Significance

Identification of miRNA targets is necessary for understanding their functions; however, current approaches to screening for specific targets are inadequate. For example, most miRNA target-prediction tools only match the 3′-UTR sequence with the miRNA sequence. We created a screening system for miRNA targets using a reporter library of 4,891 full-length cDNAs inserted into the 3′ UTR of a luciferase gene. Using this system, we identified targets of tumor suppressor miR-34a. Among the identified targets, GFRA3, which is crucial for growth of breast cancer cells and affects the survival of patients with breast cancer, was directly regulated by miR-34a via the coding region. Our study shows the advantage of this full-length reporter library system in identifying functional targets of miRNAs.

Keywords: microRNA target screening, miR-34a, reporter library system, breast cancer

Abstract

miRNAs play critical roles in various biological processes by targeting specific mRNAs. Current approaches to identifying miRNA targets are insufficient for elucidation of a miRNA regulatory network. Here, we created a cell-based screening system using a luciferase reporter library composed of 4,891 full-length cDNAs, each of which was integrated into the 3′ UTR of a luciferase gene. Using this reporter library system, we conducted a screening for targets of miR-34a, a tumor-suppressor miRNA. We identified both previously characterized and previously uncharacterized targets. miR-34a overexpression in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells repressed the expression of these previously unrecognized targets. Among these targets, GFRA3 is crucial for MDA-MB-231 cell growth, and its expression correlated with the overall survival of patients with breast cancer. Furthermore, GFRA3 was found to be directly regulated by miR-34a via its coding region. These data show that this system is useful for elucidating miRNA functions and networks.

MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that repress their target genes at the posttranscriptional level by binding as part of the RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex) to regions usually within the 3′ UTR of the target mRNAs. Identifying the targets of miRNAs is critical for understanding their function; however, the current methods used to analyze specific targets in intact cells are not adequate.

Identification of miRNA targets often involves a combination of the following approaches: transcriptome analysis, in silico prediction tools, transcriptome-wide miRNA–mRNA interaction analysis, and cell-based screening systems. Transcriptome analysis, such as microarray or high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) with or without specific miRNAs, may find putative target transcripts whose stability is significantly decreased by the miRNA. However, the targets of the miRNA, which are regulated at the level of translation, may not always correspond to the protein levels (1–3). Current computational tools for prediction of miRNA targets such as TargetScan (4) predict target candidates by miRNA–mRNA sequence matches; however, these candidates have many false positives, and most information regarding the target regions from these prediction tools is restricted to the mRNA’s 3′ UTR. Transcriptome-wide miRNA–mRNA interaction analysis, including RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation-sequencing (RIP-seq) (5, 6) and high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by cross-linking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) (7–10) using the Argonaute (Ago) protein, which is a major RISC component, enables global mapping of Ago-binding sequences. Sequencing of target transcripts captured by biotinylated miRNA mimics also has been reported (11). However, the transcripts detected by these methods are not always functional targets. Finally, cell-based screening systems also have been reported. 3′LIFE, reported by Wolter et al., is a screening system for functional miRNA targets and is based on a luciferase reporter library of 275 human 3′ UTRs; this system sensitively identified the targets of let-7c and miR-10b (12, 13). Recently, the same group reported a reporter library of a larger scale. They constructed a luciferase reporter library of 1,461 human 3′ UTRs, termed the “human 3′UTRome v1 clone collection” (h3′UTRome v1), which consists of human 3′ UTRs from transcription factors, kinases, and RNA-binding proteins (14). This system allows screening individual miRNAs without biasing the screen toward candidate genes identified bioinformatically, enabling the identification of genes targeted via noncanonical and poorly conserved interactions. On the other hand, the 3′-UTR library is not sufficiently large-scale, and the target region is restricted to the 3′ UTR.

To overcome this problem, we developed a luciferase assay-based target screening system. Using cDNAs from the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC) plasmids and the Gateway recombination system, we constructed a reporter plasmid library in which the luciferase gene includes 4,891 nonbiased cDNA sequences in the 3′ UTR. Screening for miRNA targets was conducted by luciferase assays on the reporter library with or without an expression vector for the miRNA of interest. This system allows us to evaluate the putative direct targets of specific miRNAs functionally through its full-length sequence not only at the mRNA level but also at the protein level.

To verify this system, we focused on miR-34a and conducted a screening for its targets. miR-34a is a downstream miRNA of the tumor suppressor p53 (15–17). Decreased expression of miR-34a has been reported in various cancers (18–20), and miR-34a plays a critical role in cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence, and inhibition of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (15, 16, 21–24), indicating that miR-34a is a crucial target of p53 because of its tumor-suppressor function. Although this p53–miR-34a axis is widely known, the above-mentioned potential functions of miR-34a are not fully explained by our limited information regarding the downstream molecular network of miR-34a. Our successful application of the newly created reporter library screening assay systematically identified functional targets of miR-34a without a bias. In addition, our results showed that GFRA3, one of the newly identified targets of miR-34a, regulates the growth of breast cancer cells, and miR-34a regulates it directly via its coding region. These results suggest that this library system can be an important alternative and complementary approach to surveying miRNA-dependent molecular networks and functions.

Results

Construction of the Reporter Library.

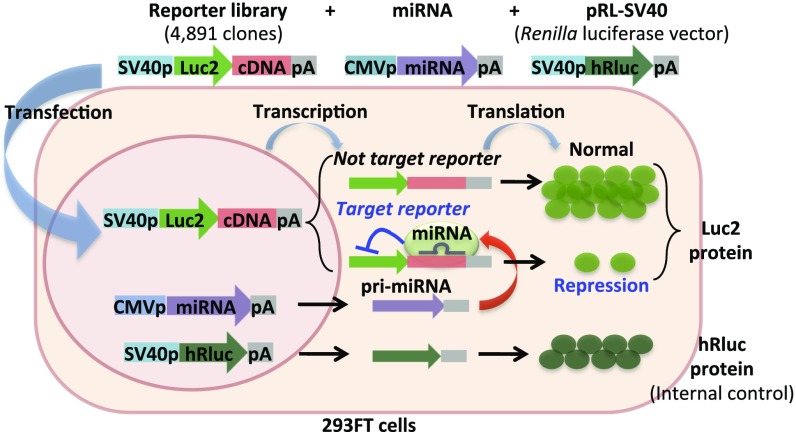

To develop the screening system for identifying the targets of miRNAs, we created a reporter plasmid library. This reporter vector library, which consisted of 4,891 full-length cDNAs in the 3′ UTR of the luc2 gene, was constructed by BP Clonase recombination of pLuc2-KAP-ccdB (Fig. S1 A and C) and the MGC library (Fig. S2) or by inserting a PCR-amplified cDNA into the multiple cloning site of pLuc2-KAP-MCS (Fig. S1B). Cloned cDNAs ranged in size from 290 to 8,472 bp, with an average size of 2,154.3 bp (Dataset S1). The size distribution of the cloned reporter library cDNAs is shown in Fig. S3. These plasmids were purified, and the concentrations were measured. They were diluted and dispensed into 384-well plates (Fig. S2) that then were used as assay plates. A miRNA expression vector was cotransfected with the reporter library in the assay plates, and targets were screened by measuring changes in luc2 reporter activity (Fig. 1).

