Abstract

Purpose

Interaction of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) co-receptor on T cells with the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumor cells can lead to immunosuppression, a key event in the pathogenesis of many tumors. Thus, determining the amount of PD-L1 in tumors by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is important as both a diagnostic aid and a clinical predictor of immunotherapy treatment success. Because IHC reactivity can vary, we developed computational simulation models to accurately predict PD-L1 expression as a complementary assay to affirm IHC reactivity.

Methods

Multiple myeloma (MM) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell lines were modeled as examples of our approach. Non-transformed cell models were first simulated to establish non-tumorigenic control baselines. Cell line genomic aberration profiles, from next-generation sequencing (NGS) information for MM.1S, U266B1, SCC4, SCC15, and SCC25 cell lines, were introduced into the workflow to create cancer cell line-specific simulation models. Percentage changes of PD-L1 expression with respect to control baselines were determined and verified against observed PD-L1 expression by ELISA, IHC, and flow cytometry on the same cells grown in culture.

Result

The observed PD-L1 expression matched the predicted PD-L1 expression for MM.1S, U266B1, SCC4, SCC15, and SCC25 cell lines and clearly demonstrated that cell genomics play an integral role by influencing cell signaling and downstream effects on PD-L1 expression.

Conclusion

This concept can easily be extended to cancer patient cells where an accurate method to predict PD-L1 expression would affirm IHC results and improve its potential as a biomarker and a clinical predictor of treatment success.

Keywords: Computational modeling, Simulation modeling, PD-L1, Multiple myeloma, Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Programmed death-ligand 1(PD-L1) is a member of the B7 family of molecules and is present on the surface of many hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells [1–3]. It is part of the programmed death pathway, binding to the co-receptor programmed death-1 (PD-1) on the surface of activated T cells, natural killer cells, B cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells as one of the checkpoints for normal immune homeostasis [1, 2]. PD-L1 is also found on melanoma cells, renal cell carcinoma cells, multiple myeloma (MM) cells, oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells, gastrointestinal cancer cells, bladder cancer cells, ovarian cancer cells, and hematological cancer cells [4–6]. In cancer pathogenesis, overexpression of PD-L1 by tumor cells increases immunosuppression by inhibiting T cell proliferation, reducing T cell survival, inhibiting cytokine release, and promoting T cell apoptosis [4, 7].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is currently used to detect PD-L1 on tumor cells after biopsy. However, its detection varies depending upon differences in antibody specificities, affinities, and commercial sources [8, 9]. This variability results in challenges using PD-L1 reactivity to select patients for PD-L1 immunotherapy and to predict clinical treatment outcomes. For example, in a study of 1400 patients, ~45 % patients with PD-L1+ tumor cells and ~15 % patients with PD-L1− tumor cells had objective responses [10]. The high proportion of patients with PD-L1− tumor cells that had objective responses argues against the use of IHC as a sole method to determine PD-L1 expression for patient selection for treatment.

Complicating the situation is the presence of soluble PD-L1 (sPD-L1) in serum and plasma [11]. In normal individuals, sPD-L1 concentrations vary with age and range from 725.0 ± 181.0 pg/ml (children 3–10 years of age), 766.0 ± 253.0 pg/ml (young adults), and 889.0 ± 270.0 (adults) to 1040 ± 681.0 pg/ml (older adults 51–70 years of age) [12]. In patients with cancer, sPD-L1 concentrations are elevated and may play an important role in tumor immune evasion and patient prognosis [12]. For example, elevated sPD-L1 concentrations are associated with poor post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma [13], poor prognosis in patients with advanced gastric cancer [14], correlated with differentiation and lymph node metastasis, and associated with diffuse large B cell lymphoma [15]. Patients with elevated sPD-L1 experienced a poorer prognosis with a 3-year overall survival of 76 versus 89 % concluding that sPD-L1 is a potent predicting biomarker in this disease.

There is a critical need to improve methods to accurately affirm PD-L1 expression. Since determining PD-L1 reactivity in tumors using IHC and determining sPD-L1 in serum or plasma can both be variable [15], we created predictive computational simulation models containing cell line genomic signatures to fill this gap and to predict PD-L1 expression with a validated, cancer network model. Simulation models using a computational approach can accurately predict and reproduce the behavior of interacting and interdependent biological systems, like that of signaling pathways in cancer cells. This knowledge is useful in determining the parameters important in the expression of cell-associated immunosuppressive biomarkers. PD-L1 expression is regulated by signaling pathways, transcription factors, and epigenetic factors modulated by tumor genomics [2, 16, 17], which makes PD-L1 an ideal molecule to predict via computational simulation modeling. In this study, we constructed computational simulation models of PD-L1 expression in MM and oral SCC cell lines. We used these models to accurately show that cancer cell genomics play an integral role in influencing cell signaling and downstream effects on PD-L1 expression. We show differences in PD-L1 expression among cell lines, and these results were verified against PD-L1 concentrations detected on the same cells grown in culture using ELISA, IHC, and flow cytometry. Thus, predictions of PD-L1 expression may be a method to affirm diagnostic IHC results and support the role of PD-L1 as a biomarker and clinical predictor of treatment success.

