Significance

Adult stem cells maintain tissue integrity by producing new cells to replenish damaged cells during tissue homeostasis and in response to injury. Using Drosophila adult midgut as a model we show that midgut injury elicited by chemical feeding or bacterial infection stimulates the production of two bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) ligands (Dpp and Gbb) that are critical for the expansion of the intestinal stem cell (ISC) population and midgut regeneration. Interestingly, we find that BMP expression is inhibited by BMP signaling itself, and this autoinhibition is required for resetting ISC pool size to the homeostatic level after tissue repair. Our study suggests that transient expansion of the stem cell population through the dynamic regulation of niche signals serves as a strategy for regeneration.

Keywords: midgut, BMP, Dpp, stem cell, regeneration

Abstract

Many adult organs rely on resident stem cells to maintain homeostasis. Upon injury, stem cells increase proliferation, followed by lineage differentiation to replenish damaged cells. Whether stem cells also change division mode to transiently increase their population size as part of a regenerative program and, if so, what the underlying mechanism is have remained largely unexplored. Here we show that injury stimulates the production of two bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) ligands, Dpp and Gbb, which drive an expansion of intestinal stem cells (ISCs) by promoting their symmetric self-renewing division in Drosophila adult midgut. We find that BMP production in enterocytes is inhibited by BMP signaling itself, and that BMP autoinhibition is required for resetting ISC pool size to the homeostatic level after tissue repair. Our study suggests that dynamic BMP signaling controls ISC population size during midgut regeneration and reveals mechanisms that precisely control stem cell number in response to tissue needs.

Many organs, including Drosophila adult midguts, rely on resident stem cells to replace damaged cells during homeostasis and in response to injury (1). Upon injury, stem cells are transiently activated to increase their proliferation and differentiation to rapidly replenish lost cells. After tissue repair, stem cells return to their quiescent homeostatic state. The mechanisms underlying the dynamic change of stem cell behavior during regeneration/tissue repair remain poorly understood in most systems. In addition, whether injury alters stem cell division mode, for instance from asymmetric division to symmetric division, to adjust their population size as a strategy for efficient tissue repair remains largely unexplored.

Drosophila midgut has emerged as a powerful system to study stem cell biology in adult tissue homeostasis and regeneration (2–4). Intestine stem cells (ISCs) in adult midguts are localized at the basal side of the gut epithelium (5, 6). ISCs normally undergo asymmetric cell division to produce renewed ISCs and enteroblasts (EBs), the majority of which express Su(H)-lacZ and differentiate into enterocytes (ECs), whereas a small fraction express prospero (pros) and differentiate into enteroendocrine cells (Fig. 1A) (5–9). At a lower frequency, an ISC can undergo symmetric cell division to produce two ISCs or two EBs (10–12). The decision between ISC self-renewal and differentiation is controlled by Notch (N) signaling whereby N pathway activation inhibits ISC fate by promoting its differentiation into Su(H)-lacZ+ EB (5, 6, 13, 14). The asymmetric N signaling between ISC and Su(H)-lacZ+ EB is influenced by Par complex and integrins-directed asymmetric cell division and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling gradient (11, 12). After asymmetric cell division, the basally localized ISC daughter cell transduces higher levels of BMP signaling activity than the apically localized one and BMP signaling promotes ISC fate by antagonizing N pathway activity (12).

Fig. 1.

Bleomycin increases ISC pool size by promoting symmetric self-renewing division. (A) ISC lineage in Drosophila adult midguts. (B–G) PH3 or Dl staining in midguts treated with either sucrose (Suc; B, E) or bleomycin (Bleo; C, F) for 1 d. Quantification of PH3+ and Dl+ cells is shown in D and G, respectively. Three independent experiments were performed and 15 guts or areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are standard deviations (SDs). P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (H) Schematic drawing of an ISC division that produces differentially labeled daughter cells (RFP+ GFP− and RFP− GFP+) through FRT-mediated mitotic recombination. (I) Schematic drawings of differentially labeled twin clones generated by FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination of dividing ISCs. (J–O) Representative twin clones from midguts treated with sucrose or bleomycin. RFP and GFP expressions are shown in red and green, respectively. Three independent experiments were performed, and representative images are shown here. (P) Quantification of twin spots of different classes from midguts fed with sucrose or bleomycin: sucrose (n = 102, ISC/EB: 79%, ISC/ISC: 12%, EB/EB: 9%), bleomycin (n = 106, ISC/EB: 57%, ISC/ISC: 34%, EB/EB: 9%). Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Drosophila midguts undergo slow turnover under normal homeostasis but can activate regeneration programs leading to rapid cell proliferation and differentiation in response to tissue damage (15, 16). A number of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways including Insulin, Janus kinase-signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK-STAT), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Wnt, Hedgehog, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and Hippo (Hpo) pathways are found to be involved in the regulation of ISC proliferation (15–28); however, how ISC self-renewal and stem cell pool size are regulated in response to injury has been largely unexplored. In addition, how ISC activity returns to normal homeostasis after tissue repair has remained poorly understood.

In this study we explored how BMP signaling is dynamically regulated in response to tissue damage and what the functional consequence of such regulation is during Drosophila midgut regeneration. To do this, we examined the expression of two BMP ligands encoded by decapentaplegic (dpp) and glass bottom boat (gbb) in adult midguts injured by feeding adult flies with chemicals including bleomycin and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), which cause distinct tissue damages in adult midguts (15), or by bacterial infection. We found that feeding flies with bleomycin or infection with Pseudomonas entomorphila (PE), a gram-negative bacterium, increased the expression of both dpp and gbb in ECs. Our previous study suggested that EC-derived BMPs promoted ISC self-renewal by antagonizing N signaling in normal homeostasis (12). Consistent with this finding, we found that bleomycin and PE promoted symmetric self-renewing division, leading to an expansion of ISC pool size. We further showed that elevated BMP signaling is responsible for injury-induced symmetric self-renewing division and ISC expansion. We found that elevated BMP ligand production activated the BMP pathway both in precursor cells and in ECs. Interestingly, BMP pathway activation in ECs inhibited the expression of dpp and gbb. We provide evidence that this negative feedback regulation allows the midguts to reset the stem cell population size to the homeostatic level after tissue repair.

Results

Bleomycin Feeding Promotes Symmetric Self-Renewing Division of ISC.

Previous studies revealed that feeding flies with bleomycin, an anticancer drug that is widely used as a DNA-damaging agent in experimental systems, resulted in EC damage and elevated ISC proliferation through the activation of EGFR and JAK-STAT pathways (15, 18, 29). Immunostaining of midguts derived from bleomycin-fed adult females for the ISC marker Delta (Dl) and a mitotic cell marker phospho-histone 3 (PH3) revealed an increase in the number of Dl+ cells in addition to increased PH3+ cells (Fig. 1 B–G). Moreover, Dl+ cells often formed two- to three-cell clusters in bleomycin-treated guts, whereas in control guts Dl+ cells were mostly isolated and barely formed two-cell clusters (Fig. 1 E and F). Double labeling with the EB marker Su(H)-lacZ revealed that most Dl+ cells did not express Su(H)-lacZ in either control or bleomycin-treated guts (Fig. S1), suggesting that Dl staining faithfully marked the ISCs under these conditions. Of note, increased Dl+ cells were observed in both anterior and posterior regions of the midguts; however, for quantification, we focused on the posterior region (R4) of the midguts to minimize the variation (30). The increased number of Dl+ cells in bleomycin-fed guts suggests that stem cell population was expanded in response to tissue damage. Although inactivation of Hpo signaling pathway in precursor cells by expressing UAS-Wts-RNAi, which targets the Hpo pathway kinase Warts (Wts), dramatically increased the number of PH3+ cells, Wts RNAi only slightly increased Dl+ cell number (Fig. S2), suggesting that injury-induced ISC expansion is not simply due to increased ISC proliferation.

Fig. S1.

Dl and Su(H)-lacZ expression in bleomycin-treated midguts. (A–C) Dl and LacZ expression in midguts of Su(H)-lacZ; esgts > GFP treated with either sucrose (Suc; A and A′) or bleomycin (Bleo; B and B′) for 24 h. Arrows indicate Dl+ Su(H)-lacZ− cells and the asterisk indicates a Dl+ Su(H)-lacZ+ cell. Quantification of LacZ and Dl+ cells is shown in C. Three independent experiments were performed and 15 areas were examined for each sample per experiment. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Fig. S2.

