, a traditional herbal (Kampo) medicine. Afatinib therapy was re-initiated, but none of the patients developed stomatitis thereafter. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report evaluating oral care and management of stomatitis. This type of care and treatment may reduce the incidence of complications associated with EGFR-TKI therapy.

Keywords: stomatitis, afatinib, chamomile extract, Hangeshashinto, traditional herbal medicine, Kampo

Introduction

Mucosal complications, such as stomatitis, including aphtha and ulcerative lesions, are common with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (1). In the Lux-Lung-3 trial, 72.1% of the patients treated with afatinib developed stomatitis, with 8.7% exhibiting grade >3 stomatitis (2). Corticosteroids have been used to treat this complication; however, a standard management for TKI-induced stomatitis has not yet been established.

Azulene, a chamomile extract, possesses anti-inflammatory properties (3–6). Sodium azulene sulfonate (Azunol) is derived from azulene and is used to treat chronic gastritis and ulcers (7,8). The toxicological safety of Azunol preparations in the oral cavity has been previously described (9,10), and Azunol has been used for gargle and mouthwash preparations. To evaluate the management of stomatitis, oral care with a mouthwash and gargle liquid containing Azunol was administered to patients treated with afatinib, a second-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-TKI. With regard to Hangeshashinto, a traditional herbal (Kampo) medicine, there have been previous reports of its favorable effects on chemotherapy- and chemoradiotherapy-induced stomatitis (11–14). Patients who developed stomatitis were treated with a mouthwash containing Hangeshashinto, which has been found to reduce CPT-11induced gastrointestinal tract complications (15,16). The present study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of these medicines in controlling stomatitis in a small cohort of lung cancer patients treated with afatinib.

Patients and methods

Patients

This singlecenter, retrospective chart review study was conducted at the Ryugasaki Saiseikai Hospital (Ryugasaki, Japan). All patients who were treated with afatinib for EGFRmutated nonsmallcell lung cancer (NSCLC) between January, 2015 and March, 2016 were included in this study. The study conformed to the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Studies issued by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Ryugasaki Saiseikai Hospital and Mito Medical Center, University of Tsukuba (no. 16–16). Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC), version 3.0.

Oral care protocol

The oral care protocol included assessment of the oral cavity by a doctor prior to TKI therapy, self-management or nurse assistance if necessary [brushing the teeth, gums and tongue using a soft toothbrush, and oral care plus 5 ml of Azunol gargle liquid 4% mouthwash (Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) taken four times daily]. The appearance of the gingiva and teeth was daily assessed by nurses. Treatment with Hangeshashinto was initiated when mild mucositis occurred (grade >1 according to the CTC criteria). The protocol was started immediately prior to TKI therapy and was included in the medical records. The evaluation of safety and efficacy was based on adverse events (AEs), physical examination and laboratory examinations.