Materials and methods

Cell line mutational profiles

MM and SCC cell line-specific mutational profiles were first created. MM.1S is a peripheral blood B lymphoblast from a 42-year-old adult with immunoglobulin A lambda myeloma [18, 19], and U266B1 is a peripheral blood B lymphocyte from a 53-year-old adult with a plasma cell myeloma [20]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) information containing mutations for MM.1S and U266B1 (Fig. 1a) was taken from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics database [21, 22], the TCGA Research Network (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/), and published information [23–25]. SCC cell lines SCC4 (tongue), SCC15 (tongue), UM-SCC19 (tongue), SCC25 (tongue), UM-SCC84 (tongue), UM-SCC92 (tongue), and UM-SCC99 (tonsil) were also used [25, 26]. NGS information containing mutations (Fig. 1a) and copy number variations (Fig. 1b) was taken from the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics database [21, 22] and the Sanger sites for SCC4 (http://www.cbioportal.org/case.do?sample_id=SCC4_UPPER_AERODIGESTIVE_TRACT&cancer_study_id=cellline_ccle_broad, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cell_lines/sample/overview?id=910904); SCC15 (http://www.cbioportal.org/case.do?sample_id=SCC15_UPPER_AERODIGESTIVE_TRACT&cancer_study_id=cellline_ccle_broad, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cell_lines/sample/overview?id=910911); and SCC25 (http://www.cbioportal.org/case.do?sample_id=SCC25_UPPER_AERODIGESTIVE_TRACT&cancer_study_id=cellline_ccle_broad, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cell_lines/sample/overview?id=910701).

Fig. 1.

Cell line mutations (a) and copy number variations (b) for MM cell lines MM.1S and U266B1 and oral SCC cell lines SCC4, SCC15, and SCC25 that were used to create cancer cell line-specific computational simulation models. Mutations and copy number variations were assessed for changes in gene sequence (c). Mutated genes were identified and first compared to the Cellworks Group, Inc. (CWG) Learnt Mutational Library (c). If the effect of gene mutation on gene function was listed in the CWG Library, then that result was used. If not, the effect of gene mutation on gene function was determined using the cancer mutation effect prediction algorithms FannsDB, SIFT, Polyphen, FATHMM, Mutation Assessor (MA), and PROVEAN. Final results were recorded as an effect of unknown signature, neutral to gene function, or deleterious to gene function

All cell line-specific mutation and copy number variation profiles were assessed for changes in gene sequence that altered gene function (Fig. 1c). Mutated genes were first compared to the Cellworks Group, Inc. Learnt Mutational Library. This is a library of genes whose mutations are known or previously determined to effect gene function. If the mutation was listed in the library, then that result was used. If the mutation was not listed in the library, then the effect of gene mutation on gene function was determined using cancer mutation effect prediction algorithms [27]. These algorithms include SIFT [28], Polyphen [29], FATHMM [27], Mutation Assessor [30], and PROVEAN [31]. Final results were recorded as an effect of unknown signature, neutral to gene function, or deleterious to gene function (Fig. 1c).

Predictive computational simulation models

Computational simulation model creation (Fig. 2a–e), prediction (Fig. 2f), and validation (Fig. 2g, h) for MM cell lines (MM.1S, U266B1) and oral SCC cell lines (SCC4, SCC15, and SCC25) were created in a series of successive steps. Non-transformed cell models (e.g., models not containing cell line-specific mutations and copy number variations) were used that contained integrated cancer cell networks created as previously described [32, 33]. These networks were created from published reports on cell receptors, signaling pathways, pathway signaling intermediates, activation factors, transcription factors, and enzyme kinetics. Information on gene functionality and links between different genes, proteins, and pathways were manually researched, analyzed, curated, and aggregated to construct the integrated network maze. Reactions were modeled mathematically using Michaelis–Menten kinetics, mass action kinetics, and variations of these representations. Modeled events included, but were not limited to interactions at the cell surface (e.g., binding of agonists to receptors, etc.), metabolic and cell signaling pathways (e.g., signal pathway events, cross talk interactions among pathways, feedback control, etc.), activation and regulation of genes (e.g., activation links of transcription factors, etc.), intracellular processes such as proteasomal degradation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, DNA damage and repair pathways, and cell cycle pathways. Time-dependent changes in signaling pathway fluxes of biological reactions were modeled utilizing modified ordinary differential equations solved with a proprietary solver. At this level, data input and output were validated with a series of internal control analysis checks on predictive expression. Analyses included assessing the effects of pathway molecule overexpression or knockdown on predictive pathway responses; effects of drugs on predictive pathway responses; and activation, regulation, and cross talk interactions among pathway intermediates on predictive pathway responses.

Fig. 2.

A schema showing computational simulation model creation (a–e), prediction (f), and validation (g, h) for MM cell lines (MM.1S, U266B1) and oral SCC cell lines (SCC4, SCC15, and SCC25). Cell-specific mutational profiles (a) were determined, and the presence and impact of deleterious gene mutations and copy number variations on gene function were assessed (b). Information was imported into non-transformed predictive computational simulation models (c, d) to create cell line-specific computation models (e). These models were then used to predict PD-L1 expression (f). Predicted PD-L1 expression was verified against observed PD-L1 expression on the same cells grown in culture (g). The match rates between the predicted PD-L1 expression and the experimental PD-L1 concentrations were then determined (h)

To start, each non-transformed cell model (Fig. 2c) was simulated until the system reached homeostatic steady state aligning it to a normal cell non-tumorigenic physiology. This established the control baseline for PD-L1 expression. Cell line-specific mutation profiles (Fig. 2a, b) were annotated into the cancer physiology network model (Fig. 2d), and it was simulated to induce the cell line-specific states (Fig. 2e) and to predict cell line-specific dysregulated pathways. The time required to achieve a network varied depending upon the complexity of the profile definition.

