Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tau immunotherapy has emerged as a promising approach to clear tau aggregates from the brain. Our previous findings suggest that tau antibodies may act outside and within neurons to promote such clearance.

METHODS

We have developed an approach using flow cytometry, a human neuroblastoma cell model overexpressing tau with the P301L mutation, and paired helical filament (PHF)-enriched pathological tau to effectively screen uptake and retention of tau antibodies in conjunction with PHF.

RESULTS

The flow cytometry approach correlates well with Western blot analysis to detect internalized antibodies in naïve and transfected SH-SY5Y cells (r2=0.958, and r2=0.968, p=0.021 and p=0.016, respectively). In transfected cells, more antibodies are taken up/retained as pathological tau load increases, both under co-treated conditions and when the cells are pre-treated with PHF prior to antibody administration (r2=0.999 and r2=0.999, p=0.013 and p=0.011, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This approach allows rapid in vitro screening of antibody uptake and retention in conjunction with pathological tau protein before more detailed studies in animals or other more complex model systems.

INTRODUCTION

Antibody immunotherapies are a major focus of treatment approaches for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases [1–3]. Our laboratory has pioneered targeting pathological tau proteins for clearance with active and passive immunotherapies for Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies [4,5], which have been confirmed and extended by multiple groups over the last several years [6–33]. With numerous potential tau epitopes to target, as well as various antibody isotypes and effector mechanisms to consider, it has become a daunting task to pre-screen potential candidate antibodies to test in animal models.

We have developed an approach using flow cytometry and a human neuroblastoma cell model to detect internalization of tau antibodies and paired helical filament (PHF)-enriched pathological tau protein. Our findings show that this approach correlates very well with Western blot detection of tau antibody uptake, and confirms such uptake observed in different model systems [4,13,14,21,28,34]. This rapid and highly quantitative approach is an effective means to screen antibody internalization with or without pathological tau, which can be detected in a similar manner. Tau antibodies can in theory lead to tau clearance extra- and/or intracellularly. To target both pools of the pathological protein simultaneously is likely more efficacious. Hence, it is important to be able to quickly and quantitatively screen antibody’s ability to enter cells, which varies and likely depends primarily on its charge [1].

Overall, such multiplexing approach to detect antibodies and pathological targets in cells has great potential to be used with conventional techniques to better understand the mechanism of action of prospective immunotherapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

METHODS

Paired helical filament (PHF) Protein Preparation

Human brain slices were homogenized and prepared in buffer (pH 6.5; 0.75 M NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid) along with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatant was subsequently centrifuged in an ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The pellet was then re-suspended in PHF extraction buffer containing sucrose (10 mM Tris; 10% sucrose; 0.85 M NaCl; and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) and spun at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was re-extracted in the sucrose buffer at the same low-speed centrifugation. The supernatants from both sucrose extractions were pooled and subjected to 1% sarkosyl solubilization by stirring at ambient temperature, then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C in a Beckman 60 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). The resulting pellet was re-suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), using 0.5 µL of buffer for each milligram of initial weight of brain sample protein, and designated the PHF preparation.

Tau Antibody and Fluorescence Labeling

In this study we used the tau antibody, 6B2G12 (6B2), which detects Ser396/404 tau epitope, and has previously been characterized, by our laboratory [14,35]. The antibody and the PHF-enriched brain fraction were tagged with Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 647, respectively, using protein labeling kits, as detailed in the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Cell Culture

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells obtained from ATCC were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and pcDNA3.1(+) P301L hTau 4R0N with gentomycin (G418) selection. Naive and transfected cells were cultured in complete media (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with glutamax (Invitrogen), 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10,000 Units/mL Penicillin, and 10,000 µg/mL streptomycin). Transfected cells addtionally contained 200 µg/mL gentomycin. Cells were plated at 4×102 cells/mm2, allowed to recover for 3 days before each experiment, and grown in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. For dose response experiments, naive and transfected cells were treated with increasing doses of 6B2 antibody (0–60 µg/mL) for 24 h. For co- and pre-treatments, transfected cells were either pre-treated with increasing levels of tagged PHF (0.1–10 µg/mL) for 24 h, then washed several times to remove remaining extracellular PHF, and subsequently incubated with tagged 6B2 tau antibody (5 µg/mL) for another 24 h or co-incubated with both for 24 h.

Flow Cytometry

All cells analyzed with flow cytometry were incubated with tagged 6B2 antibody and/or tagged PHF. Prior to measurements, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, re-suspended in ice-cold complete media, and then spun down and pelleted at 200 × g for 5 minutes. Supernatant was discarded and pelleted cells were then resuspended in ice-cold PBS, and put through a 0.2 micron filter (PARTEC). To quench any surface bound fluoresence, trypan blue was added to each sample at a final concentration of 0.02% (w/v) (Sigma Aldrich) and the sample was placed on ice. Samples were analyzed using flow cytometery (LSRII, Becton Dickinson) to a count of 10,000 cells per sample, and were gated for viable and singlet cell populations. Cells were further analyzed using FlowJo for either Alexa Fluor 488 and/or 647 positive cells. Median fluoresence intensity (MFI) values were obtained for both fluorescent signals.

