Abstract

High consanguinity rates, poor access to accurate diagnostic tests, and costly therapies are the main causes of increased burden of lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) in developing countries. Therefore, there is a major unmet need for accurate and economical diagnostic tests to facilitate diagnosis and consideration of therapies before irreversible complications occur. In cross-country study, we utilized dried blood spots (DBS) of 1,033 patients clinically suspected to harbor LSDs for enzymatic diagnosis using modified fluorometric assays from March 2013 through May 2015. Results were validated by demonstrating reproducibility, testing in different sample types (leukocytes/plasma/skin fibroblast), mutation study, or measuring specific biomarkers. Thirty percent (307/1,033) were confirmed to have one of the LSDs tested. Reference intervals established unambiguously identified affected patients. Correlation of DBS results with other biological samples (n = 172) and mutation studies (n = 74) demonstrated 100% concordance in Gaucher, Fabry, Tay Sachs, Sandhoff, Niemann-Pick, GM1, Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), Fucosidosis, Mannosidosis, Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) II, IIIb, IVa, VI, VII, and I-Cell diseases, and 91.4% and 88% concordance in Pompe and MPS-I, respectively. Gaucher and Pompe are the most common LSDs in India and Pakistan, followed by MPS-I in both India and Sri Lanka. Study demonstrates utility of DBS for reliable diagnosis of LSDs. Diagnostic accuracy (97.6%) confirms veracity of enzyme assays. Adoption of DBS will overcome significant hurdles in blood sample transportation from remote regions. DBS enzymatic and molecular diagnosis should become the standard of care for LSDs to make timely diagnosis, develop personalized treatment/monitoring plan, and facilitate genetic counseling.

Keywords: Diagnostic accuracy, Dried blood spots, Enzymatic diagnosis, Lysosomal enzymes, Lysosomal storage disorders, Molecular diagnosis

Introduction

Enzyme assays have been the gold standard for providing definitive diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) by demonstrating deficient enzyme activity in leukocytes/plasma/cultured fibroblast. This can be further confirmed by mutation studies. Interference by isoenzymes in leukocytes and pseudo deficiency states in plasma can lead to misdiagnosis (Burin et al. 2000; Filocamo and Morrone 2011), whereas fibroblasts require an invasive skin biopsy and a long waiting period for the culture to obtain an adequate number of cells for testing (Coelho and Guigliani 2000). To overcome these limitations, enzyme estimation on dried blood spots (DBS) has been introduced in recent years (Civallero et al. 2006; Ceci et al. 2011). Although initiated for purpose of screening in newborns (Chamoles et al. 2001), DBS technique has now been adopted for early diagnosis of LSDs due to the requirement of a few drops of blood, easy transportation especially from remote areas and simultaneous measurement of multiple analytes without special storage requirements (Muller et al. 2010). Specific therapeutic intervention is available for MPS (I, II, IVa, and VI), Fabry, Pompe, and Gaucher, however, accurate and timely diagnosis is crucial for maximizing the benefit (Camelier et al. 2011; Kaminsky and Lidove 2014).

The burden of LSDs in India is severe because of large population, high consanguinity rate, lack of awareness and expertise, and limited genetic testing centers for providing correct diagnosis (Verma et al. 2012; Mistri et al. 2014; Sheth et al. 2014). Therefore, the present study was planned to develop evidence-based simple, reliable, and validated DBS methods to produce reproducible and accurate biochemical diagnosis for LSDs.

The previously established DBS enzymatic methods for the diagnoses of LSDs were modified to simplify assay procedures without compromising quality. Patients were diagnosed enzymatically for 18 different LSDs after validation. Diagnostic efficacy was proven by correlating results of DBS with those obtained from other biological samples/biomarkers/mutation studies. Additionally, testing accuracy was also ensured by participating in a pilot proficiency testing program (www.erndimqa.nl).

Materials and Methods

A DBS kit [customized card (Whatman 903) for blood sampling, lancet, and desiccant] with envelope was provided by Genzyme (India), a Sanofi company to clinicians in India and neighboring countries (Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh) for lysosomal enzyme testing in suspected cases of LSDs at our genetic center under “India Compassionate Access program.” Dried blood specimens (n = 1,033) were received with brief clinical details, from March 2013 through May 2015. The mean age of patients (51% male) was 3 years (range 1 day to 65 years). For validation, blood samples of patients and normal subjects were collected in heparin tubes and on filter paper for leukocytes and DBS assays, respectively, where feasible. Plasma was separated from blood and stored at −80°C until use. For assays in skin fibroblast (SF), skin was biopsied from patients for culture followed by enzyme testing.

DBS protocols used to estimate various enzyme activities were modified with changes in elution buffer, molarities, pH of substrate buffers, and stopping solutions as given in Table 1 with references (a–n). Enzymes included were: β-glucosidase (EC:3.2.1.21), chitotriosidase (EC:3.2.1.14), sphingomyelinase (EC:3.1.4.12), β-galactosidase (EC:3.2.1.23), β-hexosaminidase A (EC:3.2.1.52), total hexosaminidase (EC:3.2.1.52), α-glucosidase (EC:3.2.1.20), α-galactosidase (EC:3.2.1.22), palmitoyl protein thioesterase (EC:3.1.2.22), tripeptidyl peptidase (EC:3.4.14.9), α-fucosidase (EC:3.2.1.51), α-mannosidase (EC:3.2.1.24), α-iduronidase (EC:3.2.1.76), iduronate 2 sulfatase (EC:3.1.6.13), α-N-acetylglucosaminidase (EC:3.2.1.50), galactose 6 sulfatase (EC:2.5.1.5), aryl sulfatase B (EC:3.1.6.12), and β-glucuronidase (EC:3.2.1.31).

Table 1.