Simulation model predictions

Cell line-specific PD-L1 expression (Fig. 2f) was reported as a percent change with respect to non-tumorigenic baseline controls and calculated within each cell line separately. The percent change was calculated as ((D/C)-1)*100, where C is the absolute value of the non-tumorigenic baseline control (µM) and D is the absolute value of the biomarker obtained in the cell line-specific network (µM).

Cell culture

Predicted PD-L1 expression was verified against observed PD-L1 expression on the same cell lines grown in culture (Fig. 2g, h). All cell lines were grown and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37 °C in media containing 100 units/ml penicillin (Life Technologies, Madison, WI) and 100 units/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies). MM.1S and U266B1 were grown in high-glucose RPMI-1640 with l-glutamine, HEPES (ATCC, Manassas, VA), and 10 % (MM.1S) or 15 % (U266B1) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (ATCC).

SCC4 was grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium: F-12 (DMEM: F-12) containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 % nonessential amino acids (ATCC), 400 ng/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO), and 10 % FBS (ATCC). SCC15, SCC25, and UM-SCC84 were grown in Lymphocyte Growth Media-3 (LGM-3) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), and 10 % FBS (ATCC). UM-SCC19, UM-SCC92, and UM-SCC99 were grown in DMEM containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 % nonessential amino acids (ATCC), and 10 % FBS (ATCC).

PD-L1 reactivity has been observed by IHC on oral keratinocytes [33], and primary gingival epithelial (GE) keratinocyte cell lines GE365 and GE376 were used as PD-L1+ expression controls. GE keratinocytes, prepared in a previous study [34], were grown in keratinocyte-SFM with l-glutamine, human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF 1-53), bovine pituitary extract (BPE) (Gibco Life Sciences, Grand Island, NY), and 10 % FBS (ATCC).

PD-L1 ELISA

Whole cell PD-L1 concentrations were first determined. One milliliter of cultured cells (1.0 × 106 viable cells/ml) in high-glucose RPMI-1640 with l-glutamine, HEPES (ATCC), 100 units/ml penicillin (Life Technologies), and 100 units/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies) was added to wells of a 12-well culture plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Cell lines suspended in these minimal media have higher computational and experimental correlation rates. The effects of different cell culture media and additives on cell biomarker responses are dramatically reduced.

At 24 h, the 1.0 ml of RPMI-1640 was removed, the cells were lysed with 1.0 ml cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) containing 1.0 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Cell Signaling Technologies), and the lysate was stored at −80 °C. PD-L1 concentrations (3 replications) were then determined on MM, SCC, and GE keratinocyte lysates (ELISA, Cusabio Biotech Co., Ltd., Wilmington, DE) using the manufacturers protocol.

PD-L1 IHC

Cell surface PD-L1 expression was determined by IHC. One milliliter of cultured cells (1.0 × 106 viable cells/ml) in the minimal media described above was incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. At 24 h, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (400 RCF, Eppendorf 5810R, Brinkmann Instruments, Inc., Westbury, NY) at 4 °C for 5 min, fixed in 10.0 % neutral buffered formalin at room temperature, and suspended in 1.0 % Bacto Agar (Becton, Dickinson, and Co., Sparks, MD)−1.25 % gelatin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Bacto Agar–gelatin punches were made, and plugs containing cells were immobilized together in a 12-plug array using molten Bacto Agar–gelatin [34] and processed for microtomy as recently described [35].

IHC was performed by the University of Iowa Diagnostic Laboratories (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Cell antigens were unmasked in citrate buffer, pH 6.0 at 125 °C for 5 min (Decloaker, Biocare Medical, Concord, CA), and sections were treated in 3 % H2O2 for 8 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Primary PD-L1 antibody (17952-1-AP CD274, ProteinTech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL) diluted 1:250 in Dako diluent (Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA) was added, and sections were washed with Dako wash buffer (Dako North America, Inc.). Sections without primary PD-L1 antibody were included as negative section controls. After 60 min, PD-L1 reactivity on all sections was developed using Dako EnVision + System-HRP Labeled Polymer Anti-Rabbit (Dako North America, Inc.) and enhanced with Dako DAB enhancer (Dako North America, Inc.). Sections were counterstained with Leica hematoxylin. On negative antibody control slides, the same secondary antibody was used on the positive and negative control slides for 30 min at room temperature (Dako EnVision + System-HRP Labeled Polymer Anti-Rabbit, Dako North America, Inc.). The percent of PD-L1+ cells/total cells were counted on each section. Human pancreas and human tonsil tissues were used as IHC-positive and IHC-negative controls, respectively.

PD-L1 flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as recently described [35] to confirm cell surface expression of PD-L1. Briefly, 0.5 ml containing 0.5 × 105 viable cells in their respective media was incubated without and with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were stained with antihuman APC-CD274 (563741 PD-L1, BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA), stained with Live/Dead Fixable Green Dead Cell Stain (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and examined using an LSR II Violet Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Samples stained also with an isotype control (APC mouse IgG1 κ, BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA). Additional controls included unstained cells. Flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

Analogous two-way fixed effect ANOVA was fit to the PD-L1 concentrations determined by ELISA (JMP10, Version 10.0, SAS, Cary, NC). Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the T test. A 0.05 level was used to determine statistically significant differences.

