Abstract

Management, coordination and logistics were critical for responding effectively to the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, and the duration of the epidemic provided a rare opportunity to study the management of an outbreak that endured long enough for the response to mature. This qualitative study examines the structures and systems used to manage the response, and how and why they changed and evolved. It also discusses the quality of relationships between key responders and their impact. Early coordination mechanisms failed and the President took operational control away from the Ministry of Health and Sanitation and established a National Ebola Response Centre, headed by the Minister of Defence, and District Ebola Response Centres. British civilian and military personnel were deeply embedded in this command and control architecture and, together with the United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response lead, were the dominant coordination partners at the national level. Coordination, politics and tensions in relationships hampered the response, but as the response mechanisms matured, coordination improved and rifts healed. Simultaneously setting up new organizations, processes and plans as well as attempting to reconcile different cultures, working practices and personalities in such an emergency was bound to be challenging.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘The 2013–2016 West African Ebola epidemic: data, decision-making and disease control’.

Keywords: Ebola, command and control, management, outbreak, military, Sierra Leone

1. Introduction

Perhaps more than for any other outbreak in recent times, sound management, coordination and logistics were critical for responding effectively to the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone (table 1).

Table 1.

Glossary

| key body/actor | role |

|---|---|

| national | |

| Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS) | Led the response from March to October 2014, then participated at various levels, from chairing the ‘pillars’ to providing the bulk of the frontline workforce. |

| Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces (RSLAF) | Played a key role in several aspects, from staffing the NERC and building and running Ebola treatment units, to managing dead body collection and burials. |

| National Ebola Response Centre (NERC) | Body responsible for the national operational aspect of the response, setting strategy, designing policy and directing major operations, as well as collating and interpreting data from across the country to inform the response. |

| District Ebola Response Centre (DERC) | Command and control centre established in all districts to execute response interventions through the ‘pillars,’ such as delivering patients to beds, burying bodies, managing quarantines, contact tracing. |

| international | |

| Combined joint interagency task force (CJIATF) | The British civilian–military team that delivered the UK government's response, a £427 million wide-ranging package. |

| UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER) | Coordinated the relevant UN agencies, and to some extent donors and NGOs, and provided logistics, training, financial support and aircraft service. |

| World Health Organization (WHO) | Advisory role in the NERC, co-led the case management and surveillance pillars at both the national and district levels and, after January 2015, along with the CDC, provided most of the epidemiologists for the response. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | A leading partner in the technical response, advising the NERC, conducting surveillance work, outbreak investigation, diagnostic testing, vaccine research, training and a host of other activities. |

| Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) | Key implementers of the response on the ground, involved in a wide variety of activities ranging from the manning of treatment and isolation facilities and provision of quarantine supplies to the management of burials and social mobilization activities. |

| glossary of terms | |

| logistics | Functions that support emergency operations, including estimating equipment needs, procurement and distribution of supplies, transport of patients and samples and other response implementation support. |

| Operation Northern Push | A June 2015 NERC initiative to surge contact tracers and social mobilization into two problematic districts in the North of the country. |

| situation room | The hub of the NERC that gathered real-time information from the field through the DERCs and interpreted it in order to inform decision-making in the response. |

| social mobilization | Activities to raise public awareness through the delivery of public health messages and to engage communities in the effort to stop the spread of Ebola. |

| technical pillars | Structure around which the technical aspects, or interventions on the ground were organized and run. Responsible for providing technical guidance for the response. |

| UN cluster system | Coordination mechanism for UN humanitarian operations whereby response groups working on the same aspect are clustered together in sectors, such as shelter or health. |

| Western Area | A densely populated area of Sierra Leone that encompasses the capital, Freetown and its outskirts. It was an outbreak hotspot. |

The early part of the outbreak response in Sierra Leone was characterized by confusion, chaos and denial. The government was unable to mount a robust response, the World Health Organization (WHO) did not mobilize the level of assistance and expertise expected—a failure that has been widely criticized [2,3]—and the rest of the international community was slow to react to the alert sounded by Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF), who recognized the severity of the threat early on [4].

The architecture that was put in place in October 2014—five months into the outbreak—to manage what at the time was a rapidly expanding humanitarian crisis was a cornerstone of the country's response strategy.

2. Scope and methodology

This study seeks to understand how the response to the 2013–2016 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone was organized and run. It examines the structures and systems put in place to manage the response and how and why those evolved as the response matured, with particular emphasis on the third generation of response architecture. It also seeks insight into the quality of the relationships between key responders and their impact, and explores some of the challenges responders experienced around the command and control of the response. This paper is an abridged version of a longer paper published by Chatham House in March 2017.

Qualitative research methods were used. The experience and perspectives of more than 70 key responders were ascertained through semi-structured and unstructured telephone and/or face-to-face interviews between July 2015 and August 2016. Field research was conducted over one week in September 2015. Interviewees included a broad range of actors involved in the management of the response at both the national and district levels, including those working for non-governmental organizations (NGOs), United Nations (UN) agencies and donor agencies; Sierra Leonean government officials, military, ministers and staff; British civil and military sources; diplomats, advisors, independent contractors, doctors, nurses, epidemiologists and others embedded in the response structures.

To encourage the disclosure of sensitive information and candid views, all interviewees were given anonymity and all quotations are anonymous. Interviews were supplemented with a review of relevant published and unpublished reports and papers, official statements, news reports, meeting minutes, recordings of testimony and other documents obtained by Chatham House.

In §3, this paper starts by briefly describing the early response mechanisms and their functioning and demise. Section 4 discusses the early engagement of the British, Sierra Leone's most significant donor, and how their assessment of response capacities and mechanisms contributed to the establishment of the National Ebola Response Centre (NERC). The paper then outlines in §5 the structure and systems of the NERC, its functional challenges, the quality of the relationships between key responders, and their impact and evolution. It then describes the origin, structure and functioning of the District Ebola Response Centres (DERCs), their challenges and evolution in §6. Political challenges are described in §7, and the phasing out of the NERC and DERC structure is discussed in §8. Finally, in §9, the paper draws some conclusions about the roles played by the various key responders and the factors influencing the establishment and outcome of the mechanisms used to respond to the outbreak.

3. Early response mechanisms: March–October 2014

(a). The National Ebola task force: March–July 2014

The earliest response coordination mechanism was the National Ebola task force, which was established in March 2014 [5], when the disease emerged in Guinea but before the first case was detected in Sierra Leone. The strategy included the Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS) starting awareness raising activities and surveillance in the border areas, and other preparations such as the training of laboratory technicians, healthcare workers and community surveillance teams. However, interviewees said these efforts were haphazard and ineffective.