Modified protocols for the estimation of 18 lysosomal enzymes on dried blood spots with biological reference intervals

| Enzymes | Procedure (DBS dried blood spot, EL elution buffer, SB substrate buffer, SU substrate, ST stopping buffer) | Biological reference interval | % Enzyme activity in affected = affected mean/normal mean | Referencesa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (nmol/h/ml) | Patients (nmol/h/ml) | ||||

| βGLU | DBS + 50 μL SB: 0.4 M CP, pH: 5.5 + SU: 100 μL 5 mM MβGLU containing 0.2% NaTC in 0.2 M SAB, pH 5.5 + 5 h at 37°C+ ST: 1,350 μL EDA | (n = 139): 2.3–18.4, mean = 5.0 | (n = 35): 0.062–2.0, mean: 0.8 | 16.0 | a, c |

| CHT | DBS+ EL: 40 μL 0.1 M SAB, pH 5.2+ SU: 40 μL 22 mM TAC in 0.1 M/0.2 M CP, pH 5.2+ 30 min at 37°C + 600 μL EDA | (n = 70): 0.062–100, mean = 23.2 | (n = 35): 100–554.0, mean: 254.7 | – | a, d |

| ASM | DBS+ EL: 60 μL D/W + 20 μL NaTC (0.2%) + 20 μL 0.1 M SAB, pH 5.2 + SU : 20 μL 0.68 mM HMP in 0.1 M SAB, pH 5.2 + 20 h at 37°C + ST: 380 μL AMP | (n = 20): 1.94–23.9, mean: 8.3 | (n = 5): 0.062–0.8, mean: 0.4 | 4.8 | c, e |

| βGal | DBS + 50 μL D/W+ SU: 50 μL 1 mM MβGal in 0.1/0.2 M CP, pH: 4.0 + 0.1 M sodium chloride + 3 h at 37°C + ST: 500 μL AMP | (n = 45): 20.7–69.0, mean: 32.8 | (n = 7): 0.062–3.0, mean: 2.1 | 6.4 | a, f |

| βHex A | DBS +EL: 50 μL D/W, SU: 30 μL 1 mM MβACGlu in 0.1/0.2 M CP, pH 4.4, + 3 h at 37°C + ST: 420 μL AMP | (n = 22) :26.9–186.5, mean: 85.5 | (n = 7): 0.062–3.64, mean: 1.8 | 2.1 | a, g |

| (n = 3): >100.0 (I-cell) | |||||

| Total hex | DBS+ EL: 50 μL 0.2 M/0.4 M CP, pH: 4.5 + SU: 100 μL 3 mM MACDGlu + 2 h at 37°C + ST: 300 μL EDA | (n = 20) :24.0–191.6, mean: 78.6 | (n = 5): 0.062–3.5, mean: 2.5 | 3.2 | a, g |

| αGlu | Total acid αGlu (assay without acarbose inhibitor): DBS + 50 μL D/W | (n = 52): Total acid αGlu: 15.5–92.2; lysosomal acid αGlu: 5.5–29.6 | (n = 15): Total acid αGlu: 4.8–38.3; lysosomal acid αGlu: 0.86–5.5, | 25.0 (% ratio) | h |

| Lysosomal acid αGlu (assay with acarbose (7.5 μM) inhibitor): DBS+ 10 μL D/W + 40 μL acarbose | Ratiob: 0.25–0.75, mean: 0.44 | Ratiob: <0.22, mean: 0.11 | |||

| Both sets kept for 2 h at RT + SU: 50 μL 4 mM MαGlu in 0.1/0.2 M CP, pH 4.0 in all tubes + O/N at 37°C + ST: 300 μL EDA | Poor controlc (n = 15): total acid αGlu: 0.96–16.5, lysosomal acid αGlu: 0.29–6.7 | ||||

| Ratio: 0.27–0.8b | |||||

| αGal | DBS+ SU: 70 μL 5 mM MαGal in 0.1/0.2 M CP, pH 4.5 + O/N at 37°C + ST: 300 μL EDA | (n = 18):2.57–7.8, mean: 5.5 | (n = 3): 0.062–1.0, mean: 0.4 | 7.2 | a, b |

| PPT | DBS + EL: 100 μL D/W + 30 min. at 37°C. Take 10 μL + SU: 20 μL 0.64 mM MPβGlc + 48 h at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 15): 5.0–12.5, mean: 8.2 | (n = 5): 0.062–2.6, mean: 1.8 | 21.9 | i |

| TPP | DBS + EL: 100 μL D/W + 30 min. at 37°C. Take 10 μL + SU: 100 μL 500 μM AAPAMC in 0.1 M SAB, pH 4.0 + 40 μL NaCl + 48 h at 37°C + 200 μL AMP | (n = 15): 30–80, mean = 51.2 | (n = 2): 0.062–5.0, mean: 3.4 | 6.6 | j |

| αFuco | DBS + EL: 40 μL D/W + SU: 40 μL 0.75 mM MαF in 0.1/0.2 MCP, pH 5.8 + 3 h at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 15):20–65.0, mean: 38.9 | (n = 3): 0.062–3.0, mean: 2.2 | 5.6 | f |

| αManno | DBS + EL: 40 μL D/W + SU: 40 μL 5 mM MαM in 0.1/0.2 MCP, pH: 5.8 + 3 h at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 15): 22–67.0, mean: 43.6 | – | f | |

| αIdu | DBS + EL: 30 μL D/W + 10 μL formate buffer, pH: 3.5 + 20 μL SL + SU: 20 μL 2 mM MαIdu in formate buffer, pH: 3.5 + O/N at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 50): 2.4–12.0, mean: 4.5 | (n = 12): 0.062–0.5, mean: 0.23 | 5.1 | k |

| (n = 5):>25.0 (I-cell) | |||||

| Idu2s | DBS+ EL: 100 μL D/W+ 30 min. at 37°C. Take 10 μL + SU: 20 μL MαIdu2S in 0.1 M SAB, pH 5.0 containing 10 mM lead acetate + 24 h at 37°C+ 40 μL 0.2M/0.4M CP + 10 μL LEBT+ 24 h at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 18): : 11–35, mean: 17.5 | (n = 5): 0.062–9.0, mean: 4.2 | 24.0 | l |

| αHex | DBS + EL: 100 μL D/W + 37°C for 30 min. Take 10 μL supernatant + SU: 20 μL 0.25 mM MαNACGLU + O/N at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 12): 2.4–3.8, mean: 2.8 | (n = 2): 0.062–0.16, mean: 0.1 | 3.6 | m |

| G6S | DBS+ SU: 20 μL 10 mM MG6STEA in 0.1 M SAB, pH 4.3+ 48 h at 37°C+ 5 μL 0.9 M phosphate buffer, pH 4.3+ 10 μL β-galactosidase + 6 h at 37°C + ST: 200 μL AMP | (n = 15): 7.5–43.5, mean: 15.4 | (n = 7): 0.062–1.5, mean: 0.8 | 5.2 | n |

| ASB | DBS + EL: 50 μL D/W + SU: 75 μL 10 mM MS in 0.2 MSAB, pH: 6.0 with 5 mM barium acetate + O/N at 37°C + ST: 450 μL AMP | (n = 15): 5.2–50.0, mean : 22.1 | (n = 5): 0.062–1.2, mean: 0.9 | 4.0 | f |

| βGlur | DBS+ SU : 50 μL of 5 mM MβGlr in 0.1 MSAB, pH: 4.0 + ST: 300 μL EDA | (n = 12): 5.5–45.8, mean: 23.8 | (n = 5): 0.062–2.5, mean : 1.1 | 4.6 | f |

| (n = 5): >200.0 (I-cell) | |||||

Enzymes: βGLU β-glucosidase, CHT chitotriosidase, ASM acid sphingomyelinase, βGal β-galactosidase, βHex A β-hexosaminidase A, Total hex total hexosaminidase, αGlu α-glucosidase, αGal α-galactosidase, PPT palmitoyl-protein thioesterase, TPP tripeptidyl peptidase, α-Fuco α-fucosidase, α-Manno α-mannosidase, αIdu α-iduronidase, Idu2s iduronate 2-sulfatase, αHex α-hexosaminidase, G6S galactose 6 sulfatase, ASB aryl sulfatase B, βGlur β glucuronidase