Results

Predictive computational simulation models

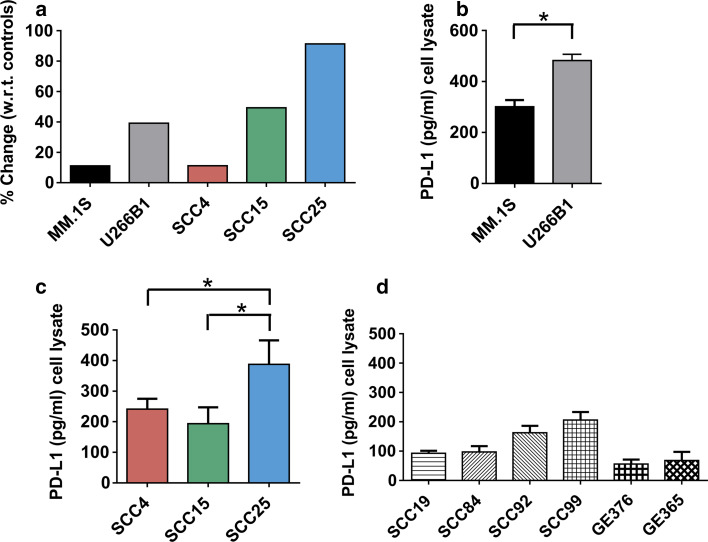

Simulation models were constructed to predict PD-L1 expression in MM and SCC cell lines. Cancer cell line mutations were first identified, assessed for mutational effects on gene function, converted into a computational format, and imported into the simulation workflow converting non-transformed cell models into dynamic cancer cell line-specific simulation models. Results were reported as percentage change with respect to the normal cell non-tumorigenic state and PD-L1 expression varied among MM and SCC cell line-specific simulation models. In MM cell lines, the percentage change of U266B1 (39.2 %) was greater than the percentage change of MM.1S (11.1 %) (Fig. 3a). In SCC cell lines, the percentage change of SCC25 (91.3 %) was greater than the percentage changes of SCC15 (49.3 %) and SCC4 (11.1 %) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Predicted PD-L1 percent expression with respect to (w.r.t.) controls (a) and the observed ELISA PD-L1 pg/ml concentration (b, c) in MM cell lines MM.1S and U266B1 and oral SCC cell lines SCC4, SCC15, and SCC25. *= p < 0.05. For comparison, the ELISA PD-L1 pg/ml concentrations are shown for other oral SCC cell lines SCC19, SCC84, SCC92, and SCC99 and GE keratinocytes GE376 and GE365 (d)

PD-L1 ELISA

Total whole cell PD-L1 concentrations were determined in MM (Fig. 3b), SCC (Fig. 3c, d), and GE keratinocyte (Fig. 3d) cell lysates using an ELISA. MM cell lysates ranged from 275.2 to 528.8 pg/ml PD-L1. U266B1 cell lysates contained more PD-L1 (482.4 ± 24.4 standard error pg/ml) than MM.1S (301.1 ± 25.9 standard error pg/ml) (Fig. 3b). SCC cell lysates ranged from 57.5 to 539.8 pg/ml PD-L1 (Fig. 3c). SCC25 cell lysates contained the most PD-L1 (387.6 ± 78.3 standard error pg/ml) and UM-SCC19 cell lysates contained the least (92.7 ± 8.7 standard error pg/ml). GE keratinocyte lysates ranged from 29.6 to 126.7 pg/ml PD-L1. GE365 cell lysates contained more PD-L1 (68.2 ± 29.3 standard error pg/ml) than GE376 (56.0 ± 15.2 standard error pg/ml) (Fig. 3d).

The concentrations of PD-L1 in MM and SCC cell lysates matched the percent of PD-L1 expression predicted to occur in these cells based on their mutational profile signatures (Table 1). The PD-L1 expression for U266B1 was greater than MM.1S, the PD-L1 expression for SCC25 was greater than SCC4, and the PD-L1 expression for SCC25 was greater than SCC15. However, the observed and predicted expression for SCC4 and SCC15 did not match. The mismatch was simply due to the lack of significant difference between the concentrations of PD-L1 in SCC4 and SCC15 cell lysates (p < 0.05), and a match could not be made.

Table 1.

Percentage changes of PD-L1 expression with respect to control baselines were determined and then verified against observed PD-L1 expression by ELISA, IHC, and flow cytometry on the same multiple myeloma (MM) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cell lines grown in culture

| Predicted PD-L1+ expression (%) | Observed PD-L1+ expression (ELISA) | Observed PD-L1+ expression (IHC) | Observed PD-L1+ expression (Flow cytometry) | Mismatch/match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U266B1 (39.2 %) > MM.1S (11.1 %) | U266B1 > MM.1S (p < 0.05) | U266B1 (9.0 %) > MM.1S (7.7 %) | U266B1 (0.2 %) > MM.1S (0.1 %) | Match |

| SCC15 (49.3 %) > SCC4 (11.1 %) | SCC4 > SCC15 (p > 0.05) ns | SCC15 (17.5 %) > SCC4 (4.0 %) | SCC15 (7.4 %) > SCC4 (1.8 %) | Mismatch/match |

| SCC25 (91.3 %) > SCC4 (11.1 %) | SCC25 > SCC4 (p < 0.05) | SCC25 (23.8 %) > SCC4 (4.0 %) | SCC25 (24.0 %) > SCC4 (1.8 %) | Match |

| SCC25 (91.3 %) > SCC15 (49.3 %) | SCC25 > SCC15 (p < 0.05) | SCC25 (23.8 %) > SCC15 (17.5 %) | SCC25 (24.0 %) > SCC15 (7.4 %) | Match |

