Abstract

Background and aims

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) permits effective identification of diffuse CAD and atherosclerotic plaque characteristics (APCs). We sought to examine the usefulness of diffuse CAD beyond luminal narrowing and APCs by CCTA for detecting vessel-specific ischemia.

Methods

407 vessels (n=252 patients) from DeFACTO diagnostic accuracy study were retrospectively analyzed for percent plaque diffuseness (PD). Percent plaque diffuseness (PD) was obtained on per-vessel level by summation of all contiguous lesion lengths and divided by total vessel length, and was logarithmically transformed (log percent PD). Additional CCTA measures of stenosis severity including minimal lumen diameter (MLD), and APCs such as positive remodeling (PR) and low attenuation plaque (LAP) were also included. Vessel-specific ischemia was defined as fractional flow reserve (FFR) ≤0.80. Multivariable regression, discrimination by area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and category-free net reclassification improvement (cNRI) were assessed.

Results

Backward stepwise logistic regression revealed that for every unit increase in log percent PD, there was a 58% (95% CI: 1.01–2.48, p =0.048) rise in the odds of having an abnormal FFR, independent of stenosis severity and APCs. The AUC indicated no further improvement in discriminatory ability after adding log percent PD to the final parsimonious model of MLD, PR, and LAP (AUC difference: 0.003, 95% CI: −0.003–0.010, p =0.33). Conversely, adding log percent PD to the base model of MLD, PR, and LAP improved cNRI by 0.21 (95% CI: 0.01–0.41, p <0.001).

Conclusions

Accounting for diffuse CAD may help improve the accuracy of CCTA for detecting vessel-specific ischemia.

Keywords: Coronary computed tomography angiography, diffuse coronary artery disease, atherosclerotic plaque characteristics, stenosis severity, fractional flow reserve

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) affects more than 16 million adults in the United States, and is the most prominent cause of death among men and women (1). The gold standard for evaluating the hemodynamic significance of coronary stenoses is invasively determined fractional flow reserve (FFR). However, abnormal FFR values in the absence of focal epicardial disease are not uncommon, and have been observed in 18% of coronary arteries (2). Notably, diffuse CAD, which is underestimated by luminal evaluation with invasive coronary angiography (ICA), increases risk of mortality (3,4).

Further enhancements in cardiac imaging modalities have led to the emergence of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), a relatively novel and promising imaging technique for detection and assessment of coronary luminal narrowing and high-risk atherosclerotic plaque characteristics (APCs) that include positive remodeling (PR), low attenuation plaque (LAP), and spotty calcification (SC) (5). In contrast to invasive angiography, CCTA goes beyond coronary “luminology” by directly visualizing coronary plaques located at the vessel wall. In spite of this, however, the impact of CCTA-evaluated plaque diffuseness (PD) beyond conventionally available CCTA measures of CAD severity and APCs has not been determined to date. Using data from a prospective international multicenter study, we therefore set out to examine the usefulness of percent PD above and beyond luminal narrowing and other measures of atherosclerotic plaque by CCTA for detection of vessel-specific ischemia.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study population

The DeFACTO (Determination of Fractional Flow Reserve by Anatomic Computed Tomographic Angiography) Study is a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional diagnostic accuracy study performed at 17 centers in 5 countries including Canada, Belgium, Latvia, South Korea, and United States. The rationale and design of the DeFACTO study has been previously described (6). Enrolled patients included adults with suspected CAD who underwent both clinically indicated non-emergent CCTA and ICA. Patients were not deemed eligible for study inclusion if they had a prior history of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with suspected in-stent restenosis based upon CCTA findings, and suspicion of/or recent acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Further details regarding exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere (6). Hence, the current analyses included 407 vessels derived from 252 consecutive stable patients, wherein percent PD was retrospectively measured. The institutional review boards at all participating centers approved the study protocol, and further details of the trial are registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (Registration #: NCT01233518).

