Abstract

Background

Nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma is a rarely diagnosed and potentially under-recognized type of squamous carcinoma that is considered one of the most aggressive human solid tumors. Alpha-fetoprotein elevation has been associated with chronic liver diseases and a limited number of cancers. In particular, in presence of a mediastinal mass in a young man, alpha-fetoprotein elevation is considered nearly pathognomonic of a non-seminoma germ-cell tumor.

Case presentation

A 22-year old man without any comorbidity was diagnosed with a large mediastinal mass with skeletal and lymph node metastases. The clinical picture was dominated by a life-threatening superior vena cava syndrome with elevated alpha-fetoprotein and lactate dehydrogenase that supported the diagnostic suspicion of mediastinal germ-cell tumor. However, a biopsy showed a poorly-differentiated and diffusely necrotic carcinoma. We eventually reached the diagnosis of the peculiar entity of NUT midline carcinoma, but the differential diagnosis was quite challenging also because alpha-fetoprotein is not reported as a marker of NUT midline carcinoma. Notably, alpha-fetoprotein levels correlated with disease course.

Conclusions

The life-threatening aggressiveness of NUT midline carcinoma mandates to reach the right diagnosis in the shortest possible time. In this regard, poorly differentiated carcinomas lacking glandular differentiation mandate testing for NUT expression by immunohistochemistry. Awareness of a potentially misleading tumor marker elevation can help to broaden the differential diagnosis and establish the most appropriate treatment.

Keywords: NUT midline carcinoma, Mediastinal mass, Alpha–fetoprotein, Case report

Background

Nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma is an exceedingly rare subtype of squamous poorly–differentiated carcinoma and is considered one of the most aggressive human solid tumors [1–3]. NUT midline carcinoma is a relatively new entity, that may likely be under–recognized and under–diagnosed. All ages and organs might be affected, but most frequently NUT midline carcinoma arises along the trunk or the head and, in particular, in midline structures such as the mediastinum [1–3]. NUT midline carcinoma is characterized by the pathognomonic chromosomal rearrangement between the NUT gene with either bromodomain–containing protein 4 (BRD4) or, less frequently, with BRD3 (on chromosome 9), leading to the fusion genes BRD4–NUT or BRD3–NUT, respectively [1–3]. BRD is a DNA reader that activates transcription by binding to acetyl–modified lysine residues of histone tails [1, 3, 4]. The expression of several oncogenes, including transcription factors and MYC, is epigenetically regulated by BRD. More recently, a novel fusion gene between the methyl-transferase protein NSD3 on chromosome 8 and NUT has been reported (NSD3–NUT) [1, 5, 6]. NSD3 has shown to be associated with the extraterminal domains of BET proteins, which serves as a key component in the BRD–NUT oncogene complex [1]. Moreover, two novel three–way translocations [t(9;15;19;q34;q13;p13.1), and t(4;15;19)(q13;q14;p13.1)] have been described [5, 6]. NUT rearrangement has been suggested to possibily represent a tumor–initiating event. Its importance in the pathogenesis of NUT midline carcinoma is further supported by the evidences that withdrawal of the NUT fusion protein resulted in a dramatic and irreversible squamous differentiation and growth arrest, thus demonstrating that the BRD–NUT protein blocks differentiation [7].

Alpha–fetoprotein elevation has been associated with chronic liver diseases and a limited number of cancers (hepatic primary tumors and metastases, bile duct, pancreatic, gastric and lung cancer, and non–seminoma germ–cell tumors). Moreover, in presence of testicular or mediastinal mass an elevated alpha–fetoprotein strongly suggests a non–seminoma germ–cell tumor especially in young patients.