PD-L1 IHC

PD-L1 reactivity was seen in the cytoplasm of some cells and on the surface of other cells (Fig. 4a–e). PD-L1 reactivity was specific. It was absent in the primary and secondary antibody negative controls. The percent of PD-L1+ MM and SCC cells matched the percent of PD-L1 expression predicted to occur in these cells based on their mutational profile signatures (Table 1). The numbers of PD-L1+ cells varied depending upon the cell line and ranged from 4.0 to 23.8 % (Fig. 4f). PD-L1 reactivity on U266B1 was greater than MM.1S, the reactivity of PD-L1 on SCC25 was greater than SCC4, the reactivity of PD-L1 on SCC25 was greater than SCC15, and the reactivity of PD-L1 on SCC15 was greater than SCC4 (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Detection of PD-L1 by IHC and flow cytometry on MM cell lines MM.1S (a) and U266B1 (b) and on oral SCC cell lines SCC4 (c), SCC15 (d), and SCC25 (e). The percentage of PD-L1+ cells in IHC (f) and flow cytometry (g) are compared

PD-L1 flow cytometry

Cell surface PD-L1 is the major factor in influencing anti-tumor immune responses. Here, flow cytometry was used to validate cell surface expression of PD-L1 in MM and SCC cell lines (Fig. 4a–e). PD-L1 reactivity was specific. The percent PD-L1+ cells increased in MM and SCC cell lines treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) as a positive control (data not shown) compared to MM and SCC cell lines not treated. The percent of PD-L1+ MM and SCC cells (Fig. 4g) matched the percent of PD-L1+ expression predicted to occur in these cells. PD-L1 reactivity a) on U266B1 was greater than MM.1S, b) on SCC25 was greater than SCC4, c) on SCC25 was greater than SCC15, and d) on SCC15 was greater than SCC4 (Table 1).

Discussion

Detecting PD-L1 on cancer cells is important in cancer diagnosis and as a clinical predictor of cancer immunotherapy treatment success for both anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies [36]. For better patient outcomes, there is a critical need to improve methods to accurately affirm PD-L1 expression. Determining PD-L1 reactivity in tumors using IHC can be variable. Determining sPD-L1 in serum or plasma can also be variable with differences associated with the collection methods, the samples (e.g., serum or plasma), and the assay methods [15]. Here, we created predictive computational simulation models containing cell line-specific genomic signatures to fill this gap and to predict PD-L1 expression with a validated, cancer network model. We found that computational models predicting PD-L1 expression correlated with observed PD-L1 expression by ELISA, IHC, and flow cytometry on the same cells grown in culture.

These simulation models have a variety of applications. They could be used a) after cancer diagnosis to aid in selecting patients for PD-L1 immunotherapy, b) to predict clinical immunotherapy treatment success, c) to predict the influence of various factors on the production and regulation of PD-L1, d) to differentiate PD-L1 drug responders from PD-L1 drug non-responders, and e) to show the intermediate steps in cell signaling pathways where genomic signatures influence the downstream effects on PD-L1 expression (Fig. 5). As per the network representation, PD-L1 expression is regulated by the different transcription factors that are modulated by the upstream signals and the translated PD-L1 is then present as a membrane bound fraction.

Fig. 5.

Computational simulation models of MM and oral SCC cell lines clearly demonstrate that cell line-specific genomics influence cell signaling and downstream effects on PD-L1 expression. In these models, production of PD-L1 is influenced via a number of intermediate proteins in the signaling pathways

MM is a hematologic disease characterized by the infiltration, expansion, and survival of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow [37]. There are 30,330 estimated new cases of MM in the USA in 2016 (1.8 % of all new cancer cases) and 12,650 estimated deaths (2.1 % of all cancer deaths) [38]. The 5-year survival rate is 48.5 % [38]. Clinical trials suggest that MM responds to programmed death immunotherapy. Current anti-PD-1 trials for MM include pembrolizumab (NCT01953692), nivolumab (NCT01592370), and pidilizumab (NCT02077959), and current anti-PD-L1 trials for MM include BMS-936559 (NCT01452334, withdrawn), atezolizumab (NCT02431208), and MEDI4736 (NCT01693562).

SCCs are common neoplasms of oral tissues causally associated with genetic factors, human papillomavirus infections, and behavioral exposures to environmental carcinogens, such as alcohol and tobacco consumption [39–41]. There are 48,330 estimated new cases of oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the USA in 2016 (2.9 % of all new cancer cases) and 9570 estimated deaths in 2016 (1.6 % of all cancer deaths) [42]. The 5-year survival rate, regardless of tumor stage/grade of tumor differentiation, is 64.0 % [42]. Clinical trials suggest that SCC responds to programmed death immunotherapy. Current anti-PD-1 trials for SCC include pembrolizumab (NCT01848834) and nivolumab (NCT02105636), and current anti-PD-L1 trials for SCC include atezolizumab (NCT01375842), avelumab (NCT01772004), and MEDI4736 (NCT01693562, NCT02207530).

Computational models to predict PD-L1 expression could enhance the clinical outcomes of these trials and improve treatment success rates. Recent studies have confirmed that tumor cell PD-L1 expression is highly correlated with objective responses [43]. In a phase I trial with nivolumab, patients with ≥5 % IHC PD-L1+ tumor cells had an objective response rate of 36 % whereas patients with IHC PD-L1− tumor cells did not have any objective response rate [44]. In another phase I trial with nivolumab, patients with IHC PD-L1+ tumor cells had an objective response rate of 44 % whereas patients with IHC PD-L1− tumor cells had an objective response rate of 17 % [45]. In another trial with MPDL3280A, patients with >5 % IHC PD-L1+ bladder cancer cells had an objective response rate of 43.3 % whereas patients with IHC PD-L1− tumor cells had an objective response rate of 11.4 % [46]. Finally, utilizing MPDL3280A with advanced or metastatic solid tumors, patients with >5 % IHC PD-L1+ tumor cells had an objective response rate of 39 % whereas patients with IHC PD-L1− tumor cells had an objective response rate of 13.0 % [47].