2.2. Image acquisition and analysis for ICA

ICA with intended FFR were performed within 60 days of CCTA. No events occurred between CCTA and the invasive procedures. Selective ICA was performed by standard catheterization in accordance with the American College of Cardiology guidelines for coronary angiography (7). FFR was performed at the time of ICA (PressureWire Certus, St. Jude Medical Systems, St. Paul, Minnesota; ComboWire, Volcano Corp, San Diego, California) in vessels deemed clinically indicated for evaluation and demonstrating a stenosis between 30% and 90%. After administration of intracoronary nitroglycerin, a pressure-monitoring guide wire was inserted distal to a stenosis. Hyperemia was induced with intravenous (140 μg/kg/min) administration of adenosine. FFR was calculated by dividing the mean distal coronary pressure by the mean aortic pressure during hyperemia. In accordance with prior studies, a FFR ≤0.80 was considered indicative of vessel-specific ischemia (8).

2.3. Image acquisition and analysis for CCTA

CT-based coronary angiography was performed using 64– or higher detector row scanners in accordance with the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) guidelines (9,10). An intravenous contrast agent (approximately 80 to 100 ml), followed by saline (50 to 80 ml), was injected at a flow rate of 5 ml/s. The scan parameters included heart-rate dependent pitch (0.20 to 0.45), 330 ms gantry rotation time, 100-kVp or 120-kVp tube voltages, and 350-to-800 mA tube current. Radiation dose reduction strategies were employed when feasible. Radiation dose for CCTA was determined using the dose-length product with an organ-specific conversion factor k of 0.014 mSv/mGy/cm (11). Transaxial images were reconstructed with 0.5- to 0.75-mm slice thickness, 0.3-mm slice increment, 160- to 250-mm field of view, 512 × 512 matrix, and a standard kernel. All CCTAs were interpreted in an intention-to-diagnose approach. CCTA was analyzed using a dedicated 3-dimensional workstation (Ziosoft, Redwood City, California; Advantage AW Workstation, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) by independent level III experienced readers in a blinded fashion.

All CCTAs were evaluated by an array of post-processing techniques, as previously described elsewhere (5). Coronary arteries and branches were categorized into 1 of 3 vascular territories: left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD), left circumflex coronary artery (LCX), and right coronary artery (RCA). The left main coronary artery and diagonal branches were considered part of the LAD, while the obtuse marginal branches were assigned to the LCX in our analysis. The posterior descending artery was considered part of either the RCA or LCX system, depending upon the coronary artery dominance. Stenosis severity was graded in accordance with SCCT guidelines, and categorized as 0%, 1% to 24%, 25% to 49%, 50% to 69%, and ≥70%.