Once Ebola was confirmed in the country on 25 May 2014 [6], the MOHS used the task force to organize the response on the ground around four technical ‘pillars’ that covered classic outbreak response activities, such as surveillance, case management, social mobilization and logistics [7].

Chaired by the Minister of Health and Sanitation, the task force convened daily and the early meetings attracted about 80 people, including the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) and other senior MOHS staff, representatives from other government departments, four UN agencies (WHO, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the World Food Programme (WFP)); donors and NGOs. However, interviewees reported that the mechanism was not effective. An interviewee who participated in the meetings said:

‘The National Ebola task force meetings were long and ineffective. The early coordination lacked leadership, focus and there was a lot of flailing around. There was a real issue around gripping the size of the problem.’

(b). The Ebola Operations Centre: July–October 2014

By the middle of July 2014, it was clear the task force mechanism was not working and the MOHS established an Ebola Operations Centre (EOC) on 11 July 2014 to serve as the response command and control centre (donor's unpublished slide presentation). Although the task force continued to meet and was considered the decision-making body, the daily meetings shifted to the EOC.

The EOC was co-chaired by the MOHS and WHO and housed in a small annex at the WHO offices in Freetown. Its core comprised MOHS and other government officials, representatives of UN agencies, MSF, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the International Rescue Committee. The United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) later joined, and others joined sporadically.

The technical pillars were led by a MOHS director and co-chaired by either a UN agency or the IFRC, with specific responsibilities divided among the partners: for example WHO co-chaired case management and surveillance, while UNICEF was on social mobilization, UNFPA on contact tracing and WFP on logistics. The IFRC co-chaired the burials pillar, which was added when coordination moved to the EOC. International NGOs gave important support to operations on the ground.

The EOC was judged to be highly dysfunctional, with lack of strategic planning, serious in-fighting within the MOHS, and arguments over money between the ministers of the various departments involved all hampering the response.

Several interviewees said the EOC was little more than a talking shop, while some said it served mainly as a technical review board for standard operating procedures for the technical pillars.

On the sidelines of the EOC, discussions between the MOHS and donors were reportedly frustrating in the absence of strategic and operational planning. While donors sought to determine what specifically needed to be paid for and how resourcing would be managed, officials would reportedly just keep quoting an amount and give vague categories. Donors said they turned to the WHO for a more specific needs analysis, to no avail.

The first case in Freetown was reported on 11 July 2014 and as the outbreak became more visible there that month, some international organizations started to get a sense that the real story was not being discussed in official circles.

Data sharing was a significant problem, and figures quoted by the MOHS did not match the WHO's, nor were they in alignment with what responders were reporting from the field. Several interviewees said that the WHO was not playing an independent role and that nobody in authority wanted to admit to the President how bad the situation was. Sources said there was no doubt the minister was playing down the severity of the outbreak and the MOHS's ability to cope with it. One UN agency responder who participated in the EOC at the time admitted that international responders who were there were ‘not strong enough’ to tell the minister it was not working. British participants in the response said they decided at that point that information coming out of the MOHS had to be ignored.

Several donors said they were telling the President everything was not fine, despite what the minister was reporting. It was argued that the 29 July 2014 death of the leading Sierra Leonean doctor on the frontline of the response was a wake-up call for the President [8].

On 30 July 2014, the President declared a state of emergency and the establishment of the Presidential task force on Ebola [9]. This task force, which was set up to supplement the EOC and facilitate the President's oversight of the response, included the various Ministries and was the body to which the EOC reported. Within two weeks, it was expanded to include development partners, political parties, legislators and civil societies and other Ebola responders and it convened once a week in day-long meetings presided over by the President. This mechanism was also widely judged have been ineffective and was later superseded.

The President visited the EOC on the 31 July 2014 and then on 9 August [10].

The first time he came, he only found two people there—the secretary and the cleaner. He was very upset. The second time he came, there were 10 people. It was a bit embarrassing for the WHO and the Ministry.

The President then put a staff member in the EOC. He later met with the CDC director in Freetown on 29 August 2014 and stated during the meeting that after consulting with the representatives of the UN, the WHO, the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and other donors he had decided to review the structure of the EOC [11]. He appealed to the international community to step up its support. Later that day he announced that the Minister of Health and Sanitation was to be replaced and the EOC reconstituted [12]. However, the new minister was not put in charge of the EOC, which was now to be led jointly by the CMO and the WHO, with a new operations coordinator to implement the response.

To fill the coordinator post, the President brought over from the United States a former Sierra Leone Minister of Social Welfare. Interviewees said the reform of the EOC brought more honesty to the system regarding the scale of the problem. Meanwhile, on the UN front, the WHO country representative had also been replaced. Interviewees said he was considered more credible than his predecessor and was prepared to challenge the MOHS, but that this did not translate into decisions at the EOC. A source from the donor community said coordination was poor and frustration with the inadequacy of the national response continued.

We were sitting in hours of meetings, where people suggested actions, but nobody took note or followed up and no one took any fundamental decisions. Very little had changed. We gave it about six weeks.

Before long, it became clear that despite the reform, the EOC was still not working. Sources said one of the problems was that its coordinator was not empowered with a mandate to hold the various ministries to account. It became clear that there needed to be a change in structure in order to have someone with such executive authority, sources said.

By September 2014 planeloads of healthcare workers and supplies were arriving in the country and some international responders were looking to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) to coordinate. Sources said resources were available, but they were not being spent because it was unclear what they should be spent on.

There was a huge vacuum. There was no operational plan, but a growing understanding of the need for one and it was obvious that a major international intervention was going to be necessary.

Within this context, senior officials from the WHO and the British government—the most significant donor to Sierra Leone—met in early September to work out what would be needed in order to install crisis management capabilities and operational capacity, and it was determined that the entity most likely to be able to bring that in was the British military [13].

Shortly after this meeting, on 19 September 2014, one day after a UN Security Council emergency session on the crisis declared the outbreak a threat to peace and security, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon established the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER), the first ever UN health emergency mission. It aimed to unify the UN approach to the crisis, with five objectives—stopping the outbreak, treating the infected, ensuring essential services, preserving stability and preventing further outbreaks [14].