Fig. S1.

Construct maps and sequence. (A) A map of the pLuc2-KAP-ccdB vector. (B) A map of the pLuc2-KAP-MCS vector. (C) Sequence of the pLuc2-KAP-ccdB vector.

Fig. S2.

A schematic diagram of reporter library construction.

Fig. S3.

Size distribution of reporter library cDNAs.

Fig. 1.

A schematic model of the reporter library system for screening of miRNA targets. CMVp, cytomegalovirus promoter; pA, polyA signal; SV40p, simian virus 40 promoter.

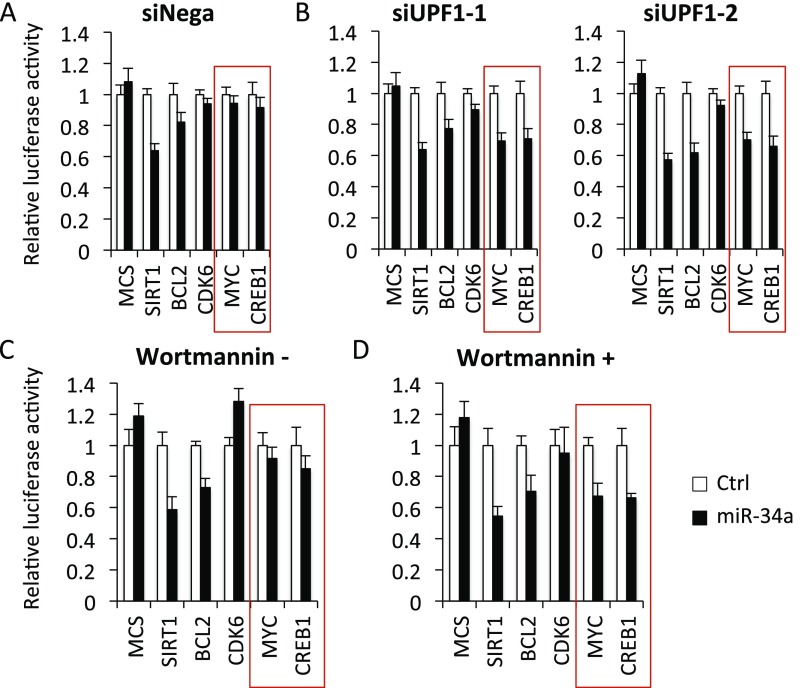

To confirm the functionality of these reporters, we first performed luciferase assays using an expression vector with miR-34a, a transcriptional target miRNA of p53 and a proposed tumor suppressor (25), as well as reporters of its putative targets SIRT1 (Sirtuin 1), BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), CDK6 (cyclin-dependent kinase 6), MYC (v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog), and CREB1 (cAMP-responsive element-binding protein 1) (20, 22, 25–31). However, miR-34a repressed the luciferase activities of only the SIRT1 and BCL2 reporters; the CDK6, MYC, and CREB1 reporter activities were not repressed (Fig. S4 A and C and Tables S1 and S3). We speculated that nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) was the cause. The function of NMD is to reduce errors in gene expression by eliminating mRNA transcripts that contain premature termination codons (PTCs) (Fig. S5) (32, 33). In addition, the length of the 3′ UTR influences the NMD pathway. A number of studies have revealed that artificial 3′ UTRs 800–900 bp in length promote NMD (34–41). The average length of the 3′ UTRs in our reporters is more than 2,000 bp, suggesting that the reporters may be affected by NMD, which would decrease observable changes in the reporter activities under the influence of miRNA. We first performed a luciferase assay using known miR-34a target reporters with two siRNAs for UPF1, the central component of the NMD pathway (33). The luciferase activities of the MYC and CREB1 reporters were decreased by miR-34a when UPF1 was knocked down (red boxes in Fig. S4 A and B and Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, we performed luciferase assays with an NMD inhibitor. SMG1, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase–like kinase, phosphorylates UPF1, and this phosphorylation is crucial for NMD (33). Wortmannin is an inhibitor of the kinase SMG1 and thus inhibits NMD (Fig. S5) (42, 43). The rescue effect seen with the UPF1 knockdown also was detected using wortmannin (Fig. S4 C and D and Table S3). These data suggest that screening of targets of miRNA with an NMD inhibitor can increase assay sensitivity.

Fig. S4.

Preparation of the reporter library system. (A and B) Luciferase assays for the reporters of previously reported miR-34a targets with (B) and without (A) UPF1 knockdown. (C and D) Luciferase assays for the reporters of previously reported miR-34a targets with (D) and without (C) wortmannin, an NMD inhibitor.

Table S1.

Values of luciferase activities in Fig. S4A

| siNega | ||||

| Control | miR-34a | |||

| Reporter | Value | SD | Value | SD |

| MCS | 1 | 0.061 | 1.081 | 0.087 |

| SIRT1 | 1 | 0.037 | 0.640 | 0.044 |

| BCL2 | 1 | 0.070 | 0.823 | 0.062 |

| CDK6 | 1 | 0.031 | 0.940 | 0.034 |

| MYC | 1 | 0.048 | 0.943 | 0.050 |

| CREB1 | 1 | 0.078 | 0.917 | 0.066 |

Table S3.

Values of luciferase activities in Fig. S4 C and D

| Without wortmannin | With wortmannin | |||||||

| Control | miR-34a | Control | miR-34a | |||||

| Reporter | Fold | SD | Fold | SD | Fold | SD | Fold | SD |

| MCS | 1 | 0.102 | 1.190 | 0.080 | 1 | 0.120 | 1.177 | 0.104 |

| SIRT1 | 1 | 0.086 | 0.587 | 0.082 | 1 | 0.108 | 0.546 | 0.062 |

| BCL2 | 1 | 0.027 | 0.728 | 0.060 | 1 | 0.061 | 0.705 | 0.104 |

| CDK6 | 1 | 0.049 | 1.282 | 0.083 | 1 | 0.101 | 0.950 | 0.168 |

| MYC | 1 | 0.083 | 0.916 | 0.073 | 1 | 0.051 | 0.675 | 0.081 |

| CREB1 | 1 | 0.117 | 0.849 | 0.085 | 1 | 0.108 | 0.662 | 0.028 |

Fig. S5.

An overview of NMD and the mechanism of NMD inhibition by wortmannin. PTCs are detected by the complex of UPF1, eRF1/3, and SMG1, known as the “surveillance complex” (SURF), and PTC-containing mRNAs are degraded. Wortmannin inhibits SMG1 phosphorylation of UPF1 and thereby inhibits NMD.

