Abstract

Background

Despite insights for humans, short-term associations of air pollution with mortality to our knowledge have never been studied in animals. We investigated the association between ambient air pollution and risk of mortality in dairy cows and effect modification by season.

Methods

We collected ozone (O3), particulate matter (PM10), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations at the municipality level for 87,108 dairy cow deaths in Belgium from 2006 to 2009. We combined a case-crossover design with time-varying distributed lag models.

Results

We found acute and delayed associations between air pollution and dairy cattle mortality during the warm season. The increase in mortality for a 10 µg/m3 increase in 2-day (lag 0−1) O3 was 1.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.3%, 2.1%), and the corresponding estimates for a 10 µg/m3 increase in same-day (lag 0) PM10 and NO2 were 1.6% (95% CI = 0.0%, 3.1%) and 9.2% (95% CI = 6.3%, 12%), respectively. Compared to the acute increases, the cumulative 26-day (lag 0−25) estimates were considerably larger for O3 (3.0%; 95% CI = 0.2%, 6.0%) and PM10 (3.2%; 95% CI = -0.6%, 7.2%), but not for NO2 (1.4%; 95% CI = -4.9%, 8.2%). In the cold season, we only observed increased mortality risks associated with same-day (lag 0) exposure to NO2 (1.4%; 95% CI = -0.1%, 3.1%) and with 26-day (lag 0–25) exposure to O3 (4.6%; 95% CI = 2.2%, 7.0%).

Conclusions

Our study adds to the epidemiologic findings in humans and reinforces the evidence on the plausibility of causal effects. Furthermore, our results indicate that air pollution associations go beyond short-term mortality displacement.

Introduction

Although experimental studies on laboratory animals have been widely used to study mechanisms of air pollution-related health effects,1–3 few studies have investigated the effects of air pollution on animal health in an epidemiologic context. Pet animals have been used to study cancer, lung disease, and brain abnormalities in relation to urban air pollution4,5 or indoor exposures.4,6 Other studies have investigated effects of toxic gases, dusts and endotoxins inside farm facilities on livestock health.7 We are not aware of any study of the association between ambient air pollution and animal mortality, except for some reports of pet and farm animal deaths during historic air pollution episodes.7–10 In the 1870s, death of cattle during a livestock show in England was associated with a dense industrial fog.8 In Belgium, cattle died in the fog of 1911,9 and during the Meuse valley air pollution episode in 1930.10

Even at current pollutant levels, the relationship between air pollution and excess morbidity and mortality remains, as shown by numerous epidemiologic studies using human data.11 However, some debate still exists about the lag period associated with these exposures, which may include both harvesting and delayed effects, contributing differently to the net cumulative effects. The harvesting hypothesis states that short-term increases in air pollution simply shorten the life span of frail individuals, implying a short-term positive correlation between exposure and daily deaths, followed by a deficit in mortality at longer lags.

Studies of the association between air pollution and mortality in animal populations can corroborate or inform epidemiologic studies in humans. The advantages of using animals as comparative models of human disease accrue in part from their relative freedom from concurrent exposures, bias due to confounding, and, to some extent, exposure misclassification.4 Dairy cows have a relatively long life span, limited population variability in lifestyle and dietary habits, limited geographical mobility, and (partial) outdoor housing. Moreover, in many countries, farm animals are subject to a stringent mandatory registration procedure from birth till death, which is at the individual level for ruminants.

We investigated whether the short-term association between air pollution and mortality in humans can be corroborated in an animal population in which confounding and exposure misclassification are limited, to further elaborate on the causality of this association. We used distributed lag models12 to investigate the effect of ozone (O3), particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter less than 10 μm (PM10), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) on mortality over a 25-day period among dairy cows in Belgium. A distributed lag model has the advantage of providing cumulative effects of air pollution by flexibly estimating contributions at different lag times, thus accounting for delayed effects and short-term harvesting. In addition, we assessed potential effect modification by season by using time-varying distributed lag models.13

Methods

Data

Data on cattle mortality were extracted from Sanitrace (Sanitel), a national-level computerized database for the registration and traceability of farm animals, managed by the Belgian Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain.14 For all adult dairy cows (≥ 2 years) that died (apart from culling in slaughterhouse) in Belgium during the period 2006-2009, we obtained information on date of birth and death, farm identification, and postal code. The majority of dairy cows in Belgium are of the Holstein Friesian breed.

We obtained daily maximum 8-hour average O3 concentrations and daily average PM10 and NO2 concentrations from the Belgian Interregional Environment Agency. In Belgium, a dense network of automatic monitoring sites collects real-time data on a half hourly basis. The average distance between the nearest measuring stations is about 25 km. Data from monitoring stations were combined with land cover data obtained from satellite images in a spatial-temporal (Kriging) interpolation model, described by Janssen et al.15 This provided estimates for O3, PM10, and NO2 on a 4 x 4 km2 grid, which were then used to calculate area-weighted average concentrations per municipality (average size of 43.9 km2). Air pollution levels were linked to cattle mortality data through the postal code of the farm. For O3, the interpolation model explained more than 90% of the temporal variability (R2) and 60% of the spatial variability in Belgium.16 For PM10, the temporal variability explained was more than 70%, and the spatial variability explained was 50%. The corresponding numbers for NO2 were more than 75% and more than 80% respectively. Previous studies suggest that PM10 estimates correlate well with individual exposure, as assessed by carbon load in human macrophages.17

Because climate is a known confounder of the association between air pollution and health,18,19 data on mean air temperature and average relative humidity were provided by the Belgian Royal Meteorological Institute (KMI). We used data from one central and representative station in Uccle (Brussels), because Belgium is very uniform for temperature, as a result of extremely small altitudinal and latitudinal gradients: elevations range from 0 to 694 m above sea level, and the distance between the northernmost and southernmost part is only 224 km.