4. Transition to a new response management system

The UK pushed for a leadership role, given its strong historical and bilateral relationship with Sierra Leone. The official call from the WHO and the Sierra Leonean government for the British to step up assistance and led the international effort came in early September 2014 [15].

Interviewees said that when the need for a major international response became obvious, one question put to President Koroma was whether he wanted a Level-3 UN humanitarian crisis designation, which would have entailed the government handing over control of the response to the UN and the mobilization of the OCHA-led cluster system to structure and coordinate response activities. Koroma reportedly said he did not want that mechanism triggered in Sierra Leone, which had recently emerged from under a UN Security Council mandate. Sources said that while the President did not want a Level-3 response in name, he was amenable for it be executed in practice, but that it had to be a Sierra Leone-led response.

The British knew they would have to come in at a scale that made a difference and began their main deployment on 21 September 2014 (unpublished UK military report). But they already had a sense that further engagement would probably be needed. Upon arrival, they set up a Combined Joint Interagency task force (CJIATF) comprising the various UK government agencies involved in the response. The team was led by a senior DFID director, with a Brigadier running CJIATF operations and the High Commissioner taking charge of the political relationships. Its headquarters in Freetown was set up to include a wide range of responders, including NGOs, UN agencies, the government, international epidemiologists and diplomats, and military responders from other countries. In the first 48 h, the CJIATF drew up an assessment of the level of the government's capacity, what systems were in place and how they were functioning. Leading elements of the UN and its agencies were consulted during this process, and as UNMEER gained the capacity to move beyond its own establishment, the UK revised its plans to become more coherent with UNMEER's. British sources said the intention was to be able hand over a stable and manageable situation.

The incapacity of the MOHS to manage the response was already clear, but there was another national structure that some argued should have been able to kick into gear when Ebola became a crisis. Sierra Leone's Office of National Security (ONS), which DFID had helped to set up years before, had a department responsible for disaster risk management, with a decentralized structure involving district disaster management committees and pre-existing links with the traditional chief governance structure. The British assessed the capacity of this institution and determined it would not be a viable candidate to build upon for managing the crisis, given the urgency. Other interviewees expressed a similar view of the unsuitability of the ONS to run the response.

The prospect of UNMEER taking the command and control role was also considered. Interviewees said the first UNMEER representative arrived in Sierra Leone in late September 2014 and that shortly thereafter there was a quick succession of visits from senior UN personnel, who laid out the vision of how the new body would work. Interviewees said this included deployment of resources to the districts, establishment of a district-level operational platform through which foreign medical teams would work and a structure through which other responders would work. A British responder said of UNMEER:

‘It sounded exactly right, but they couldn't lay out a view on how quickly they would be able to resource that and it became increasingly clear over time that they would struggle to resource it. All along our preference was that the UN would step in to that space, but when it was clear they didn't have capacity early on to do that, it was our view to work with them and as soon as they did have capacity we would have been delighted to have stepped out of that space. But the reality was that never happened through the life of the response.’

(a). Transfer of control from the MOHS to the NERC

The national response coordination mechanism that eventually became the cornerstone of Sierra Leone's operational strategy was, to a large degree, born out of the British assessment, which found a clear need for a government-led bespoke command and control hub through which to run the response. Other donors said they had simultaneously been advising the President of such a need. An interviewee from the CJIATF said:

‘We knew we needed to step into this space. So we went to State House and explained that the EOC wasn't working and offered to present the President with options. Within 24 h he called and asked to hear the options.’

One option presented was the concept of what was later dubbed the NERC, a completely new architecture that the British expressed a preference for. The President gave the green light in early October 2014. When he announced on 18 October 2014 that he was reconfiguring the response to establish the NERC, and placing at its helm the Minister of Defence as its Chief Executive Officer (CEO), with immediate effect, coordination of the response was taken out of the hands of the MOHS [16]. Some interviewees contended the Minister of Defence was chosen to be the NERC CEO not only because he had the political clout to hold other ministers to account, but also because it was considered he could work well with the British.

A vast majority of interviewees—both Sierra Leonean and international—strongly defended that move. They said that it was the right thing to do given the scale of the outbreak, the fact that it had escalated beyond a health issue to a humanitarian emergency, and the MOHS's inability to demonstrate that it could adequately manage the response, even though it had knock-on effects that undermined certain aspects of the response.

The MOHS was nevertheless integrated into the response, with a seat at the decision-making table in the NERC, but most notably it retained leadership of the pillars of the technical aspect of the response. Also, MOHS workers accounted for a significant portion of the frontline workforce.

5. The NERC: October 2014–December 2015

Spanning the responsibilities of both the MOHS and the ONS, the NERC was the third and final generation of the national response mechanism and was designed to provide national operational coherence, resourcing and direction. Compared with the previous coordination structures, the NERC established more of a separation between the technical and operational aspects of the response [17]. While other international partners also supported the NERC, UNMEER was a major underwriter, after the British. With funding from the Ebola Response Multi-Partner Trust Fund, UNMEER paid the salaries of 32 core staff of the NERC and supported critical Ebola response surges at various times with more than $550 000 from the Trust Fund [18].

(a). Structure

When it was established, the NERC was manned by British military and civilian members of the CJIATF, the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces (RSLAF) and the CEO's advisors. Additional personnel were recruited as the NERC developed. Several key management positions were filled by Sierra Leonean diaspora. The other main international partners were the UN, represented by UNMEER, and the WHO and the CDC. While several organizations were involved in the NERC, many interviewees said a triumvirate of the CEO, the British and UNMEER were dominant in its leadership. This was reflected in the fact that when the CEO had meetings with the President on a Wednesday, he took the British and UNMEER leads with him. The Tony Blair Africa Governance Initiative (AGI) and the British military were widely credited with being the backbone of the support for the NERC. The President was very much involved in setting the strategic direction of the response, interviewees said.