Wts inactivation increases ISC proliferation but does not dramatically alter ISC number. (A–D) Dl or PH3 staining of control guts (A and B) and midguts expressing esgts > Wts-RNAi for 4 d (C and D). (E and F) Quantification of Dl+ or PH3+ cells in control guts or midguts expressing esgts > Wts-RNAi. Three independent experiments were performed and 10 guts or areas were examined for each sample per experiments. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. *P < 0.05. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

To determine whether bleomycin could change ISC/EB fate more definitively, we carried out two-color lineage tracing experiments in which the two ISC daughter cells and their descendants were labeled by RFP+ (red) and GFP+ (green), respectively, following FLP/FRT-mediated mitotic recombination (Fig. 1 H and I) (12). Adult flies of hs-flp; FRT82 ubi-RFP/FRT82 ubi-GFP were grown at 30 °C for 7 d and fed with sucrose or bleomycin for 1 d before clone induction by heat shock at 37 °C. After heat shock, flies were fed with sucrose (mock) or bleomycin for one more day and then recovered on normal food for 1–2 d before analysis. Consistent with previous reports (10–12, 31), the majority of twin spots (∼79%) from the control guts contained one multicellular clone and one single-cell clone, which were derived from asymmetric ISC/EB pairs (Fig. 1 J and P and Fig. S3), and only a small fraction of twin spots contained either two multicellular clones derived from symmetric ISC/ISC pairs (∼12%) or two single-cell clones derived from symmetric EB/EB pairs (∼9%) (Fig. 1 K, L, and P and Fig. S3). In bleomycin-fed guts, the twin spots derived from the symmetric ISC/ISC pairs were increased to 34% whereas those derived from the asymmetric ISC/EB pairs decreased to 57% (Fig. 1 M–P and Fig. S3). These results indicate that bleomycin increased ISC pool size by promoting the symmetric self-renewing ISC division.

Fig. S3.

Two-color twin spot clonal analysis of midguts treated with bleomycin. (A–F) Examples of the indicated classes of twin spots generated by heat-shock-induced FRT/FLP-mediated mitotic recombination in mock-treated (A–C) and bleomycin-treated midguts (D–F). GFP and RFP expressions are shown in green and red channels, respectively. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Bleomycin Feeding Increases BMP Expression in ECs and Pathway Activity in Precursor Cells.

Our previous study revealed that BMP signaling promotes ISC self-renewal in midguts under normal homeostasis as gain of function of BMP signaling increased ISC number, whereas loss of BMP signaling caused loss of ISCs due to their precautious differentiation (12). We therefore determined whether bleomycin promotes ISC self-renewal by altering BMP pathway activity. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) revealed that both dpp and gbb mRNAs were up-regulated in bleomycin-fed guts compared with control guts (Fig. 2A). ECs are the major source of BMP signal that regulates ISC self-renewal and GFP driven by dpp-Gal4 driver (dpp > GFP) was mainly expressed in ECs with high levels in discrete domains (R1, R3, and R5) along the anteroposterior (A/P) axis of midguts (Fig. 2 B and B′) (12, 30). We found that the domains of high dpp > GFP expanded along the A/P axis of midguts after adult flies were fed with bleomycin for 24 h (Fig. 2 C and C′). In control guts, the expression of dad-lacZ, a BMP pathway reporter gene, was asymmetric in pairs of precursor cells and relatively high in Dl+ cells (arrows in Fig. 2 D and D′) (12). In bleomycin-fed guts, however, many clusters of Dl+ cells exhibited a high level dad-lacZ expression (arrows in Fig. 2 E and E′), suggesting that bleomycin could increase BMP signaling activity in precursor cells. BMP signaling activity was also up-regulated in ECs as indicated by the increased phosphorylated mothers against dpp (pMad) levels (Fig. 2G compared with Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Bleomycin up-regulates BMP signaling to promote ISC expansion. (A) Relative mRNA levels of dpp and gbb determined by RT-qPCR from guts treated with sucrose (Suc) or bleomycin (Bleo) for the indicated time. (B–E′) dpp > GFP (B-C′) or dad-lacZ and Dl (D–E′) expression in midguts treated with sucrose or bleomycin for 24 h. (F–M) pMad (F–I) or Dl (J–M) staining of control (Con) or dpphr56/+ midguts treated with sucrose or bleomycin for 24 h. (N) Quantification of Dl+ cells in control and dpphr56/+ midguts. Three independent experiments were performed and 10 areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05. (O–R) Representative twin clones from control and dpphr56/+ midguts treated with sucrose or bleomycin. Three independent experiments were performed, and one representative image is shown here. (S) Quantification of twin spots of different classes from the indicated midguts: Con/Suc (n = 97, ISC/EB: 76%, ISC/ISC: 12%, EB/EB: 12%), Con/Bleo (n= 112, ISC/EB: 56%, ISC/ISC: 33%, EB/EB: 11%), dpphr56/+/Suc (n = 82, ISC/EB: 78% ISC/ISC: 9%, EB/EB: 13%), and dpphr56/+/Bleo (n = 108, ISC/EB: 68%, ISC/ISC:13%, EB/EB: 19%). Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. (T–W) DI staining of control guts or guts expressing two copies of UAS-Dpp-RNAi and UAS-Gbb-RNAi transgenes with Myo1Ats for 7 d in 30 °C and treated with sucrose or bleomycin for 24 h. (X) Quantification of Dl+ cells in control or Dpp and Gbb double-knockdown midguts. Three independent experiments were performed and 10 areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

We also examined whether BMP production in midguts was altered in other injury models. Feeding flies with DSS increased stem cell proliferation but only slightly increased Dl+ cell number (Fig. S4 A–D) (15, 18). Consistent with the subtle change in ISC number, DSS feeding did not significantly alter the expression of either dpp or gbb (Fig. S4E). By contrast, infection with PE increased the expression of both dpp and gbb and resulted in a large increase in the number of Dl+ cells as well as PH3+ cells (Fig. S4 F–L). Hence, the increase in ISC pool size correlates with an elevation in BMP production.

Fig. S4.

BMP up-regulation and ISC expansion are induced by PE infection but not by DSS feeding. (A, B, and F–I) Dl staining of midguts treated with sucrose (A and F), DSS (B), or infected by PE for 12 h (G), 16 h (H), or 24 h (I). (C, D, J, and K) Quantification of Dl+ or PH3+ cells in midguts treated with sucrose or DSS for 2 d, or infected with PE for the indicated time. Three independent experiments were performed and 15 areas or guts were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05. NS, not significant. (E and L) Relative levels of dpp and gbb mRNA determined by RT-qPCR from midguts treated with sucrose or DSS for 2 d (E) or infected with PE for the indicated time (L). Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05. NS, not significant. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Bleomycin Promotes ISC Self-Renewal Through BMP Signaling.

If injury increases ISC pool size through up-regulating the BMP pathway, we expect that reduction in the levels of BMP ligand would suppress bleomycin-induced increase in ISC number. We therefore used a temperature-sensitive dpp mutant allele, dpphr56, to reduce the dose of Dpp in heterozygotes (dpphr56/+). pMad staining confirmed that dpphr56/+ guts exhibited greatly reduced BMP pathway activity after bleomycin treatment (Fig. 2I, compared with Fig. 2G) although they exhibited comparable basal BMP pathway activity compared with control guts after mock treatment (Fig. 2H, compared with Fig. 2F). Importantly, dpp heterozygosity suppressed the formation of Dl+ cell clusters in bleomycin-fed guts, leading to a reduction in Dl+ cell number, although dpp heterozygosity did not affect the number of Dl+ cells in homeostatic guts (Fig. 2 J–N).

We then conducted two-color lineage tracing experiments to determine whether the observed reduction in Dl+ cell number in dpphr56/+ guts treated with bleomycin was due to altered ISC division mode. Control or dpphr56/+ adult flies containing FRT82 ubi-RFP/FRT82 ubi-GFP were grown at 30 °C for 7 d and then fed with sucrose or bleomycin for 1 d before clone induction by heat shock. After clone induction, the flies were fed with sucrose or bleomycin for 1 d and then raised on the normal food for 1–2 d before analysis (Fig. 2 O–R). In mock-treated guts, both control and dpphr56/+ exhibited a similar distribution of three classes of twin-spot clones (Fig. 2S); however, upon bleomycin treatment, dpphr56/+ guts contained twin-spot clones of the ISC/ISC class at reduced frequency (13%) compared with control guts (33%) but contained twin-spot clones of the EB/EB and ISC/EB classes at higher frequency (19% and 68%, respectively) than control guts, which contained twin-spot clones of the EB/EB and ISC/EB classes at 11% and 56%, respectively (Fig. 2S). Thus, reduction in the levels of BMP ligand altered the ISC division mode so that fewer ISCs underwent symmetric self-renewing division in response to injury.