Table S2.

Values of luciferase activities in Fig. S4B

| siUPF1-1 | siUPF1-2 | |||||||

| Control | miR-34a | Control | miR-34a | |||||

| Reporter | Value | SD | Value | SD | Value | SD | Value | SD |

| MCS | 1 | 0.058 | 1.047 | 0.050 | 1 | 0.050 | 1.127 | 0.043 |

| SIRT1 | 1 | 0.044 | 0.640 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.033 | 0.572 | 0.039 |

| BCL2 | 1 | 0.095 | 0.773 | 0.053 | 1 | 0.057 | 0.618 | 0.039 |

| CDK6 | 1 | 0.027 | 0.894 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.038 | 0.922 | 0.048 |

| MYC | 1 | 0.054 | 0.695 | 0.020 | 1 | 0.075 | 0.701 | 0.046 |

| CREB1 | 1 | 0.042 | 0.709 | 0.023 | 1 | 0.094 | 0.661 | 0.030 |

A Cell-Based Screening System Using the Reporter Library-Identified miRNA Targets.

To evaluate the reporter library system with the NMD inhibitor wortmannin, we conducted a screening for potential targets of miR-34a. The screening procedure is shown in Fig. 2A. As a result, we identified eight reported miR-34a targets (SIRT1, SEMA4B, BCL2, MYB, CREB1, CSF1R, MYC, and REF1) (20, 44–48) and four previously unreported miR-34a targets (FAM76A, GFRA3, CARKL, and REM2) (Fig. 2B). Reporters of FAM76A (family with sequence similarity 76, member A) and GFRA3 (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 3) were significantly inhibited by miR-34a (Fig. 2B). We next searched for miR-34a target sites in these identified transcripts using TargetScan, a miRNA target prediction tool (www.targetscan.org/vert_71/) (4). BCL2, CSF1R, SEMA4B, LEF1, and FAM76A have conserved miR-34a target sites, whereas SIRT1, MYB, CREB1, and GFRA3 have poorly conserved miR-34a target sites in their 3′ UTRs (Fig. S6). Other target candidates (MYC, CARKL, and REM2) did not have TargetScan-predicted miR-34a target sites, suggesting that this reporter system may identify miRNA targets not found by miRNA target-prediction tools. In addition, we investigated the expression of these previously unidentified target candidates in miR-34a–overexpressing MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. The mRNA levels of FAM76A and GFRA3 were repressed by the overexpression of a miR-34a mimic in MDA-MB-231 cells, but mRNA levels of CARKL and REM2 were not significantly changed compared with the negative control (Fig. 2C). In addition, the mRNA expression of SEMA4B, CREB1, and MYC was not reduced by miR-34a overexpression, although other identified targets (SIRT1, BCL2, MYB, CSF1R, and LEF1) were down-regulated (Fig. S7). However, protein levels of FAM76A, GFRA3, CARKL, and REM2 were reduced in miR-34a–overexpressing MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2 D and E). These data indicate that miR-34a regulates the expression of these four target candidates and suggest that this system can identify the targets of the miRNA that are regulated at the level of translation. We next carried out luciferase assays with fragmented reporters. Although the reporters of FAM76A and REM2 were regulated by miR-34a via their 3′ UTR, the reporters of GFRA3 and CARKL were regulated via their coding region (Fig. 2F), highlighting the significance of reporters containing whole-length cDNA sequences. Our system identified 12 targets of miR-34a, and two of these targets (16.7%) were regulated by miR-34a via their coding region.

Fig. 2.

The reporter library system identified targets of miR-34a. (A) The screening process. Initially, a screening in 384-well plates with 4,891 reporters was performed, and the top 70 genes were selected. Second, 384-well plate luciferase assays were carried out in triplicate, and 22 genes with reproducible results were selected. Third, 96-well plate luciferase assays were conducted in duplicate four times independently, and 12 targets were identified. (B) Luciferase assays of various reporters in 293FT cells transfected with pcDNA-miR-34a (miR-34a) or the empty vector (Ctrl). 3U, 3′ UTR; MCS, pLuc2-KAP-MCS (empty reporter). Error bars show SD; n = 8. (C) Relative mRNA expression of FAM76A, GFRA3, CARKL, and REM2 in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the negative control miRNA mimic (Ctrl) or miR-34a mimic. (D and E) Western blots (D) and quantification (E) of protein expression of FAM76A, GFRA3, CARKL, REM2, and β-actin in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the negative control miRNA mimic (Ctrl) or miR-34a mimic. (F) Luciferase assays of whole and fragmented reporters in 293FT cells transfected with pcDNA-miR-34a (miR-34a) or empty vector (Ctrl). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. S6.

A Venn diagram comparing the miR-34a target genes predicted by TargetScan and the targets that we identified. White text indicates newly identified targets.

Fig. S7.

Relative mRNA levels of previously identified target genes in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the negative control miRNA mimic (Ctrl) or a miR-34a mimic. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Furthermore, we used our system for screening with miR-146a, a miRNA crucial for inflammation, and identified six previously unreported miR-146a target candidates (RABL2B, CABLES1, TSCOT, BMP5, TM4SF19, and ABHD5) as well as the previously reported targets TRAF6, IRAK1, and CXCR4 (Fig. S8), suggesting that the reporter library system is useful for screening the targets of various miRNAs.

Fig. S8.

Screening for miR-146a targets using the reporter library system. (A) A schematic model of the reporter library system for screening for miR-146a targets. (B) The process of screening for a miR-146a target. (C) Luciferase assays of various reporters in 293FT cells transfected with pcDNA-miR-146a (miR-146a) or the empty vector (Ctrl). MCS, pLuc2-KAP-MCS (empty reporter). Error bars show SD; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n = 6.

GFRA3 Was Directly Regulated by miR-34a via Its Coding Region.