SCC cell lines do not uniformly express PD-L1 [4, 48, 49]. PD-L1 has a focal or diffuse distribution on the cell membrane and/or in the cell cytoplasm, which may be influenced by environmental stimuli [16]. We observed similar trends, and PD-L1 reactivity was focal or diffuse on the cell membrane and in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 4a–e). PD-L1 has also been detected at different concentrations with flow cytometry in unstimulated and stimulated SCC cell lines [48, 49]. Here, we detected differences in PD-L1 concentrations with ELISA, IHC, and flow cytometry in unstimulated MM and SCC cell lines (Fig. 3b, c). Observed PD-L1 expression matched the predicted PD-L1 expression (Table 1). The one mismatch seen between the predicted and the observed expression was due to the lack of significant difference between the observed concentrations of PD-L1 in SCC4 and SCC15 cell lysates.

In our models, intrinsic cellular control of PD-L1 expression was influenced via a number of different signaling pathways (Fig. 5). This is supported by other findings in the literature and the signaling pathways modeled for PD-L1 expression for MM and SCC by our simulated models, which are similar to that proposed by Ritprajak and Azuma for both extrinsic and intrinsic control of PD-L1 in a variety of cell types [16]. PD-L1 expression is induced in SCC cell lines and GE keratinocytes by IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β [48–50]. These and other induction stimuli likely act via toll-like receptors (TLRs) or interferon (IFN) receptors to modulate the expression and activation of PD-L1 expression through various downstream signaling molecules, such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) that affect cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, and activation or regulation of transcription factors [51–53]. These further regulate the nuclear translocation of transcription factors to the PD-L1 promoter [16].

Induction stimuli are processed through extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathways via epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), B-raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF-V600E), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2) (e.g., mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAP2K1) and MAP2K2), ERK1/2 (e.g., MAPK3 and MAPK1), and Jun proto-oncogene (c-Jun). High levels of PD-L1 expression are processed through signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 and ERK signaling pathways [54, 55]. Induction stimuli are also processed through the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (Erb) signaling pathway via neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT), mTOR, and STAT3 as well as the IFN-γ pathway via IFNG, interferon gamma receptor 1 (IFNGR1), STAT1, and interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1). Pathway signals converge to activation factors activator protein-1 (AP-1), STAT1, STAT3, and IRF1 leading to transcription of PD-L1 genes. Tumors are driven by multiple aberrations in many of these genes that can in turn influence the expression levels of PD-L1 on the tumor cell and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

In conclusion, we created computational simulation models containing cell line-specific genomic signature profiles to accurately predict PD-L1 expression on MM and SCC cell lines. Results from these models show that cell genomics play an integral role by influencing cell signaling and downstream effects on PD-L1 expression. Computation-based prediction of PD-L1 expression could add value to analysis of PD-L1 expression in human cancer tissues. However, analysis of tumor cell lines could be misleading in predicting PD-L1 expression in tumor tissues where multiple inflammatory factors are involved in regulation of PD-L1. Given that PD-L1 expression by tumor cells has been considered a hallmark of adaptive resistance of cancers, conclusion based on tumor cells alone might be less significant and future prediction models should be addressed in context with immune cells. This includes the cell-to-cell contact that occurs among cancer cells, T cells, and dendritic cells in the tumor microenvironment. In the future, we anticipate that these models will also include the roles of other immunosuppressive chemokines and cytokines and the roles of immune cells. Together these models will be able to accurately predict PD-L1 expression of cancer cells, improve the potential of PD-L1 as a biomarker, and retain PD-L1 as an important clinical predictor of treatment success.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (R01 DE014390) and a training grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (T90 DE023520). The data presented herein were obtained at the Flow Cytometry Facility, which is a Carver College of Medicine/Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center core research facility at the University of Iowa. The facility is funded through user fees and the generous financial support of the Carver College of Medicine, Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Iowa City Veteran’s Administration Medical Center. The authors would like to thank Patricia Conrad for preparation of the figures.

Abbreviations

- AKT

V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog

- AP-1

Activator protein-1

- BRAF-V600E

B-raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase

- c-Jun

Jun proto-oncogene

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GE

Gingival epithelial

- IFNG

Interferon gamma

- IFNGR1

Interferon gamma receptor 1

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IRF1

Interferon regulatory factor 1

- JAK/STAT

Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT)

- MAP2K1

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- mTOR

Mechanistic target of rapamycin

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- NRAS

Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- PIK3CA

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- sPD-L1

Soluble PD-L1

- STAT1

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Kim A. Brogden has had a cooperative research and development agreement with Cellworks Group Inc., San Jose, CA. Emily A. Lanzel, M. Paula Gomez Hernandez, Amber M. Bates, Christopher N. Treinen, Emily E. Starman, Carol L. Fischer, Janet M. Guthmiller, Georgia K. Johnson, and Kim A. Brogden declare no competing financial interests in the findings of this study or with Cellworks Group Inc., San Jose, CA, USA, or Cellworks Research India Ltd, Whitefield, Bangalore, India. Taher Abbasi and Shireen Vali are employed by Cellworks Group Inc., San Jose, CA, USA, and Deepak Parashar is employed by Cellworks Research India Ltd, Whitefield, Bangalore, India.