To determine whether BMP up-regulation in ECs is required for bleomycin-induced ISC expansion, we knocked down both Dpp and Gbb in ECs by expressing USA-Dpp-RNAi [Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BL) no. 25782] and UAS-Gbb-RNAi (32) using an EC-specific Gal4 driver Myo1Ats (Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts). RT-qPCR confirmed that dpp and gbb mRNA levels were reduced in the double-knockdown guts after bleomycin treatment compared with control guts (Fig. S5 A and B). Furthermore, knockdown of both Dpp and Gbb in ECs also suppressed the formation of Dl+ cell clusters and reduced the overall number of Dl+ cells in bleomycin-treated guts (Fig. 2 U, W, and X), although it did not significantly affect Dl+ cell number in mock-treated guts (Fig. 2 T, V, and X). In addition to reduced ISC number, we also found that reduced BMP signal either in dpphr56/+ guts or in Dpp and Gbb double-knockdown guts resulted in a reduction in PH3+ cells in response to bleomycin treatment (Fig. S5 C–L). The reduction in the number of mitotic ISCs is at least in part due to a reduction in the ISC pool size in these guts.

Fig. S5.

Attenuation of BMP ligand production in ECs affects bleomycin-induced ISC proliferation. (A and B) Relative dpp (A) and gbb (B) mRNA levels measured by RT-qPCR in control guts or guts expressing two copies of UAS-Dpp-RNAi and UAS-Gbb-RNAi transgenes with Myo1Atstreated with sucrose (Suc) or bleomycin (Bleo). Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (C–F and H–K) PH3 staining in control guts (C, D, H, and I), dpp heterogeneous (dpphr56/+) guts (E and F), or guts expressing two copies of UAS-Dpp-RNAi and UAS-Gbb-RNAi transgenes with Myo1Atsfor 7 d (J and K) and treated with sucrose (C, E, H, and J) or bleomycin (D, F, I, and K) for 24 h. (G and L) Quantification of PH3+ cells in midguts of the indicated genotypes treated with sucrose or bleomycin. Three independent experiments were performed and 15 guts were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

It has been shown that Dpp is also produced in cells associated with midgut epithelia including trachea cells, visceral muscles, and hemocytes under homeostatic and/or stress conditions (33–36). However, knockdown of Dpp in these cells using tissue-specific Gal4 driver did not block bleomycin-induced increase in Dl+ cells (Fig. S6 A–I), suggesting that Dpp derived from these cells is not responsible for injury-induced ISC expansion. In addition, knockdown of Dpp in these cells did not significantly affect ISC proliferation in either control or bleomycin-treated guts (Fig. S6J).

Fig. S6.

Knockdown in Dpp in hemocytes, visceral muscle (VM), or trachea did not affect bleomycin-induced ISC expansion. (A–H′) Dl staining in control midguts (A–B′) or midguts with dpp knockdown in hemocytes using Hml-Gal4 (C–D′), VM using How-Gal4 (E–F′), or trachea cells using Btl-Gal4 (G–H′), treated with either sucrose (Suc; A, A′, C, C′, E, E′, G, and G′) or bleomycin (Bleo; B, B′, D, D′, F, F′, H, and H′) for 24 h. (I and J) Quantification of Dl+ cells (I) or pH3+ cells (J) in guts of the indicated genotypes. Three independent experiments were performed and nine areas or nine guts were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Up-Regulation of BMP Signaling Is Essential for Midgut Regeneration.

To determine whether damage-induced up-regulation of BMP plays a role in midgut regeneration, we used the esgF/O (esg-Gal4 tub-Gal80tsUAS-GFP; UAS-flp Act > CD2 > Gal4) system in which all cells in the ISC lineage are labeled by GFP after shifting temperature to 30 °C (16). Feeding adult flies with bleomycin induced a rapid turnover of midgut epithelia, as evidenced by the newly formed ECs (marked by GFP+ and large nuclei) 2 d after treatment, whereas mock-treated guts only contained GFP+ precursor cells at this stage (Fig. S7 A and B). Damage-induced epithelial turnover was greatly suppressed by lowering the dose of Dpp because the number of GFP+ ECs was greatly reduced in dpphr56/+ guts after bleomycin treatment (Fig. S7 C and D).

Fig. S7.

Reduction of Dpp dosage impedes midgut regeneration. (A–D) Three- to five-day-old control (A and B) or dpphr56/+ (C and D) flies expressing esgF/O were raised at 30 °C for 8 d and treated with sucrose (A and C) or bleomycin (B and D) for 2 d before immunostaining for GFP (green) and Hoechst (blue).

We next knocked down BMP signaling in stem cells and analyzed the consequence on ISC expansion and midgut regeneration in response to bleomycin treatment. To do this, we knocked down BMP type I receptors specifically in ISCs by expressing UAS-Tkv-RNAi [Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC) no. 105834], which targets both Thickveins (Tkv) and Saxophone (12), in midguts using esgtsSu(H)Gal80, referred to as esgtsSu(H)Gal80 > Tkv-RNAi, for 4 d before bleomycin feeding. Our previous study showed that prolonged depletion of BMP type I receptors in midgut progenitors by expressing esgts > Tkv-RNAi for 8 d resulted in stem cell loss (12); however, expression of esgtsSu(H)Gal80 > Tkv-RNAi for 4 d did not lead to significant ISC loss (Fig. 3 A, B, and K) but instead blocked bleomycin-induced ISC expansion (Fig. 3 F, G, and K). Similarly, RNAi of the type II receptor Punt (Put) for 4 d or Mad for 8 d did not lead to significant ISC loss but blocked bleomycin-induced ISC expansion (Fig. 3 C, D, H, I, and K). By contrast, overexpression of a constitutively active form of Tkv (TkvQ235D) for 5 d increased the number of Dl+ cells in both mock- and bleomycin-treated guts (Fig. 3 E, J, and K), which is consistent with our previous finding that excessive BMP signaling promotes ISC self-renewal (12).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of BMP signaling in ISCs impedes midgut regeneration. (A–J) Control midguts (A, F), midguts expressing UAS-Tkv-RNAi (B–G), UAS-Put-RNAi (C–H), UAS-Mad-RNAi with UAS-Dicer2 (D–I), or UAS-TkvQ235D (E–J) with esgts; Su(H)Gal80 at 30 °C were treated with either sucrose (A–E) or bleomycin (F–J) for 1 d before immunostaining to show the expression of Dl and GFP. Quantification of Dl+ cells is shown in K. Three independent experiments were performed and eight areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, NS: not significant. (L–T′) Lineage tracing experiments using His2A-CFP were performed in control (L, N, Q, Q′, S, and S′) or Tkv knockdown midguts (M, O, R, R′, T, and T′) treated with either sucrose or bleomycin for 1 d before immunostained with a GFP antibody. The guts were costaining with Hoechst to mark the nuclei (L–O) or a Pdm1 antibody to mark the ECs (Q–T′). Arrows indicate His2A-CFP+ with large nuclei (N and O) or His2A-CFP+ Pdm1+ Cells (Q–T′). (P) Quantification of CFP+ cells from experiments shown in L and M. Error bars are SDs. NS: not significant. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

To follow the ISC lineage, UAS-His2A-CFP was coexpressed using esgtsSu(H)Gal80. Because of its high stability, His2A-CFP can be inherited into ISC daughter cells to mark the newly formed ECs. In control guts, many ECs (marked by large nuclei and Pdm1 expression) were labeled by His2A-CFP 24 h after bleomycin treatment, whereas control guts fed with sucrose contained few, if any, His2A-CFP+ ECs (Fig. 3 N, S, and S′ compared with Fig. 3 L, Q, and Q′). By contrast, esgtsSu(H)Gal80 > Tkv-RNAi guts contained very few His2A-CFP+ ECs 24 h after bleomycin treatment (Fig. 3 O, T, and T′) although they exhibited no significant difference compared with control guts after mock treatment (Fig. 3 M, R, and R′ compared with Fig. 3 L, Q, Q′, and P). Taken together, these results suggest that inhibition of injury-induced ISC expansion by tuning down BMP signaling impairs EC regeneration.