Results

Patient characteristics

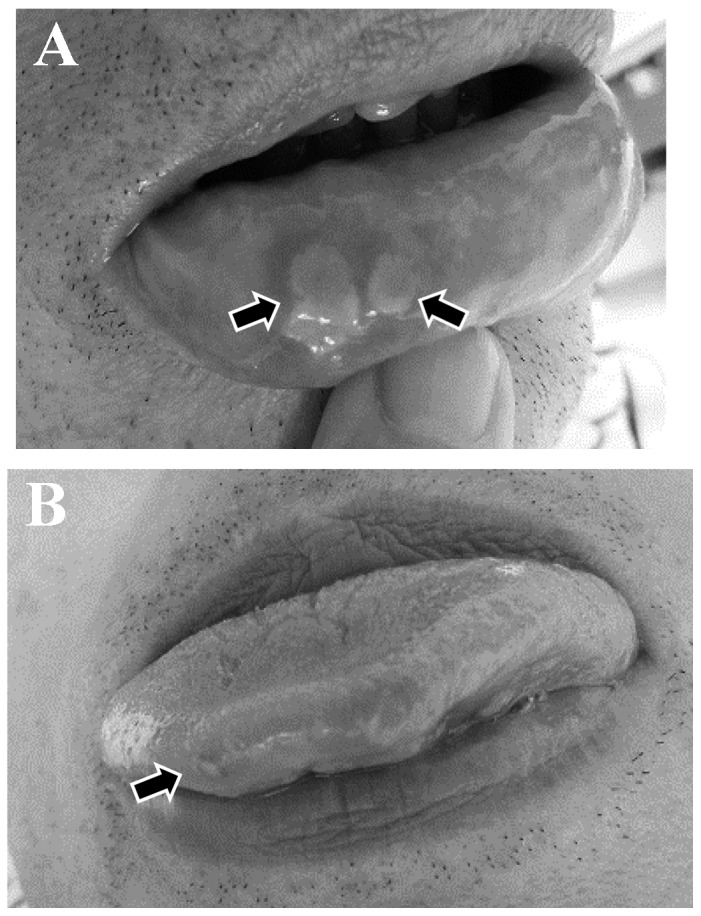

During the study period, 14 NSCLC patients were treated with afatinib. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table I. Two patients with stomatitis prior to the initiation of Aznol mouthwash and Hangeshashinto therapy are shown in Fig. 1. Of the 14 patients, 2 already had stomatitis (grade 1 and 2, respectively) at the time of initiation of afatinib therapy. These 2 patients were treated with Aznol mouthwash and Hangeshashinto. Of the remaining 12 NSCLC patients, 2 (1 man and 1 woman; 16.7%) developed grade 2 stomatitis and grade 2 dysgeusia (‘sweet taste failure’). All stomatitis patients developed the complication within 2 weeks from the initiation of afatinib therapy. Afatinib was discontinued for 1 week and the patients received Aznol mouthwash and a prescription of Hangeshashinto. All the lesions were completely alleviated 2 weeks after the initiation of Aznol and Hangeshashinto therapy. Afatinib therapy was re-initiated, but none of the patients developed stomatitis thereafter.

Table I.

Characteristics of 14 patients treated with afatinib.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 71 |

| Range | 55 84 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (50.0) |

| Female | 7 (50.0) |

| Performance status | |

| 0–1 | 10 (71.4) |

| 2–4 | 4 (28.6) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 14 (100.0) |

| EGFR mutations | |

| Ex21 L858R | 4 (28.6) |

| Ex19 del | 9 (63.3) |

| Ex18 G719X | 1 (7.1) |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Figure 1.

Two patients who had developed stomatitis of (A) the lip and (B) the tongue (arrows) prior to the initiation of Aznol mouthwash and Hangeshashinto therapy.

Discussion

Stomatitis is one of the most common AEs encountered in TKI therapy for NSCLC. Stomatitis may limit the patients' ability to tolerate chemotherapy and their nutritional status is compromised; it may also drastically affect cancer treatment and the patients' quality of life. The exact pathophysiology underlying the development of stomatitis has not been fully elucidated; however, it may be classified as direct and indirect stomatitis (17). TKIs may interfere with the normal turnover of the epithelial cells, leading to mucosal injury; it may also occur due to indirect invasion by microorganisms.

Afatinib is a second-line TKI, which covalently binds to a tyrosine kinase, preventing tumor growth by continuously inhibiting its phosphorylation; as a result, it exerts a strong antitumor effect in EGFRmutated NSCLC patients (2,18). However, afatinib is associated with certain AEs, such as skin rash, paronychia and stomatitis (2,18). The incidence of these AEs is not low, and these complications may occasionally require treatment discontinuation. In the Lux-Lung 3 trial, a 70% incidence of mucositis was reportedin patients treated with afatinib (2).

Oral care during treatment is crucial for preventing the development of stomatitis. Several treatment options are available for preventing and treating this condition, but none have yet been established as standard treatment. Efforts are currently focused on better understanding this condition, so that the optimal therapeutic regimens may be selected. Although stomatitis is rarely life-threatening, it interferes with cancer treatment to a great extent. Progress in the prevention and management of stomatitis will significantly improve the quality of life of the patients.

The mainstay of management of chemotherapy- or radiation-induced stomatitis is thorough oral hygiene and rinsing with certain remedies (19–21), although none have been established as standard treatment at present. There have been some reports of the favorable effects of Hangeshashinto on chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy-induced stomatitis (11–14). As regards EGFR-TKIinduced stomatitis, to the best of our knowledge, there have no reports evaluating oral care in the management of stomatitis to date. Although the number of patients included in this study was limited, the results indicating that the incidence of stomatitis was decreased by Aznol mouthwash and Hangeshashinto therapy are considered to be meaningful. Compared with skin rash and paronychia, stomatitis appears to be overlooked, as some patients have no such complaints. However, these lesions may be identified upon careful oral assessment by certified nurses. We herein demonstrated that Azunol mouthwash and Hangeshashinto effectively controlled EGFR-TKI-induced stomatitis, without any AEs. This preventive care and treatment may reduce the incidence of oral complications associated with EGFR-TKI therapy.