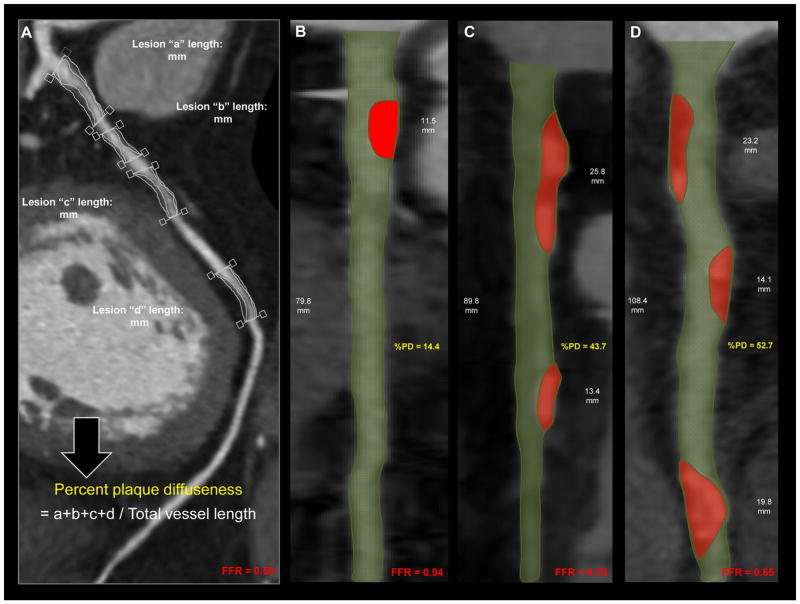

The individual lesion length in the coronary artery was measured as the length of the significantly narrowed segment from the proximal to the distal end of an individual lesion in the multiplanar reformat images. Total lesion length was obtained by summation of all lesion lengths in the coronary artery (Fig. 1). Percent PD was then calculated by total lesion length divided by the total vessel length. Percent PD was therefore obtained on a per-vessel level regardless of the number of lesions. Hence, a single value of percent PD for individual vessel was utilized in this study and a single FFR measurement was performed by investigators on a per-vessel level in vessels with significant ischemia that were deemed clinically indicated for evaluation. Diameter stenosis (%) and area stenosis (%) were calculated using proximal and distal reference segments, which were selected to be the most adjacent points to the maximal stenosis in which there was minimal or no plaque. Minimal lumen diameter (MLD) and minimal lumen area (MLA) were measured from the long-axis and short-axis views of double-oblique reconstructions at the site of the maximal stenosis, respectively. Longitudinal inner lumen and outer vessel wall contours were detected using an automatic algorithm. However, manual editing was performed for both inner lumen and outer vessel wall delineations, wherever needed. As previously described, non-evaluable CCTAs with poor scan quality were excluded from this study and the scan quality was excellent to good in the majority of patients (6).

Fig. 1. Measurements of plaque diffuseness (PD).

(A) Multiplanar reformat of the CCTA demonstrating four individual lesions (a, b, c, and d) with proximal and distal reference in the left anterior descending artery. Percent PD was obtained by summation of all contiguous lesion lengths and divided by total vessel length of each respective coronary artery. (B, C, and D) Multiplanar reformats of the CCTA assessing percent PD in the left anterior descending arteries with 1- and 2- diseased segments (B and C), and in the right coronary artery with 3- diseased segments (D). The corresponding percent PD and fractional flow reserve values are also displayed. %PD, percent plaque diffuseness; FFR, fractional flow reserve.

Percent aggregate plaque volume (percent APV) was calculated as previously described (12). Briefly, plaque area was computed as the vessel area minus the lumen area of each cross section. APV was then obtained by summation of all contiguous plaque areas in the coronary artery from the proximal to the distal end of an individual lesion in a vessel. Percent APV was calculated as: APV divided by the sum of vessel volume from the proximal to the distal end of an individual lesion in a vessel.

Qualitative coronary APCs including positive remodeling (PR), low attenuation plaque (LAP), and spotty calcification (SC) were evaluated for coronary vessels directly interrogated by invasive FFR. These coronary APCs are also referred to as high-risk plaque (HRP) characteristics (13,14). A remodeling index was defined as a maximal lesion vessel diameter divided by proximal reference vessel diameter, with PR defined as a remodeling index >1.10. LAP was defined as any voxel <30 Hounsfield units within a coronary plaque. SC was defined by an intralesion calcific plaque <3 mm in length that comprised <90° of the lesion circumference. Quantitative coronary atherosclerotic plaque analysis was performed using semi-automated plaque analysis software (QAngio CT Research Edition v2.02, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands).

2.4. Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted on a per-vessel basis. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution. Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean ± SD, whereas non-normally distributed variables are reported as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables are reported as counts with proportions. Percent PD was found to be non-normally distributed and was therefore logarithmically transformed (log percent PD). p-values were obtained by use of Student’s t test for continuous measures, and by Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical measures. FFR parameters were recorded on a continuous scale and dichotomized at a threshold of 0.80, with values ≤0.80 considered hemodynamically significant and indicative of vessel-specific ischemia.

First, univariable linear regression was employed to examine the continuous relationship of each CCTA parameter (i.e., log percent PD, diameter stenosis, area stenosis, MLA, MLD, percent APV, and APCs including PR, LAP, and SC) with vessel-specific ischemia by FFR. The linear regression was reported as unstandardized coefficients (B) and standard error (SE). The relationship of each individual CCTA parameter and the likelihood of having an abnormal FFR were further examined by use of univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression models reporting odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Backward stepwise logistic regression was performed to examine the potential relationship of each CCTA parameter with vessel-specific ischemia. In order to account for within-patient correlation, a mixed effects regression model was employed. In addition, as a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the logistic regression model after excluding the vessels with prior PCI, in an effort to test the robustness of log percent PD over stenosis severity and APC evaluation alone. Further still, a sensitivity analysis was also performed with percent APV pushed into the logistic regression model, to examine the relationship of log percent PD over percent APV and other measures of atherosclerotic plaque.