BMP Signaling in ECs Inhibits BMP Ligand Production.

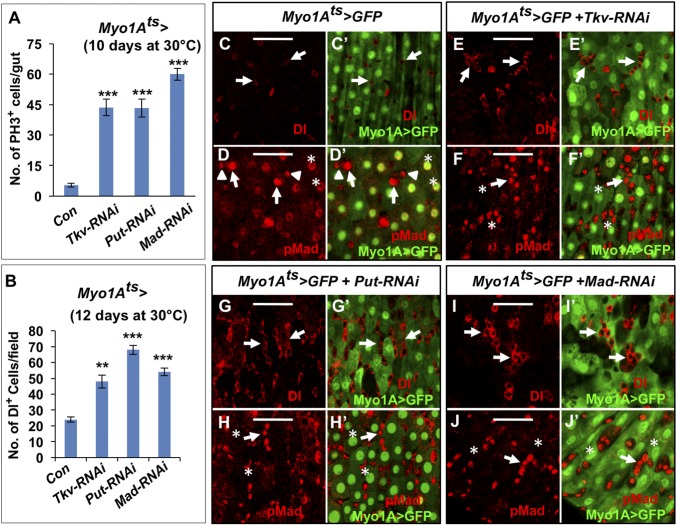

When we examined pMad levels in midguts we noticed that strong pMad signals were also present in ECs (Fig. 2 F and G) (12), suggesting that BMP pathway was active in these cells. To investigate the role of BMP signaling in ECs we blocked the pathway by expressing UAS-Tkv-RNAi, UAS-Put-RNAi, or UAS-Mad-RNAi with Myo1Ats. In addition to increased PH3+ cells (Fig. 4A) (12, 33), we also observed an increase in Dl+ cells when the BMP pathway was inactivated in ECs (Fig. 4 B, C′, E, E′, G, G′, I, and I′). These Dl+ cells often form clusters (arrows in Fig. 4 E, E′, G, G′, I, and I′), whereas in control guts Dl+ cells existed in isolation (arrows in Fig. 4 C and C′). Interestingly, we also observed many clusters of precursor cells (marked by small nuclei and Dl expression) exhibiting high levels of pMad staining when BMP signaling was inactivated in ECs (arrows in Fig. 4 F, F′, H, H′, J, and J′ and Fig. S8), whereas control guts contained many pairs of precursor cells exhibiting asymmetric pMad staining (Fig. 4 D and D′) (12). These observations suggest that blocking the BMP pathway in ECs caused ectopic BMP signaling in precursor cells, leading to increased ISC number. This noncell autonomous effect raised the possibility that BMP ligand production could be up-regulated in ECs when BMP signal transduction was blocked in these cells. Indeed, examining dpp and gbb expression by RT-qPCR (Fig. 5A), the dpp > GFP reporter (Fig. 5 B–D), and RNA in situ hybridization (Fig. S9 A–F′) revealed that blocking BMP signaling by Tkv RNAi up-regulated, whereas ectopic BMP pathway activation by expressing the constitutively active TkvQ235D down-regulated, the expression of both dpp and gbb. Thus, BMP ligand production in ECs is regulated by an autoinhibitory mechanism.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of BMP signaling in ECs promotes high levels of BMP signaling in precursor cells and ISC expansion. (A and B) Quantification of PH3+ (A) or Dl+ (B) cells in midguts of the indicated genotypes. Three independent experiments were performed and 20 guts or 10 areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (C–J) Dl or pMad staining of control guts (C–D′) or midguts expressing the indicated RNAi transgenes using Myo1Ats for 12 d (E–J′). Asterisks in D and D′ indicate pMad staining in ECs, which was lost in ECs when the indicated BMP pathway components were knocked down (asterisks in F, F′, H, H′, J, and J′). In control guts, Dl+ cells existed in isolation (arrows in C and C′) and pMad staining is asymmetric within pairs of precursor cells (arrows and arrowheads in D and D′). Midguts with individual BMP pathway components knocked down contained clusters of Dl+ cells (arrows in E, E′, G, G′, I, and I′) and clusters of precursor cells with high levels of pMad staining (arrows in F, F′, H, H′, J, and J′). Three independent experiments were performed, and representative images are shown. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Fig. S8.

Blocking BMP signaling in ECs results in up-regulation of BMP signaling in precursor cells. (A–B′′) Control guts (Myo1Ats > GFP; A–A′′) or guts with Mad knocked down in ECs (Myo1Ats > GFP + Mad-RNAi; B–B′′) for 12 d were immunostained for Dl, pMad, and DAPI. Arrows indicate Dl+ positive cells exhibiting high levels of pMad signal. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Fig. 5.

BMP signaling in EC inhibits the expression of dpp and gbb. (A) Relative levels of dpp and gbb mRNA determined by RT-qPCR from control guts (Myo1Ats) or guts expressing Myo1Ats > Tkv-RNAi for 10 d or Myo1Ats > TkvQ235D for 3 d. Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (B–D) GFP expression in control guts (dpp-Gal4ts/UAS-GFP; B) or guts expressing dpp-Gal4ts/UAS-GFP + UAS-Tkv-RNAi (C) or dpp-Gal4ts/UAS-GFP + UAS- TkvQ235D for 10 d (D). (E–H and J–M) Dl or PH3 staining in control midguts (Myo1Ats) or midguts expressing the indicated RNAi transgenes using Myo1Ats for 8 d. Hoechst staining marks the nuclei. (I and N) Quantification of Dl+ cells or PH3+ cells in midguts of the indicated genotypes. Three independent experiments were performed and 12 areas or guts were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (O) Relative levels of dpp and gbb mRNA determined by RT-qPCR from control guts (Myo1Ats) or guts expressing Myo1Ats > Tkv for 2 d and treated with sucrose (Suc) or bleomycin (Bleo) for 1 d. Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, **P < 0.01. (P–S) Dl staining of control guts (Myo1Ats) or guts expressing Myo1Ats > Tkv treated with sucrose (Suc) or bleomycin (Bleo) for one day. (T–U). Quantification of Dl+ cells or PH3+ cells in control guts (Myo1Ats) or guts expressing Myo1Ats > Tkv treated with sucrose (Suc) or bleomycin (Bleo). Three independent experiments were performed and 10 areas or 15 guts were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

Fig. S9.

BMP signaling regulates its own ligand production. (A–F′) gbb mRNA (red) was detected by RNA in situ hybridization in the middle or posterior region of midguts of the indicated genotypes. Myo1A > GFP expression marks ECs. (G–K) Midguts of the indicated genotypes were immunostained to show the expression of Dl. Quantification of Dl+ cells in the indicated genotype of midguts (K). Three independent experiments were performed and eight areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (L) Relative mRNA levels of dpp determined by RT-qPCR from guts of the indicated genotypes. Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test. NS: not significant.

A previous study suggested that blocking BMP signaling in ECs resulted in apoptosis (33). However, blocking cell death by coexpression of UAS-DIAP1 with UAS-Mad-RNAi in ECs did not affect Dpp up-regulation and stem cell expansion (Fig. S9 G–L), suggesting that up-regulation of BMP ligand production in ECs when BMP signaling was blocked is unlikely caused by cell death.

To determine whether the increase in ISC number when BMP signaling was inactivated in ECs was due to an up-regulation of Dpp and Gbb in these cells we coexpressed UAS-Dpp-RNAi and UAS-Gbb-RNAi with UAS-Mad-RNAi in ECs using Myo1Ats. We found that knockdown of BMP ligands greatly suppressed the ectopic ISC formation induced by Mad RNAi in ECs (Fig. 5 E–I). In addition, Dpp/Gbb double knockdown in ECs also suppressed the ectopic ISC proliferation due to Mad RNAi in these cells (Fig. 5 J–N). Taken together, these results suggest that BMP signaling in ECs inhibits the expression of both dpp and gbb, and that activation of ISC caused by inhibiting BMP signaling in ECs is, at least in part, due to elevated BMP production in these cells.

Elevated BMP Signaling in EC Blocked Injury-Stimulated BMP Production and ISC Expansion.

Because BMP signaling in ECs inhibits the expression of dpp and gbb, we expected that elevated BMP pathway activity in these cells would inhibit bleomycin-induced up-regulation of BMP production and thus the expansion of ISC population. To test this hypothesis we expressed UAS-Tkv in ECs using Myo1Ats for 2 d to boost BMP pathway activity, followed by mock or bleomycin treatment. We found that overexpression of Tkv in ECs attenuated bleomycin-stimulated up-regulation of dpp and gbb expression (Fig. 5O) and suppressed bleomycin-induced ISC expansion, as indicated by the reduction of Dl+ cells as well as PH3+ cells (Fig. 5 P–U). Hence, BMP autoinhibition in ECs can inhibit injury-stimulated stem cell expansion.

