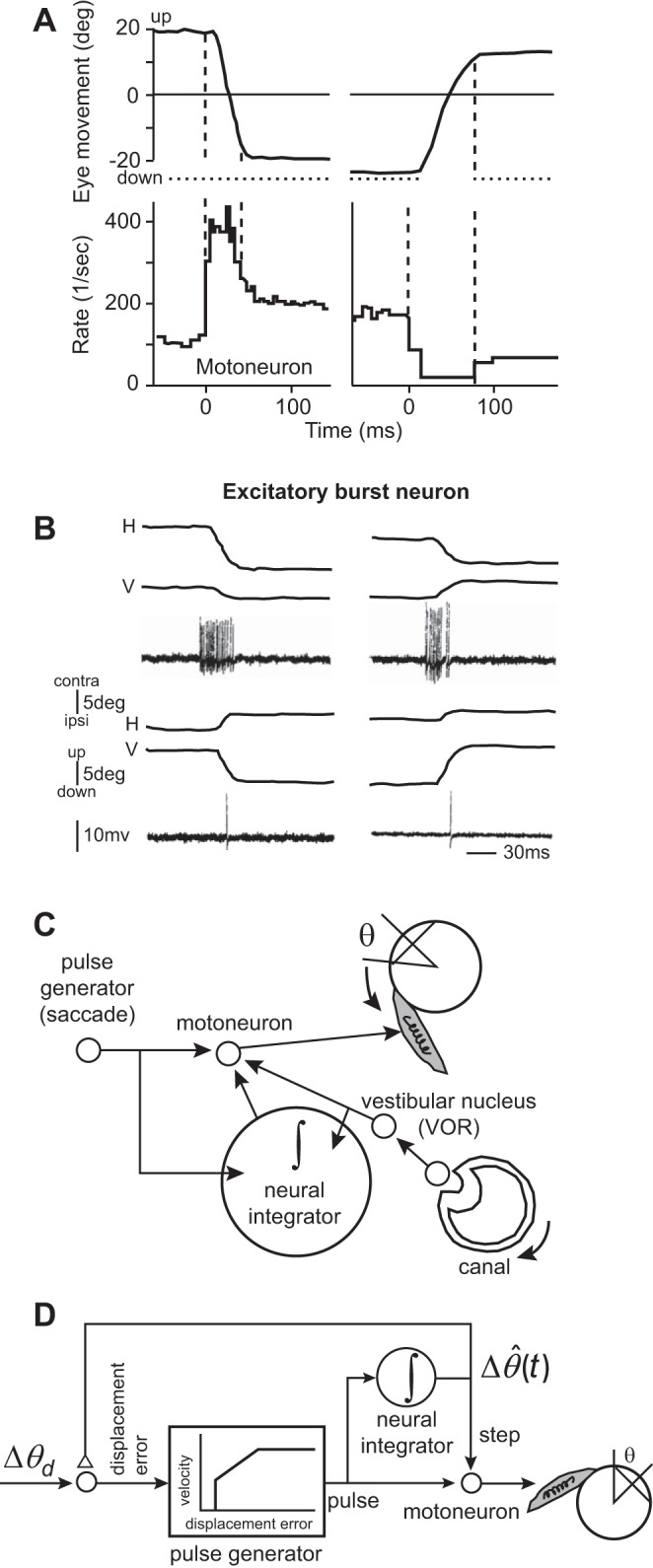

Fig. 1.

Activity of motoneurons that innervate the eye muscles includes information regarding moving the eyes, as well as holding the eyes. However, activity of some premotor neurons that project to these motoneurons includes only information about moving the eyes. A: activity of a single motoneuron that (probably) innervates the inferior rectus muscle. The motoneuron has a pulse-step pattern of activity. The left column is for a downward saccade, and the right column is for an upward saccade. Vertical, dashed lines indicate onset and offset of the saccade. From Robinson (1970), with permission. B: activity of an excitatory burst neuron (EBN) in the left brain stem for leftward (top) and rightward (bottom) saccades (both have a vertical component). The EBN cell excites ipsilateral (ipsi) abducens motoneuron and fires prominently during ipsilateral saccades but has no activity during the hold period. contra, contralateral; H, horizontal; V, vertical. From Strassman et al. (1986), with permission. C: the neural integrator and the Robinson (1973) model of eye movements. In the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), the afferents in the head canal sense head-rotation velocity, providing a pulse-like input to the vestibular nucleus neurons. These neurons drive the eyes (in the opposite direction of the head movement), but their pulse is aided by the neural integrator, which also receives the pulse and sustains it through its input to the motoneurons. To generate a saccade, the burst generators produce a pulse, activating the motoneurons and moving the eyes to one side. The neural integrator receives this pulse and produces a step that sustains the motoneuron activity beyond the duration of the pulse, maintaining the eyes at the displaced position after the pulse has ended. D: Robinson (1973) hypothesized that control of saccades benefited from internal feedback of the neural integrator. The pulse generator received a desired displacement signal (Δθd), which it transformed into a pulse that depended on a real-time estimate of the current difference [] between the position of the eye and desired position. The neural integrator provided an estimate of current position and fed this signal back to the input of the pulse generator. When the pulse had pulled the eye to the desired location, the integrator’s output matched the desired position, which ended the pulse.