Second, a global Chi-square test was employed to assess model fit, whereby log percent PD added to the most suitable covariates retained from backwards logistic regression was compared against the retained covariates alone. Third, area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) were fashioned using the method described by DeLong et al. and a C-statistic was calculated to determine the incremental discriminatory ability of log percent PD over stenosis severity and APC evaluation alone (15). Fourth, reclassification of vessel-specific ischemia was determined using category-free net reclassification improvement (NRI) indices based on log percent PD added to the other retained CCTA parameters from the final adjusted model (16). Finally, the Youden Index was used to define the optimal threshold value for percent PD. The sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), and positive predictive value (PPV) were calculated according to the optimal threshold value for percent PD in order to identify vessel-specific ischemia. Statistical tests were two-tailed and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). The schematic representation of the study design is depicted in the Supplementary Fig. 1.

The inter-observer and intra-observer variability of our core laboratory has been previously described and validated as compared to intravascular ultrasound (17).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

Baseline characteristics of the study sample are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 63 ± 8.7 years and 71% (n=178) were male. The study population was predominantly Caucasian (n=169, 67%), and there was a substantially high prevalence of certain CAD risk factors including hyperlipidemia (80%) and hypertension (71%). Of the study sample, the number of patients who experienced a previous MI (n=15, 6%) or previous PCI (n=16, 6%) was relatively low. The mean coronary artery calcium score (CACS) was reported as 381.5 Agatston units in 218 patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Overall (n=252) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 62.9 ± 8.7 |

| Male, n (%) | 178 (70.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.8 ± 3.8 |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 169 (67.1) |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 (21.2) |

| Hypertension | 178 (71.2) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 201 (79.8) |

| Current smoker | 44 (17.5) |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 50 (19.9) |

| Angina pectoris, n (%) | 193 (77.2) |

| Typical, n (%) | 128 (51.2) |

| Atypical, n (%) | 56 (22.4) |

| Non-cardiac, n (%) | 2 (0.8) |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 7 (2.8) |

| Asymptomatic, n (%) | 57 (22.8) |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 15 (6.0) |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 16 (6.4) |

| Coronary artery calcium score, Agatston units, mean (SD)a | 381.5 (401.0) |

Available in 218 patients.

SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Vessel characteristics and FFR

The vessel characteristics derived from CCTA according to FFR are listed in Table 2. Foremost, significant differences were observed for each CCTA parameter (all p <0.001) after comparing groups based on FFR values >0.80 versus values ≤0.80. Notably, percent PD was significantly higher in ischemic vessels as compared with non-ischemic vessels (e.g., 30.2, IQR: 21.0–41.8 versus 21.0, IQR: 13.0–31.3, p <0.001).

Table 2.

Vessel characteristics by coronary computed tomography angiography as a function of FFR values.

| Per-vessel analysis (n=407) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| FFR >0.80 (N=256) | FFR ≤0.80 (N=151) | p-value | |

| Diffuseness measures: | |||

| Total lesion length, mm | 23.1±14.6 | 55.3±9.7 | <0.001 |

| Number of lesions | 0.09 | ||

| 1 | 200 (78.1) | 104 (68.9) | |

| 2 | 49 (19.1) | 39 (25.8) | |

| 3 | 7 (2.7) | 8 (5.3) | |

| % PD, median (IQR) | 21.0 (13.0–31.3) | 30.2 (21.0–41.8) | <0.001 |

| Number of diseased segments | 0.18 | ||

| 1 | 207 (80.9) | 111 (73.5) | |

| 2 | 45 (17.6) | 35 (23.2) | |

| 3 | 4 (1.6) | 5 (3.3) | |

| Other CCTA measures: | |||

| Diameter stenosis, % | 36.3±13.0 | 47.6±13.1 | <0.001 |

| Area stenosis, % | 57.8±16.7 | 70.9±13.7 | <0.001 |

| Minimal lumen diameter, mm | 2.0±0.5 | 1.5±0.4 | <0.001 |

| Minimal lumen area, mm2 | 3.3±1.7 | 2.0±1.0 | <0.001 |

| % APV, mean ± SD | 55.3±9.7 | 62.2±8.8 | <0.001 |

| PR | 72 (28.1) | 121 (80.1) | <0.001 |

| LAP | 24 (9.4) | 66 (43.7) | <0.001 |

| SC | 26 (10.2) | 42 (27.8) | <0.001 |

FFR, fractional flow reserve; % PD, percent plaque diffuseness; % APV, percent aggregate plaque volume; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; PR, positive remodeling; LAP, low attenuation plaque; SC, spotty calcifications.