Dynamic Regulation of BMP Signaling During Tissue Regeneration.

Because bleomycin feeding stimulated the production of Dpp and Gbb that could activate BMP signaling not only in ISCs but also in ECs, and activation of BMP signaling in ECs could down-regulate the expression of dpp and gbb, we speculated that ligand production and BMP signaling may exhibit a dynamic change during regeneration. Indeed, we found that the expression of both dpp and gbb increased in midguts fed with bleomycin for 24 h, but their expression dropped below basal levels in guts treated for 48 h (Fig. 6A). Similarly, PE infection also induced a transient up-regulation of dpp and gbb expression (Fig. S4L).

Fig. 6.

BMP expression was dynamically regulated during midgut regeneration. (A) Relative dpp and gbb mRNA levels (bleomycin vs. sucrose treatment) were determined by RT-qPCR from guts treated with bleomycin or sucrose for the indicated time. Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (B–E′′) Midguts expressing dpp > GFP were treated with sucrose (B and B′′ and D and D′′) or bleomycin (C–C′′ and E–E′′) for 24 or 48 h, followed by immunostaining to show the expression of GFP (green) and pMad (red). DRAQ5 staining (blue) marks the nuclei. (F–G′′′) Midguts of the indicated genotype were treated with sucrose (F–F′′′) or bleomycin (G–G′′′) for 48 h, followed by immunostaining to show the expression of RFP (red), GFP (green), and pMad (blue). (Scale bars, 40 μm.)

To monitor BMP ligand expression and pathway activity simultaneously, we treated flies carrying dpp > GFP with sucrose or bleomycin for 24 or 48 h, followed by immunostaining with GFP and pMad antibodies. In mock-treated guts, pMad staining in posterior midguts was low and relatively even in ECs although dpp > GFP expression was not even (Fig. 6 B, B′′, D, and D′′). In guts treated with bleomycin for 24 h, both dpp > GFP and pMad were significantly up-regulated (Fig. 6 C and C′′ compared with Fig. 6 B and B′′). After bleomycin treatment for 48 h both dpp > GFP expression and pMad staining in ECs were very uneven, with some cells exhibiting high levels of GFP expression but undetectable pMad staining (arrows in Fig. 6 E and E′′) and others exhibiting high levels of pMad staining but undetectable dpp > GFP expression (arrowheads in Fig. 6 E and E′′). This reverse pattern of dpp > GFP expression and pMad staining is consistent with BMP ligand production’s being inhibited by BMP signaling in ECs.

To further explore the dynamic regulation of BMP signaling and ligand expression we carried out G-trace lineage tracing experiments using midguts carrying dpp-Gal4 Gal80ts; UAS-RFP UAS-flp ubi > stop > GFP in which cells used to express or currently expressing dpp were marked with GFP whereas cells currently expressing dpp were marked by red fluorescent protein (RFP) (37). In mock-treated guts, most ECs expressed both RFP and GFP and exhibited steady-state levels of pMad staining (Fig. 6 F and F′′′). In guts treated with bleomycin for 48 h, ECs exhibiting high levels of pMad did not express RFP, whereas ECs exhibiting low or undetectable levels of pMad expressed high levels of RFP (Fig. 6 G and G′′), consistent with the notion that BMP pathway activation inhibits BMP ligand expression. Some of the “pMad high” ECs also expressed high levels of GFP (arrowheads in Fig. 6 G and G′′), suggesting that these cells used to express dpp but high levels of BMP signaling in these cells blocked dpp expression at the time of detection. Only those GFP+ cells that exhibited low or undetectable pMad staining could reexpress dpp (GFP+ RFP+; arrows in Fig. 6 G and G′′). Hence, ECs seemed to dynamically switch on and off dpp expression in response to injury and this dynamic change is regulated through BMP autoinhibitory mechanism.

BMP Autoinhibition Resets ISC Pool Size to the Homeostatic Level.

We next asked what the functional significance of the dynamic regulation of BMP production in ECs is. One possibility is that BMP autoinhibition may provide a mechanism to down-regulate BMP ligand production and reset ISC pool size to the homeostatic level after tissue repair is achieved. We therefore carried out a pulse-chase experiment in which flies were fed with bleomycin for 24 h and then raised on normal food for another 24 h. ISC pool size (indicated by the number of Dl+ cells) and dpp expression (measured by RT-qPCR) were examined immediately after bleomycin feeding (24 h) or after a 24-h recovery on normal food (48 h) (Fig. 7A). We found that the number of ISC peaked at 24 h but dropped to basal level at 48 h (Fig. 7 B–F). The change in dpp expression followed the same dynamics (Fig. 7G). If the down-regulation of BMP production were responsible for the decrease in ISC number, then preventing the down-regulation of BMP production would sustain the expanded ISC population during regeneration. To achieve this, we attenuated BMP autoinhibition by partially blocking BMP signaling pathway in ECs by shifting Myo1Ats > Tkv-RNAi flies to 30 °C for 4 d before the pulse-chase experiment. We found that EC knockdown of Tkv for 4 d did not affect ISC number in mock-treated guts but dramatically increased the number of ISC+ cells at 48 h in bleomycin-fed guts (Fig. 7 H–L). RT-qPCR indicated that dpp mRNA levels decreased less dramatically at 48 h in Myo1Ats > Tkv-RNAi guts compared with control guts (Fig. 7M compared with Fig. 7G). These results suggest that down-regulation of BMP production in ECs may help to reset ISC pool size to the homeostatic level after tissue repair is accomplished.

Fig. 7.

BMP autoinhibition resets ISC homeostasis. (A) Scheme for the pulse-chase experiment. Three- to five-day-old adult flies were grown at 30 °C for 3 d, fed with sucrose (Suc; mock) or bleomycin (Bleo) for 24 h, and recovered on normal food for 24 h before analysis. (B–E and H–K) Control (Myo1Ats > GFP; B–E) flies or Tkv knockdown flies (Myo1Ats > GFP+Tkv-RNAi; H–K) were shifted to 30 °C for 3 d before treatment with sucrose (B, C, H, and I) or bleomycin (D, E, J, and K) for 24 h. Midguts were stained for Dl expression immediately after treatment (B, D, H, and J) or after a 24-h recovery (C, E, I, and K). (Scale bars, 40 μm.) (F and L) Quantification of Dl+ cells in the control (F) and Tkv knockdown (L) guts at the indicated time points. Three independent experiments were performed and 15 areas were examined for each sample. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (G and M) Relative dpp mRNA levels (bleomycin vs. sucrose treatment) determined by RT-qPCR from control (G) and Tkv knockdown (M) guts at the indicated time points after treatment. The level of dpp mRNA from mock-treated guts at each time point was set at 1. Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, **P < 0.01. (N) Quantification of twin spots of different classes from mock-treated guts (Suc, n = 105; ISC/EB: 76%, ISC/ISC: 13%, EB/EB: 11%), guts treated with bleomycin for 48 h (B24-hs-B24, n = 112; ISC/EB: 56%, ISC/ISC: 34%, EB/EB: 10%), or guts treated with bleomycin for 24 h and recovered on normal food for 24 h (B24-hs-R24, n = 110; ISC/EB: 38% ISC/ISC: 19%, EB/EB: 43%). Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (O) Quantification of Dl+, Su(H)-lacZ+, or double-positive cells in midguts treated with sucrose for 24 h (Suc), bleomycin for 24 h (Bleo 24h), or bleomycin for 24 h and recovered for 24 h (Bleo 24h Rec 24h). Three independent experiments were performed and eight areas were examined for each sample per experiment. Error bars are SDs. P values are from Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. (P) Dynamic BMP signaling in the regulation of ISC population size in respond to injury. Injury caused by bleomycin feeding or bacterial infection increased BMP production from ECs. Elevated BMP signaling in ISCs promote symmetric self-renewal division, leading to a transient expansion of ISC pool size. BMP signaling in ECs inhibits ligand production to reset stem cell homeostasis. BM, basement membrane; VM, visceral muscle. (Q) Dynamic BMP signaling results in changes in ISC division mode and transient expansion of ISCs, which produces more new ECs than the fixed division mode.