Western Blot

All cells analyzed using western blot were incubated with non-tagged 6B2 antibodies and/or PHF. All samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer and prepared as described previously [14]. Samples were boiled and loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, electrophoresed, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were blocked in 5% milk with 0.1% TBS-T. Blots were then probed for total tau (Dako polyclonal antibody), phospho-tau (PHF-1 monoclonal antibody) or GAPDH (Abcam polyclonal antibody) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed and then probed with anti-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated rabbit or mouse secondary antibody (Pierce) for 1 h. For antibody uptake detection, membranes were incubated with an anti-mouse IgG1 HRP-conjugated secondary antibody with specificity against the heavy chain (Bethyl Laboratories), and signal was detected with an ECL substrate (Thermo Scientific). Images of immunoreactive bands were then acquired and quantified using the Fuji LAS-4000 imaging system.

Immunocytochemistry

Coverslips were coated with poly-D-lysine. Cells were plated onto coverslips at at 4×102 cells/mm2, allowed to recover for 3 days, then washed, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After subsequent washing, cells were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with 5% BSA, which were both in PBS. A total tau primary antibody, CP27, was incubated overnight at 4°C at 1:200 dilution. Cells were then washed, incubated in Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated mouse secondary antibody for one h at room temperature, and washed again. Finally before mounting, cells were incubated with Hoechst nuclear stain (Invitrogen). Fluorescent imaging of cells was performed on a Nikon C1 confocal system.

Live Cell Imaging

Chamber glasses (Nunc) were coated with Pluripro protein matrix (Cell Guidance Systems) as directed by the manufacturer. Cells were plated onto these glasses at 4×102 cells/mm2, allowed to recover for 3 days, then treated with PHF and/or 6B2 tau antibody as described above, followed by washing with complete media. Prior to imaging, cells were incubated with Lysotracker Red, an endosomal-lysosomal dye, and Hoechst nuclear dye as directed by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Cells were then washed and finally placed into complete media with no phenol red-DMEM and HEPES (Invitrogen). Chamber glasses were then analyzed using an Applied Precision PersonalDV live-cell imaging system in an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope with a 60× objective, with heating at 37°C. DeltaVision filter setting (DAPI, FITC, TRITC, and Cy5) corresponded to fluorescent signals from the respective dyes (Hoechst, Alexa Fluor 488, Lysotracker Red, and Alexa Fluor 647).

Immuno-Electron Microscopy

PHF preparations were placed on 300 mesh copper or nickel electron microscope grids. Grids were transferred to drops of 1% PBS-BSA and blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature, then incubated in PHF-1 primary antibody with blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The grid was then washed with PBS, reacted with gold-IgG complex secondary antibody, washed again with PBS, then stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate and washed with sterile distilled water, and blotted dry. Grids were visualized and images were taken with a Phillips CM12 Cryoelectron microscope.

Statistics

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6. Pearson correlation coefficients were generated for western blot vs. flow cytometry data. Other data sets were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test or Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

RESULTS

Tau antibody uptake into neuroblastoma cells measured by flow cytometry correlates very well with uptake detected by Western blot