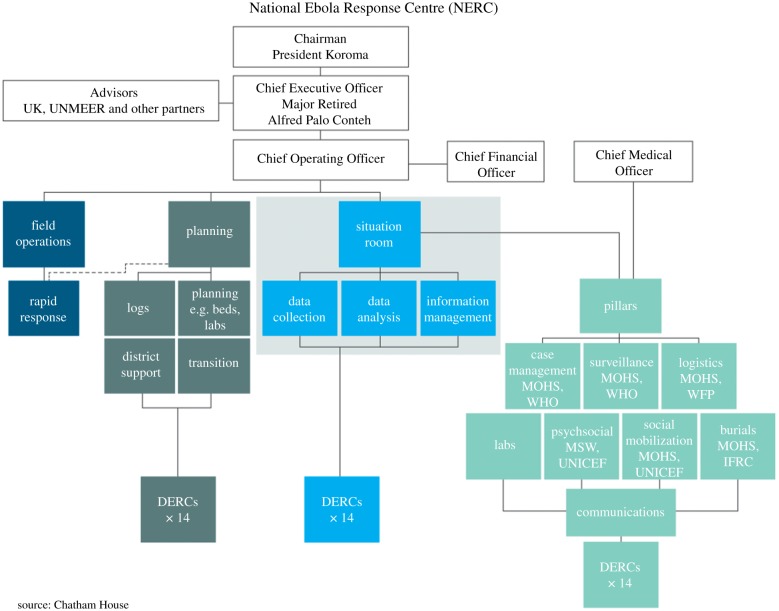

The organizational chart illustrating the structure of the NERC was constantly changing, with functions being added and dropped and the hierarchy and reporting lines shifting as changes were made to reflect operational innovations and needs. Figure 1 shows a conceptual organogram illustrating the set-up of the NERC by early 2015.

Figure 1.

Conceptual organogram illustrating the set-up of the NERC.

The NERC's development was an evolution. The first element to be established was the Situation Room, the engine of the NERC whose core function was to collect and analyse real-time data and inform decision-making. MOHS and RSLAF staff assigned to it were paired with an international—usually from the WHO, CDC or British military. An advisor from AGI was also among the staff, and the police and ONS were also represented, as well as UNMEER and OCHA.

The NERC then expanded to other functions. Another main operational unit was the planning directorate, which was responsible for, among other aspects, national strategy creation and review, planning for national campaigns and asset management, distribution and tracking. A third operational arm, the field operations directorate, consisted of the rapid response team charged with delivering the NERC's operational support.

The NERC absorbed the technical pillars that had been used by the EOC and reconfigured them as the needs changed. The technical component of the response, through these pillars, remained the domain of the MOHS, which led each pillar, with the support of a UN agency. The pillar leads were tasked with providing technical guidance for the response, including developing evidence-based standard operating procedures, setting policy around the technical interventions of the response, coordinating the work of the pillars in the districts, mobilizing the assets for their pillars and providing analysis to the NERC on the public health situation on the ground.

(b). Coordination

Early in its life, the NERC held morning and evening briefings that more than 100 people would attend. These were soon cut back to a single briefing in the evening, and the morning meeting was replaced with two rotating smaller management coordination meetings. One was for the Sierra Leonean leadership of the NERC only (the command group). The other, called the co-ord meeting, comprised the command group plus the major international stakeholders in the NERC—the UK team, UNMEER, WHO, and later CDC and UNICEF. Interviewees said USAID later joined. Specific NGOs would be invited to the co-ord meeting when necessary.

The NERC had crucial convening power. The co-ord meeting, which convened three times a week, became the most critical coordination session in the NERC, where differences regarding policy and strategy could be discussed and decisions made.

In another coordination layer, the technical pillars coordinated among themselves through a system called the Inter-pillar Action and Coordination Team (iPACT). The pillars reported on a rotational basis into the co-ord group meeting.

(c). Challenges

Interviewees said the NERC had its functional challenges.

(i). Data

One of the reasons for the founding of the NERC was that data from the MOHS and the WHO were inconsistent and unreliable. Getting data from the field was a major challenge for the first two or three months. The formal reporting line from the districts to the NERC did not work systematically, and asset tracking was ‘a nightmare,’ interviewees said. They added that data sharing was also a challenge that affected the credibility of the NERC's data early on, but that by the end of January 2015 data collection was sufficiently harmonized, which was a major win for the NERC.

(ii). Financial agility

Timely dispensing of funds from the NERC was also a challenge, and depended to some degree on which donor or other source the money was coming from. The lack of agility, due in part to bureaucracy and auditing requirements, was a source of frustration for many, who said that it hampered the response. One interviewee said that the World Bank and African Development Bank were particularly responsive to the problem from December 2014 and the NERC was able to unlock surge funding fairly quickly. Others said timely disbursement remained a problem throughout the response.

(iii). Coordination of partners

Another challenge was that each partner had its own strategy and those were not always in alignment with the NERC's plans.

Meanwhile, the British had their own evening meeting at their headquarters outside the NERC and were often dealing directly with the districts for the first few months of the NERCs life. This seemed to have been a significant source of tension.

The coordination of partners was a big problem. You start to understand why the British went direct to the DERCs. Things did get stuck. That shortened the timeframe of getting to the front line, but the problem is that (this) tended to happen where the relationship with the district coordinator was good, so the district response was uneven. It also meant that because the DERCs were getting what they needed directly from the British, they didn't feel they needed to cooperate with the NERC. This all slowed down getting on top of the outbreak.

Another interviewee was more condemning:

This didn't just slow things down. It completely altered the shape of the response in line with how they thought it should go, ignoring the host nation machinery that was supposed to be the coordination mechanism that everybody bought into.

(iv). Tensions in the NERC

Interviewees agreed there were several tensions that got in the way of the NERC working as well as it might have done, and said several partners could have leaned in to the NERC more.

You had different organizations deciding where they thought the priorities were. They said you can have a bit of our people, you can have a bit of our resource, but we're going to control the rest and do those things our way. I thought that was wrong. This half-way thing creates huge rifts.

Part of the challenge was the sheer diversity of responders, with their assorted backgrounds and agendas. There were cultural differences between military and civilian responders, but there were also different approaches within the civilian community, for example, between those who normally work in development and those who work on humanitarian emergencies, and sometimes there was a resistance to adapting.

Interviewees said diplomats from the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) played an important role in pulling political levers to effect UK influence in the NERC and mediate between the NERC and other stakeholders—from the Sierra Leonean government and the Americans to the CJIATF itself—and that this role was probably the most sensitively placed and quietly effective in the NERC.

Two main tensions within the NERC were the relationship between the MOHS and the NERC leadership, and the relationship between the British and some of the senior staff in the NERC.

(d). Tensions between the MOHS and NERC

Several interviewees said a major friction in the response was between the NERC and the leadership in the MOHS, adding that senior MOHS staff were embittered over their disenfranchisement, did not engage as much as they should have early on and then started to ‘land grab’ as the response started to tail off.