The dramatic decrease in dpp expression during recovery could cause ectopic ISC differentiation to EB, which may explain the observed decline in ISC number. To test this possibility, we examined ISC division mode by the two-color lineage tracing experiments described in Fig. 1 H–P. Adult flies of hs-flp; FRT82 ubi-RFP/FRT82 ubi-GFP were grown at 30 °C for 7 d and fed with bleomycin for 1 d before clone induction by heat shock at 37 °C. After heat shock, flies were fed with bleomycin for one more day (B24-hs-B24) and then transferred to normal food, or transferred to normal food immediately after heat shock for 24-h recovery (B24-hs-R24). After they were grown on normal food for another 2 d, midguts were dissected out for clonal analysis. Flies were also treated with sucrose (Suc) instead of bleomycin as a control. We found that ISC lineage clones generated during the recovery period contained more in the EB/EB class compared with those induced under continuous bleomycin treatment (43% vs. 10%; Fig. 7N and Fig. S10 A–C). The B24-hs-R24 group had reduced ISC/ISC and ISC/EB divisions compared with the B24-hs-B24 group (Fig. 7N and Fig. S10 D–I). We also examined the expression of Dl and Su(H)-lacZ in midguts immediately after bleomycin treatment (Bleo 24h) or after a 24-h recovery on normal food (Bleo 24h, Rec 24h). We found an increase in Su(H)-lacZ+ cell number with a concomitant decrease in Dl+ cell number in guts of the recovery group compared with the guts examined immediately after injury (Fig. 7O and Fig. S10 K–L′), which is consistent with the increased EB/EB division observed during recovery. Hence, the decline in ISC population size after recovery is likely due to an increased ISC to EB differentiation.

Fig. S10.

Increased ISC to EB differentiation during the recovery after bleomycin treatment. (A–I) Two-color lineage tracing experiments using mock-treated guts (Suc; A, D, and G), guts treated with bleomycin for 48 h (B24-hs-B24; B, E, and H), or guts treated with bleomycin for 24 h and recovered on normal food for 24 h (B24-hs-R24; C, F, and I). Clones were induced by 1-h heat shock at 37 °C after feeding the flies with sucrose or bleomycin for 24 h. Three independent experiments were performed, and representative images are shown in A–I with the frequency for each class of clones indicated. (J–L′) Dl and Su(H)-lacZ expression in midguts treated with sucrose for 24 h (J and J′), bleomycin for 24 h (K and K′), or bleomycin for 24 h and recovered for 24 h (L and L′).

Discussion

Injury can stimulate stem cell proliferation and even speed up lineage differentiation as a means to efficiently replace lost cells; however, whether tissue damage also transiently increases stem cell pool size as a regenerative strategy remains largely unexplored. Here we showed that tissue damage elicited by bleomycin feeding or PE infection increased ISC population by promoting symmetric self-renewing division of ISC in Drosophila midguts. We demonstrated that bleomycin and PE promoted ISC self-renewal by increasing the production of BMP ligands Dpp and Gbb, which function as niche signals for ISC self-renewal in the midgut (Fig. 7P). Interestingly, we found that the expression of BMP ligands was dynamically regulated and that transient up-regulation of BMP ligand production contributed to a transient expansion of ISC population during regeneration (Fig. 7Q). Furthermore, we uncovered a BMP autoinhibitory mechanism operating in ECs that restrains BMP ligand production and resets ISC pool size to the homeostatic level after tissue repair (Fig. 7 P and Q).

Our previous work demonstrated that EC-derived Dpp and Gbb serve as niche signals for ISC self-renewal during midgut homeostasis (12). Indeed, prolonged inactivation of Dpp or Gbb from ECs resulted in ISC loss (12). Although dpp expression was also detected in other cell types, including trachea and visceral muscles (33, 34), depletion of Dpp from these cells did not affect ISC self-renewal midgut homeostasis (12), nor did it affect bleomycin-induced ISC expansion or proliferation (Fig. S6). Our finding that gut epithelia function as a niche for stem cell self-renewal provides a framework for studying stem cell niche and its regulation because in most systems stem cell niches are derived from lineages distinct from the stem cells they support (38, 39). The employment of gut epithelia as a stem cell niche may provide a mechanism for direct communication between the niche and the environment, allowing the production of niche signal and stem cell pool size to be fine-tuned in response to external stimuli. Indeed, we found that epithelial damage caused by bleomycin feeding or bacterial infection increased the expression of both dpp and gbb, leading to increased ISC number following injury. The increased ISC number is not secondary to increased ISC proliferation, because accelerated ISC division induced by DSS or loss of Hpo signaling did not lead to a similar increase in ISC number. Rather, our lineage tracing experiments revealed that bleomycin treatment increased the proportion of ISCs that undergo symmetric self-renewing division. The switch from asymmetric to symmetric self-renewing division of ISCs is driven by increased BMP ligand production in ECs, followed by elevated BMP signaling activity in precursor cells. In support of this notion, we found that reduced BMP signaling suppressed injury-stimulated ISC expansion (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). In further corroboration with the notion that up-regulation of BMP signaling contributes to ISC expansion after injury, DSS feeding, which did not elevate BMP expression, did not dramatically alter ISC number. How BMP expression is stimulated by injury remains unresolved. Both bleomycin feeding and PE infection caused damage in ECs leading to their loss, whereas DSS feeding only affected basement membrane organization but did not cause EC loss (15, 16). Therefore, it is possible that EC damage triggers a stress response to stimulate BMP expression. Further study is required to determine the precise mechanism by which injury stimulates BMP production.

Because ISC is the only cell type that can undergo cell division, up-regulation of BMP production followed by a transient increase in ISC pool size may allow a more rapid generation of new cells to replenish the lost cells in response to bleomycin or PE-induced EC loss (Fig. 7Q). Indeed, reduction in the Dpp dosage in dpphr56 heterozygous flies or inhibition of BMP pathway in ISC greatly slowed down midgut turnover after bleomycin feeding (Fig. 3). Previous studies revealed that BMP signaling also promoted EB to EC differentiation as loss of BMP signaling slowed down, whereas ectopic activation of BMP pathway in EBs accelerated their differentiation to ECs (12, 35). Hence, up-regulation of BMP signaling may play a dual role in midgut regeneration by transiently increasing ISC number and stimulating terminal differentiation from EB to EC. Tissue damage up-regulates several other signaling pathways including JAK-STAT, EGFR, and Wnt pathways, which contribute to tissue regeneration mainly by stimulating ISC proliferation (4). Although our current study suggests that damage-stimulated BMP signaling mainly promotes ISC self-renewal, it remains to be explored whether BMP signaling exhibits cross-talk with these mitogenic signaling pathways in tissue regeneration.

Stem cell activity is only transiently up-regulated in response to acute injury, and after tissue repair stem cell activity needs to return to the homeostatic level. The mechanism underlying the reset of stem cell homeostasis remains poorly understood. We found that BMP expression is dynamically regulated during midgut regeneration. After a 24-h recovery from bleomycin treatment the expression of Dpp and Gbb was greatly reduced and the number of ISC returned to the homeostatic level (Fig. 7). Similarly, PE infection also induced a transient up-regulation of BMP accompanied by a transient expansion of ISC number (Fig. S4), suggesting the existence of a feedback mechanism to reset the stem cell number. Interestingly, we found that the BMP pathway can regulate the production of its own ligand through an autoinhibitory mechanism operating in ECs (Fig. 7P). Inhibition of BMP signaling in ECs resulted in increased expression of both dpp and gbb as well as increased ISC number, which disrupted the normal tissue homeostasis (Fig. 4). Furthermore, interfering with BMP autoinhibition attenuated the down-regulation of BMP production and sustained the expansion of ISC population, thus preventing midguts from returning to the normal homeostasis after repair (Fig. 7). Hence, the negative feedback loop of BMP signaling pathway provides a self-regulated mechanism to keep the production of niche signals in check during tissue homeostasis and regeneration. In addition, the dynamic regulation of BMP ligand production may provide a mechanism to modulate ISC population size according to tissue needs.

The mechanism revealed by our study is likely to be used in other settings. For example, Wnt7a expression was up-regulated during skeletal muscle regeneration, and because ectopic Wnt signaling could promote symmetric self-renewing of satellite stem cells in vitro and expand the stem cell pool in vivo (40) it is likely that injury-induced up-regulation of Wnt7a may result in a transient expansion of satellite stem cells to enhance muscle regeneration. It has been observed that Drosophila ISCs can alter their cell division mode in response to change in nutrient but the underlying mechanism remains poorly understood (10). It would be interesting to determine whether nutrient-regulated ISC plasticity also involves a dynamic regulation of BMP signaling.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Genetics and Transgenes.