To determine whether these identified targets were directly regulated by miR-34a, we focused on FAM76A and GFRA3, whose reporters were significantly down-regulated by miR-34a, and performed a reporter assay using various fragmented and point-mutated reporters. Reporters for the 3′ UTRs and for the whole inserted cDNAs of FAM76A were repressed by miR-34a (Figs. 2F and 3 A and B), and the repression of the reporter activity of the 3′ UTR FAM76A reporter by miR-34a was reversed when its predicted target sites were mutated (Fig. 3 A and B). These data indicate that FAM76A was directly regulated by miR-34a via its 3′ UTR. In contrast, the activity of the GFRA3 reporter including only the coding region was repressed by miR-34a induction (Fig. 2F). To test whether GFRA3 was directly regulated by miR-34a in its coding region, target candidate sites of miR-34a in the GFRA3 coding region were searched. As a result, three sites that are perfectly consistent with the complementary seed sequence of miR-34a were found in the GFRA3 coding region (Fig. 3C). Of note, these sequences were present in each of the three GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor) domains and located near this domain (between α-helix 2 and α-helix 3) (Fig. S9). Reporter assays using a GFRA3 coding-region reporter with point mutations without amino acid sequence changes in the miR-34a target candidate sites revealed that these three sites were direct target sequences of miR-34a (Fig. 3D). In addition, Western blot analysis using expression vectors of FLAG-tagged GFRA3 with or without point mutations in target sequences showed that FLAG-GFRA3 was repressed by miR-34a, but the repression by miR-34a was reversed in mutated FLAG-GFRA3 (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, we performed AGO2-CLIP analysis in miR-34a mimic-overexpressing or negative control miRNA mimic-overexpressing MDA-MB-231 cells. Target mRNA sequences of FAM76A and GFRA3 were more concentrated in AGO2-binding mRNAs when miR-34a was overexpressed (Fig. S10), indicating that miR-34a directly binds FAM76A and GFRA3 mRNAs. These data indicate that miR-34a directly regulates GFRA3 expression via these three target sequences in its coding region.

Fig. 3.

FAM76A and GFRA3 are directly regulated by miR-34a. (A) The five FAM76A reporters tested in the luciferase assay. 3U, 3′ UTR; mut, sequences with a point mutation; WT, wild-type sequences. (B) Luciferase assays of various FAM76A reporters in 293FT cells transfected with pcDNA-miR-34a or the empty vector. (C) Sequences of the three candidate sites (sites 1–3) for miR-34a targets in the GFRA3 coding region. Sequences with a point mutation in the target candidate sites are shown below. (D) Luciferase assays of various GFRA3-CDS reporters in 293FT cells transfected with pcDNA-miR-34a or the empty vector. ns, not significant. (E) Western blot analysis of wild-type FLAG-GFRA3 [F-GFRA3 (Wt)] or FLAG-GFRA3-mut [F-GFRA3 (Mut1/2/3)] in 293FT cells cotransfection with pcDNA-miR-34a (miR34a) or the empty vector. ***P < 0.001.

Fig. S9.

Target sites of miR-34a in the three GDNF domains in GFRA3. Red text indicates a target site of miR-34a; black rectangles indicate the α-helix; yellow highlighting indicates a redundant amino acid sequence of the GDNF domain.

Fig. S10.

CLIP-qPCR analysis (with an anti-AGO2 antibody) of target sequences of FAM76A and GFRA3 in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing miR-34a or miRNA-negative control mimic. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

GFRA3 Regulates the Growth of MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells.

miR-34a, which is a known tumor suppressor, represses the growth of tumor cells, including breast cancer cells. To test whether these newly identified targets are important for the function of miR-34a, we analyzed the impact of the knockdown of target genes on the growth of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. The knockdown of FAM76A and GFRA3 was successfully implemented using two independent siRNAs of each gene (Fig. S11). A cell-viability assay using the RealTime-Glo MT Cell Viability Assay (Promega) in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the miR-34a mimic indicated that cell viability was reduced by overexpression of the miR-34a mimic, as previously reported (Fig. 4A) (19). Cell viability was reduced in MDA-MB-231 cells in which the activity of GFRA3 was reduced by two siRNAs (Fig. 4A). In addition, the knockdown of GFRA3, but not FAM76A, led to a significant decrease in the ability of MDA-MB-231 cells to form colonies (Fig. 4 B and C). These data show that although FAM76A is not necessary for the growth of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, GFRA3 is an important target of miR-34a function in tumor growth suppression.

Fig. S11.

Real-time PCR analysis of FAM76A and GFRA3 in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with siRNA negative control (siNega) or siRNA targeting these genes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 4.

GFRA3 regulates the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) A cell-viability assay of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miRNA mimics or siRNAs using the MT Cell Viability assay. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with miRNA mimics or siRNAs, cultured for 2 wk, and then stained with crystal violet. (C) Colony numbers were determined by counting the crystal violet-stained cells. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Expression Analysis of GFRA3 and miR-34a in Breast Cancer.

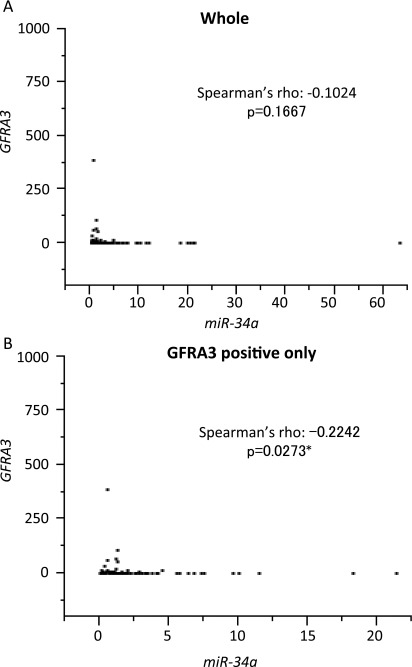

We found that GFRA3, a direct target of miR-34a, regulates the growth of breast cancer cells. A recent study showed that GFRA3 expression is significantly associated with survival in patients with breast cancer (49). In addition, miR-34a expression negatively correlates with tumor grades and stages (19). These results suggest that GFRA3 expression negatively correlates with miR-34a expression in breast cancer. Initially, we analyzed the expression of GFRA3 in breast cancer tissues and found that GFRA3 expression correlated with the overall survival (OS) of breast cancer patients (Fig. 5A). Next, we analyzed the relation between miR-34a and GFRA3 expression. The expression of GFRA3 tended to be higher in breast cancer tissues with weaker miR-34a expression than in tissues with stronger miR-34a expression (Fig. 5B). In addition, we analyzed the relation between expression levels of miR-34a and GFRA3 mRNA only in GFRA3+ breast cancer tissues. The GFRA3 expression levels were found to have a significant negative correlation with miR-34a expression according to Spearman’s rank correlation test (Spearman’s ρ −0.2242, P = 0.0273), although overall samples did not correlate (Spearman’s ρ −0.1024, P = 0.1667) (Fig. S12). These data suggest that the targeting of GFRA3 by miR-34a is an important component of its tumor-suppressor function.

Fig. 5.

Expression of GFRA3 in breast cancer. (A) Kaplan–Meier analysis of the effect of GFRA3 expression on OS among breast cancer patients. (B) The average expression levels of GFRA3 in four groups of breast cancer sorted by miR-34a expression level.

Fig. S12.

The expression of GFRA3 and miR-34a in breast cancer tissue samples. The relation between expression levels of miR-34a and GFRA3 in all (A) and GFRA3+ (B) breast cancer tissue samples.

Discussion

We constructed a reporter plasmid library that includes 4,891 cDNAs in the 3′-UTR region of a luciferase gene and used this library to screen for targets of a miRNA. By means of this system, we identified three previously unidentified target genes of miR-34a.