Case presentation

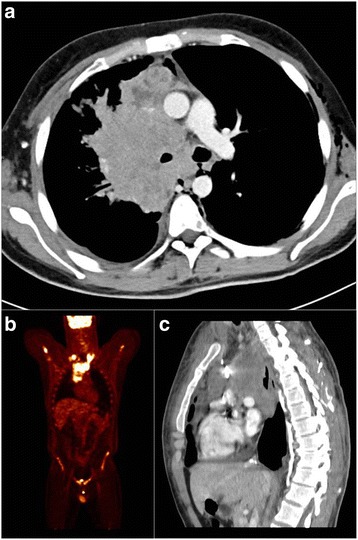

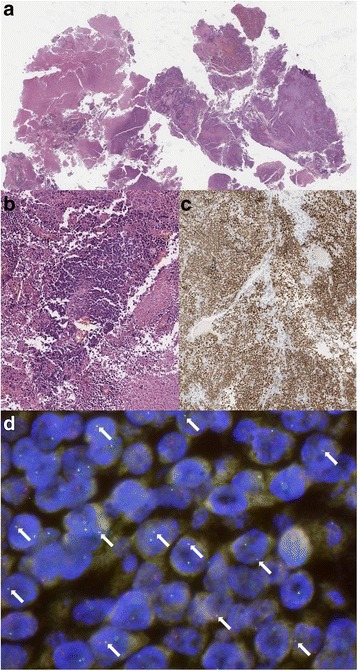

A 22–year old man was referred to our center because of a large mediastinal mass along with skeletal and lymph node metastases. The clinical picture was dominated by shortness of breath due to severe superior vena cava syndrome with pleural–pericardial effusion (Fig. 1 panels a, b, c). Laboratory tests showed elevated alpha–fetoprotein (765 ng/mL; normal value <10.9 ng/mL) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) = 14,468 U/L (normal range 240–480 U/L). Taken altogether these findings strongly suggested a mediastinal non–seminoma germ cell tumor (GCT) [7] but, unexpectedly, a biopsy of a supraclavicular enlarged lymph node revealed a poorly differentiated and diffusely necrotic carcinoma (Fig. 2, panels a, b). Immunohistochemistry was weakly positive for AE1–AE3 cytokeratin pool, TTF–1, p63, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD34 and, focally, EMA and cytokeratin 7, but negative for PLAP, alpha–fetoprotein, beta–HCG, CD30, CD3, CD20, CD117, Melan–A, S100 protein, ALK, PAX8, and desmin, thereby ruling out GCT (Table.1 describes detailed immunohistochemistry profile and clues to diagnosis suggested by each immunohistochemical marker) [7]. Due to such peculiar presentation and the high levels of alpha–fetoprotein, a second pathology opinion was requested. GCT was again excluded and a diagnosis of poorly differentiated large cell carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation was rendered. However, taking advantage of the clinical presentation and the patient’s young age, in a third consultation, a monoclonal antibody against NUT protein was used (Fig. 2, panel c) [8] along with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for NUT–BRD4 translocation [3]. Tumor cells revealed diffuse decoration for NUT protein and FISH analysis confirmed the occurrence of t(15;19) BRD4–NUT translocation (Fig. 2 panel d), thereby establishing the diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma [1, 3].

Fig. 1.

Disease status at diagnosis. Panel a, c: CT scan showing bulky mediastinal mass with involvemente of right lung ilum, compression of the right superior bronchus, and dislocation of the trachea and right intermediate bronchus with pleural and pericardial effusion (panel a axial, panel c sagittal). Panel b: PET scan showing supraclavicular involvement of the disease and absence of liver metastases. CT, computed tomography; PET positron emission tomography

Fig. 2.

Pathology images. Panel a, b: Hematoxilin and eosin stain (panel a 20X magnification, panel b 40X magnification). NUT carcinoma typically shows sheets of monomorphic round to ovoid cells with scant pale eosinophilic to basophilic cytoplasm; nuclei with irregular outlines and slightly coarse chromatin with small nucleoli. Necrosis, mitotic figures and crush artefact are common. Panel c: diffuse nuclear immunohistochemical staining with nuclear protein in testis (NUT) antibody (40X magnification). NUT (C52B1, CELL Signaling, Technology) Rabbit mAb detects endogenous levels of total NUT protein. The antibody also detects levels of BRD4-Nut fusion protein. Panel d: FISH showing positivity for NUT-BRD4 fusion gene. FISH was performed using dual color single fusion probes: BAC clone (RP11-122P18) spanning NUT gene is labeled in spectrum orange, BAC clone RP11-637P24 covering BRD4 gene is labeled in spectrum green. The presence of the translocation t (15;19)(q14;p13) BRD4/NUT is showed by overlapping of one green and one orange probe signal (white arrows). FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; NUT, nuclear protein in testis; BRD4, bromodomain–containing protein–4; BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome

Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry profile at the time of first evaluation

| Weakly positive | Clues to diagnosis (if positive) | Negative | Clues to diagnosis (if positive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE1-AE3 cytokeratin pool | Carcinomas, GCT (rare), thymoma, mesenchymal tumors | PLAP | Seminoma |

| TTF-1 | Lung, thyroid cancer | AFP | Non-seminoma GCT, HCC, pancreas carcinoma |

| p63 | Basal/squamous carcinoma, mesenchymal tumors, lymphomas, adenoid cystic carcinoma, salivary gland tumors, thymoma, thymic carcinoma, breast, urothelial carcinoma | Beta-HCG | Non-seminoma GCT |

| Synaptophysin | Neuroendocrine neoplasms, adrenal gland carcinoma, mesenchymal tumors | CD30 | Lymphomas (HL and NHL), non-seminoma GCT, |

| Chromogranin A | Neuroendocrine tumors | CD3 | T-cell lymphomas |

| CD34 | Hematologic malignances, mesenchymal tumors, papillary thyroid carcinoma, thymoma | CD20 | B-cell lymphomas |

| Focally positive | CD117 | Mesenchymal tumors, GCT, SCLC, leukemias, lymphomas, melanoma | |

| EMA | adenocarcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, mesenchymal tumors, mesothelioma, lymphoma, thymic carcinoma | Melan-A | Melanoma, mesenchymal tumors, adrenal cortical tumors, sex-cord stromal tumors |

| Cytokeratin 7 | Lung cancer and other carcinomas, GCT (rare), mesenchymal tumors | S-100 | Melanoma, mesenchymal tumors, adenoid cystic carcinoma, sex-cord stromal tumors |

| ALK | Lymphomas, NSCLC, mesenchymal tumors, RCC (rare) | ||

| PAX8 | Thymic carcinoma, thymomas, thyroid anaplastic carcinoma, RCC, neuroendocrine neoplasms, seminoma | ||

| Desmin | Mesenchymal tumors |

TTF-1 thyroid transcription factor-1, EMA epithelial membrane antigen, PLAP placental alkaline phosphatase, AFP alpha-fetoprotein, beta-HCG human chorionic gonadotropin, ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase, GCT germ cell tumor, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HL Hodgkin’s lymphoma, NHL Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, RCC renal cell carcinoma, SCLC small cell lung cancer, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer

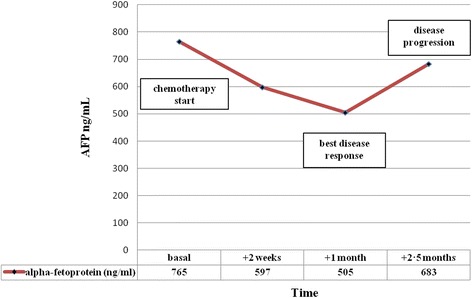

Notably, in our patient alpha–fetoprotein levels directly correlated with disease course. Indeed, in this young gentleman, basal level was 765 u/mL and declined to 505 u/mL after two chemotherapy cycles (cisplatin 25 mg/m2 days 1- > 4, etoposide 100 mg/m2 days 1- > 4) along with a sharp clinical improvement due to attenuation of the superior vena cava syndrome. Unfortunately, clinical benefit was short–lasting and alpha–fetoprotein rose up again at the time of subsequent disease progression (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Alpha-fetoprotein levels and disease course during chemotherapy

Discussion and conclusions

Diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma is quite challenging and demands to be hypothesized and specifically demonstrated. Indeed, microscopic features are quite unspecific and range from completely undifferentiated carcinoma to carcinoma with squamous differentiation and abrupt keratinization that may be either focal or prominent. Tumor cells usually have an epithelioid, medium–size appearance and are in general monomorphic with round to oval nuclei and distinct nucleoli. Further morphologic aspects are a high mitotic rate along with necrosis and neutrophilic infiltrates. Immunohistochemistry with the NUT antibody is positive with a diffuse nuclear staining. However, NUT positivity might be found in GCTs as well and, to be regarded as truly positive, it must be seen in >50% of tumor cells.

Another peculiarity of NUT midline carcinoma is represented by the relatively simple karyotype that often presents the NUT translocation as the only relevant abnormality. This strongly differentiate this tumor from other squamous cell carcinomas that usually harbor highly aberrant and complex karyotypes [9, 10].

Differential diagnosis includes several tumors, encompassing hematologic malignancies or neuroendocrine tumors, because of non–specific morphology and immunohistochemistry profile apart from the pathognomonic NUT protein expression and the characteristic cytogenetic abnormalities [1, 3, 11]. As a general rule, it is recommended to perform immunohistochemistry for NUT protein in all poorly differentiated carcinomas that lack glandular differentiation and whenever the clinical picture is not completely consistent with more frequent tumors (midline or unusual position, young people, no smoking habit, rapid progression upon therapy) [2, 8, 12]. Both clinical history and some pathologic features (i.e., monomorphic tumor cells with abrupt keratinization) might help in generating the suspicion of NUT midline carcinoma. [10–12].