References

- 1.Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:219–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedoeem A, Azoulay-Alfaguter I, Strazza M, Silverman GJ, Mor A. Programmed death-1 pathway in cancer and autoimmunity. Clin Immunol. 2014;153:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, Lennon VA, Celis E, Chen L. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm0902-1039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong H, Chen L. B7-H1 pathway and its role in the evasion of tumor immunity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2003;81:281–287. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swaika A, Hammond WA, Joseph RW. Current state of anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 agents in cancer therapy. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng SY, Otsuji M, Gorski K, Huang X, Slansky JE, Pai SI, Shalabi A, Shin T, Pardoll DM, Tsuchiya H. B7-DC, a new dendritic cell molecule with potent costimulatory properties for T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:839–846. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhaijee F, Anders RA. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker: is Absence of Proof the Same as Proof of Absence? JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:54–55. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLaughlin J, Han G, Schalper KA, Carvajal-Hausdorf D, Pelekanou V, Rehman J, Velcheti V, Herbst R, LoRusso P, Rimm DL. Quantitative Assessment of the Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:46–54. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunshine J, Taube JM. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;23:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frigola X, Inman BA, Lohse CM, Krco CJ, Cheville JC, Thompson RH, Leibovich B, Blute ML, Dong H, Kwon ED. Identification of a soluble form of B7-H1 that retains immunosuppressive activity and is associated with aggressive renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1915–1923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Wang Q, Shi B, Xu P, Hu Z, Bai L, Zhang X. Development of a sandwich ELISA for evaluating soluble PD-L1 (CD274) in human sera of different ages as well as supernatants of PD-L1 + cell lines. Cytokine. 2011;56:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng Z, Shi F, Zhou L, Zhang MN, Chen Y, Chang XJ, Lu YY, Bai WL, Qu JH, Wang CP, Wang H, Lou M, Wang FS, Lv JY, Yang YP. Upregulation of circulating PD-L1/PD-1 is associated with poor post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Z, Bu Z, Liu X, Zhang L, Li Z, Wu A, Wu X, Cheng X, Xing X, Du H, Wang X, Hu Y, Ji J. Level of circulating PD-L1 expression in patients with advanced gastric cancer and its clinical implications. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:104–111. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2014.02.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossille D, Gressier M, Damotte D, Maucort-Boulch D, Pangault C, Semana G, Le Gouill S, Haioun C, Tarte K, Lamy T, Milpied N, Fest T, Groupe Ouest-Est des Leucemies et Autres Maladies du S, Groupe Ouest-Est des Leucemies et Autres Maladies du S High level of soluble programmed cell death ligand 1 in blood impacts overall survival in aggressive diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma: results from a French multicenter clinical trial. Leukemia. 2014;28:2367–2375. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritprajak P, Azuma M. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of expression of the immunoregulatory molecule PD-L1 in epithelial cells and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Jiang CC, Jin L, Zhang XD. Regulation of PD-L1: a novel role of pro-survival signalling in cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:409–416. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman-Leikin RE, Salwen HR, Herst CV, Variakojis D, Bian ML, Le Beau MM, Selvanayagan P, Marder R, Anderson R, Weitzman S, et al. Characterization of a novel myeloma cell line, MM.1. J Lab Clin Med. 1989;113:335–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenstein S, Krett NL, Kurosawa Y, Ma C, Chauhan D, Hideshima T, Anderson KC, Rosen ST. Characterization of the MM.1 human multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines: a model system to elucidate the characteristics, behavior, and signaling of steroid-sensitive and -resistant MM cells. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:271–282. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(03)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson K, Bennich H, Johansson SG, Ponten J. Established immunoglobulin producing myeloma (IgE) and lymphoblastoid (IgG) cell lines from an IgE myeloma patient. Clin Exp Immunol. 1970;7:477–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchhagen DL, Worsham MJ, Dyke DL, Carey TE. Two regions of homozygosity on chromosome 3p in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: comparison with cytogenetic analysis. Head Neck. 1996;18:529–537. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199611/12)18:6<529::AID-HED7>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CL, Grandis JR, Carey TE, Gollin SM, Whiteside TL, Koch WM, Ferris TL, Lai SY. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines: established models and rationale for selection. Head Neck. 2007;29:163–188. doi: 10.1002/hed.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner JC, Graham MP, Kumar B, Saunders LM, Kupfer R, Lyons RH, Bradford CR, Carey TE. Genotyping of 73 UM-SCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Head Neck. 2010;32:417–426. doi: 10.1002/hed.21198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joly S, Compton LM, Pujol C, Kurago ZB, Guthmiller JM. Loss of human beta-defensin 1, 2, and 3 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24:353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martelotto LG, Ng CK, De Filippo MR, Zhang Y, Piscuoglio S, Lim RS, Shen R, Norton L, Reis-Filho JS, Weigelt B. Benchmarking mutation effect prediction algorithms using functionally validated cancer-related missense mutations. Genome Biol. 2014;15:484. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0484-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sim NL, Kumar P, Hu J, Henikoff S, Schneider G, Ng PC (2012) SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 40(Web Server issue):W452-457. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doudican NA, Kumar A, Singh N, Nair PR, Lala DA, Basu K, Talawdekar AA, Sultana Z, Tiwari K, Tyagi A, Abbasi T, Vali S, Vij R, Fiala M, King J, Perle M, Mazumder A. Personalization of cancer treatment using predictive simulation. J Transl Med. 2015;13:43. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0399-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doudican NA, Mazumder A, Kapoor S, Sultana Z, Kumar A, Talawdekar A, Basu K, Agrawal A, Aggarwal A, Shetty K, Singh NK, Kumar C, Tyagi A, Singh NK, Darlybai JC, Abbasi T, Vali S. Predictive simulation approach for designing cancer therapeutic regimens with novel biological mechanisms. J Cancer. 2014;5:406–416. doi: 10.7150/jca.7680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones MV, Calabresi PA. Agar-gelatin for embedding tissues prior to paraffin processing. Biotechniques. 2007;42:569–570. doi: 10.2144/000112456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poulsen C, Mehalick LA, Fischer CL, Lanzel EA, Bates AM, Walters KS, Cavanaugh JE, Guthmiller JM, Johnson GK, Wertz PW, Brogden KA. Differential cytotoxicity of long-chain bases for human oral gingival epithelial keratinocytes, oral fibroblasts, and dendritic cells. Toxicol Lett. 2015;237:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carbognin L, Pilotto S, Milella M, Vaccaro V, Brunelli M, Calio A, Cuppone F, Sperduti I, Giannarelli D, Chilosi M, Bronte V, Scarpa A, Bria E, Tortora G. Differential activity of Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab and MPDL3280A according to the tumor expression of programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1): sensitivity analysis of trials in melanoma, lung and genitourinary cancers. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0130142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landgren O, Morgan GJ. Biologic frontiers in multiple myeloma: from biomarker identification to clinical practice. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:804–813. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (2015) SEER STAT fact sheets: myeloma. In: SEER cancer statistics review, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed 15 Sept 2016