Generally, two major miRNA-dependent regulatory mechanisms repress target mRNA expression: induction of mRNA instability or inhibition of the translation of protein from mRNA. To identify miRNA target mRNAs that are regulated by mRNA instability, transcriptome analysis in loss- or gain-of-function experiments combined with other approaches such as in silico prediction tools or genome-wide direct interaction analysis by pull-down methods are useful; however, the targets of miRNA that are regulated at the translational level are difficult to survey. Our data indicate that CARKL and REM2 expression levels were decreased at the protein level by induction of a miR-34a mimic in MDA-MB-231 cells but were not reduced at the mRNA level (Fig. 2 C–E). In addition, miR-146a, which is induced by NFκB and acts as a negative feedback regulator of the innate immune response by targeting two adapter proteins, TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6) and IRAK1 (IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1) (50), regulates its targets mainly at the level of translation. The protein levels of TRAF6 and IRAK1 are markedly increased in miR-146a–knockout macrophages compared with wild-type macrophages, but the expression of TRAF6 and IRAK1 genes is not affected at the mRNA level (51). These data indicate that our system is useful for the identification of miRNA targets not only at the mRNA stability level but also at the translation level.

We established that GFRA3 is directly regulated by miR-34a via binding in its coding region. miRNA target-prediction tools such as TargetScan search for sequence matches between miRNA seed sequences and 3′-UTR sequences. Here, we identified a target that did not match any target prediction algorithms.

Although it is believed that miRNAs mostly recognize the 3′ UTR of targeted mRNAs, a recent unbiased study on the identification of target regions of mRNAs at the transcriptome level (by CLIP analysis) revealed that the coding region of mRNA could be targeted physically by a miRNA-containing RISC complex (7–9, 52). In this regard, several miRNAs have been shown to regulate target mRNAs via their coding regions (53–56). In these reports, miRNA-dependent regulation via a coding region has been proved by endogenous expression changes caused by miRNA and a reporter assay using a reporter with a point mutation. We also tested to confirm the regulation of GFRA3 by miR-34a via its coding region by endogenous expression changes caused by miR-34a overexpression and luciferase assays using GFRA3-CDS reporters with point mutations for miR-34a targeting sites in this study. In addition, we found that target mRNA sequences of GFRA3 were more concentrated in AGO2-binding mRNAs when miR-34a was overexpressed, indicating that miR-34a directly binds GFRA3 mRNAs (Fig. S10). These data strongly indicate the coding region-mediated direct regulation of GFRA3 by miR-34a. In addition, transcriptome-wide mRNA–miRNA mapping analyses, such as AGO-CLIP, revealed that the largest proportion (20–50%) of clusters is present in both 3′ UTRs and coding regions (7–9, 52), suggesting that miRNA targets that are regulated via their coding sequence (CDS) may abound.

GFRA3 is an artemin receptor, which is a growth factor belonging to the GDNF family (57). The artemin–GFRA3 axis is important for a diverse range of physiological functions including the development and maintenance of various neuronal populations (58), neurite outgrowth (59), and nerve regeneration (60, 61). The artemin–GFRA3 axis is also important for tumor development. GFRA3 expression is significantly associated with the survival outcomes of patients with breast cancer, and coexpression of artemin with GFRA3 produces a synergistic increase in the odds ratio for both relapse-free and OS (49). We showed a significant association between GFRA3 expression and OS in patients with breast cancer (Fig. 5A). In addition, a knockdown of GFRA3 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells inhibited the growth of the cells; similarly, overexpression of miR-34a reduced cell growth (Fig. 4 A–C). These data suggest that the inhibition of breast cancer growth by miR-34a was caused, at least in part, by the down-regulation of GFRA3.

Thus, our screening for the targets of miR-34a using a newly prepared reporter library system revealed functional and systematic direct targets of miR-34a, including GFRA3, whose target region is located in its CDS. We also showed that the newly identified p53→miR-34a→GFRA3 molecular axis has tumor-suppressive functions in breast cancer. These data indicate that the reporter library system is useful for identifying functional targets of miRNAs in various regions in the targets and at various posttranscriptional stages. This method also should be applicable to the search for functional targets of specific RNA-binding proteins. Application of this strategy should accelerate the research into miRNA-dependent biology and pathologies and may uncover new rules of gene-expression regulation at posttranscriptional levels.

Methods

Two hundred samples of breast carcinomas from 2003–2008 for the mRNA assay came from the archive of the Department of Breast and Endocrine Surgery, Nagoya City University Hospital, Nagoya, Japan. Informed consent for the use of these samples had been obtained at the time of the surgical procedure. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences and conformed to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell-based screening for the targets of miRNAs using a reporter library was performed by modifying a previously described method (62). Five microliters of OPTI-MEM containing 0.15 μL of FuGENE HD (Promega), 20 ng of pcDNA-miR-34a, pcDNA-miR-146a, or pcDNA3.1(+), and 5 ng of pRL-SV40 (Promega) Renilla luciferase construct was added to the 384-well reporter library plates and incubated for 20 min. Then 293FT cells (Invitrogen) in 40 μL of DMEM containing 10% of FBS were added into each well using an automated multidispenser ECO DROPPER III (AS ONE). The cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 24 h. Then 5 μL of the culture medium with or without 0.5 nL of 1 mM wortmannin (Sigma) stock solution, which was diluted in DMSO, was added into each well (final concentration 100 nM). The cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 5 h. Luciferase activity was measured by means of an ARVO X3 (PerkinElmer) and the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Overviews of the system and procedure are shown in Fig. 1A and Fig. S13.

Fig. S13.

An overview of the high-throughput screening procedure.

For additional information on methods, SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Constructs.

The pLuc2-KAP-ccdB vector included the chloramphenicol resistance gene and the ccdB gene between the attP1 and attP2 sites in the 3′ UTR of the luc2 reporter gene. The map and sequence of this construct are shown in Fig. S1 A and C. The pLuc2-KAP-MCS reporter was generated by inserting the multiple cloning site of pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen) into pLuc2-KAP-ccdB at the XhoI and XbaI sites. The map of pLuc2-KAP-MCS is shown in Fig. S1B. The pcDNA-miR-34a vector was constructed by inserting the PCR-amplified and EcoRI- and EcoRV-digested human pri-miR-34a sequence at the EcoRI and EcoRV sites of pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen). PCR amplification of the human pri-miR-34a sequence was conducted by means of HEK293T cell genomic DNA as a template and miR-34a forward (5′-TTG AAT TCT GCT GGG GAG AGG CAG GAC A-3′) and reverse (5′-TTG ATA TCG TGG CGC AGA AGA GCT TCC-3′) primers. We constructed 3′-UTR reporters and CDS reporters (Fig. 2F) by ligating PCR-amplified DNAs into the pLuc2-KAP-MCS vector. Mutagenesis experiments on FAM76A reporters and GFRA3-CDS reporters (Fig. 3 A–D) were carried out by inverse PCR of these reporters with phosphorylated primers and ligation of the amplicons. Primer sequences used for the inverse PCR are listed in Table S4. pcDNA-FLAG was constructed by inserting 3×FLAG sequences into the multiple cloning site of pcDNA3.1(+). FLAG-tagged GFRA3 vectors (pcDNA-FLAG-GFRA3 or pcDNA-FLAG-GFRA3-mut) were constructed by inserting PCR-amplified GFRA3 or mutated GFRA3 into pcDNA-FLAG.

