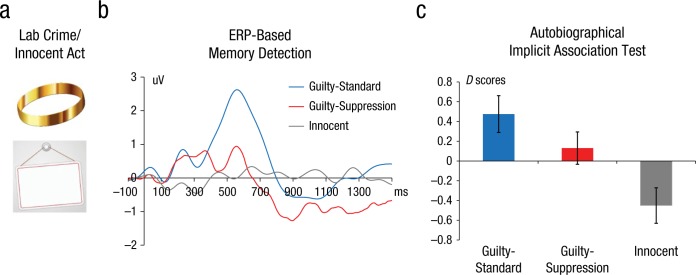

Fig. 2.

Results from Hu, Bergström, Bodenhausen, and Rosenfeld (2015) revealing the effects of suppressing unwanted autobiographical memories. “Guilty” participants enacted a lab crime in which they took a ring from a professor’s mailbox, whereas “innocent” participants wrote their initials on a board (a). Event-related potential (ERP) difference waves (ERP for crime-relevant stimulus—“ring”—minus the average ERP for crime-irrelevant stimuli—e.g., “wallet,” “bracelet”) revealed effects of retrieval suppression on autobiographical memory (b). A classic guilty-knowledge effect was evident among guilty participants without suppression instructions (guilty-standard group), as shown by enhanced retrieval-related ERP positivity during the 300- to 800-ms poststimulus window (for a recent review, see Rosenfeld, Hu, Labkovsky, Meixner, & Winograd, 2013). However, retrieval suppression largely attenuated this ERP positivity while enhancing the subsequent late posterior negativity (800–1,300 ms). Thus, individual guilty-suppression participants could be accurately detected when both ERP components were combined in a peak-to-peak manner. In an autobiographical Implicit Association Test (aIAT), compared to guilty-standard participants, guilty-suppression participants showed a significantly weaker implicit expression of their autobiographical memory (c). D scores reflected the strength of automatic activation of criminal memories and its unintentional influence on participants’ behavior (for rationales behind the aIAT and D scores, see Sartori, Agosta, Zogmaister, Ferrara, & Castiello, 2008). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.