- 39.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su S, Chien M, Lin C, Chen M, Yang S. RAGE gene polymorphism and environmental factor in the risk of oral cancer. J Dent Res. 2015;94:403–411. doi: 10.1177/0022034514566215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–582. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (2015) SEER STAT fact sheets: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. In: SEER cancer statistics review, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html. Accessed 15 Sept 2016

- 43.Taube JM, Klein A, Brahmer JR, Xu H, Pan X, Kim JH, Chen L, Pardoll DM, Topalian SL, Anders RA. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5064–5074. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, Leming PD, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Drake CG, Pardoll DM, Chen L, Sharfman WH, Anders RA, Taube JM, McMiller TL, Xu H, Korman AJ, Jure-Kunkel M, Agrawal S, McDonald D, Kollia GD, Gupta A, Wigginton JM, Sznol M. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grosso J, Horak CE, Inzunza D, Cardona DM, Simon JS, Gupta AK, Sankar V, Park J, Kollia G, Taube JM, Anders R, Jure-Kunkel M, Novotny JJ, Taylor CR, Zhang X, Phillips T, Simmons P, Cogswell J (2013) Association of tumor PD-L1 expression and immune biomarkers with clinical activity in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors treated with nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538). J Clin Oncol 31: (suppl; abstr 3016)

- 46.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, Braiteh FS, Loriot Y, Cruz C, Bellmunt J, Burris HA, Petrylak DP, Teng SL, Shen X, Boyd Z, Hegde PS, Chen DS, Vogelzang NJ. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature. 2014;515:558–562. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbst RS, Gordon MS, Fine GD, Sosman JA, Soria J-C, Hamid O, Powderly JD, Burris HA, Mokatrin A, Kowanetz M, Leabman M, Anderson M, Chen DS, Hodi FS (2013) A study of MPDL3280A, an engineered PD-L1 antibody in patients with locally advanced or metastatic tumors. J Clin Oncol 31 (suppl; abstr 3000)

- 48.Strome SE, Dong H, Tamura H, Voss SG, Flies DB, Tamada K, Salomao D, Cheville J, Hirano F, Lin W, Kasperbauer JL, Ballman KV, Chen L. B7-H1 blockade augments adoptive T-cell immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6501–6505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsushima F, Tanaka K, Otsuki N, Youngnak P, Iwai H, Omura K, Azuma M. Predominant expression of B7-H1 and its immunoregulatory roles in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youngnak-Piboonratanakit P, Tsushima F, Otsuki N, Igarashi H, Machida U, Iwai H, Takahashi Y, Omura K, Yokozeki H, Azuma M. The expression of B7-H1 on keratinocytes in chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease and its regulatory role. Immunol Lett. 2004;94:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loke P, Allison JP. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are differentially regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5336–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931259100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu J, Hamrouni A, Wolowiec D, Coiteux V, Kuliczkowski K, Hetuin D, Saudemont A, Quesnel B. Plasma cells from multiple myeloma patients express B7-H1 (PD-L1) and increase expression after stimulation with IFN-{gamma} and TLR ligands via a MyD88-, TRAF6-, and MEK-dependent pathway. Blood. 2007;110:296–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qian Y, Deng J, Geng L, Xie H, Jiang G, Zhou L, Wang Y, Yin S, Feng X, Liu J, Ye Z, Zheng S. TLR4 signaling induces B7-H1 expression through MAPK pathways in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:816–821. doi: 10.1080/07357900801941852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marzec M, Zhang Q, Goradia A, Raghunath PN, Liu X, Paessler M, Wang HY, Wysocka M, Cheng M, Ruggeri BA, Wasik MA. Oncogenic kinase NPM/ALK induces through STAT3 expression of immunosuppressive protein CD274 (PD-L1, B7-H1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20852–20857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810958105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto R, Nishikori M, Tashima M, Sakai T, Ichinohe T, Takaori-Kondo A, Ohmori K, Uchiyama T. B7-H1 expression is regulated by MEK/ERK signaling pathway in anaplastic large cell lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2093–2100. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]