Table S4.

Primer sequences for mutagenesis of reporters

| Primer | Sequence |

| FAM76A-3Umut1/2-F | TTTGAAAAGATCTATCTTCAGACTTGG |

| FAM76A-3Umut1/2-R | GTTCAGAGGGTTCGCGAGATATATA |

| FAM76A-3Umut3-F | GATTGATTTTAAATTCTCACTGTCCGACTTC |

| FAM76A-3Umut3-R | ACATAAAACAATCAGGAAAGGGGTGG |

| GFRA3-3Umut-SmaI-F | TTTCCCGGGCTGTCCCCGGATCCTGCCGA |

| GFRA3-3Umut-SmaI-R | TTTCCCGGGGCAGGCAGTAGTTTTCCATCCTC |

| GFRA3-CDSmut1-F | CTTCGGTCCCTGCTGACTGCC |

| GFRA3-CDSmut1-R | GCTCCTCTGAGGGTAAAGGGGTG |

| GFRA3-CDSmut2-F | CCTCAGGCAGCTGCTCACTTTCTTC |

| GFRA3-CDSmut2-R | CAGACGTGGCGCTGACAATGGG |

| GFRA3-CDSmut3-F | GACATCCTAGGAACTTGTGCAACAG |

| GFRA3-CDSmut3-R | CATGGGATGACAATGGGTCTGG |

Reporter Library Construction.

The MGC plasmid library (63) was purchased from ATCC. The construction of the reporter plasmid was conducted using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). Forty nanograms of the MGC plasmid, 30 ng of pLuc2-KAP-ccdB, and 0.4 µL of BP Clonase II (Invitrogen) were incubated at 25 °C overnight and then treated with proteinase K at 37 °C for 10 min. The recombined DNA was transfected into DH5α-competent cells, and the cells were incubated on LB-kanamycin plates. The transformants were cultured in a LB-ampicillin medium, and the plasmids were extracted using the NucleoSpin Multi 96 plus Plasmid Kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL) or LaboPass Mini (Cosmo Genetech). Quality testing of the plasmids was performed by sequencing (80 clones) and restriction enzyme digestion (40 clones). Some reporter vectors were constructed by inserting PCR-amplified cDNA into the multiple cloning sites of pLuc2-KAP-MCS. The reporter library is listed in Dataset S1. Reporter plasmids were diluted to 4 ng/μL in elution buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl; pH 8.5) in 96-well plates and then were dispensed into 384-well culture plates (Greiner) at 5 μL per well using a Multi Dispenser EDR-384SII (Biotec).

Luciferase Assays.

Luciferase assays were performed by incubating 20 μL of OPTI-MEM containing 0.4 μL of FuGENE HD, 25 ng of reporter plasmids, 50 ng of effector plasmids, and 5 ng of pRL-SV40 for 20 min in 96-well culture plates. Then 293FT cells in 100 μL of DMEM containing 10% of FBS were added to each well and cultured for 24–36 h. Then, 20 μL of the culture medium with or without 0.014 μL of a 1-mM wortmannin (Sigma) stock solution was added into each well (final concentration 100 nM) and incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 5 h. For UPF1-knockdown experiments, 3 pmol of siRNAs [siUPF1 (s11927, s11928)] or negative control (AM4611; Ambion, Life Technologies) were transfected with 0.5 μL of RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) after 7 h of transfection of reporters. Luciferase activity was measured using an ARVO X3 (PerkinElmer) and the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Western Blotting.

293FT cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% of FBS. miRNA mimic [miR-34a (MC11030)] or control (4464058; mirVana) (Thermo) or siRNAs [FAM76A (s47147, s57749), GFRA3 (s5718, s5719), or negative control (AM4611); Ambion, Life Technologies] were transfected into MDA-MB-231 cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). After 48 h, total-RNA samples were extracted by means of ISOGEN (Nippon Gene). For Western blot analysis, pcDNA vectors (pcDNA or pcDNA-miR-34a and pcDNA-FLAG-GFRA3 or pcDNA-FLAG-GFRA3-mut) were cotransfected with FuGENE HD into 293FT cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, the cells were washed with PBS and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% DOC, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40]. Proteins in the cell lysates were separated by SDS/PAGE followed by semidry transfer to a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked for 30 min with Blocking One (Nacalai Tesque), incubated with an anti-FAM76A (ab90042; Abcam), anti-GFRA3 (ab8028; Abcam), anti-CARKL (ab69920; Abcam), anti-REM2 (ABD37; Merck Millipore), anti–β-actin (A5316; Sigma), or an anti–FLAG-M2 antibody (Sigma) at 4 °C overnight or at room temperature for 1 h, rinsed, and then incubated for 1 h with ECL mouse IgG HRP-conjugated whole antibody (GE Healthcare). The blot was developed with the ECL Select Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare). The protein levels are normalized to β-actin levels in each sample.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA samples were extracted by means of ISOGEN (Nippon Gene). Reverse transcription then was carried out using random primers (Invitrogen) by means of ReverTra Ace (TOYOBO). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was run using THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The primer sequences used for the real-time PCR are listed in Table S5. The results are expressed as mRNA levels normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression in each sample. To determine mRNA levels, at least three independent RNA samples were analyzed.