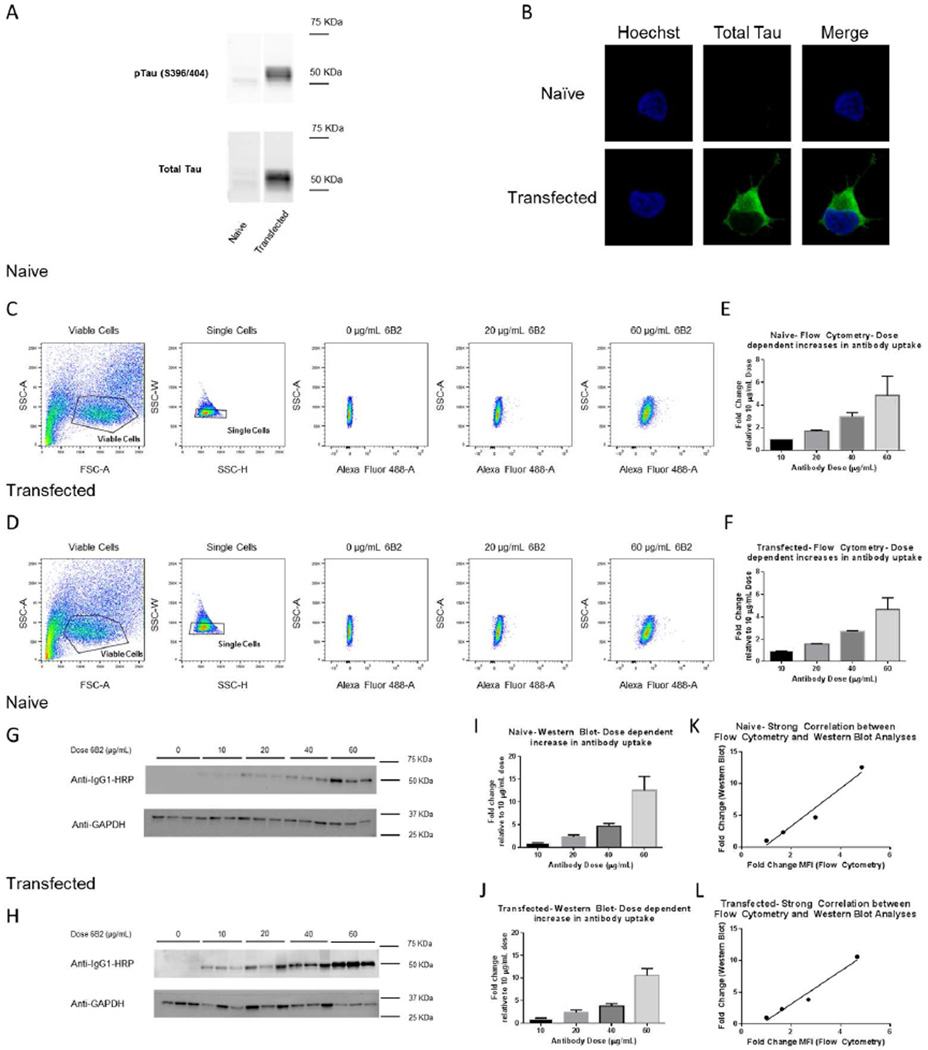

Initial characterization of the transfected SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing P301L mutant human tau revealed a robust overexpression compared to naïve SH-SY5Y cells, which for comparative purposes are underexposed (Figure 1A, B). Furthermore, naïve and transfected cells were incubated with increasing doses of monoclonal tau antibody, 6B2 (0–60 µg/mL) for 24 h. Tagged samples were analyzed using flow cytometry, which detected a dose-dependent increase in the Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence intensity (Figure 1C, D), and a dose-dependent increase in Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) for both cell lines (Figure 1E, F). Due to the specificity of our anti-mouse IgG1 HRP antibody, western blot analysis showed a single band for the heavy chain of the antibody (Figure 1G, H), and likewise, its quantification showed a dose-dependent increase in antibody uptake (Figure 1I, J). There was a strong positive correlation between the quantified flow cytometry and Western blot values in naïve and transfected cells (Figure 1K, L, r2=0.958, and r2=0.968, p=0.021 and p=0.016, respectively). In addition, we analyzed our flow cytometry samples for percent Alexa Fluor 488 positive cells (Figure 2A, B). In both naïve and transfected cells, percent positive cells increased dose-dependently and plateaued between the 40 and 60 ug/mL dosage (Figure 2C, D). From these dose-response curves, we chose 5 µg/mL, at the steepest part of the curves, as an ideal dosage for the dynamic experiments.

Figure 1. SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells dose-dependently take up tau monoclonal antibody, 6B2 as assessed by flow cytometry and Western blot analyses.

Non-transfected naïve SH-SY5Y cells and transfected SH-SY5Y cells expressing P301L tau were grown and maintained. Cells were either lysed for western blot or fixed with paraformaldehyde for confocal imaging. (A) Shows a comparison of western blot tau levels in naïve and P301L tau transfected SH-SY5Y cells. Transfected cells show a much greater degree of total (Dako) and phospho-tau (PHF-1) expression than the naïve cells. (B) Likewise, confocal imaging of these cells shows greater total tau expression (CP27) in transfected cells compared to naïve cells under the same fluorescence intensity. The naïve cells express tau, but the level of expression is much lower than in the transfected cells and hardly detectable under these conditions. Furthermore, naïve and transfected SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with different doses (0–60 µg/mL) of 6B2 tau antibody for 24 h. Cells were then collected and examined with flow cytometry or western blot analyses. (C and D) Scatter plots show how cells were gated for viable and singlet cells and further selected for Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence. (E and F) Quantification of median fluorescence intensities (MFI) of the Alexa Fluor 488 tagged 6B2 normalized to the 10 µg/mL dosage, which show a dose-dependent increase in antibody uptake/retention. (G and H) A representative Western blot probed with an anti-mouse IgG1 HRP-conjugated antibody to detect internalized antibody. (I and J) Western blot quantification, which shows a dose-dependent increase in antibody uptake normalized to the 10 µg/mL dosage. (K and L) Excellent correlation is observed between flow cytometry and Western blot analyses of tau antibody uptake for both naïve and transfected cells (r2=0.958, and r2=0.968, p=0.021, and p=0.016, n=3–8, and n=3–5, respectively). Graphs show mean values + standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 2. Dose dependent increase in antibody uptake and saturation.

Naïve and transfected SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0–60 µg/mL Alexa Fluor 488 tagged 6B2 tau antibody for 24 h. Cells were then collected and examined with flow cytometry. Cells were gated for viable and singlet cells and further selected for Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence. Samples were analyzed from previously described data sets in Figure 1 for percent Alexa Fluor 488 positive cells. (A and B) Show representative gating parameters after selecting for viable and single cells using a histogram to gate for percent positive cells in the 0 µg/mL 6B2 sample, which was then applied to the other doses. (C and D) Shows dose-dependent increase in percent positive cells for both cell lines, which plateaus between 40 and 60 µg/mL. Graphs show mean values + SEM.