Reagents: CP citrate –phosphate buffer, EDA 0.3 M ethylene diamine, SAB sodium acetate buffer-adjust pH with 0.01 M acetic acid, TAC 4Mu β NNN tri-acetyl chitotriosidase, Mβ-GLU 4MU β-glucoside, D/W distilled water, NaTC sodium taurocholate, HMP 6-hexadecanoylamino 4-methylumbelliferyl –phosphorylcholine, AMP 0.1 M 2-amino, 2-methyl, 1-propanol, pH 10.3, Mβ Gal 4 Mu β-d-galactopyranoside, MβACGlu 4 Mu β-N—Ac-glucosaminide 6 sulfate, MACDGlu 3 mM 4 MU 2-acetamido 2-deoxy β-d glucopyranoside, MαGlu 4Mu α-d-glucopyranoside, O/N overnight (17 h), MαGal 4Mu α-d-galactopyranoside with 125 mM N-acetyl d-galactosamine, MPβGlc 4 MU -6S-palm-β-Glc, AAPAMC AAP-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin, MαF 4Mu α-l-fucoside, MαM 4Mu α-d mannopyranoside, SL saccharolactone, MαIdu 4 Mu α-l-iduronide (glycosynth), MαIdu2S 4- MU α-l iduronide 2 sulfate, LEBT lysosomal enzymes from bovine testis, MαNACGLU: 4-methylumbelliferyl α-N-acetyl glucosaminide, MG6STEA 4Mu-β-galactoside 6-sulfate.triethyl ammonium, MS 4Mu sulfate, MβGlr 4 Mu β-glucuronide

Blank: One blank tube was always set for each sample in the assay in which all reagents were added and kept under identical conditions except substrate. Substrate was incubated under identical conditions in separate tube without DBS specimen. This substrate was added in the blank tube immediately after stopping before taking reading

Analytical sensitivity: Since analytical sensitivity of these fluorometric enzyme assays is 0.062 nmol/h/mL, the affected range is given from 0.062 (Verma et al. 2015)

Multiple sulfatase deficiency (MSD): MSD patients can be diagnosed by determining deficiency of iduronate 2 sulfatase, galactose 6 sulfatase, and aryl sulfatase B enzymes

a References: a: Civallero et al. (2006); b: Chamoles et al. (2001); c: Chamoles et al. (2002a); d: Hollak et al. (1994); e: van Diggelen et al. (2005); f: Kelly (1977); g: Chamoles et al. (2002b); h: Winchester et al. (2008); i: van Diggelen et al. (1999); j: Lukacs et al. (2003); k: Hopwood et al. (1979); l: Voznyi et al. (2001); m: Marsh and Fensom (1985), and n: Camelier et al. (2011)

bRatio = lysosomal acid αGlu/total acid αGlu

cNormal cases with low levels of both total acid α-glucosidase and lysosomal acid α-glucosidase while ratio within normal range

One positive (affected case) and one negative (normal subject) controls were run with each assay. After incubation and stopping reactions as per modified protocols, fluorescence (excitation 365 nm, emission 455 nm) was read using Victor 2D multi-label counter (Perkin Elmer). Fluorescence readings were corrected for blanks (substrate incubated separately without DBS under identical conditions was added in blank tube immediately after stopping solution). A standard curve of 4 methylumbelliferone was used to extrapolate fluorescence count to moles of enzymatic product, and enzyme activity was calculated in nmol/h/mL of blood or nmol/h/mg of protein. Temperature effect on enzyme activity during transportation of DBS specimens from distant places was taken into account to rule out false positives by simultaneously testing either β-glucuronidase or β-galactosidase as a reference control enzyme in the same sample to verify sample integrity. In cases where the reference enzyme was deficient as well, repeat sample was requested.

To validate DBS methods for 18 lysosomal enzymes, reproducibility was demonstrated by intra- (n = 3) and inter-assay (n = 10) results using threshold of %CV <15 (Verma et al. 2015). DBS results of affected and normal cases (n = 172) were correlated by performing simultaneous assays in leukocytes/plasma/cultured SF samples. Since the transportation of liquid blood samples across the international borders/distant places was a big hurdle, DBS results of another 74 cases were confirmed by molecular studies. DNA was extracted from DBS (used previously for enzymatic analysis) and analyzed by PCR sequencing of all coding exons and flanking intronic regions (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, USA and ARCHIMED Life Science GmbH, Vienna, Austria; www.archimedlife.com). Bio-informatic interpretation was done to predict severity of mutations. These 246 cases including patients of 18 different LSDs (either confirmed by mutation or testing in other biological materials) were used to evaluate diagnostic efficacy of DBS enzyme assays. Results were also correlated with abnormal biomarkers including chitotriosidase (CHT) activity in Gaucher disease, creatine phosphokinase (CK) in Pompe, and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses. To ensure testing quality and specificity, the laboratory participated in a pilot study of lysosomal enzymes testing on DBS run by ERNDIM, The Netherlands, and performance was evaluated. These validated DBS methods were further used to identify the patients of different LSDs.