3.3. Vessel characteristics and relationship with FFR

In unadjusted linear regression, there was a strong significant association for each of the vessel parameters with FFR (p <0.001 for all, Table 3). In particular, log percent PD was inversely related with FFR. That is, with an increase in the percentage of logarithmically transformed PD, there was a decline in FFR values in favor of vessel ischemia (e.g., β = −0.058 [SE = 0.010], p <0.001).

Table 3.

Linear and logistic regression for the relationship between vessel characteristics and fractional flow reserve.

| Per-vessel analysis (n=407) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable linear regression | Univariable logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regressiona | |||||||

| B | SE | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Diffuseness measures: | |||||||||

| Log % PD | −0.058 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 1.98–4.89 | <0.001 | 1.58 | 1.005–2.48 | 0.048 |

| Other CCTA measures: | |||||||||

| Diameter stenosis, % | −0.004 | 0.0004 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.05–1.09 | <0.001 | |||

| Area stenosis, % | −0.003 | 0.0003 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.04–1.08 | <0.001 | |||

| Minimal lumen diameter, mmb | 0.126 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.04–0.18 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.06–0.25 | <0.001 |

| Minimal lumen area, mm2 | 0.038 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.40 | 0.30–0.54 | <0.001 | |||

| % APV | −0.005 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.06–1.11 | <0.001 | |||

| PRb | −0.112 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 10.31 | 6.35–16.72 | <0.001 | 7.21 | 4.02–12.91 | <0.001 |

| LAPb | −0.115 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 12.90 | 5.39–30.84 | <0.001 | 2.64 | 1.38–5.04 | 0.003 |

| SC | −0.062 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 3.89 | 2.04–7.41 | <0.001 | |||

Adjusted odds ratios retained from backward stepwise logistic regression are reported.

Minimal lumen diameter, positive remodeling, and low attenuation plaque were retained in backward stepwise logistic regression.

Log % PD, logarithmically transformed percent plaque diffuseness; % APV, percent aggregate plaque volume; PR, positive remodeling; LAP, low attenuation plaque; SC, spotty calcifications; B, unstandardized coefficient; SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio.

Univariable logistic regression analyses revealed that increased log percent PD, diameter stenosis, area stenosis, percent APV, and APCs were all independent predictors of vessel-specific ischemia (all p<0.001, Table 3). Conversely, increased MLD and MLA were both independent predictors of a normal FFR. In an adjusted backward stepwise logistic regression model, retained variables in addition to log percent PD included MLD, PR, and LAP. Notably, for every unit percent increase in logarithmically transformed PD, there was a 58% (95% CI: 1.01–2.48, p =0.048) rise in the odds of having an abnormal FFR independent of stenosis severity and APCs. The global Chi-square test showed a modest, albeit significant improvement in model fit when log percent PD was added to MLD, PR, and LAP for predicting vessel-specific ischemia (e.g., 181.21 versus 185.23, p <0.045, Supplementary Fig. 2).

As a sensitivity analysis, restricting the analysis to those vessels without prior PCI (n=402), univariable logistic regression revealed that log percent PD and the measures of luminal narrowing and atherosclerotic plaque were all independent predictors of ischemia (all p <0.001). In an adjusted model, for every unit percent increase in log percent PD, there was a 60% (OR = 1.60 95% CI: 1.00–2.58, p =0.051) rise in the odds of having an abnormal FFR. In addition, as a sensitivity analysis where percent APV was forced into the adjusted model, there was a 56% (OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 0.96–2.52, p =0.072) and 2% (OR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.99–1.05, p =0.278) rise in the odds of having an abnormal FFR for every unit increase in logarithmically transformed percent PD and percent APV, respectively.

3.4. Discrimination and reclassification of vessel characteristics by CCTA

There was no further improvement in discriminatory ability by AUC when log percent PD was added to the final parsimonious model of MLD, PR, and LAP (AUC difference: 0.003, 95% CI: −0.003–0.010, p =0.33, Fig. 2). However, using the category-free NRI, percent PD added further reclassification value beyond the other CCTA parameters retained from the final adjusted model. That is, log percent PD improved category-free reclassification by 0.21 (95% CI: 0.01–0.41, p =0.04) when added to the base model of MLD, PR, and LAP.