In first week of November (2014), none of the Ministry people would attend the NERC meetings. There were empty seats for two or three weeks, until the President ordered them to go. Then they came, but wouldn't engage. This went on for months.

Another interviewee said the MOHS were frequently a stumbling block in the first month or so of the NERC's life, for instance, shutting hospitals, removing equipment or sacking staff. A UK military source said:

‘They were actively working against us. They were very disruptive and the aim was to have the power back to run the Ebola response and we couldn't allow that.’

MOHS engagement with the NERC improved for the most part as the response continued, and engagement at the pillar lead level was not really an issue, interviewees said. However, they added, tensions remained. For instance, after the President announced in early September 2015 an extension of the NERC's lifespan, reportedly not a single district medical officer turned up to the district planning meeting that followed.

(e). Tensions between the British team and the NERC

Initial tensions between the British and some of the Sierra Leonean leadership within the NERC over control of the response were widely acknowledged and several interviewees said they got quite unpleasant at some stages, particularly as the NERC started to assert some autonomy towards the end of 2014. The NERC was not wholly dependent on UK funds, with UN, World Bank and some other donor funding also at its disposal. But many of the key NGOs implementing the response in the districts were funded by the UK.

‘The British were stage-managing everything,’ one interviewee said, describing a meeting that took place in December 2014 between NERC leaders and the UK team. ‘The agenda was what they want out of the NERC. The conversation was how the NERC was getting too big for its boots. The NERC leadership was getting more independent and they (the British) were complaining about a sense of not being in control.’

Several interviewees said they believed the UK team did not get fully behind the NERC for some time, with some contending that although they set it up and were closely involved in running it, the British at times undermined the NERC's authority.

Some said the tensions in the early days were caused by British frustration over what they felt was a lack of urgency and focus in the NERC that the British responders embedded in the structure could not accept. The British would often identify an issue, raise it in the NERC and then act when the NERC did not act responsively, interviewees said.

Many explained the dynamic as the UK filling a vacuum where it saw one, with one interviewee saying that although the NERC was theoretically the right construct, its staff struggled to make it function at first and British credibility was on the line. Others said that where people showed leadership, the British tucked in behind them and that the aim was always to get the Sierra Leoneans to run the NERC, but that it was sometimes necessary to step in.

However, many UK interviewees acknowledged that the British could have supported the NERC more once the outbreak began to decline. One interviewee said:

'We had operational decisions to make and the NERC wasn't in a state in that early period. People would forgive us for the initial period because everyone understood what a mess it was. The bit that annoys people is the fact that once the NERC was established, we did not lean into it in a way that would allow it to succeed. Maybe that parallel system got a bit entrenched; I think we got it to a point in December (2014) where we should have been doing a lot more empowering of the Sierra Leoneans.'

Another source said the dynamic between the British and the Sierra Leoneans in the NERC was largely a function of the context at any given time.

At the beginning, the UK were very scared, not trusting the government. What do you do? Sometimes you push them aside and then as time goes by, you develop a bit more confidence, you find local partners who are more credible. Maybe you take out one or two more of your hawkish people and you put in a few more partnership-oriented people and then the relationship changes and it evolves, becomes more mature.

Several interviewees said the relationship between the NERC and the British started to become much more collaborative in March 2015 and that tensions started to ease when the CJIATF began to get more behind the NERC. Some interviewees said that following the fall in infection rates across the country, the plan was to try to make the NERC more effective so that British staff could be withdrawn within months and the operation could be run independently by the Sierra Leoneans.

It is unclear to what extent this shift in the relationship was attributable to personalities and their attitudes and engagement styles, to issues being worked out over time and the NERC's capacity strengthening, or to a change in what was called for at that stage of the outbreak. One British interviewee said:

‘There were things you could have driven without them, faster, but in terms of the relationship issue, there were only UK DERCs left and we were heading for trouble, as the NERC was focused on the same districts. There was potential for loads of conflict and it wouldn't work if we weren't pulling together.’

More UK staff were put into the NERC and UK's separate headquarters briefings were phased out so that all coordination was funnelled through the NERC.

‘There has been a huge shift,’ a Sierra Leonean interviewee said in September 2015. ‘Before this, senior Sierra Leonean personalities at that NERC didn't feel ownership of the response. They thought it was a British response. They sat back, didn't innovate. They have since shown they are capable of more.’

6. The DERCs: October 2014–December 2015

(a). Origin of the DERCs

In September 2014, the backlog of burials was considered the major bottleneck and risk in the response (unpublished UK military report). There were bodies piling up in the streets of Freetown.

The burial vehicle teams in the Western Area, which includes the capital and its outskirts and was a hotspot of the outbreak, were not setting out to pick-up bodies until about 13.00 h because it would take them half a day to get the vehicles ready.

The CJIATF tasked a UK army colonel to carry out a review of how this could be improved. On 19 October 2014, he, a staffer from AGI and others set up a command centre. Burial teams would bring their vehicles in every evening to the RSLAF base, where they were washed, repaired, refuelled and restocked overnight and positioned in strategic locations around the capital in time for them to take them out at 08.00 h. IFRC and the NGO Concern were recruited to manage the new system after they were trained in the process. The command centre was essentially a breakaway from the MOHS-led district response, establishing a command and control mechanism at a new location, the British Council.

Within 3 or 4 days they had cleared the backlog. Within a week, more than 80% of bodies in the Western Area were being buried within 24 h, and within two weeks, that rose to 95%, and eventually 100%.

Days later, the President ordered all Ebola functions in the district moved to the new command centre, which soon expanded to other interventions. The system was built in blocks, according to the most urgent priorities, and NGO partners were recruited to manage them.

The success was a proof of concept for the efficiencies that command and control could bring and was a turning point in the response. It was recognized that coherence and coordination were required not only at the national but also the district level, with public health messaging and behaviour influence reaching into the villages. Over a period of about six weeks, DERCs modelled on the Western Area command centre were established in all 14 districts, with UK support staff embedded in the eight districts where the outbreak was worst.