Results

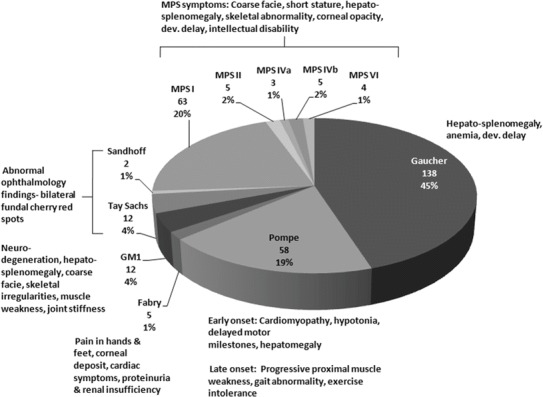

Of 1,033 cases, 307 were found to have enzyme deficiency for one of the LSDs tested (Fig. 1). The reference intervals established for patients and normal subjects (Table 1) were used to analyze these patients. The largest cohort of 138 cases was diagnosed for Gaucher, followed by Hurler (n = 63), Pompe (n = 58), Tay Sachs (n = 12), and GM1 gangliosidosis (n = 12). Among these, 209 patients were from India (Gaucher: 80, Pompe: 52, MPS-I: 30, Fabry: 4, MPS (II, IV, VI): 17, Tay Sachs/Sandhoff: 14, and GM1: 12) between the ages of 1 day to 65 years (66% male), 92 patients between the age group 5 m to 13 years (70% male) were from Pakistan (Gaucher: 55, MPS-I: 31, Pompe: 5, and Fabry: 1), and 5 patients were from Sri Lanka (Gaucher: 3, MPS-I: 1, and Pompe: 1,) in the age group 1–5 years (60% male). One case of MPS-I (2 years/F) was diagnosed from Bangladesh. Of 54 diagnosed cases from India, 22 positive cases with enzyme values ≤4% of the normal mean were enrolled for enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) [Gaucher (Cerezyme): 2, Pompe (Myozyme): 12, MPS-I (Aldurazyme): 6, and Fabry (Fabrazyme): 2]. At present, three Pakistani patients of Gaucher with enzyme values 12–14% of the normal mean are on Cerezyme therapy.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of diagnosed cases of lysosomal storage disorders (n = 307) with clinical features

Before analyzing DBS samples for diagnostic purposes, reproducibility and robustness of enzyme assays were shown by inter-assay and intra-assay results (%CV: 10–14) obtained within acceptable limits (%CV: <15) for all 18 lysosomal enzymes. In correlation studies of 246 cases (demographic details are given in Table 2), 172 demonstrated 100% concordance between biochemical results of DBS and other biological materials [leukocytes (n = 154), plasma (n = 13), and SF (n = 5)]. Another 74 biochemically diagnosed cases on DBS were confirmed by mutation studies (Table 3). Among 44 affected cases, 38 showed pathogenic mutations in the corresponding gene. The remaining six cases (3 Pompe and 3 MPS-I) with low enzyme activity but no mutations were considered false positives because problems in transportation of liquid blood from remote regions along with financial incapability of patients to reach the laboratory made it difficult to verify the enzyme in leukocytes. As a result, overall study has 100% sensitivity (false negatives – nil), 95.2% specificity, and 97.6% diagnostic accuracy for Gaucher, Fabry, Pompe, Tay Sachs, Sandhoff, Niemann Pick, GM1, Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), Fucosidosis, Mannosidosis, Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) type I, II, IIIb, IVa, VI, VII, and I-Cell diseases.

Table 2.

Demographic details of the cases (n = 246) used in correlation studies

| Diseases with enzyme | Total cases | Countries | Region | Cases | Age | Gender | Positive | Normal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaucher (β-glucosidase) | 54 | India | North India | 23 | 3 months–7 years | 12 M, 11 F | 15 | 8 |

| South India | 13 | 1–10 years | 7 M, 6 F | 8 | 5 | |||

| East India | 1 | 13 years | F | 1 | 0 | |||

| West India | 3 | 2–5 years | 1 M, 2 F | 2 | 1 | |||

| Pakistan | 11 | 11 months–13 years | 8 M, 3 F | 9 | 2 | |||

| Sri Lanka | 3 | 2.6–9 years | 3 M | 2 | 1 | |||

| Pompe (α-glucosidase) | 35 | India | North India | 10 | 10 months–35 years | 8 M, 2 F | 3 | 7 |

| South India | 15 | 3 months–22 years | 7 M, 8 F | 8 | 7 | |||

| East India | 2 | 9 months–1 year | 2 F | 2 | 0 | |||

| West India | 5 | 5–12 years | 4 M, 1 F | 3 | 2 | |||

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 year | M | 1 | 0 | |||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 6 years, 7 years | 2 F | 0 | 2 | |||

| Fabry (α-galactosidase) | 11 | India | North India | 7 | 8–65 years | 4 M, 3 F | 2 | 4 |

| South India | 4 | 11–35 years | 3 M, 1 F | 1 | 4 | |||

| Tay Sachs (β-hexosaminidase A) | 14 | India | North India | 9 | 3 months–2.5 years | 6 M, 3 F | 6 | 3 |

| South India | 5 | 6 months–4 years | 3 M, 2 F | 3 | 2 | |||

| Sandhoff (Total hexosaminidase) | 10 | India | North India | 4 | 1–3.5 years | 2 M, 2 F | 2 | 2 |

| South India | 3 | 2–4 years | 1 M, 2 F | 2 | 1 | |||

| West India | 3 | 3–5 years | 2 M, 1 F | 1 | 2 | |||

| GM1 (β-galactosidase) | 11 | India | North India | 8 | 1–5 years | 4 M, 4 F | 4 | 4 |

| West India | 3 | 1.5–8 years | 3 M | 2 | 1 | |||

| Niemann Pick (sphingomyelinase) | 5 | India | North India | 5 | 2.5 months–2.5 years | 3 M, 2 F | 3 | 2 |

| NCL1 (Infantile) (palmitoyl-protein thioesterase) | 10 | India | North India | 4 | 1–3 years | 1 M, 3 F | 2 | 2 |

| South India | 6 | 4 months–1 year | 3 M, 3 F | 3 | 3 | |||

| NCL2 (late infantile) (tripeptidyl peptidase) | 8 | India | North India | 8 | 7–15 years | 6 M, 2 F | 3 | 5 |

| Fucosidosis (α-fucosidase) | 7 | India | North India | 5 | 2–4 years | 2 M, 3 F | 2 | 3 |

| East India | 2 | 1–3 years | 2 M | 0 | 2 | |||

| Mannosidosis (α-mannosidase) | 5 | India | North India | 5 | 3.5–8 years | 3 M, 2 F | 0 | 5 |

| MPS-I (α-iduronidase) | 25 | India | North India | 8 | 2–4.5 years | 3 M, 3 F | 4 | 4 |

| South India | 9 | 1–13 years | 4 M, 5 F | 6 | 3 | |||

| Pakistan | 6 | 1–15 years | 3 M, 3 F | 3 | 3 | |||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 1–1.6 years | 1 M, 1 F | 0 | 2 | |||

| MPS-II (iduronate 2 sulfatase) | 10 | India | North India | 5 | 1–12 years | 4 M, 1 F | 4 | 1 |

| West India | 5 | 2.5–15 years | 4 M, 1 F | 1 | 4 | |||

| MPS-IIIb (α-hexosaminidase) | 9 | India | North India | 5 | 2–5 years | 2 M, 3 F | 0 | 5 |

| South India | 4 | 2–2.5 years | 2 M, 2 F | 2 | 2 | |||

| MPS-IVa (galactose 6-sulfatase) | 10 | India | North India | 5 | 2–7 years | 4 M, 1 F | 3 | 2 |

| South India | 5 | 5–10 years | 2 M, 3 F | 2 | 3 | |||

| MPS-VI (aryl sulfatase B) | 11 | India | North India | 4 | 6 months–6 years | 2 M, 2 F | 2 | 2 |

| South India | 5 | 1–5.3 years | 3 M, 2 F | 2 | 3 | |||

| East India | 2 | 1.5–2.5 years | 2 F | 2 | 0 | |||

| MPS-VII (β-glucuronidase) | 8 | India | North India | 5 | 12–18 years | 4 M, 1 F | 1 | 2 |

| West India | 3 | 14–23 years | 3 F | 2 | 3 | |||

| I-Cell | 3 | India | North India | 3 | 3–5 years | 3 F | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 246 | 246 | 127 | 119 |

Table 3.