Time of incubation and serum deprivation alter tau antibody uptake/retention as measured by flow cytometry

Naïve and transfected cells were treated with tagged 6B2 tau antibody for 24, 96, and 144 h in 10% or 1% FBS serum conditions to determine if prolonged incubation and/or enhanced stress associated with serum deprivation would alter antibody uptake. In both cell types, time-dependent increase in antibody uptake was observed, and was more pronounced in serum deprived media (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Antibody uptake/retention in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells is time-dependent and increases during serum deprivation.

Naïve and transfected SH-SY5Y, were treated with 5 µg/mL Alexa Fluor 488 tagged 6B2 tau antibody for 24 to 144 h at either 10% or 1% FBS serum levels. Cells were then collected and examined with flow cytometry, gated for viable and singlet cells, and further selected for Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence. Quantification of median fluorescence intensities (MFI) of the Alexa Fluor 488 tagged 6B2 was normalized to the negative control at each time point. Naive cells at 10% and 1% FBS showed a time-dependent increase in antibody uptake/retention between 24 and 144 h (###, ## 239%, 236%, p<0.001, p<0.01, n=3, respectively). Transfected cells showed a similar but more pronounced increase (####, ### 318%, 305%, p<0.0001, p<0.001, n=3, respectively). In addition, at 24, 96, and 144 h time points, the 1% FBS condition led to a greater antibody uptake/retention compared to 10% FBS condition, which trended mostly in naïve cells (n.s., ***, n.s.; 23%, 46%, 21%, p=0.20, p<0.001, p=0.08, n=3, respectively) and was consistently significant in transfected cells (*, **, *; 31%, 38%, 25%, p<0.05, p<0.01, p<0.05, n=3, respectively). n.s.: non-significant. Graphs show mean values + SEM.

A sub-population of neuroblastoma cells seeded with increasing doses of PHF and detected by flow cytometry shows a corresponding dose-dependent uptake of 6B2 tau antibody