(b). Structure of the DERCs

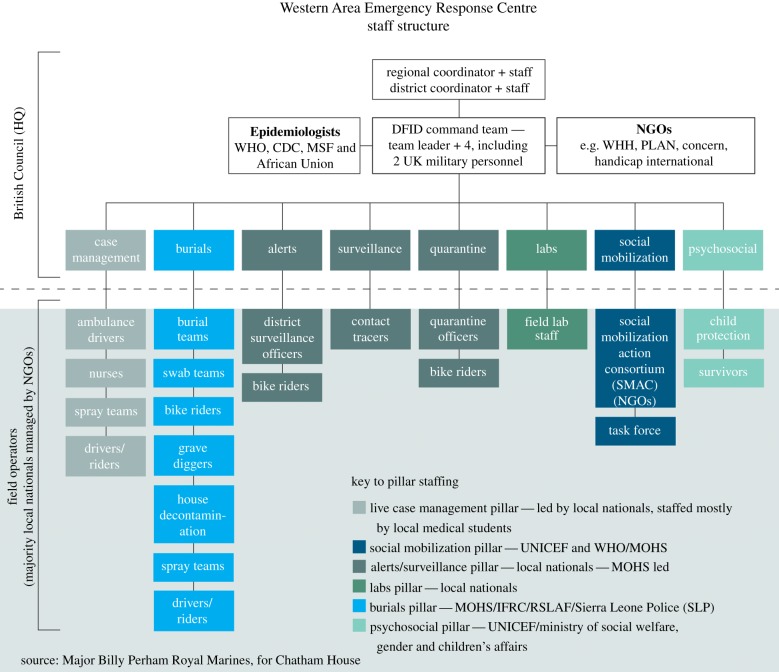

The idea was to bring planning, operations, logistics, finance and administration together into one place, as a district-level equivalent of the NERC. Each DERC was different, as they were designed to be adaptable to local needs. Figure 2 shows how the Western Area Emergency Response Centre, the DERC for that district, was configured.

Figure 2.

Configuration of the Western Area Ebola Response Centre, the DERC for the outskirts of Freetown. Copyright owned by Chatham House.

DERCs were theoretically co-headed by a politically appointed Sierra Leonean district coordinator (DC) and the district medical officer (DMO). In addition, each of the British-supported DERCs initially had a UK military staffer, and by January 2015, District Ebola Support Teams (DESTs) blistered onto them to help run operations. UNMEER also embedded a field crisis manager in each DERC. These elements comprised the bulk of the operational arm of the DERCs. The DEST comprised a mix of usually five or six UK military and civilian personnel. The head of the DEST was a DFID civil servant or contractor and the chief of staff was a UK military staffer. The UK deployed 80 people in the DERCs at the peak of the outbreak (unpublished UK government report).

Each of the other DERCs, which were supported mainly by NGOs (as opposed to British supported), had an RSLAF chief of staff.

The dynamic between DCs and their UK support teams varied, and the extent to which the British team dominated the decision-making depended on the strength of the DC, interviewees said. While the operational decisions were in general made by the international partners, the DCs tended to take charge of the local interface, including engagement with community leaders. The disease control interventions were implemented through the pillars, which, as at the national level, were led by MOHS staff in partnership with a UN agency. At the district level, the pillar leads led implementation of the technical advice, guided strategic priorities, provided the medical response and addressed technical questions and developed recommendations. The epidemiology work was led by the WHO and CDC. NGOs were the main implementing partners and managed the frontline response workers, the vast majority of whom were Sierra Leonean. RSLAF staff ran the burials command and control.

(c). Challenges

The functionality of the DERCs was variable, with much depending on the quality of the relationship between the DC and the DMO, interviewees said.

(i). District Coordinator–District Medical Officer relationship

The tension between the MOHS and the NERC was replicated to varying degrees in the districts between the DCs and the DMOs.

The DMOs were supposed to have as much ownership of the response as the DCs, but initially it was difficult for them to get space at the table to give their opinion on the medical approach, interviewees said, adding that many of the DCs had political ambitions and saw the job as an opportunity for themselves, while the DMOs felt disenfranchised after the President took control of the response out of the Ministry's hands, and many disengaged.

The libretto that played out at the national level meant there was an inherent distrust between the (DCs) and the DMOs in most of the districts. Where both were reasonable people, they found a way to put it back together. But the starting condition was basically DERC and DMO are different entities. When it came to the surveillance and community mobilisation and doing case finding and contact tracing, that's when the medical officer became much more important and that's when the relationship had to be fixed.

One interviewee said that when the President put out a clear message that it was to be an equally-led response, it created the space for the DMOs to come back in. The WHO had by January 2015 brought its response up to scale and had become stronger at the district level, and helped to bring many of the DMOs back. That brought balance and made a substantive shift in the response between January and March 2015. The district response became much more technically led, with the operational capacity supporting the achievement of the technical objectives, the interviewee said.

However, tensions reportedly persisted in some areas, and in at least one DERC, the DMO remained disengaged, rarely visiting the DERC—a situation some said was preferable to having to contend with a combative relationship that hampered the response.

(ii). NGO coordination

Interviewees said it took some time for coordination across the DERC to work well, but added that in some districts, coordination of NGOs was a specific challenge. In those districts, several NGOs continued to operate outside the net of the DERC, and not in alignment with its strategy, interviewees said, adding that this meant that setting up services and maximizing resources did not always happen as they should and the ability of the DERC to build trust in the community was sometimes undermined.

Social mobilization was an area where coordination at the district level was particularly challenging, interviewees said, as it attracted a large proportion of the NGOs. The lack of coordination resulted in uneven coverage and in a sense that the NGOs were acting in competition with, rather than in support of, the DERC social mobilization pillar, interviewees said.

Interviewees said the British and UNMEER improved coordination of NGOs by placing more focus on it as the response matured, but that NGO coordination within the official structures was largely voluntary and not systematic.

District response managers reported different approaches. For instance, one said it was a non-negotiable requirement that the DERC was briefed in full on any new activities NGOs were undertaking, while another said that calling them to meetings to ensure their activities were in alignment with the district strategy was eventually successful. Other district response managers tackled the NGO coordination challenge by engaging with them one-on-one whenever they needed specific things to be done.

At the national level, the UNMEER NERC lead established a platform for NGOs to regularly plug into the strategic discussions, but for some reason, not all NGOs were consistent in using these platforms and although they were key implementers of the field response, they were not major players in running the operations side of the response.

7. Politics

Politics was a significant challenge. Interviewees said that in some areas of the country, it was impossible to dissociate oneself from the political environment. Political parties were jockeying for primacy at the district level and using the Ebola response to lever their own political ambitions, sources said. One interviewee said the amount of time that had to be spent on governance analysis and navigating the ‘riotous political battlefield’ meant that in one district, getting to zero Ebola cases took about two or three months longer than in other places.