Table S5.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR and CLIP

| Primer | Sequence |

| FAM76A F | GGAACGCCCAAACCTTGTCAG |

| FAM76A R | GTGTGCACAGCCAGCACAGC |

| GFRA3 F | CGCATGAAGAACCAGGTTGCC |

| GFRA3 R | GAGGCAGAGGTCTGAGTCTG |

| CARKL F | GAGCTGTTAGCCACCTGGTC |

| CARKL R | GGACTTCAGGAACTCTGGGC |

| REM2 F | GGACACAGAAACCACAGCACTC |

| REM2 R | GACAGGCATACTGCCTCTTCG |

| SIRT1 F | CTGACTTCAGGTCAAGGGATGG |

| SIRT1 R | GAGATGGCTGGAATTGTCCAGG |

| SEMA4B F | GACCCCTACTGTGCTTGGAG |

| SEMA4B R | GGGACACAACCGAAGACGCG |

| BCL2 F | AGAGCGTCAACCGGGAGATG |

| BCL2 R | CAAACAGAGGCCGCATGCTG |

| MYB F | GCAGTGACGAGGATGATGAGG |

| MYB R | CCATTCTGTTCCACCAGCTTCTTC |

| CREB1 F | GGCCGTGAACGAAAGCAGTG |

| CREB1 R | GCAATCTGTGGCTGGGCTTG |

| CSF1R F | GTGCTCAGCCAGCAGCGTTG |

| CSF1R R | TGCTGGCCACGCAGGAGTAG |

| MYC F | GCCCATTTGGGGACACTTCC |

| MYC R | GCACCGAGTCGTAGTCGAGG |

| LEF1 F | GCACAAACCTCTCAGGAGCC |

| LEF1 R | GATGTTCTCGGGATGGGTGG |

| GAPDH F | CCTGGTCACCAGGGCTGC |

| GAPDH R | CGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTGATG |

| FAM76A CLIP-1 F | CCTGCCATACCCATGAGCAAAC |

| FAM76A CLIP-1 R | GCCTCTTCCATTATACCAAGTCTGAAG |

| FAM76A CLIP-2 F | GGGCAGAAAGCAAGGTTGTCC |

| FAM76A CLIP-2 R | GAAGTGGCAGTGTGAGAATTTAAAATCAATC |

| GFRA3 CLIP-1 F | CTGGATTCCTGCACCTCTAGC |

| GFRA3 CLIP-1 R | CTGAGTTGCTGTGCTGCCTC |

| GFRA3 CLIP-2 F | GACAAGTGTGACCGGCTGCG |

| GFRA3 CLIP-2 R | GAAAGTGAGCAGCTGCCTGAG |

| GFRA3 CLIP-3 F | GCTTTGCAGATCACGCCTGG |

| GFRA3 CLIP-3 R | CATCTGGACTGCTCTGTTGCAC |

Cell Growth Analysis.

Cell viability assays were conducted using the RealTime-Glo MT Cell Viability Assay (Promega). Six picomoles of miRNA mimics or siRNAs were transfected into MDA-MB-231 cells (5 × 103 cells per well) with 0.75 μL of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX and 50 μL of OPTI-MEM in 48-well plates. After 72 h, the medium was changed to a growth medium with MT Cell Viability Substrate (Promega) and NanoLuc Enzyme (Promega), and then the cells were cultured for 24 h. Next, luciferase activity was measured using an ARVO X3 (PerkinElmer). For a colony-formation assay, 6 pmol of miRNA mimics or siRNAs was transfected into MDA-MB-231 cells (103 cells per well) with 0.75 μL of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX and 50 μL of OPTI-MEM in a 12-well plate. After 2 wk, cell colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. These experiments were conducted on at least three independent samples.

Ago2-CLIP Analysis.

CLIP was performed as described elsewhere (64), with modifications. Namely, 100 pmol of miR-34a mimic (MC11030; mirVana; Thermo) or negative control mimic (4464058; mirVana; Thermo) was transfected into 15% confluent MDA-MB-231 cells in a 10-cm dish using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). After 60 h, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and UV-irradiated twice at 200 and 400 mJ/cm2 using a UV crosslinker (CL-1000; UVP). The cells were lysed with PXL buffer (1× PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40), and then we added RQ1 DNase (final concentration 30 U/mL; Promega) with incubation for 5 min. After centrifugation, an anti-human AGO2 mouse monoclonal antibody (4G8; Wako)- or normal mouse IgG (Santa Cruz)–Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo) complex was added to the supernatants and incubated on a rotator for 2 h at room temperature. The Dynabeads were washed twice with PXL buffer, high-salt wash buffer (5× PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40), and PNK buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40), followed by proteinase K treatment, phenol–chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. The precipitated RNAs were reverse transcribed with ReverTra Ace (TOYOBO). qRT-PCR was performed using THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The primer sequences used for the CLIP are listed in Table S5.

Clinical Samples and Expression Analysis.

The archive of the Department of Breast and Endocrine Surgery, Nagoya City University Hospital in Japan, had 200 samples of breast carcinomas from 2003–2008 available for an mRNA assay. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after resection and were stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Informed consent was obtained before the surgical procedure. OS was defined as the interval from the date of primary surgery to death from any cause. The median follow-up period was 6.9 y (range 1–135 mo). This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences and conformed to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to measure mRNA expression of GFRA3 and of the housekeeping gene ACTB. qRT-PCR assays were performed on a 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The amplification reaction mixture contained 2 μL of cDNA (1–100 ng), 10 μL of the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 1 μL of TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Buffer, and 7 μL of RNase-free water in a total volume of 20 μL. The PCR conditions used for GFRA3 and ACTB were 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 20 s, and 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 3 s and annealing with elongation at 62 °C for 30 s. The samples were amplified independently in duplicate. The relative concentrations of GFRA3 mRNA were normalized to the ACTB gene as an internal control. The cutoff value of GFRA3 mRNA was the median in this study.

cDNA was reverse-transcribed from total-RNA samples using specific miRNA primers from the TaqMan MicroRNA Assays and reagents from the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). The resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR using TaqMan MicroRNA Assay primers with the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and was analyzed by means of a 7500 ABI PRISM Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as described previously (65). The relative levels of miR-34a expression were calculated from the relevant signals by normalization to the signal of U6B miRNA expression. The name of the assay for miR-34a was “hsa-mir-34a” (Applied Biosystems). To study the relation between expression levels of miR-34a and GFRA3 mRNA, Spearman’s rank correlation test was used.

Survival curves were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and verified by the log-rank test. OS was censored when patients were alive. The level of significance was set to P < 0.05. Statistical calculations were performed in JMP10 software (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Statistical Analysis.