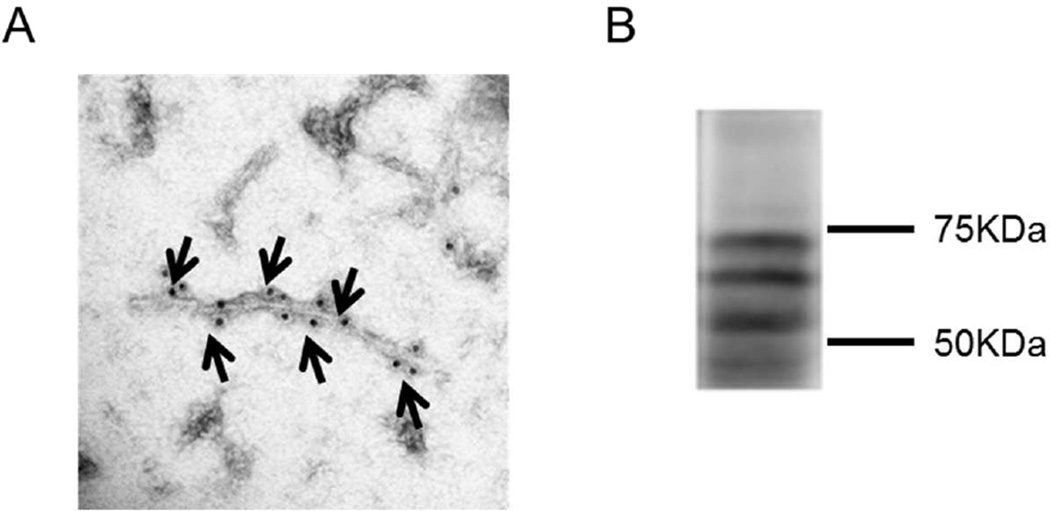

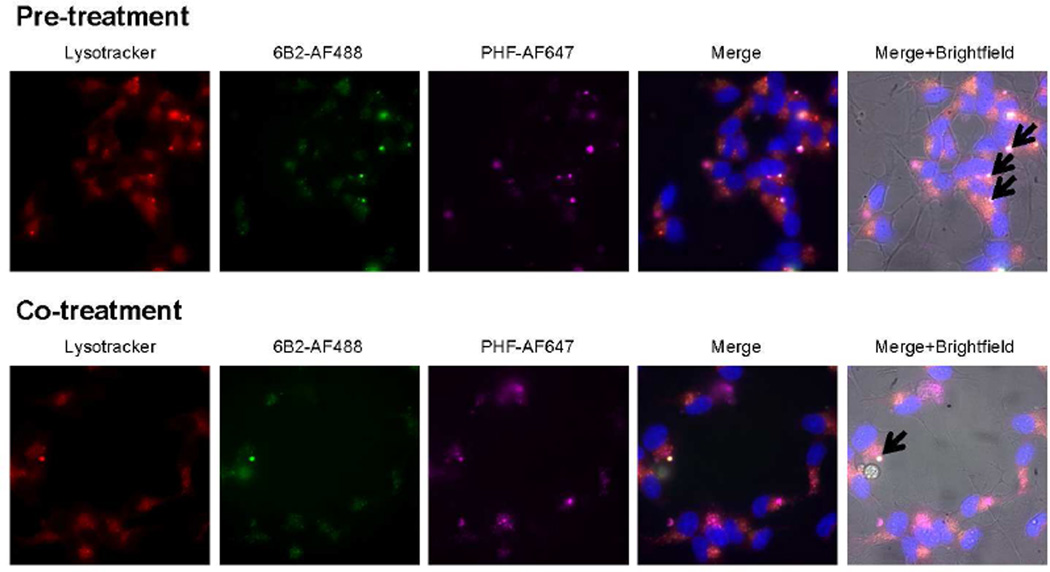

PHF tau was extracted and purified from the brain of a human AD patient. Purified PHF samples were characterized using electron microscopy and Western blot analyses (Figure 4). Transfected cells were pre-treated with increasing levels of tagged PHF for 24 h and then incubated with tagged 6B2 tau antibody for 24 h or co-treated with both reagents for 24 h. All samples were measured using flow cytometry. This paradigm revealed a sub-population of cells within the Q2 gating quadrant, which contains both PHF and tau antibody (Figure 5A). Quantification of the 6B2-AF488 percent positive cells in 6B2 controls samples (Q1 quadrant) compared to PHF and 6B2 treated cells (Q1+Q2 quadrants) showed a trend for a decrease in percent positive 6B2-AF488 cells as PHF load increased (Figure 5B). Further analyses of the Q2 quadrant region revealed that the MFI of both reagents increased with increasing PHF dose (Figure 5Ci, ii, iii, iv), and showed a strong correlation between PHF and antibody uptake levels (r2=0.999 and r2=0.999, p=0.011 and p=0.013, respectively, Figure 5Cv, vi). In further support of this finding, live imaging showed co-localization of PHF and tau antibody within the endosomal/lysosomal compartments under both conditions (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Characterization of PHF extracted from an Alzheimer’s brain.

PHF tau was extracted and purified from the brain of a human AD patient. Samples were analyzed using electron microscopy and western blot analysis. (A) Shows an immuno-electron microscopy image of PHF-1 tau positive fibril. Arrows indicate areas where antibody binding to fibril occurs. (B) Shows a corresponding Western blot of PHF tau sample probed with the CP27 antibody.

Figure 5. SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells treated with increasing doses of pathological PHF show a dose-dependent increase in tau antibody uptake, and these co-localize within a subpopulation of cells.

(A) Scatter plots of transfected SH-SY5Y cells expressing P301L either pre-treated with increasing levels of tagged PHF (0.1–10 µg/mL) for 24 h and then treated with tagged 6B2 tau antibody (5 µg/mL) for 24 h or co-treated with both for 24 h. Negative controls are untreated cells. The 6B2 control plot shows that within the Q1 quadrant, 7.2% and 3.5% of cells were positive in co-treated- and pre-treated cells, respectively. The plots show in the co- and pre-treated PHF+ 6B2 samples a sub-population in the Q2 quadrant gate, which contains both tau antibody and PHF, which is 1.7 to 5.5% of the total cell population (2.2% to 5.5% in co-treated cells and 1.7% to 3.0% in pre-treated cells). (B) Quantification of percent 6B2-AF488 positive cells from Q1 and Q2 quadrant data in co- and pre-treated cells. As PHF load increases, the percent of positive cells trended towards a decrease. (C) MFI (Alexa Fluor 488 and 647) of all PHF+6B2 samples were analyzed from the Q2 quadrants and normalized to the Q2 MFI’s of the 0.1 µg/mL PHF+6B2 sample. Quantification shows a dose-dependent increase in antibody and PHF signal in pre- and co--treated samples. Under both conditions, uptake/retention of tau antibody and PHF strongly correlate (r2=0.999 and r2=0.999, p=0.011 and p=0.013, n=3, respectively).

Figure 6. Tau antibody co-localizes with pathological PHF tau in the endosomal/lysosomal compartments.

Representative live images of cells under the pre- and co-treatment conditions depicted in Figure 5, using 1 µg/mL tagged-PHF and 5 µg/mL tagged-6B2 antibody. Black arrows in the Merge+Brightfield panel point at foci with intense triple co-localization of Lysotracker, 6B2 tau antibody, and PHF.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have successfully demonstrated that flow cytometry is a convenient method to detect and quantify tau antibodies that are internalized into naïve, and transfected SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. We chose this stable cell line because of SH-SY5Y cells’ ability to handle the flow cytometry process under live conditions [36,37]. In addition, we chose to transfect SH-SY5Y with the P301L mutation as this mutation is commonly used for tauopathy studies. Our flow cytometry technique showed a strong positive correlation with Western blot analysis, which has previously been used in our laboratory for this purpose in primary neuronal mouse cultures [13], and are more difficult to study with flow cytometry.