Transgenic lines included UAS-Tkv-RNAi (VDRC no. 105834); UAS-Put-RNAi (VDRC no. 107071, second chromosome insertion, and VDRC no. 37279, third chromosome insertion); UAS-mad-RNAi (VDRC no. 12635); UAS-Dpp-RNAi (BL no. 33628 is a strong line whereas BL no. 25782 is a weak line) (12); UAS-Gbb-RNAi (32); and UAS-Wts-RNAi (VDRC no.106174). Transgenes included UAS-TkvQ235D (41); dad-lacZ (BL no. 10305); Dpp-Gal4 (42); UAS-Tkv, UAS-DIAP1, UAS-Dicer2, tub-Gal80ts, Myo1A-Gal4, UAS-His2ACFP, G-Trace (BL no. 28280); esg-Gal4, Su(H)-Gal4, Su(H) Gbe-lacZ (Su(H)-lacZ), How-Gal4, Btl-gal4, and Hml-Gal4 (flybase); and esgF/O: w; esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP; UAS-FLP act > CD2 > Gal4/+ (16). Mutants included dpphr56, a temperature-sensitive allele of dpp (Flybase). For experiments involving dpphr56, fly stocks were crossed and cultured at 18 °C until the pupae stage and then transferred to a 30 °C incubator to inactivate dpphr56. Nine-day-old dpphr56/+ adult flies grown at 30 °C were used for treatment. For twin spot clonal analysis, 5- to 10-d-old female adult flies were treated with sucrose or bleomycin for 1 d and then subjected to heat shock in empty vials for 1 h in a 37 °C water bath. After clone induction, flies were treated with sucrose or bleomycin for one more day and then transferred to vials containing fresh cornmeal food and raised at 30 °C for 1–2 d before dissection and immunostaining. For experiments involving tubGal80ts, crosses were set up and cultured at 18 °C to restrict Gal4 activity. Two- to three-day-old F1 adult flies were shifted to 30 °C for the indicated periods of time to inactivate Gal80ts, allowing Gal4 to activate UAS transgenes.

Feeding Experiments.

In general, 5- to 10-d-old female adult flies were used for feeding experiments. Flies were cultured in an empty vial containing a piece of 2.5- × 3.75-cm chromatography paper (Fisher) wet with 5% (wt/vol) sucrose solution as feeding medium (mock treatment) or with 25 μg/mL bleomycin or 5% (wt/vol) DSS dissolved in 5% (wt/vol) sucrose for one or more days at 30 °C. PE infection was carried out as previously described (16).

Immunostaining.

Female flies were used for gut immunostaining in all experiments. The entire gastrointestinal tract was taken and fixed in 1× PBS plus 8% EM-grade formaldehyde (Polysciences) for 2 h. Samples were washed and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies in a solution containing 1× PBS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.1% Triton X-100. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Delta (DSHB), 1:100; rabbit anti-LacZ (MP Biomedicals), 1:1,000; rabbit and mouse anti-PH3 (Millipore), 1:1,000; goat anti-GFP (Abcam), 1:1,000; mouse anti-pMad antibody (43), 1:300; DRAQ5 (Cell Signaling Technology), 1:5,000; and Hoechst (Life Technologies), 1:500. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:400 (Jackson ImmunoResearch and Invitrogen). Guts were mounted in 70% glycerol and imaged with a Zeiss confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710 inverted confocal) using 10×, 20×, or 40× oil objectives (imaging medium: Zeiss Immersol 518F). The acquisition and processing software was Zeiss LSM Image Browser, and image processing was done in Adobe Photoshop CC.

RNA in Situ Hybridization in the Adult Midguts.

RNA FISH in the midgut was performed as described (44). Forty-eight 20-mer DNA oligos complementing the coding region of the target genes (gbb) were designed and labeled with a fluorophore (https://www.biosearchtech.com/). For RNA in situ hybridization, the midguts were first dissected and fixed in 8% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for overnight, followed by washing with PBS and Triton X-100 (0.1%) three times (15 min each). The samples were further permeabilized in 70% ethanol at 4 °C overnight. The hybridization was performed according to the online protocol (https://www.biosearchtech.com/support/resources/stellaris-protocols).

RT-qPCR.

Total RNA was extracted from 10 female guts using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (74134; Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). RT-qPCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green System (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences used are 5′-gtgcgaagttttacacacaaaga-3′ and 5′-cgccttcagcttctcgtc-3′ (for dpp) and 5′-cgctggaactctcgaaataaa-3′ and 5′-ccacttgcgatagcttcaga-3′ (for gbb). RpL11 was used as a normalization control. Relative quantification of mRNA levels was calculated using the comparative CT method.

SI Materials and Methods

Genotypes Used in Main-Text Figures.

In Fig. 1 the genotypes used are as follows. (J–O) yw hsflp; FRT82B ubi-GFP/FRT82B ubi-RFP.

In Fig. 2 the genotypes used are as follows. (B–C′) yw; UAS-GFP/+; dpp-Gal4/+. (D–E′) yw; dad-lacZ. (F, G, J, K) yw. (H, I, L, M) dpphr56/+. (O, P) yw hsflp; FRT82B ubi-GFP/FRT82B ubi-RFP. (Q, R) yw hsflp; dpphr56/+; FRT82B ubi-GFP/FRT82B ubi-RFP. (T, U) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (V, W) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-Dicer2; UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi/UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi.

In Fig. 3 the genotypes used are as follows. (A, F) esg-Gal4Gal80tsUASGFP/+; Su(H)GBE:Gal80/+. (B, G) esg-Gal4Gal80tsUASGFP/UAS-TKV-RNAi;Su(H)GBE:Gal80/+. (C, H) esg-Gal4Gal80tsUASGFP/UAS-Put-RNAi;Su(H)GBE:Gal80/ UAS-Put-RNAi. (D, I) esg-Gal4Gal80tsUASGFP/UAS-Dicer2,UAS-Mad-RNAi;Su(H)GBE:Gal80/ +. (E, J) esg-Gal4Gal80tsUASGFP/+;Su(H)GBE:Gal80/ UAS-TKVCA. (L, N, Q, Q′, S, S′) esg -Gal4Gal80ts /+; Su(H)GBE:Gal80/UAS-His2ACFP. (M, O, R, R′, T, T′) esg -Gal4Gal80ts/UAS-TKV-RNAi; Su(H)GBE:Gal80/UAS-His2ACFP.

In Fig. 4 the genotypes used are as follows. (C–D′) Myo1A-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP.(E–F′) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Tkv-RNAi; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (G–H′) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Put-RNAi; tub-Gal80tsUAS-GFP/UAS-Put-RNAi. (I–J′) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Dicer2 UAS-Mad-RNAi; tub-Gal80tsUAS-GFP.

In Fig. 5 the genotypes used are as follows. (B) yw; UAS-GFP tub-Gal80ts/+; dpp-Gal4/+. (C) yw; UAS-GFP tub-Gal80ts/UAS-Tkv-RNAi; dpp-Gal4/+. (D) yw; UAS-GFP tub-Gal80ts; dpp-Gal4/UAS-TkvQ235D. (E, J) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80 ts UAS-GFP. (F, K) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-Dicer2; UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi/UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi. (G, L) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-Dicer2 UAS-Mad-RNAi. (H, M) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-Dicer2 UAS-Mad-RNAi; UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi/UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi. (P, Q) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (R, S) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-TKV.

In Fig. 6 the genotypes used are as follows. (B–E′′) yw; UAS-GFP tub-Gal80ts/+; dpp-Gal4/+. (F–G′′′) yw; tub-Gal80ts;dpp-Gal4/UAS-RFP UAS-Flp ubi > stop > GFP.

In Fig. 7 the genotypes used are as follows. (B–E) Myo1A-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (H–K) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Tkv-RNAi; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP.

Genotypes Used in Supporting Information Figures.

In Fig. S1 the genotypes used are as follows. (A–B′) Su(H) Gbe-lacZ; esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP.

In Fig. S2 the genotypes used are as follows. (A, B) esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (C, D) esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-Wts-RNAi.

In Fig. S3 the genotypes used are as follows. (A–F) yw hsflp;FRT82B ubi-GFP/FRT82B ubi-RFP.