Two-tailed independent Student’s t tests were used to calculate all P values. Asterisks in the figures indicate differences with statistical significance: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Akio Yamashita, Masato Yano, Tomoaki Tanaka, and Kazuhiko Kuwahara for helpful discussions and Mayuko Yoda, Yukinari Osaka, Nobuhiro Yamamoto, and Ayaka Ichise for technical assistance. This work was supported by Core Research for the Evolutionary Science and Technology (CREST) funding from the Japan Science and Technology Agency; CREST funding from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Grants 26113008, 15H02560, 15K15544, 15K15026, and 25860139 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; NIH Grants AR050631 and AR065379; the Naito Foundation; and a Bristol-Myers K.K. RA Clinical Investigation Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1620019114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meijer HA, et al. Translational repression and eIF4A2 activity are critical for microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Science. 2013;340:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1231197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloonan N, et al. Stem cell transcriptome profiling via massive-scale mRNA sequencing. Nat Methods. 2008;5:613–619. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao J, et al. Genome-wide identification of polycomb-associated RNAs by RIP-seq. Mol Cell. 2010;40:939–953. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hafner M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helwak A, Kudla G, Dudnakova T, Tollervey D. Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding. Cell. 2013;153:654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ule J, et al. CLIP identifies Nova-regulated RNA networks in the brain. Science. 2003;302:1212–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1090095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan SM, et al. Sequencing of captive target transcripts identifies the network of regulated genes and functions of primate-specific miR-522. Cell Reports. 2014;8:1225–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolter JM, Kotagama K, Pierre-Bez AC, Firago M, Mangone M. 3'LIFE: A functional assay to detect miRNA targets in high-throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e132. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolter JM, Kotagama K, Babb CS, Mangone M. Detection of miRNA targets in high-throughput using the 3'LIFE assay. J Vis Exp. 2015;(99):e52647. doi: 10.3791/52647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotagama K, Babb CS, Wolter JM, Murphy RP, Mangone M. A human 3'UTR clone collection to study post-transcriptional gene regulation. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1036. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang TC, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, et al. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat Med. 2011;17:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada N, et al. A positive feedback between p53 and miR-34 miRNAs mediates tumor suppression. Genes Dev. 2014;28:438–450. doi: 10.1101/gad.233585.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lodygin D, et al. Inactivation of miR-34a by aberrant CpG methylation in multiple types of cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2591–2600. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu MY, Fu J, Xiao X, Wu J, Wu RC. MiR-34a regulates therapy resistance by targeting HDAC1 and HDAC7 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;354:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rokavec M, Li H, Jiang L, Hermeking H. The p53/miR-34 axis in development and disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014;6:214–230. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bu P, et al. A microRNA miR-34a-regulated bimodal switch targets Notch in colon cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:602–615. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He L, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim NH, et al. A p53/miRNA-34 axis regulates Snail1-dependent cancer cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:417–433. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raver-Shapira N, et al. Transcriptional activation of miR-34a contributes to p53-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen F, Hu SJ. Effect of microRNA-34a in cell cycle, differentiation, and apoptosis: A review. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2012;26:79–86. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tivnan A, et al. MicroRNA-34a is a potent tumor suppressor molecule in vivo in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sotillo E, et al. Myc overexpression brings out unexpected antiapoptotic effects of miR-34a. Oncogene. 2011;30:2587–2594. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christoffersen NR, et al. p53-independent upregulation of miR-34a during oncogene-induced senescence represses MYC. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:236–245. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyota M, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4123–4132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun F, et al. Downregulation of CCND1 and CDK6 by miR-34a induces cell cycle arrest. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1564–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ. miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13421–13426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frischmeyer PA, Dietz HC. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in health and disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1893–1900. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hug N, Longman D, Cáceres JF. Mechanism and regulation of the nonsense-mediated decay pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1483–1495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toma KG, Rebbapragada I, Durand S, Lykke-Andersen J. Identification of elements in human long 3′ UTRs that inhibit nonsense-mediated decay. RNA. 2015;21:887–897. doi: 10.1261/rna.048637.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eberle AB, Stalder L, Mathys H, Orozco RZ, Mühlemann O. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by spatial rearrangement of the 3′ untranslated region. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh G, Rebbapragada I, Lykke-Andersen J. A competition between stimulators and antagonists of Upf complex recruitment governs human nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz-Echevarría MJ, Peltz SW. The RNA binding protein Pub1 modulates the stability of transcripts containing upstream open reading frames. Cell. 2000;101:741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hogg JR, Goff SP. Upf1 senses 3'UTR length to potentiate mRNA decay. Cell. 2010;143:379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang L, et al. RNA homeostasis governed by cell type-specific and branched feedback loops acting on NMD. Mol Cell. 2011;43:950–961. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurt JA, Robertson AD, Burge CB. Global analyses of UPF1 binding and function reveal expanded scope of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genome Res. 2013;23:1636–1650. doi: 10.1101/gr.157354.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yepiskoposyan H, Aeschimann F, Nilsson D, Okoniewski M, Mühlemann O. Autoregulation of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway in human cells. RNA. 2011;17:2108–2118. doi: 10.1261/rna.030247.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pal M, Ishigaki Y, Nagy E, Maquat LE. Evidence that phosphorylation of human Upfl protein varies with intracellular location and is mediated by a wortmannin-sensitive and rapamycin-sensitive PI 3-kinase-related kinase signaling pathway. RNA. 2001;7:5–15. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usuki F, et al. Inhibition of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay rescues the phenotype in Ullrich’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:740–744. doi: 10.1002/ana.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim NH, et al. p53 and microRNA-34 are suppressors of canonical Wnt signaling. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra71. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaller M, et al. Genome-wide characterization of miR-34a induced changes in protein and mRNA expression by a combined pulsed SILAC and microarray analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M111 010462. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernardo BC, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of the miR-34 family attenuates pathological cardiac remodeling and improves heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17615–17620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206432109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Navarro F, et al. miR-34a contributes to megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells independently of p53. Blood. 2009;114:2181–2192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riepsaame J, et al. MicroRNA-mediated down-regulation of M-CSF receptor contributes to maturation of mouse monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Front Immunol. 2013;4:353. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu ZS, et al. Prognostic significance of the expression of GFRα1, GFRα3 and syndecan-3, proteins binding ARTEMIN, in mammary carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boldin MP, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1189–1201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boudreau RL, et al. Transcriptome-wide discovery of microRNA binding sites in human brain. Neuron. 2014;81:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi L, et al. MicroRNA-128 targets myostatin at coding domain sequence to regulate myoblasts in skeletal muscle development. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1895–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang S, et al. MicroRNA-181a modulates gene expression of zinc finger family members by directly targeting their coding regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7211–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hausser J, Syed AP, Bilen B, Zavolan M. Analysis of CDS-located miRNA target sites suggests that they can effectively inhibit translation. Genome Res. 2013;23:604–615. doi: 10.1101/gr.139758.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: Signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baloh RH, et al. Artemin, a novel member of the GDNF ligand family, supports peripheral and central neurons and signals through the GFRalpha3-RET receptor complex. Neuron. 1998;21:1291–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paveliev M, Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. GDNF family ligands activate multiple events during axonal growth in mature sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jankowski MP, Rau KK, Soneji DJ, Anderson CE, Koerber HR. Enhanced artemin/GFRα3 levels regulate mechanically insensitive, heat-sensitive C-fiber recruitment after axotomy and regeneration. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16272–16283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2195-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bennett DL, et al. Artemin has potent neurotrophic actions on injured C-fibres. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:330–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2006.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yokoyama S, et al. A systems approach reveals that the myogenesis genome network is regulated by the transcriptional repressor RP58. Dev Cell. 2009;17:836–848. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Klausner RD, Collins FS. The mammalian gene collection. Science. 1999;286:455–457. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Licatalosi DD, et al. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature. 2008;456:464–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kondo N, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Fujii Y, Yamashita H. miR-206 Expression is down-regulated in estrogen receptor alpha-positive human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5004–5008. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.