We also demonstrated our ability to detect intracellular PHF material in transfected cells with flow cytometry, and how its uptake influences tau antibody uptake/retention. Measuring cells’ capacity to internalize various tau fractions and recombinant tau to monitor the uptake and spread of tau pathology has been reported using more conventional techniques [11,16,38–40], as well as with flow cytometry [29,30,41–43]. However, such measurements have not been previously combined with analysis of tau antibody uptake. Hence, we have gone a step further in our flow cytometry studies, in which we multiplexed both the antibody and tau uptake signals to monitor both at the same time and how they relate.

The degree of tau antibody uptake/retention as detected by flow cytometry depended on antibody dosage, incubation period, and the environmental conditions. As expected, the MFI and percentage of positive cells increased with higher antibody doses. From this data we created a dose response curve to select an ideal antibody dosage for treating the cells, which would allow us to detect changes in uptake under varying conditions. Serum deprivation led to an increase in antibody uptake which may be due to enhanced endocytosis under stress conditions. Likewise, as predicted, longer incubation period increased antibody uptake in naïve cells, and to a greater extent in transfected cells. This manipulation was further exemplified in our pre- and co-treatment of PHF and 6B2 tau antibody in transfected cells for 24 h, which revealed a subpopulation of cells that contained both reagents. These pre- and co-treatment experiments showed a strong correlation between the amount of PHF and tau antibody uptake, in agreement with previous studies in our laboratory, which have indicated that tau antibody uptake correlates with tau pathology load [13,14].

The sub-population of transfected cells that contain both antibody and PHF positive cells was between 1.7 to 5.5% of the total cell population. The percentage of 6B2-AF488 positive cells showed a non-significant trend for a decrease as PHF dosage increased mainly in co-treated cells and only at the highest PHF dosage in pre-treated cells. This trend may be attributed to some of the antibody being sequestered by PHF in the extracellular space, and, therefore, not being able to access the cell for uptake. Another possibility is that some of the cells may have died due to PHF toxicity.

The PHF fraction alone is most likely internalized by bulk-mediated endocytosis [39,43], while the antibody with or without PHF appears to be internalized through Fc-receptor and bulk-mediated processes [13,28]. Since the neuroblastoma cells are non-differentiated and only neuronal-like, these mechanisms may not fully apply as we have seen previously in actual neurons. In non-differentiated neuroblastoma, the primary vehicle of uptake may be bulk-mediated endocytosis, which is a relatively non-specific process. This phenomenon may explain antibody detection in naïve cells, which is much more limited in wild-type brain slice cultures [13,14]. The extent of antibody uptake in the undifferentiated naïve cells is analogous to Fab uptake in wild-type brain slice culture, which is considerable and occurs via bulk-mediated endocytosis [14]. However, based on our live imaging findings, downstream events are likely similar in different model systems, with tau antibodies entering the endosomal-lysosomal system and co-localizing with pathological tau material, as we and others have seen in primary and brain slice cultures as well as in vivo [4,13,14,21,34]. We are in the process of comparing uptake and efficacy of various tau antibodies in non-differentiated-, as used here, and in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, which are closer to actual neurons [44].

Overall, this study shows the potential of this multiplexing approach to detect antibody and tau internalization into cells in the same culture assay, and will be an asset to rapidly screen and quantify such events. It can then complement conventional techniques to better understand the mechanism of action of tau antibodies and the uptake and spread of pathological tau proteins.

Research in Context.

Systematic review

Prior literature was reviewed through traditional sources, such as PubMed. Several articles have reported on internalization of tau protein or its antibodies but not in the same study. Furthermore, we are not aware of another approach that can quickly measure and quantify such interaction.

Interpretation

This flow cytometry approach can simultaneously track and multiplex the signals of the internalization of tau protein and its antibodies in cells. It allows quick assessment of antibody uptake and retention in conjunction with pathological tau protein prior to longer studies in animals or other more complex models.

Future directions

To use this high-throughput approach to determine if/how the extent of such internalization and association within the same cells translate into clearance of pathological tau protein. Also, to determine if antibody efficacy in undifferentiated cells corresponds to such effects in differentiated cells.

Acknowledgments

EMS is supported by NIH R01 grants NS077239, AG032611 and AG020197 and in part by R24OD18340 and R24OD018339. He is an inventor on patents on tau immunotherapy and related diagnostics that are assigned to New York University. This technology is licensed to and is being co-developed with H. Lundbeck A/S.

DBS was also supported in part with NIH training grants NS 69514-1 and MH 96331-2.

We would like to thank Michael Gregory and Professor Peter Lopez of the NYU School of Medicine Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core (support grant P30CA016087) for flow cytometry advice and training, and Dr. Yan Deng of the NYU School of Medicine Microscopy Core for help with live imaging. Both facilities are supported in part by grant UL1 TR00038 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health.