Understanding the political landscape entailed deciphering the structure of district councils, the political networks and their role in blocking tactics and counter-messaging, and how their efforts were having a negative effect on communities' willingness to play into the response. One example of how party politics hampered the response was described by one interviewee thus:

(The) WHO had recruited all 25 members of the district council but didn't realise they were in an intra-political conflict within the APC (All People's Congress). This dated back to a point where the district councils were divested of development budget administration, particularly the health budget. In order to punish the APC party, and in particular the President, all 25 members of the district council, in their capacity having been recruited by WHO to be contact tracing supervisors, would simply drag their feet through treacle. They would see everything happening and they would do nothing to effect positive outcomes in contact tracing. These kinds of things were really railing against us and it took a bit of time to understand this.

The interviewee explained that in order to be effective it was necessary to engage in the politics, by applying political leverage in quiet circles, for instance with strategic CC'ing of emails to set in motion a process that resulted in Sierra Leoneans elevating problems through the national architecture and issues getting resolved. Once the UK responders understood the patron–client relationships, it became fairly easy to overcome the negative effects of the politics, in some cases by building the political capital of the DC to apply the right political levers to clear blockages. Once those who were blocking progress were neutralized, this opened the way for others, such as the traditional chiefs, to step into their role and the speed of transition to zero Ebola cases quickened.

UK responders were also sometimes able to diffuse the politics by taking pressure off Sierra Leoneans targeted by political manoeuvres, for instance by handling calls from politicians themselves.

8. Final transition: March–December 2015

In March 2015, with the number cases reported per-week down to double digits and the command and control systems firmly in place in the DERCs, the British decided to gradually scale back their presence in the response structures [19].

However, a new DFID head of the CJIATF had rotated in during this period and was not as convinced of the strategy, interviewees said

So there was this debate. Do we leave the military out in the districts and they can carry on running the show? Or do we bring the military in because they've done their job and we can now leave it to the Sierra Leoneans and the odd DFID person to run the response?

The withdrawal of military, and then civilian, personnel went ahead, with the UK military force dropping from about 700 to 250 (unpublished UK military report). By 12 May 2015, Sierra Leone had gone eight days without an Ebola case and the virus had been beaten back into three quarantined homes [20]. The Ebola treatment unit for infected healthcare workers had not seen a patient since the middle of March. The outlook was good.

But shortly thereafter, a woman left a quarantined house and went back to her home, causing a spike in cases. This prompted the British to put military personnel back into the DERCs in the remaining trouble spots and to put key people back into the NERC. Focus was put on building capacity and local ownership of the response, and many interviewees said rifts were healed during this last part of the response. The planning and execution of Operation Northern Push, a NERC initiative in June 2015, was cited as an example of the improved collaboration that characterized the later stage of the response. It was described as a watershed in making the response not only more refined but also more integrated, finally achieving true partnership between the NERC and international responders. UNMEER closed its mission on 31 July 2015 and its responsibilities were transferred to the WHO, although the UNMEER representative remained embedded in the NERC under a British-funded WHO contract to continue to coordinate the UN agencies, donors and NGOs. The British maintained their presence until Ebola transmission was stopped and the NERC and DERC retired.

The WHO declared Sierra Leone free of Ebola transmission for the first time on 7 November 2015 [21]. Following the declaration, the British began to wrap up their operation, sending the military home shortly thereafter. DFID remained until January 2016, after the NERC was closed. The NERC's responsibilities were divided among the ONS, the MOHS and the Ministry of Social Welfare, Gender and Children's Affairs, while the DERC's were absorbed by the District Management Health Teams [22].

9. Conclusion

From the establishment of the National Ebola task force in March 2014 to the closure of the NERC and DERCs on 31 December 2015, the operational architecture of Sierra Leone's response to the 2013–2016 outbreak went through three main iterations over the course of 22 months. The unusual duration of the outbreak meant that the response had longer than usual to hone itself and this provided a rare opportunity to study the management of a response that endured long enough to mature.

It was clear that while there were many bumps on the road to zero, the response mechanism became more refined over time and it seemed that it eventually found a balance. The final coordination structures were not created from some pre-defined best practice but evolved, driven by events on the ground, an amalgamation of ideas, and political and donor willingness.

A range of international partners provided critical support to the response. However, on behalf of the British government, which committed £427 million to the response in Sierra Leone, DFID overwhelmingly funded and supported a national response architecture that brought disparate actors and agencies together and enabled the containment and eventually the elimination of the virus [23].

The circumstances that enabled the British to take on such a significant coordination role were rare. Ebola is a disease that inspires extreme fear, and the scale of the outbreak was unprecedented. Meanwhile, the UK's extraordinary level of influence was born out of a strong and long-standing relationship with Sierra Leone, including close ties between the two militaries. And while a country can be overwhelmed by an outbreak, a situation where the WHO fails to help a government to take control of it is unusual. The WHO wasn't able to provide the needed coordination during the window of opportunity before the outbreak spiralled out of control, an OCHA-led UN cluster system was not brought in to fill the gap, and then UNMEER—created as an alternative UN mechanism—did not fulfil that function either.

It was a rare convergence of factors that is unlikely to be replicated and care should be taken not to generalize the applicability of the approach taken in Sierra Leone to future health crises.

Nevertheless, the experience provides some insights that might be useful for future crises. Decentralization of the response appeared to be important for the level of agility and tailoring necessary. While coordination and collaboration in the DERCs was difficult, in part because of the turnover in personnel and the sheer volume of organizations in the districts, interviewees said the provision of a focal point for partners to work through in the field was one of the DERCs' most important contributions. And despite the challenges, several interviewees saw the DERCs, through which the targeted population behaviour change campaign was delivered, as one of the biggest strategic successes of the response in Sierra Leone and a key ‘battle winner.’

Most interviewees judged the NERC to have been a qualified success, considering that it was staffed by a team of people who were never trained to work together, all reporting to different people and coming with different agendas. The UK acting in parallel with the NERC in the first few months did seem to have adverse consequences for key relationships, but the net impact on the outcome of the response is difficult to ascertain. And despite those and other tensions, partners largely converged around the NERC, it had data, it responded to what it was seeing and by and large the response was funnelled through it.