Fig. 2. Discrimination by C-statistic for the presence of vessel-specific ischemia according to CCTA measures of coronary plaque.

Base model included minimal lumen diameter (MLD), positive remodeling (PR), and low attenuation plaque (LAP). Comparative model included the base model as well as logarithmically transformed %PD. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) indicated no improvement in discriminatory ability when log percent PD was added to final parsimonious model of MLD, PR, and LAP (p =0.33). PD, plaque diffuseness.

Based on Youden’s Index, the optimal cut-off value for percent PD was 19.4%. On the background of this cut-off value, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV were 59% (95% CI: 55–64%), 81% (95% CI: 74–87%), 47% (95% CI: 41–53%), 81% (95% CI: 73–87%), and 47% (95% CI: 41–54%), respectively.

3.5. Inter-observer and intra-observer variability

The inter-observer variability of expert quantitative CT plaque analysis (QCT) was excellent for all segments for plaque measurements, as described elsewhere (17). The inter-observer variability was reported as follows: plaque burden: intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) 0.93, p <0.001; plaque volume: ICC 0.96, p <0.001. For intra-observer variability of expert QCT, 20% of segments were randomly selected that were measured >30 days apart. The intra-observer variability revealed excellent correlation, and was reported as follows: plaque burden: ICC 0.98, p <0.001; plaque volume: ICC 0.97, p < 0.001 (17).

4. Discussion

In this prospective international multicenter study, we demonstrated the incremental impact of plaque diffuseness on vessel-specific ischemia independent of CAD severity and other high-risk plaque characteristics, as evaluated by CCTA. Although the AUC indicated that there was no improvement in discriminatory ability when log percent PD was added to other CCTA parameters, category-free NRI showed improved reclassification beyond other CCTA parameters including MLD, PR, and LAP. Notably, the current study results demonstrated that the number of diseased segments and number of lesions were poor predictors of ischemia in comparison with percent PD, and therefore, might not reflect useful proxies for diffuse coronary disease. The current study also indicated that there was moderate to good sensitivity and a rather low positive predictive value, using the optimal cut-off value of 19.4% for percent PD. These findings advocate that percent PD can potentially be used to “rule-out” rather than “rule-in” ischemic vessels. Further still, pertinent to current study findings, although the high-risk APCs on CCTA have mainly been reported in relation to the occurrence of acute events, event rates in patients with APCs were relatively low. Germane to this, Motoyama et al. demonstrated that acute event rate was 22% in the presence of 2 APCs, and only 3.7% in the presence of 1 APC during 2 years follow up (18). It is therefore plausible that in the majority of patients with APCs, acute event rates may be low and the patients may be considered stable. Still, the prevalence of APCs in the present study was high, implying a relatively high-risk population. This was also supported by the prevalence of abnormal FFR in greater than 37% of the population.

In prior event-driven studies, diffuse atherosclerosis was shown to be a measure of atherosclerosis burden, rather than plaque extent (19–22). Unique to our study is that we examined plaque diffuseness by CCTA and isolated the plaque extent separately from the plaque burden. Notably, prior studies reported that diffuse, mild, clinically silent coronary atherosclerosis detected by ICA is associated with abnormal epicardial coronary arterial resistance along with reduced myocardial blood flow prior to angiographically apparent stenosis (2,23,24). Moreover, Gould et al. demonstrated a graded, longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion gradient by stress imaging as a noninvasive marker of diffuse CAD (3). This proximal-to-distal flow gradient is attributed to fluid dynamic consequences of CAD-induced diffuse luminal narrowing as well as abnormal resistance of atherosclerotic epicardial coronary arteries without flow-limiting stenosis (2,3,25). Further still, Johnson et al. demonstrated the additive effect of diffuse disease to focal stenosis in lowering measured FFR in a theoretical model of the coronary circulation (26). Yet, data evaluating the usefulness of diffuse CAD by CCTA is considered to be suboptimal at present. Hence, in the current study, we emphasize the importance of evaluating coronary anatomy and coexistent diffuse coronary disease utilizing CCTA as a non-invasive imaging modality against the gold standard of invasive FFR. As the current study primarily focused on the pathophysiology of diffuse CAD and not the clinical utility of measuring plaque diffuseness, no comparisons were made to CCTA-derived FFR (FFRCT).

