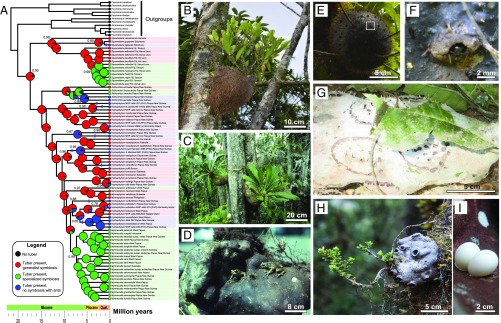

Fig. 1.

The evolution of mutualistic strategies in the Hydnophytinae. (A) Ancestral state reconstruction of mutualistic strategies from 1,000 simulations of character states on a dated phylogeny and a reverse-jump MCMC approach on 1,000 trees (probability shown at key nodes) with 75% of all Hydnophytinae. (B–D) Examples of the three mutualistic strategies. (B) Squamellaria wilkinsonii [G. Chomicki, J. Aroles, A. Naikatini 45 (M)], a generalist ant-plant from Fiji. (C) Myrmecodia alata, a specialized ant-plant from Indonesian Papua. (D) Hydnophytum myrtifolium [M.H.P. Jebb 322 (K)], a species from the highlands of Papua New Guinea that is not associated with ants, but instead accumulates rainwater where the frog, Cophixalus riparius, breeds. (D–I) Diversity of entrance holes in Hydnophytinae. (D) Frog-inhabited Hydnophytum myrtifolium, Papua New Guinea. (E and F) Squamellaria wilsonii, Taveuni, Fiji, with tiny entrance holes fitting the size of the ant partner, Philidris nagasau. (F) Detail of one entrance hole shown in E. (G) Specialized ant-plant, Myrmecodia tuberosa (form “versteegii” sensu Huxley and Jebb, 1993), Papua New Guinea. (H) Hydnophytum spec. nov. [same as Lam 1969 (L)], Papua New Guinea. (I) Eggs of Lepidodactylus buleli, a gecko endemic from Espiritu Santo Island, Vanuatu, inside a Squamellaria vanuatuensis domatium. Photographic credits: (B, E, and F): G. Chomicki; (C and D): M.H.P. Jebb; (G): M. Janda, (H): U. Bauer; (I): J. Orivel. SI Appendix, Fig. S1, gives statistical support.