Correlation studies (n = 246): DBS with other biological samples using same enzymatic assays (A), DBS with biomarkers status (B), and DBS biochemical diagnoses with molecular diagnoses (C)

| Diseases with enzyme | Total cases | Diagnoses | DBSa nmol/h/mL | Biological samples | Biomarkers/metabolites on DBS/plasma/serum/urine (n = 95) | Mutation/sequence data (n = 74) | Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes/plasma/skin fibroblast (n = 172) | Ref. interval nmol/h/mg | |||||||

| (A) | (B) | (C) | ||||||

| Gaucher (β-glucosidase) | 54 | Affected (n = 37) | (n = 37): 0.062–1.87 | (n = 12): 1.8–4.5 (β-glucosidase in leuko.) | Leuko.: 0.062–6.0 | DBS – CHT (n = 23): 151–3,425 | Total (n = 25): | FP and FN – not found |

| DBS-CHT:>100.0 nmol/h/mL | (n = 2): 0.013, 6.29 | [n = 16]-L444P (homozygous), | 54/54 = (100% satisfactory) | |||||

| Pl.- CHT: >150 nmol/h/mL | Pl. – CHT (n = 12): 433–4,251.0 | [n = 3]- F2131 (TTT-ATT) (homozygous), | ||||||

| [n = 6]- {S356F (homozygous), L444P/S42N, L444P (homozygous)/A456P (heterozygous), L444P (heterozygous)/S356F (homozygous), L420(CTT->CTA), R120W(CGG->TGG)(heterozygous)/E326K(GAG->AAG)} | ||||||||

| Normal (n = 17) | (n = 17): 2.0–8.1 | (n = 13): 11.2–43.2 9 (β-glucosidase in leukocytes) | Leuko.: 10–84.0 | DBS – CHT (n = 4): 4.5–43.2 | (n = 4): Mutation not available | |||

| DBS-CHT: <100 | Pl. – CHT (n = 1): 2.9 | |||||||

| Pl.-CHT <150.0 | ||||||||

| Pompe (α-glucosidase) | 35 | Affected (n = 17) | (n = 17) : 0.005–0.16 (ratio) | Leukocytes (n = 5): <0.2 (ratio) | <0.22 (ratio) | Serum CK: (n = 8): Raised | (n = 6): (homozygous) c.1799G>A, (homozygous) c.1820G>A, (homozygous) c.1447G>A, (heterozygous) c.1726G>A/c.2065G>A, (heterozygous) c.2780C>T/c.2783A>G, (homozygous) c.2560C>T | FPb – three, FN – not found |

| Skin fibroblast: (n = 3): 0.062–0.89 | 0.062–5.0 | (n = 3): Mutation not available (FP) | 32/35 = (91.4% satisfactory) | |||||

| Normal (n = 18) | (n = 18):0.25–0.8 (ratio) | Leukocytes (n = 5): 0.31–0.62 (ratio) | 0.25–0.75 (ratio) | (n = 11): CK raised in four | (n = 8): Mutation not available | |||

| (n = 5): (Heterozygous) c. 2780C>T | ||||||||

| Fabry (α-galactosidase) | 11 | Affected (n = 3) | (n = 3): 0.062–1.0 | (n = 3): 0.062–2.0 | 0.062–4.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 8) | (n = 8): 3.2–5.23 | (n = 5) 25–59.4 | 22–85.5 | No biomarker | (n = 1): (Heterozygous) c.166T>C, | 11/11 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| (n = 2): Mutation not available | ||||||||

| Tay Sachs (β-hexosaminidase A) | 14 | Affected (n = 9) | (n = 9):0.062–3.4 | (n = 5): 0.062–2.54 | 0.062–5.4 | No biomarker | (n = 4): 1277_1278insTATC/1277_1278insTATC | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 28.9–90.6 | (n = 5): 95–264 | 74–323 | No biomarker | Not done | 14/14 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| Sandhoff (total hexosaminidase) | 10 | Affected (n = 5) | (n = 5): 0.062–2.1 | Plasma (n = 5) : 0.062–312 | 0.062–330 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 31–228.1 | Plasma enzyme (n = 5): 800–2,250 | 660–5,000 | No biomarker | Not done | 10/10 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| GM1 (β-galactosidase) | 11 | Affected (n = 6) | (n = 6): 0.062–1.29 | (n = 6) : 0.062–8.3 | 0.062–14 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 23–63.08 | (n = 5): 65–494.9 | 58–676 | No biomarker | Not done | 11/11 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| Niemann Pick (A/B) (sphingomyelinase) | 5 | Affected (n = 2) | (n = 2): 0.062–0.75 | (n = 2): 0.062–3.5 (nmol/17 h/mg) | 0.062–5.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 3) | (n = 3): 4.5–21.4 | (n = 3): 13.7–18.2 (nmol/17 h/mg) | 10–32 | No biomarker | Not done | 5/5 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL-infantile) (PPT) | 10 | Affected (n = 5) | (n = 5): 0.062–2.6 | (n = 5): 0.062–12.0 | 0.062–13 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 5.8–9.2 | (n = 5): 102–204.0 (nmol/17 h/mg) | 25–224.0 | No biomarker | Not done | 10/10 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL-late infantile) (TPP) | 8 | Affected (n = 3) | (n = 3): 0.062–3.52 | (n = 3): 0.062–1.2 | 0.062–10 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 35.5–61.2 | (n = 5): 36–74 | 25–198 | No biomarker | Not done | 8/8 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| Fucosidosis (α-fucosidase) | 7 | Affected (n = 2) | (n = 2): 0.062–0.23 | (n = 2): 0.062–0.098 | 0.062–2.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 32–45.95 | (n = 5): 243–512.5 | 200–735.0 | No biomarker | Not done | 7/7 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| Mannosidosis (α-mannosidase) | 5 | Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 32–59.0 | (n = 5): 54–229.0 | 40.0–398.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| 5/5 = 100% satisfactory | ||||||||