In Fig. S4 the genotypes used are as follows. (A, B, F–I) yw.

In Fig. S5 the genotypes used are as follows. (C, D) yw. (E, F) dpphr56/+. (H, I) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (J, K) Myo1A-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-Dicer 2; UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi/UAS-Dpp-RNAi UAS-Gbb-RNAi.

In Fig. S6 the genotypes used are as follows. (A–B′) yw. (C–D′) Hml-Gal4/UAS-Dicer2; Gal80ts UAS-Dpp-RNAi. (E–F′) Gal80ts/UAS-Dicer2; HowGal4/UAS-Dpp-RNAi. (G–H′) Btl-Gal4/UAS-Dicer2; Gal80ts /UAS-Dpp-RNAi.

In Fig. S7 the genotypes used are as follows. (A, B) w; esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP; UAS-FLP act > CD2 > Gal4/+. (C, D) w; esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/dpphr56; UAS-FLP act > CD2 > Gal4/+.

In Fig. S8 the genotypes used are as follows. (A–A′′) Myo1A-Gal4/+; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/+. (B–B′′) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Dicer2UAS-Mad-RNAi; tub-Gal80 ts UAS-GFP/+.

In Fig. S9 the genotypes used are as follows. (A–B′) Myo1A-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (C–D′) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Tkv-RNAi; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP. (E–F′) Myo1A-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/UAS-TkvQ235D. (G) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Dicer2; Gal80ts/+. (H) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Mad-RNAi UAS-Dicer2; Gal80ts/+. (I) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Dicer2; Gal80ts/UAS-DIAP1. (J) Myo1A-Gal4/UAS-Mad-RNAi UAS-Dicer2; Gal80ts/UAS-DIAP1.

In Fig. S10 the genotypes used are as follows. (A–I) yw hsflp; FRT82B ubi-GFP/FRT82B ubi-RFP. (J–L′) Su(H) Gbe-lacZ; esg-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts UAS-GFP/+.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Peter ten Dijke, Steven Hou, and Huaqi Jiang, Vienna Drosophila Resource Center, and Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for fly stocks and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies. This work is supported National Institutes of Health Grant GM118063 and Welch Foundation Grant I-1603. J.J. is a Eugene McDermott Endowed Scholar in Biomedical Science at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617790114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Biteau B, Hochmuth CE, Jasper H. Maintaining tissue homeostasis: Dynamic control of somatic stem cell activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(5):402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casali A, Batlle E. Intestinal stem cells in mammals and Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(2):124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang H, Edgar BA. Intestinal stem cell function in Drosophila and mice. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22(4):354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang H, Tian A, Jiang J. Intestinal stem cell response to injury: Lessons from Drosophila. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(17):3337–3349. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micchelli CA, Perrimon N. Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature. 2006;439(7075):475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohlstein B, Spradling A. The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2006;439(7075):470–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biteau B, Jasper H. Slit/Robo signaling regulates cell fate decisions in the intestinal stem cell lineage of Drosophila. Cell Reports. 2014;7(6):1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beehler-Evans R, Micchelli CA. Generation of enteroendocrine cell diversity in midgut stem cell lineages. Development. 2015;142(4):654–664. doi: 10.1242/dev.114959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng X, Hou SX. Enteroendocrine cells are generated from stem cells through a distinct progenitor in the adult Drosophila posterior midgut. Development. 2015;142(4):644–653. doi: 10.1242/dev.113357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien LE, Soliman SS, Li X, Bilder D. Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell. 2011;147(3):603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulas S, Conder R, Knoblich JA. The Par complex and integrins direct asymmetric cell division in adult intestinal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(4):529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian A, Jiang J. Intestinal epithelium-derived BMP controls stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila adult midgut. eLife. 2014;3:e01857. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohlstein B, Spradling A. Multipotent Drosophila intestinal stem cells specify daughter cell fates by differential notch signaling. Science. 2007;315(5814):988–992. doi: 10.1126/science.1136606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardin AJ, Perdigoto CN, Southall TD, Brand AH, Schweisguth F. Transcriptional control of stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila intestine. Development. 2010;137(5):705–714. doi: 10.1242/dev.039404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(1):49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang H, et al. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. 2009;137(7):1343–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchon N, Broderick NA, Chakrabarti S, Lemaitre B. Invasive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2009;23(19):2333–2344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1827009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren F, et al. Hippo signaling regulates Drosophila intestine stem cell proliferation through multiple pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(49):21064–21069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012759107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WC, Beebe K, Sudmeier L, Micchelli CA. Adenomatous polyposis coli regulates Drosophila intestinal stem cell proliferation. Development. 2009;136(13):2255–2264. doi: 10.1242/dev.035196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Grenley MO, Bravo MJ, Blumhagen RZ, Edgar BA. EGFR/Ras/MAPK signaling mediates adult midgut epithelial homeostasis and regeneration in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(1):84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordero JB, Stefanatos RK, Scopelliti A, Vidal M, Sansom OJ. Inducible progenitor-derived Wingless regulates adult midgut regeneration in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2012;31(19):3901–3917. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amcheslavsky A, Ito N, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tuberous sclerosis complex and Myc coordinate the growth and division of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(4):695–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karpowicz P, Perez J, Perrimon N. The Hippo tumor suppressor pathway regulates intestinal stem cell regeneration. Development. 2010;137(24):4135–4145. doi: 10.1242/dev.060483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu N, et al. EGFR, Wingless and JAK/STAT signaling cooperatively maintain Drosophila intestinal stem cells. Dev Biol. 2011;354(1):31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw RL, et al. The Hippo pathway regulates intestinal stem cell proliferation during Drosophila adult midgut regeneration. Development. 2010;137(24):4147–4158. doi: 10.1242/dev.052506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biteau B, Jasper H. EGF signaling regulates the proliferation of intestinal stem cells in Drosophila. Development. 2011;138(6):1045–1055. doi: 10.1242/dev.056671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staley BK, Irvine KD. Warts and Yorkie mediate intestinal regeneration by influencing stem cell proliferation. Curr Biol. 2010;20(17):1580–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian A, et al. Injury-stimulated Hedgehog signaling promotes regenerative proliferation of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2015;208(6):807–819. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201409025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren F, et al. Drosophila Myc integrates multiple signaling pathways to regulate intestinal stem cell proliferation during midgut regeneration. Cell Res. 2013;23(9):1133–1146. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchon N, et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of adult midgut compartmentalization in Drosophila. Cell Reports. 2013;3(5):1725–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Navascués J, et al. Drosophila midgut homeostasis involves neutral competition between symmetrically dividing intestinal stem cells. EMBO J. 2012;31(11):2473–2485. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballard SL, Jarolimova J, Wharton KA. Gbb/BMP signaling is required to maintain energy homeostasis in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2010;337(2):375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Zhang Y, Han L, Shi L, Lin X. Trachea-derived dpp controls adult midgut homeostasis in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2013;24(2):133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo Z, Driver I, Ohlstein B. Injury-induced BMP signaling negatively regulates Drosophila midgut homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2013;201(6):945–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, et al. Dpp/Gbb signaling is required for normal intestinal regeneration during infection. Dev Biol. 2015;399(2):189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta D, et al. Regional cell-specific transcriptome mapping reveals regulatory complexity in the adult Drosophila midgut. Cell Reports. 2015;12(2):346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans CJ, et al. G-TRACE: Rapid Gal4-based cell lineage analysis in Drosophila. Nat Methods. 2009;6(8):603–605. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Losick VP, Morris LX, Fox DT, Spradling A. Drosophila stem cell niches: A decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev Cell. 2011;21(1):159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones DL, Wagers AJ. No place like home: Anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(1):11–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Grand F, Jones AE, Seale V, Scimè A, Rudnicki MA. Wnt7a activates the planar cell polarity pathway to drive the symmetric expansion of satellite stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh SK, Scott MP, Sarnow P. Homeotic gene Antennapedia mRNA contains 5′-noncoding sequences that confer translational initiation by internal ribosome binding. Genes Dev. 1992;6(9):1643–1653. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy S, Hsiung F, Kornberg TB. Specificity of Drosophila cytonemes for distinct signaling pathways. Science. 2011;332(6027):354–358. doi: 10.1126/science.1198949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Persson U, et al. The L45 loop in type I receptors for TGF-beta family members is a critical determinant in specifying Smad isoform activation. FEBS Lett. 1998;434(1-2):83–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat Methods. 2008;5(10):877–879. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]