Peter Davies at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, generously provided PHF1 and CP27 tau antibodies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pedersen JT, Sigurdsson EM. Tau immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spencer B, Masliah E. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: past, present and future. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:114. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu YJ, Watts RJ. Developing therapeutic antibodies for neurodegenerative disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2013;10:459–472. doi: 10.1007/s13311-013-0187-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau conformers in a tangle mouse model reduces brain pathology with associated functional improvements. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9115–9129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2361-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutajangout A, Ingadottir J, Davies P, Sigurdsson EM. Passive immunization targeting pathological phospho-tau protein in a mouse model reduces functional decline and clears tau aggregates from the brain. J Neurochem. 2011;118:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau prevents cognitive decline in a new tangle mouse model. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16559–16566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boimel M, Grigoriadis N, Lourbopoulos A, Haber E, Abramsky O, Rosenmann H. Efficacy and safety of immunization with phosphorylated tau against neurofibrillary tangles in mice. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:472–485. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai X, Wu S, Murray TK, Kinley R, Cella CV, Sims H, Buckner N, Hanmer J, Davies P, O'Neill MJ, Hutton ML, Citron M. Passive immunization with anti-Tau antibodies in two transgenic models: reduction of Tau pathology and delay of disease progression. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34457–34467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bi M, Ittner A, Ke YD, Gotz J, Ittner LM. Tau-Targeted Immunization Impedes Progression of Neurofibrillary Histopathology in Aged P301L Tau Transgenic Mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Troquier L, Caillierez M, Burnouf S, Fernandez-Gomez FJ, Grosjean MJ, Zommer N, Sergeant N, Schraen-Maschke S, Blum D, Buee L. Targeting phospho-Ser422 by active Tau immunotherapy in the THY-Tau22 mouse model: a suitable therapeutic approach. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:397–405. doi: 10.2174/156720512800492503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kfoury N, Holmes BB, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI. Trans-cellular Propagation of Tau Aggregation by Fibrillar Species. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19440–19451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.d'Abramo C, Acker CM, Jimenez HT, Davies P. Tau Passive Immunotherapy in Mutant P301L Mice: Antibody Affinity versus Specificity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Congdon EE, Gu J, Sait HB, Sigurdsson EM. Antibody Uptake into Neurons Occurs Primarily via Clathrin-dependent Fcgamma Receptor Endocytosis and Is a Prerequisite for Acute Tau Protein Clearance. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35452–35465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.491001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu J, Congdon EE, Sigurdsson EM. Two novel Tau antibodies targeting the 396/404 region are primarily taken up by neurons and reduce Tau protein pathology. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33081–33095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.494922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theunis C, Crespo-Biel N, Gafner V, Pihlgren M, Lopez-Deber MP, Reis P, Hickman DT, Adolfsson O, Chuard N, Ndao DM, Borghgraef P, Devijver H, van LF, Pfeifer A, Muhs A. Efficacy and safety of a liposome-based vaccine against protein Tau, assessed in tau.P301L mice that model tauopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanamandra K, Kfoury N, Jiang H, Mahan TE, Ma S, Maloney SE, Wozniak DF, Diamond MI, Holtzman DM. Anti-tau antibodies that block tau aggregate seeding in vitro markedly decrease pathology and improve cognition in vivo. Neuron. 2013;80:402–414. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo-Carranza DL, Gerson JE, Sengupta U, Guerrero-Munoz MJ, Lasagna-Reeves CA, Kayed R. Specific targeting of tau oligomers in htau mice prevents cognitive impairment and tau toxicity following injection with brain-derived tau oligomeric seeds. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:S97–S111. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Guerrero-Munoz MJ, Lasagna-Reeves CA, Gerson JE, Singh G, Estes DM, Barrett AD, Dineley KT, Jackson GR, Kayed R. Passive Immunization with Tau Oligomer Monoclonal Antibody Reverses Tauopathy Phenotypes without Affecting Hyperphosphorylated Neurofibrillary Tangles. J Neurosci. 2014;34:4260–4272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3192-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walls KC, Ager RR, Vasilevko V, Cheng D, Medeiros R, LaFerla FM. p-Tau immunotherapy reduces soluble and insoluble tau in aged 3xTg-AD mice. Neurosci Lett. 2014;575:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontsekova E, Zilka N, Kovacech B, Novak P, Novak M. First-in-man tau vaccine targeting structural determinants essential for pathological tau-tau interaction reduces tau oligomerisation and neurofibrillary degeneration in an Alzheimer's disease model. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:44. doi: 10.1186/alzrt278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collin L, Bohrmann B, Gopfert U, Oroszlan-Szovik K, Ozmen L, Gruninger F. Neuronal uptake of tau/pS422 antibody and reduced progression of tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2014;137:2834–2846. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selenica ML, Davtyan H, Housley SB, Blair LJ, Gillies A, Nordhues BA, Zhang B, Liu J, Gestwicki JE, Lee DC, Gordon MN, Morgan D, Dickey CA. Epitope analysis following active immunization with tau proteins reveals immunogens implicated in tau pathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:152. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ittner A, Bertz J, Suh LS, Stevens CH, Gotz J, Ittner LM. Tau-targeting passive immunization modulates aspects of pathology in tau transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2015;132:135–145. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umeda T, Eguchi H, Kunori Y, Matsumoto Y, Taniguchi T, Mori H, Tomiyama T. Passive immunotherapy of tauopathy targeting pSer413-tau: a pilot study in mice. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2:241–255. doi: 10.1002/acn3.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.d'Abramo C, Acker CM, Jimenez H, Davies P. Passive Immunization in JNPL3 Transgenic Mice Using an Array of Phospho-Tau Specific Antibodies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bright J, Hussain S, Dang V, Wright S, Cooper B, Byun T, Ramos C, Singh A, Parry G, Stagliano N, Griswold-Prenner I. Human secreted tau increases amyloid-beta production. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:693–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sankaranarayanan S, Barten DM, Vana L, Devidze N, Yang L, Cadelina G, Hoque N, DeCarr L, Keenan S, Lin A, Cao Y, Snyder B, Zhang B, Nitla M, Hirschfeld G, Barrezueta N, Polson C, Wes P, Rangan VS, Cacace A, Albright CF, Meredith J, Jr, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Brunden KR, Ahlijanian M. Passive immunization with phospho-tau antibodies reduces tau pathology and functional deficits in two distinct mouse tauopathy models. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo A, Shahpasand K, Mannix R, Qiu J, Moncaster J, Chen CH, Yao Y, Lin YM, Driver JA, Sun Y, Wei S, Luo ML, Albayram O, Huang P, Rotenberg A, Ryo A, Goldstein LE, Pascual-Leone A, McKee AC, Meehan W, Zhou XZ, Lu KP. Antibody against early driver of neurodegeneration cis P-tau blocks brain injury and tauopathy. Nature. 2015;523:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature14658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanamandra K, Jiang H, Mahan TE, Maloney SE, Wozniak DF, Diamond MI, Holtzman DM. Anti-tau antibody reduces insoluble tau and decreases brain atrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2:278–288. doi: 10.1002/acn3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funk KE, Mirbaha H, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI. Distinct Therapeutic Mechanisms of Tau Antibodies: Promoting Microglial Clearance Versus Blocking Neuronal Uptake. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:21652–21662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.657924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder SK, Joly-Amado A, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Tau-Directed Immunotherapy: A Promising Strategy for Treating Alzheimer's Disease and Other Tauopathies. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11481-015-9637-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castillo-Carranza DL, Guerrero-Munoz MJ, Sengupta U, Hernandez C, Barrett AD, Dineley K, Kayed R. Tau immunotherapy modulates both pathological tau and upstream amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. J Neurosci. 2015;35:4857–4868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4989-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai CL, Chen X, Kazim SF, Liu F, Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Passive immunization targeting the N-terminal projection domain of tau decreases tau pathology and improves cognition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease and tauopathies. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2015;122:607–617. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1315-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnamurthy PK, Deng Y, Sigurdsson EM. Mechanistic Studies of Antibody-Mediated Clearance of Tau Aggregates Using an ex vivo Brain Slice Model. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:59. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnaswamy S, Lin Y, Rajamohamedsait WJ, Rajamohamedsait HB, Krishnamurthy PK, Sigurdsson EM. Antibody derived in vivo imaging of tau pathology. 2014 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-14.2014. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamir DB, Rosenqvist N, Rasool S, Pedersen JT, Sigurdsson EM. Uptake of tau antibodies into PHF-pretreated transfected human neuroblastoma cells leads to a decrease in tau protein levels. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2014;10:P647. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamir DB, Rosenqvist N, Gregory MD, Rasool S, Pedersen JT, Sigurdsson EM. Uptake of tau antibodies and paired helical filament enriched tau protein in naive and transfected human neuroblastoma cells. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2013 524.05/H21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC, Belaygorod L, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI. Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4376–E4385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411649111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santa-Maria I, Varghese M, Ksiezak-Reding H, Dzhun A, Wang J, Pasinetti GM. Paired helical filaments from Alzheimer disease brain induce intracellular accumulation of Tau protein in aggresomes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20522–20533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker LC, Diamond MI, Duff KE, Hyman BT. Mechanisms of protein seeding in neurodegenerative diseases. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:304–310. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI. Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12845–12852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Falcon B, Cavallini A, Angers R, Glover S, Murray TK, Barnham L, Jackson S, O'Neill MJ, Isaacs AM, Hutton ML, Szekeres PG, Goedert M, Bose S. Conformation determines the seeding potencies of native and recombinant Tau aggregates. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:1049–1065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.589309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu JW, Herman M, Liu L, Simoes S, Acker CM, Figueroa H, Steinberg JI, Margittai M, Kayed R, Zurzolo C, Di PG, Duff KE. Small misfolded Tau species are internalized via bulk endocytosis and anterogradely and retrogradely transported in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1856–1870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shamir DB, Sigurdsson EM. Tau antibodies reduce tau levels in differentiated but not in non-differentiated human SH-SY5Y cells. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2015 579.15/C45. [Google Scholar]