| MPS-I (α-iduronidase) | 25 | Affected (n = 13) | (n = 13); 0.062–0.71 | (n = 5): 0.062–1.2 | 0.062–3.0 | (n = 10): Raised GAGS, | (n = 2): (Homozygous) c.223G>A/c.299+1G>A | FPb – Three, FN – not found |

| Skin fibroblast: (n = 2):13.5, 20.0 | 0.062–25.0 | (n = 3): EP positive: (Dermatan sulfate + Heparan sulfate) | (n = 1): (Homozygous) c.314G>A | 3/25 = 88% satisfactory | ||||

| (n = 3): Mutation not available (FP) | ||||||||

| Normal (n = 12) | (n = 12): 1.45–7.26 | (n = 5): 37.5–147.85 | 21–150.0 | (n = 7): Normal EP | (n = 6): Mutation not available | |||

| (n = 1): (Heterozygous) c.314G>A | ||||||||

| MPS-II (Iduronate-2-sulfatase) | 10 | Affected (n = 5) | (n = 5): 0.062–5.0 | (n = 5): 0.062–4.2 (nmol/4 h/mg) | 0.062–5.0 | (n = 3): Raised GAGs | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 12–25.5 | (n = 5): 19.9–45.5 | 18–94.0 | (n = 3): Normal GAGs | Not done | 10/10 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| MPS-IIIb (α-hexosaminidase) | 9 | Affected (n = 2) | (n = 2): 0.062, 0.09 | (n = 2): 0.062, 0.2 (nmol/17h/mg) | 0.062–1.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 7) | (n = 7): 2.8-3.5 | (n = 5): 37–77.3 | 31–102 | (n = 2): GAGs normal | (n = 2): Mutation not available | 9/9 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| MPS-IVa (galactose 6 sulfatase) | 10 | Affected (n = 5) | (n = 5): 0.062–0.57 | (n = 5):0.062–0.24 (nmol/17 h/mg) | 0.062–5.0 | (n = 5): Raised GAGs | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5): 10.3–20.5 | (n = 5): 59–236.85 | 45–443.0 | No biomarker | Not done | 10/10 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| MPS-VI (Aryl sulfatase B) | 11 | Affected (n = 5) | (n = 5): 0.062–0.93 | (n = 5): 0.062–3.99 | 0.062–6.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 6) | (n = 6): 7–32.0 | (n = 5): 43.4–121.0 | 14–133 | (n = 1): GAGs normal | (n = 1): Mutation not available | 11/11 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| MPS-VII (β-glucuronidase) | 8 | Affected (n = 3) | (n = 3): 0.062–2.5 | (n = 3): 0.062–15 | 0.062–20.0 | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| Normal (n = 5) | (n = 5):3.9–25.32 | (n = 5): 85–218.5 | 72.7–777.7 | No biomarker | Not done | 8/8 = 100% satisfactory | ||

| I-Cell (α-iduronidase, β hexosaminidase A, β-glucuronidase) | 3 | Affected (n = 3) | (n = 3): Raised enzymes | (n = 3): Plasma enzymes raised | Plasma range is different for different enzymes | No biomarker | Not done | FP and FN – not found |

| 3/3 = 100% satisfactory | ||||||||

| Total | 246 | 246 | (n = 172) | (n = 95) (overlapping of A & C) | (n = 74) | Correct analysis: 240/246 | ||

| (97.6% accuracy) | ||||||||

PPT palmitoyl-protein thioesterase, TPP tripeptidyl peptidase, GAGS glycosaminoglycans, EP urine MPS electrophoresis, Pl. Plasma, Leuko leukocytes, CHT chitotriosidase, FP false positive, FN false negative

Pl. Note: In the present study, primarily cases of Gaucher, Pompe, MPS-I, and Fabry were chosen for molecular confirmation because treatment is commercially available for these disorders [Genzyme (India), a Sanofi company]; however, some cases of Tay Sachs, MPS-VI, and MPS-IIIb were also included. Confirmation of DBS results in leukocytes/skin fibroblasts was not possible always as samples were transported from different countries and transportation of liquid samples was a big hurdle. The prohibitive cost of gene sequencing and insufficient samples has been the main reasons for not confirming all biochemically diagnosed cases by molecular studies

a Reference intervals for DBS are given in Table 1

bFalse positive samples after molecular confirmation were not tested in leukocytes (gold standard assay) due to cross-border liquid blood transportation problem. However, second control enzyme was tested to check the sample integrity. Hence, with no other option to verify, these samples were considered false positives to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of DBS assays

In the study on biomarkers, 35 out of 37 positive cases of Gaucher showed high chitotriosidase level while 2 were normal (Table 3). Similarly, eight cases with raised CK were biochemically affected for Pompe disease. All MPS-I affected cases (n = 13) either showed increased GAGs or disease specific band profiles on urine MPS electrophoresis. In three cases with α-iduronidase deficiency where raised GAGs and bands of dermatan sulfate and heparan sulfate were detected, mutation for MPS-I was not found. No biomarker was studied in patients of other disorders.

The overall satisfactory performance (91.7% correct analysis) in pilot study (DBS-lysosomal enzymes), ERNDIM further ensured testing quality of DBS assays. This includes accurate diagnosis of Fabry, Hunter, Hurler, Gaucher, Pompe, MPS-IIIb, and late infantile-NCL patients with one false negative (Krabbe) and four false positives (Krabbe, Metachromatic leukodystrophy, MPS-IVa, and normal control).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates 100% sensitivity and 95.2% specificity of DBS enzyme assays to diagnose LSDs using modified protocols. One of the primary modifications was substitution of water for buffer to elute sample from filter paper, which has proven to be cost effective without compromising testing quality. Substrate (4MU sulfate) specificity for aryl sulfatase B was enhanced by including barium acetate in the buffer. Barium ions are a potential inhibitor of aryl sulfatase A (Bostick et al. 1978). For estimation of acid sphingomyelinase (ASM), 4MU bound fluorogenic substrate was used along with saccharolactone to inhibit the activity of β-glucuronidase since radio-labelled substrate used by Civallero et al. (2006) can cause health hazards. The procedures were further simplified by stopping reactions with 2-amino, 2-methyl, 1-propanol (0.1 M), pH 10.6 instead of more commonly used glycine-carbonate buffer, pH 9.6 (Willey et al. 1982). It is easy to prepare, stable for at least 6 months at room temperature without change in pH and microbial growth, and fluorescence remains stable up to 1 h at room temperature after stopping the reaction. The advantage of easy collection, transportation, storage, and dispatching of DBS especially from remote regions lacking specialized laboratories has been highlighted in this study which involved cross-country transportation of DBS samples. The reference intervals established for enzyme activities effectively discriminate between affected and normal subjects in South Asian population (Table 1). In most of the affected cases, enzyme activity was <8% of the normal mean except for Gaucher, Infantile-NCL, MPS II (16–24%), and Pompe (% ratio 25). Therefore, in the cases where enzyme activity remains 20–40% of normal mean, we recommend confirmatory testing (either in leukocytes or mutation studies).