In the absence of hepatic involvement (Fig. 1 panel c), the diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma was particularly challenging in our patient because alpha–fetoprotein has only seldom been reported associated with this tumor [1, 3, 13–16]. Table 2 describes other clinical cases reporting alpha–fetoprotein elevation. Moreover, in NUT midline carcinoma immunohistochemical expression of alpha-fetoprotein is negative, as it was in our patient and in other NUT midline carcinoma cases describing serum alpha-fetoprotein elevation [1, 3, 17]. Interestingly, alpha–fetoprotein levels during treatment were not reported in the majority of the cases, whereas this marker correlated with disease course in our patient. In light of these findings, we suggest not to exclude and, on the contrary, to take into consideration the diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma when facing a patient with fast–growing lump in midline structures and alpha-fetoprotein elevation. Of course, evaluation of alpha–fetoprotein levels in other cases of NUT midline carcinoma might help to better define the role of this serum marker in this challenging disease.

Table 2.

Case reports of NUT midline carcinoma describing alpha–fetoprotein (AFP) elevation

| Authors | Year | Site(s) of disease | Age | Gender | Serum AFP level | IHC AFP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu B et al. | 2011 | Mediastinum, lung | 42 | Male | Elevated | Negative |

| Ball A et al. | 2013 | Mediastinum, pelvis | 19 | Female | Elevated | NA |

| Parikh SA et al. | 2013 | Mediastinum, lung | 36 | Male | Elevated | NA |

| Raza A et al. | 2015 | Mediastinum, lung | 36 | Male | Elevated | Negative |

| Harada Y et al. | 2016 | Mediastinum, lung, bone | 28 | Male | Elevated | NA |

| Present report | 2017 | Mediastinum, lymphnodes, bone | 22 | Male | Elevated | Negative |

IHC immunohistochemistry, NA not available

The observed elevation of alpha–fetoprotein in NUT midline carcinoma might be related to the suggested hypothesis that these cells arise from primitive neural crest–derived cells. [9] Indeed, both gene expression profile similar to adult ciliary ganglion [18] and the absence of the in-situ component are consistent with this cell of origin. [7].

Beyond its rarity, NUT midline carcinoma may initially and transiently respond to several cytotoxics [2] used to treat undifferentiated carcinomas, making even less likely the raising of the right diagnostic suspicion. Regardless the chosen treatment, activity was at most transient and short–lasting [2]. Therefore, to reach the correct diagnosis in the shortest possible time is crucial because prognosis is dismal, clinical conditions may worsen in few days, conventional chemotherapy is only marginally active and, finally, a new target therapy based on bromodomain inhibitors is showing promising results [4, 19, 20]. Despite being an experimental treatment, patients should be strongly encouraged to enroll in clinical trials to rapidly explore these innovative therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, to avoid misleading diagnostic interpretation in case of alpha–fetoprotein elevation, sharing patient information between pathologists and clinicians assessing patients affected by poorly differentiated carcinoma arising nearby midline structures is crucial and we point out to consider NUT midline carcinoma in the differential diagnosis. Finally, in light of our observation, we also suggest to measure alpha–fetoprotein levels during tumor treatment to monitor disease course.

Acknowledgements

All authors wish to thank the patient and his family for their courage in fighting against this extremely aggressive disease. The authors also thank Joan C. Leonard for language editing.

Funding

This work was in part supported by the “Fondazione per la ricerca sui tumori dell’apparato muscoloscheletrico e rari Onlus” (CRT RF = 2016–0917 to G.G.) and by the “Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro” (IG 2015 Id.17226 to G.G.).

Study funders had no role in data collection and interpretation, writing of the report, nor the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

LD, EP, FCS, MA, and GG took care of the patient; MM took care of the patient and required pathological consultations; GP and AF performed the pathological diagnosis; LD, GP, and GG wrote the manuscript on behalf of all authors; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed for publication. The corresponding author (GG) has final responsibility to submit for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The authors obtained written informed consent from the patient to publish information on his disease and clinical course.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is not applicable for this manuscript. The authors obtained patient’s written consent to participate.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ALK

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- beta-HCG

Human chorionic gonadotropin

- BRD

Bromodomain-containing protein

- EMA

Epithelial membrane antigen

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GCT

Germ-cell tumor

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NUT

Nuclear protein in testis

- PLAP

Placental alkaline phosphatase

- TTF-1

Thyroid transcription factor-1

Contributor Information

Lorenzo D’Ambrosio, Email: lorenzo.dambrosio@ircc.it.