The problems were complex, and policy and strategy were being constructed as they went along. The players were many, and most of them had no experience of epidemic response, let alone an Ebola response. Regardless of the systems and management structures that were put in place, it seemed that at nearly every level, personalities and personal relationships appeared to be key to the functioning of the response.

The response was not integrated under a single command, but it was to a certain degree coordinated, and coordination tightened up as the response matured. It seems the Sierra Leoneans did not really have the power to impose a joint managerial mechanism, but that is reflective of the way humanitarian response tends to operate. It can be argued that a well-coordinated response is more functional than a badly integrated one and that in an emergency, the energy required to gain complete command and control over the whole process can often be better expended in sharpening coordination.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Philip K. Angelides, Research Assistant at Chatham House at the time the research was undertaken, and Gita Honwana Welch, Associate Fellow with the Africa Programme of Chatham House, for their valuable contributions to the research in Sierra Leone.

Competing interests

I have no competing interests.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the Rockefeller Foundation and the Chatham House Director's Research Innovation Fund.

References

- 1.Ross E, Honwana Welch G, Angelides P. 2017 Sierra Leone’s response to the Ebola outbreak: management strategies and key responder experiences. Research Paper, London: Royal Institute of International Affairs. See https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/sierra-leones-response-ebola-outbreak-management-strategies-key-responder . ISBN: 978-1-78413-205-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department for International Development (DFID). 2016. DFID's response to the crisis. Ebola: responses to a public health emergency. London, UK: DFID. (http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmintdev/338/33805.htm) (accessed 8 July 2016).

- 3.DuBois M, Wake C, Sturridge S, Bennett C.2015. The Ebola response in West Africa. Humanitarian Policy Group. HPG Working Paper. (http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9903.pdf. ) (accessed 22 February 2016).

- 4.Médecins Sans Frontières. 2015. An unprecedented year: doctors without borders. Médecins Sans Frontières' response to the largest ever Ebola outbreak. See https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/sites/usa/files/ebola_accountability_report_us_version_7-8-15.pdf (accessed 25 August 2016).

- 5.Republic of Sierra Leone. 2014. National Communication Strategy for Ebola response in Sierra Leone. (http://ebolacommunicationnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/National-Ebola-Communication-Strategy_FINAL.pdf) (accessed 21 July 2016).

- 6.World Health Organization. 2014. Ebola virus disease, West Africa (Update of 26 May 2014). (http://www.afro.who.int/en/clusters-a-programmes/dpc/epidemic-a-pandemic-alert-and-response/4143-ebola-virus-disease-west-africa-26-may-2014.html) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 7.Republic of Sierra Leone. 2014. National Communication Strategy for Ebola response in Sierra Leone. (See http://ebolacommunicationnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/National-Ebola-Communication-Strategy_FINAL.pdf) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 8.Profile: Leading Ebola doctor Sheik Umar Khan. 2014. BBC News, 30 July 2014. (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-28560507) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 9.The Republic of Sierra Leone. 2014. Address to the Nation on the Ebola Outbreak by His Excellency The President Dr. Ernest Bai Koroma July 30, 2014. (http://www.statehouse.gov.sl/index.php/useful-links/925-address-to-the-nation-on-the-ebola-outbreak-by-his-excellency-the-president-dr-ernest-bai-koroma-july-30-2014) (accessed 21 July 2016).

- 10.World Health Organization Sierra Leone. 2016. President Koroma makes second visit to the Ebola Emergency Operations Centre at the WHO Country Office. (http://www.afro.who.int/en/sierra-leone/press-materials/item/6882-president-koroma-makes-second-visit-to-the-ebola-emergency-operations-centre-at-the-who-country-office.html) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 11.Thomas A.2014. Health minister Miatta Kargbo sacked. Sierra Leone Telegraph, 29 August 2014. (http://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/?p=7208. ) (accessed 22 July 2016).

- 12.The Republic of Sierra Leone. 2014. Office of The President Press Release. (http://www.statehouse.gov.sl/index.php/useful-links/968-office-of-the-president-press-release) (accessed 22 July 2014).

- 13.Global Ebola Response. 2016. UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response. (http://ebolaresponse.un.org/un-mission-ebola-emergency-response-unmeer) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 14.UN News Centre. 2014. UN announces mission to combat Ebola, declares outbreak ‘threat to peace and security’. (http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=48746#.WB9ck-GLT_Q) (accessed 6 November 2016).

- 15.Department for International Development (DFID). 2016. Written evidence submitted by the Department for International Development (DFID). Ebola responses to a public health emergency. London, UK: DFID. (http://data.parliament.uk/WrittenEvidence/CommitteeEvidence.svc/EvidenceDocument/International%20Development/Ebola%20Responses%20to%20a%20public%20health%20emergency/written/21667.html) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 16.The Republic of Sierra Leone. 2014. Press release. (http://www.statehouse.gov.sl/index.php/press-release/1019--press-release) (accessed 1 August 2016).

- 17.Olu O, et al. 2017. Incident management systems are essential for effective coordination of large disease outbreaks: perspectives from the coordination of the Ebola outbreak response in Sierra Leone. Frontiers in Public Health. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5117105/) (accessed 9 January 2017).

- 18.Global Ebola Response, Sierra Leone. 2016. (http://ebolaresponse.un.org/sierra-leone) (accessed 1 November 2016).

- 19.World Health Organization. 2016. Ebola data and statistics: data published on 11 May 2016. Graph of new confirmed EPI cases per week for Sierra Leone. (http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.ebola-sitrep.ebola-country-SLE-20160511-graph?lang=en) (accessed 5 August 2016).

- 20.World Health Organization. 2015. Ebola Situation Report—13 May 2015. (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/170508/1/roadmapsitrep_13May15_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1&ua=1) (accessed 1 August 2016).

- 21.World Health Organization. 2016. Latest Ebola outbreak over in Liberia; West Africa is at zero, but new flare-ups are likely to occur. (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/ebola-zero-liberia/en/) (accessed 6 June 2016).

- 22.Foryoh P. 2016. Sierra Leone: mandate of National Ebola Response Centre ends—official. Makoni Times, 4 January 2016. See http://makonitimes.com/2016/01/04/sierra-leone-mandate-of-national-ebola-response-centre-ends-official/ (accessed 1 August 2016).

- 23.Department for International Development (DFID). 2015. Oral statement to Parliament. An update on the UK’s response in West Africa. London, UK: DFID. (https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/ebola-outbreak-an-update-on-the-uks-response-in-west-africa) (accessed 9 November 2016).