Civallero et al. (2006) reported estimation of 12 lysosomal enzymes on DBS; however, their results were not validated with testing in other biological materials or biomarkers or molecular diagnosis. In the present study, these methods were used to validate the results achieved by using modified protocols. Absolute concordance was seen in Gaucher, Fabry, Tay Sachs, Sandhoff, Niemann Pick, GM1, Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), Fucosidosis, Mannosidosis, MPS II, IIIb, IVa, VI, VII, and I-Cell diseases while 91.4% and 88% concordance was observed for Pompe and MPS-I, respectively. The six false positive results (unable to confirm in leukocytes) could be on account of mutations that were not detected by conventional sequencing or deterioration of enzyme (α-iduronidase being more sensitive to high temperature and humidity) in transportation as temperature in Indian Subcontinent varies between 35°C and 45°C during summer, and the mean duration of sample transportation was 10–12 days.

Diagnosis of Pompe disease was made by considering the ratio of activities of lysosomal acid α-glucosidase to total acid α-glucosidase. In a number of our cases where individual values of lysosomal and total acid α-glucosidase were low, the ratio fell into the normal range. In view of normal ratio, these cases (poor controls) should be considered as normal and analyzed on the basis of an additional range set in our study (Table 1). Their unaffected status has been further proven by the absence of pathogenic mutations.

Recently, Cobos et al. (2015) suggested for correlating biochemical results with a second enzyme assay and/or mutation study. They reported mutations in 64.7%, 100%, 100%, and 62.5% patients that were putatively diagnosed by biochemical tests for MPS I, II, VI, and mucolipidosis II/III, respectively. Absence of pathognomonic IDUA mutations in two cases with low α-iduronidase activity was ascribed to the fact that aside from false positive results, certain mutations that may impact enzyme activity including exon spanning inversions, duplications, or deep intronic mutations are not detected by conventional sequencing. Similarly, in our study, untraceable mutations could be one of the reasons for false positives.

Another approach to corroborate our results on DBS was to demonstrate correlation with related biomarkers (Table 3). The raised level of CHT in all except two patients afflicted with Gaucher supports its relevance as a prognostic marker for disease progression. Normal chitotriosidase activity with low β-glucosidase activity can be explained by highly prevalent CHIT1 null polymorphism in 5–6% of Gaucher patients (Hollak et al. 1994). Normal mutation results in three of MPS-I cases with increased GAGs in MPS quantification/abnormal electrophoretic pattern in urine could in fact be patients suffering from another type of MPS where deficiency of α-iduronidase could be explained by low enzyme stability or undetectable mutations as described above. Similarly, elevated CK levels in biochemically diagnosed Pompe patients were significantly associated with Pompe disease.

Success of DBS technology in diagnosis of LSDs is underpinned by validation through participation in EQAS schemes. Importantly, our experience emphasizes the need for individual laboratories to establish and validate their own biological reference intervals for affected and normal subjects by analyzing a large number of samples so as to take into account varying local environmental and laboratory conditions as well as different ethnicities. In comparison to MS/MS technology with multiplex ability (Chace et al. 2003), our modified DBS methods are simple, sensitive, and inexpensive to set up. In addition, in developing countries, diagnoses are made on a case to case basis by relying on clinical phenotypes and laboratory test results. As a consequence, biochemical diagnosis of LSDs by single analyte analysis remains the preferable approach for reliable diagnosis of LSDs.

In India, the most prevalent LSDs were found to be Gaucher, Pompe, and MPS-I accounting for 38%, 25%, and 14.3% of the patients, respectively, in accordance with earlier studies (Verma et al. 2012; Sheth et al. 2014). In comparison to Pompe and Fabry, a higher incidence of Gaucher (60%) and MPS-I (34%) was seen among patients from Pakistan. Pathogenic mutation L444P was detected in all Gaucher positive cases from Pakistan. Traditional consanguinity in Pakistan may be one of the contributing factors to the high prevalence of these LSDs in comparison to other South Asian countries.

Patients presenting with one or more clinical features presented for a particular disease in Fig. 1 should be investigated for LSDs. Bilateral fundal cherry-red spot was observed in all 12 patients of Tay Sachs, 2 of Sandhoff, and 12 of GM1 Gangliosidosis disease. All 25 cases who are currently receiving ERT have demonstrated a gradual amelioration of symptoms. In many patients ERT has been transformative and even life-saving; in others, however, the impact has been limited, often due to delay in starting therapy. Unfortunately access to enzyme therapy in India and South East Asia as a whole is severely limited due to the lack of central state funding, as occurs for rare diseases in other counties.

We recommend the utilization of DBS-based fluorescent enzyme assays as diagnostic tools for timely identification of LSDs patients accurately; however, where feasible, molecular testing on DNA isolated from the same DBS is encouraged as part of the diagnosis.

Acknowledgement

We thank all patients and normal subjects whose blood was used as a control/reference material to generate the data for this study. We extend our thanks to Genzyme (India) who has chosen our center as a referral laboratory for lysosomal enzymes testing. We express our gratitude to doctors from India and neighboring countries for referring patients to our genetic center. We appreciate Genzyme (India), a Sanofi company for extending support to patients for testing and treatment. We also thank Chairman and Director Administration, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, for their cooperation in setting up genetic testing facility.

Abbreviations

- CK

Creatine phosphokinase

- DBS

Dried blood spot

- EQAS

External Quality Assurance Scheme

- ERNDIM

European Research Network for evaluation and improvement of screening, diagnosis, and treatment of inborn errors of metabolism

- GAGs

Glycosaminoglycans

- LSDs

Lysosomal storage disorders

- MPS

Mucopolysaccharidosis

Take Home Message

Dried blood spots (DBS) have potential to substitute the established liquid bio-matrices (plasma/leukocytes/cultured fibroblasts) for reliable, accurate, and timely diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) as demonstrated by 100% sensitivity and 95.2% specificity obtained after biochemical (using liquid biological samples) and molecular confirmation of the DBS-based enzymatic diagnoses to facilitate prognostication and genetic counseling and its implementation will also overcome challenges in cross-country transportation of conventional biological samples.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Authors’ contribution

Concept, design, and method standardization: Jyotsna Verma

Experimentation/Acquisition of data/analysis/interpretation: Jyotsna Verma, Divya C. Thomas, Sandeepika Sharma, Pramod K. Mistry, David C. Kasper

Patients’ management/clinical assessment: I. C. Verma, Sunita Bijarnia, Ratna D. Puri

Drafting article or revising or reviewing it critically for important content: Jyotsna Verma, Divya C. Thomas, Pramod K. Mistry, David C. Kasper, I. C. Verma, Ratna D. Puri

Final approval for publication: All authors

Conflict of Interest

Jyotsna Verma and David C. Kasper received travel grant from Genzyme, a Sanofi company. Same company also supported I. C. Verma for organization of continuing medical education (CME). Divya C. Thomas, Sandeepika Sharma, Ratna D. Puri, Sunita Bijarnia-Mahay, and Pramod K. Mistry declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5) of the World Medical Association. Informed consent was obtained from all patients/normal subjects for being included in the study.