The findings of the current study are fitting with prior investigations wherein APCs were found to be strong prognosticators of ischemia (5,27,28). Previously, Park et al. demonstrated that high-risk plaque characteristics such as PR, LAP, and plaque burden determined by CCTA improved identification of ischemia (5). Our study extends upon these findings by Park et al., by additionally evaluating whether percent PD provides further incremental discriminatory and reclassification value over and above other existing CCTA parameters (5). Conversely, our results also demonstrate that the predictive value of APCs cannot be explained entirely by plaque diffuseness (29). Notably, the current study findings regarding the significance of percent APV differ from the study by Nakazato et al., which focused on lesions of intermediate stenosis severity, and the study by Park et al., which found percent APV to be predictive only in ≥50% stenotic coronary lesions (5,12). Conversely, our study evaluated the entire range of CAD severity. Further still, after exclusion of vessels with prior PCI, though statistical power was reduced, there remained a trend toward increased odds of having an abnormal FFR.

Pertinent to the current findings, while some studies have documented that conventional methods (i.e., statistical significance and C-statistics) may prove useful when attempting to test the incremental utility of a novel parameter, most often, these approaches can seem inadequate (16,30). To this end, more recently available statistical metrics including the category-free NRI tend to offer more robust incremental information as compared with the AUC (16,30). Studies have shown that important information may be overlooked when solely relying on the AUC. Further still, increases in the AUC that are often considered minimal may lead to a meaningful improvement in reclassification as quantified by the NRI (16,30). Thus, the NRI should perhaps be considered a step beyond the C-statistic, and a more robust method for testing the incremental utility of a new measure over and above already established parameters. Likewise, our global Chi-square test also displayed improved incremental risk prediction when log percent PD was added to the existing CCTA parameters for predicting vessel-specific ischemia, thereby further underlining the usefulness of other statistical approaches beyond AUC alone.

Our study has several limitations that bear mentioning. Referral and selection bias may have occurred considering patients in the DeFACTO study were enrolled if they were indicated for ICA, and invasive FFR was limited to vessels deemed clinically indicated for evaluation. Moreover, as both 100-kVp and 120-kVp were used as tube voltages in the current study, LAP might have been affected by variable kVp. Additionally, the high-risk plaque characteristic of “napkin-ring sign” was not evaluated, although it overlaps with our evaluated APCs including PR and LAP. In light of the relatively small sample size, the 95% CIs for percent PD appeared to be wide; hence, a larger sample size would be necessary in future to improve statistical power and reliability of the current study findings. Nevertheless, the present study sample of 252 patients with 407 vessels is, to our knowledge, the largest study to date that has evaluated diffuse CAD by ICA, as compared with other previous investigations (2,4). Given the limited spatial resolution of CCTA, the accuracy of CCTA parameters might have influenced the overall study findings. As such, evaluation of PD with a higher resolution technology such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT) may prove useful for confirming the present results, although any correlation with FFR as a research procedure may only be feasible in smaller cohorts.

Overall, the present study revealed that in addition to MLD and numerous APCs, percent PD determined by CCTA was independently related with coronary physiology as expressed by FFR. Although, percent PD may serve as a useful measure for determining coronary atherosclerotic plaque extent, it is currently laborious to obtain. Accurate automated percent PD measurement methods are thus warranted and may aid in its clinical implementation in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the study design. Abbreviations: FFR = fractional flow reserve; percent PD = percent plaque diffuseness

Supplementary Fig. 2. Global Chi-Square for incremental risk prediction when log percent PD (log %PD) was added to minimal lumen diameter (MLD), positive remodeling (PR), and low attenuation plaque (LAP) for predicting vessel-specific ischemia (e.g., 181.21 versus 185.23, p <0.045).

Research highlights.

Coronary CT angiography (CTA) can identify diffuse CAD.

Usefulness of diffuse CAD beyond conventional CTA parameters was examined.

Percent plaque diffuseness (PD) as a measure of diffuse CAD was obtained.