Erica Palesandro, Email: erica.palesandro@ircc.it.

Marina Moretti, Email: moretti.marina88@gmail.com.

Giuseppe Pelosi, Email: giuseppe.pelosi@istitutotumori.mi.it.

Alessandra Fabbri, Email: alessandra.fabbri@istitutotumori.mi.it.

Fabrizio Carnevale Schianca, Email: fabrizio.carnevale@ircc.it.

Massimo Aglietta, Email: massimo.aglietta@ircc.it.

Giovanni Grignani, Phone: +39 011 9933623, Email: giovanni.grignani@ircc.it.

References

- 1.French CA, Rahman S, Walsh EM, Kühnle S, Grayson AR, Lemieux ME, Grunfeld N, Rubin BP, Antonescu CR, Zhang S, et al. NSD3-NUT fusion oncoprotein in NUT midline carcinoma: implications for a novel oncogenic mechanism. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(8):928–941. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer DE, Mitchell CM, Strait KM, Lathan CS, Stelow EB, Lüer SC, Muhammed S, Evans AG, Sholl LM, Rosai J, et al. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of NUT midline carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5773–5779. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French C. NUT midline carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(3):149–150. doi: 10.1038/nrc3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, Kastritis E, Gilpatrick T, Paranal RM, Qi J, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146(6):904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills AF, Lanfranchi M, Wein RO, Mukand-Cerro I, Pilichowska M, Cowan J, Bedi H. NUT midline carcinoma: a case report with a novel translocation and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8(2):182–186. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0479-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shatavi S, Fawole A, Haberichter K, Jaiyesimi I, French C. Nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma with a novel three-way translocation (4;15;19)(q13;q14;p13.1) Pathology. 2016;48(6):620–623. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French CA. Demystified molecular pathology of NUT midline carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(6):492–496. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.052902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA. WHO classification of Tumours: pathology and genetics of Tumours of the urinary system and Male genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haack H, Johnson LA, Fry CJ, Crosby K, Polakiewicz RD, Stelow EB, Hong SM, Schwartz BE, Cameron MJ, Rubin MA, et al. Diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma using a NUT-specific monoclonal antibody. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(7):984–991. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318198d666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French CA. The importance of diagnosing NUT midline carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(1):11–16. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang W, French CA, Cameron MJ, Han Y, Liu H. Clinicopathological significance of NUT rearrangements in poorly differentiated malignant tumors of the upper respiratory tract. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013;21(2):102–110. doi: 10.1177/1066896912451651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO classification of Tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harada Y, Koyama T, Takeuchi K, Shoji K, Hoshi K, Oyama Y. NUT midline carcinoma mimicking a germ cell tumor: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):895. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2944-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ball A, Bromley A, Glaze S, French CA, Ghatage P, Köbel M. A rare case of NUT midline carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2012;3:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gynor.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh SA, French CA, Costello BA, Marks RS, Dronca RS, Nerby CL, Roden AC, Peddareddigari VG, Hilton J, Shapiro GI, et al. NUT midline carcinoma: an aggressive intrathoracic neoplasm. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(10):1335–1338. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182a00f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raza A, Cao H, Conrad R, Cobb C, Castelino-Prabhu S, Mirshahidi S, Shiraz P, Mirshahidi HR. Nuclear protein in testis midline carcinoma with unusual elevation of α-fetoprotein and synaptophysin positivity: a case report and review of the literature. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2015;15(10):1199–1213. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2015.1082909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu B, Laskin W, Chen Y, French CA, Cameron MJ, Nayar R, Lin X. NUT midline carcinoma: a neoplasm with diagnostic challenges in cytology. Cytopathology. 2011;22(6):414–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2010.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BioGPS, http://biogps.org/. Accessed 1 Feb 2017.

- 19.Coudé MM, Braun T, Berrou J, Dupont M, Bertrand S, Masse A, Raffoux E, Itzykson R, Delord M, Riveiro ME, et al. BET inhibitor OTX015 targets BRD2 and BRD4 and decreases c-MYC in acute leukemia cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17698–17712. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stathis A, Zucca E, Bekradda M, Gomez-Roca C, Delord JP, de La Motte RT, Uro-Coste E, de Braud F, Pelosi G, French CA. Clinical response of carcinomas harboring the BRD4-NUT Oncoprotein to the targeted Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015/MK-8628. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(5):492–500. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.