References

- 1.Califano R, Tariq N, Compton S, Fitzgerald DA, Harwood CA, Lal R, Lester J, McPhelim J, Mulatero C, Subramanian S, et al. Expert Consensus on the Management of Adverse Events from EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in the UK. Drugs. 2015;75:1335–1348. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O'Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, Geater SL, Orlov S, Tsai CM, Boyer M, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ge ZD, Auchampach JA, Piper GM, Gross GJ. Comparison of cardioprotective efficacy of two thromboxane A2 receptor antagonists. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:481–488. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200303000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rekka E, Chrysselis M, Siskou I, Kourounakis A. Synthesis of new azulene derivatives and study of their effect on lipid peroxidation and lipoxygenase activity. Chem Pharm Bull. 2002;50:904–907. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akagi M, Matsui N, Mochizuki S, Tasaka K. Inhibitory effect of egualen sodium: A new stable derivative of azulene on histamine release from mast cell-like cells in the stomach. Pharmacology. 2001;63:203–209. doi: 10.1159/000056135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kourounakis AP, Rekka EA, Kourounakis PN. Antioxidant activity of guaiazulene and protection against paracetamol hepatotoxicity in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:938–942. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yano S, Horie S, Wakabayashi S, Mochizuki S, Tomiyama A, Watanabe K. Increasing effect of sodium 3-ethyl-7-isopropyl-1-azulenesulfonate 1/3 hydrate (KT1-32), a novel antiulcer agent, on gastric mucosal blood flow in anesthetized. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1990;70:253–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okabe S, Takeuchi K, Mori Y, Furukawa O, Yamada Y. [Effects of KT1-32 on acute gastric lesions and duodenal ulcers induced in rats] Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1986;88:467–476. doi: 10.1254/fpj.88.467. (in Japanese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seki J, Mukai H, Sugiyama M. Studies on the absorption of sodium guaiazulene-3-sulfonate. II. Absorption mechanism from nasal and intestinal membrane. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1985;8:337–343. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.8.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanzlik RP, Bhatia P. Metabolism of azulene in rats. Xenobiotica. 1981;11:779–783. doi: 10.3109/00498258109045882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda C, Munemoto Y, Mishima H, Nagata N, Oshiro M, Kataoka M, Sakamoto J, Aoyama T, Morita S, Kono T. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II study of TJ-14 (Hangeshashinto) for infusional fluorinated-pyrimidine-based colorectal cancer chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2767-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashita T, Araki K, Tomifuji M, Kamide D, Tanaka Y, Shiotani A. A traditional Japanese medicine-Hangeshashinto (TJ-14)-alleviates chemoradiation-induced mucositis and improves rates of treatment completion. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2315-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoyama T, Nishikawa K, Takiguchi N, Tanabe K, Imano M, Fukushima R, Sakamoto J, Oba MS, Morita S, Kono T, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II study of TJ-14 (hangeshashinto) for gastric cancer chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:1047–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2440-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kono T, Kaneko A, Matsumoto C, Miyagi C, Ohbuchi K, Mizuhara Y, Miyano K, Uezono Y. Multitargeted effects of hangeshashinto for treatment of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis on inducible prostaglandin E2 production in human oral keratinocytes. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13:435–445. doi: 10.1177/1534735413520035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okumi H, Koyama A. Kampo medicine for palliative care in Japan. Biopsychosoc Med Jan. 2014;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohnishi S, Takeda H. Herbal medicines for the treatment of cancer chemotherapy-induced side effects. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00014. Front Pharmacol. 2015 Feb;10(6):14. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naidu MU, Ramana GV, Rani PU, Mohan IK, Suman A, Roy P. Chemotherapy-induced and/or radiation therapy-induced oral mucositis-complicating the treatment of cancer. Neoplasia. 2004;6:423–431. doi: 10.1593/neo.04169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ke EE, Wu YL. Afatinib in the first-line treatment of epidermal-growth-factor-receptor mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer: A review of the clinical evidence. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10:256–264. doi: 10.1177/1753465816634545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bardy J, Molassiotis A, Ryder WD, Mais K, Sykes A, Yap B, Lee L, Kaczmarski E, Slevin N. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial of active manuka honey and standard oral care for radiation-induced oral mucositis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogata J, Minami K, Horishita T, Shiraishi M, Okamoto T, Terada T, Sata T. Gargling with sodium azulene sulfonate reduces the postoperative sore throat after intubation of the trachea. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:290–293. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000156565.60082.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen SH, Wang LW, Lin YH, Jen YM, Chung YL. Phenylbutyrate mouthwash mitigates oral mucositis during radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in patients with head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]