Percent PD may likely serve as an important predictor of vessel-specific ischemia.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This study was supported by a generous gift from the Dalio Institute of Cardiovascular Imaging (New York, NY, USA) and the Michael Wolk Foundation (New York, NY, USA).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Dr. Min serves as a consultant to HeartFlow. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:948–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Bruyne B, Hersbach F, Pijls NH, et al. Abnormal epicardial coronary resistance in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis but “Normal” coronary angiography. Circulation. 2001;104:2401–6. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.099316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould KL, Nakagawa Y, Nakagawa K, et al. Frequency and clinical implications of fluid dynamically significant diffuse coronary artery disease manifest as graded, longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion abnormalities by noninvasive positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2000;101:1931–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigi R, Cortigiani L, Colombo P, Desideri A, Bax JJ, Parodi O. Prognostic and clinical correlates of angiographically diffuse non-obstructive coronary lesions. Heart. 2003;89:1009–13. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.9.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park HB, Heo R, o Hartaigh B, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque characteristics by CT angiography identify coronary lesions that cause ischemia: a direct comparison to fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. JAMA. 2012;308:1237–45. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scanlon PJ, Faxon DP, Audet AM, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on Coronary Angiography). Developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1756–824. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbara S, Arbab-Zadeh A, Callister TQ, et al. SCCT guidelines for performance of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3:190–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliburton SS, Abbara S, Chen MY, et al. SCCT guidelines on radiation dose and dose-optimization strategies in cardiovascular CT. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:198–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hermann F, et al. Estimated radiation dose associated with cardiac CT angiography. JAMA. 2009;301:500–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakazato R, Shalev A, Doh JH, et al. Aggregate plaque volume by coronary computed tomography angiography is superior and incremental to luminal narrowing for diagnosis of ischemic lesions of intermediate stenosis severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:460–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki K, Matsumoto T. Dynamic change of high-risk plaque detected by coronary computed tomographic angiography in patients with subclinical coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:1667–1673. doi: 10.1007/s10554-016-0957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleg JL, Stone GW, Fayad ZA, et al. Detection of high-risk atherosclerotic plaque: report of the NHLBI Working Group on current status and future directions. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:941–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park HB, Lee BK, Shin S, et al. Clinical Feasibility of 3D Automated Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque Quantification Algorithm on Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography: Comparison with Intravascular Ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:3073–83. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3698-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H, et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancini GB, Hartigan PM, Shaw LJ, et al. Predicting outcome in the COURAGE trial (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation): coronary anatomy versus ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bittencourt MS, Hulten E, Ghoshhajra B, et al. Prognostic value of nonobstructive and obstructive coronary artery disease detected by coronary computed tomography angiography to identify cardiovascular events. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:282–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Tota-Maharaj R, et al. Improving the CAC Score by Addition of Regional Measures of Calcium Distribution: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uren NG, Melin JA, De Bruyne B, Wijns W, Baudhuin T, Camici PG. Relation between myocardial blood flow and the severity of coronary-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1782–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould KL, Kelley KO, Bolson EL. Experimental validation of quantitative coronary arteriography for determining pressure-flow characteristics of coronary stenosis. Circulation. 1982;66:930–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.5.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Keng FY, Kudo T, Sayre JS, Schelbert HR. Abnormal longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion gradient by quantitative blood flow measurements in patients with coronary risk factors. Circulation. 2001;104:527–32. doi: 10.1161/hc3001.093503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson NP, Kirkeeide RL, Gould KL. Is discordance of coronary flow reserve and fractional flow reserve due to methodology or clinically relevant coronary pathophysiology? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1371–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasterkamp G, Schoneveld AH, van der Wal AC, et al. Relation of arterial geometry to luminal narrowing and histologic markers for plaque vulnerability: the remodeling paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:655–62. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramanna N. Presence of Ischemia by FFR Without Significant Anatomic Stenosis Is Likely due to Concomitant Diffuse Disease and Not due to Impaired Vasodilation From Pharmacological Stress. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1232–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–72. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the study design. Abbreviations: FFR = fractional flow reserve; percent PD = percent plaque diffuseness

Supplementary Fig. 2. Global Chi-Square for incremental risk prediction when log percent PD (log %PD) was added to minimal lumen diameter (MLD), positive remodeling (PR), and low attenuation plaque (LAP) for predicting vessel-specific ischemia (e.g., 181.21 versus 185.23, p <0.045).