Funding

Patients for enzymatic testing of four disorders (Pompe, Gaucher, Fabry, and MPS1) were sponsored by Genzyme (India), a Sanofi company via doctors from India and other neighboring countries to help in providing treatment on compassionate ground under their “India Compassionate Access Program.” Genzyme has under no circumstance extended funds to us under any project head/grant number nor has it provided us with any financial support to facilitate the functioning of our laboratory so as to influence the results of our study.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Contributor Information

Jyotsna Verma, Email: j4verma@yahoo.com.

Collaborators: Matthias R. Baumgartner, Marc Patterson, Shamima Rahman, Verena Peters, Eva Morava, and Johannes Zschocke

References

- Bostick WD, Dlnsmore SR, Mrochek JE, Waalkes TP. Separation and analysis of aryl sulfatase isoenzymes in body fluids of man. Clin Chem. 1978;24(8):1305–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burin M, Dutra-Filho C, Brum J, Mauricio T, Amorim M, Giugliani R. Effect of collection, transport, processing and storage of blood specimens on the activity of lysosomal enzymes in plasma and leukocytes. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:1003–1013. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2000000900003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camelier MV, Burin MG, De Mari J, Vieira TA, Marasca G, Giugliani R. Practical and reliable enzyme test for the detection of Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio Syndrome type A) in dried blood samples. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:1805–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceci R, de Francesco PN, Mucci JM, Cancelarich LN, Fossati CA, Rozenfeld PA. Reliability of enzyme assays in dried blood spots for diagnosis of 4 lysosomal storage disorders. Adv Biol Chem. 2011;1:58–64. doi: 10.4236/abc.2011.13008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chace DH, Kalas TA, Naylor EW. Use of tandem mass spectrometry for multianalyte screening of dried blood specimens from newborns. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1797–1817. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D. Fabry disease: enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;308:195–196. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Gaucher and Niemann-Pick diseases- enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper: retrospective diagnosis in newborn- screening cards. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;317:191–197. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00798-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff diseases: enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper: retrospective diagnosis in newborn-screening cards. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;318(1–2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civallero G, Michelin K, de Mari J, et al. Twelve different enzyme assays on dried-blood filter paper samples for detection of patients with selected inherited lysosomal storage diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;372:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos PN, Steqlich C, Santer R, Lukacs Z, Gal A. Dried blood spots allow targeted screening to diagnose mucopolysaccharidosis and mucolipidosis. JIMD Rep. 2015;15:123–132. doi: 10.1007/8904_2014_308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho J, Guigliani R. Fibroblasts of skin fragments as a tool for the investigation of genetics diseases: technical recommendations. Genet Mol Biol. 2000;23:269–271. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572000000200004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filocamo M, Morrone A. Lysosomal storage disorders: molecular basis and laboratory testing. Hum Genomics. 2011;5:156–169. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-3-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollak CE, Van Weely S, van Oers MH, Aerts JM. Marked elevation of plasma chitotriosidase activity. A novel hallmark of Gaucher disease. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1288–1292. doi: 10.1172/JCI117084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood JJ, Muller V, Smithson A, Baggett N. A fluorometric assay using 4 methylumbelliferyl alpha-L-iduronide for the estimation of alpha-L-iduronidase activity and the detection of Hurler & Scheie syndromes. Clin Chim Acta. 1979;92:257–265. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(79)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky P, Lidove O. Current therapeutic strategies in lysosomal disorders. Presse Med. 2014;43:1174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. Biochemical methods in medical genetics. 18. Springfield: Thomas; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs Z, Santavuori P, Keil A, Steinfeld R, Kohlschutter A. Rapid and simple assay for the determination of tripeptidyl peptidase and palmitoyl protein thioesterase activities in dried blood spots. Clin Chem. 2003;49:509–511. doi: 10.1373/49.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J, Fensom AH. 4 Methylumbelliferyl α-N-acetyl glucosaminidase activity for diagnosis of Sanfilippo B disease. Clin Genet. 1985;27:258–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistri M, Oza N, Sheth F, Sheth J. Prenatal diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders: our experience in 120 cases. Mol Cytogenet. 2014;7(Suppl 1):P126. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-7-S1-P126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller KB, Rodrigues MD, Pereira VG, Martins AM, D’Almeida V. Reference values for lysosomal enzymes activities using dried blood spots samples- a Brazilian experience. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:65–72. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-5-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth J, Mistri M, Sheth F, et al. Burden of lysosomal storage disorders in India: experience of 387 affected children from a single diagnostic facility. JIMD Rep. 2014;12:51–63. doi: 10.1007/8904_2013_244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Diggelen OP, Keulemans JL, Winchester B, et al. A rapid fluorogenic palmitoyl-protein thioesterase assay: pre- and postnatal diagnosis of INCL. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;66:240–244. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Diggelen OP, Voznyi YV, Keulemans JLM, et al. A new fluorometric enzyme assay for the diagnosis of Niemann–Pick A/B, with specificity of natural sphingomyelinase substrate. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28:733–741. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-0105-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma PK, Ranganath P, Dalal AB, Phadke SR. Spectrum of lysosomal storage disorders at a medical genetics center in northern India. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:799–804. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma J, Thomas DC, Sharma S, et al. Inherited metabolic disorders: quality management for laboratory diagnosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;447:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voznyi YV, Keulemans JLM, van Diggelen OP. A fluorimetric enzyme assay for the diagnosis of MPS II (Hunter disease) J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24:675–680. doi: 10.1023/A:1012763026526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey AM, Carter TP, Kally S, et al. Clinical genetics: problems in diagnoses and counseling. New York/London: Harcourt Brace/Jovanovich; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Winchester B, Bali D, Bodamer OA, et al. Methods for a prompt and reliable laboratory diagnosis of Pompe disease: report from an international consensus meeting. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]