Statistical Analysis

The case-crossover design is widely used for analyzing short-term exposures with acute outcomes.20 It is a variant of the matched case-control study, where each subject serves as its own control so that known and unknown time-invariant confounders are inherently adjusted for by study design.21 This design samples only cases (deaths in this study) and compares each subject's exposure in a time period just before a case event (the hazard period) with that subject's exposure at other times (the control periods). Selection bias was avoided by applying a bidirectional time-stratified design.22 Control days are taken from the same calendar month and year as the case day (i.e. day of death), both before and after the case, thus controlling for long-term trends and season by design. Cases and controls were additionally matched by day of the week to control for any weekly patterns in deaths or pollution. A case on 1 September, for example, has four control days (8, 15, 22, and 29 September), whereas a case on 21 September has three control days (7, 14, and 28 September).

To account for potential harvesting and delayed effects of air pollution on dairy cow mortality, we combined the case-crossover design with distributed lag models, using a separate model for each of the three air pollutants. This study applies recent extensions of the distributed lag models methodology beyond aggregated time series data,23 specifically implementing them in a conditional logistic regression model with individual-level exposure measures. A distributed lag (non-linear) model is defined through a “cross-basis” function, which allows the simultaneous estimation of a (non-linear) exposure-response association and non-linear effects across lags, the latter termed lag-response association. The maximum lag was set to 25 days, meaning that the hazard period contains up to 25 days before the case day and each of the control periods contains up to 25 days before the control day. We assumed a linear air pollutant–mortality association and the lag structure was modelled with a natural cubic spline with 6 degrees of freedom. The knots in the lag space were set at equally spaced values in the log scale of lags to allow more flexible lag effects at shorter delays.24

We also included a cross-basis for mean temperature in the model to capture the (potentially delayed) effects of heat and cold on mortality. The maximum lag was set to 25 days. We used a natural cubic spline with 5 degrees of freedom for the temperature–mortality function and a natural cubic spline with 6 degrees of freedom (with knots at equally spaced values in the log scale) for the lag structure. Spline knots for temperature were placed at equally spaced values of the actual temperature range to allow enough flexibility in the two ends of the temperature distribution. Models were additionally adjusted for the moving average of humidity on the current day and the two previous days (lag 0–2), using a natural cubic spline with 3 degrees of freedom.

Potential seasonal heterogeneity in air pollution effects was investigated because: 1) human studies have reported larger effect estimates in summer than in winter,18,19 and 2) free-ranging cows are, apart from the daily milking moments, the majority of their time on pasture from March-May until October, whereas they are continuously in the stable during the other months of the year. Seasonal effect modification was addressed with time-varying distributed lag models, expressed through an interaction between the cross-basis for the air pollutant and an indicator variable for season.13 Season was defined as the warm (April-September) and the cold (October-March) period of the year. Seasonal variation was formally tested by comparing models with and without the interaction term (likelihood ratio test on 6 degrees of freedom).

In sensitivity analyses we used an unconstrained distributed lag model to define the lag structure, that is, a model in which each lag is entered as a separate variable.25,26 Because of the correlation between air pollution concentrations on days close together, the unconstrained distributed lag model will result in unstable estimates for the individual lags, but it is known as more flexible and less prone to bias for the estimate of the overall effect.25 We also investigated the potential influence of bluetongue disease on the observed results. There were two outbreaks of bluetongue virus serotype 8 in Belgium within the study period: from August to December 2006 and from July to December 2007.27 Because the spread of bluetongue in Belgium has been found to be associated with weather conditions28 and because of the correlation between meteorology and air pollution, we examined whether our results were robust to the exclusion of these epidemics from the analyses by using both constrained (as in the main analyses) and unconstrained distributed lag models. In a last sensitivity analysis, we checked the robustness of results with respect to the specification of the temperature cross-basis, varying the degrees of freedom for the exposure-response and for the lag-response functions from 3 to 7. Model fit was assessed based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

We calculated relative risks (RR) of mortality for a 10 µg/m3 increase in air pollutant concentrations. Reported estimates, computed as the overall cumulative risk accounting for the 0−25 lag period, are presented as percent change in mortality with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). All analyses were performed with the statistical software R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the “dlnm” package.24

Results

Data Description

There were 87,108 cow deaths in Belgium from 2006 to 2009. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for daily mortality, air pollutants and weather variables. In the warm season there were on average 55 cases per day and in the cold season 65 cases. The average concentrations of O3, PM10 and NO2 in the warm season were 81 μg/m3, 25 μg/m3 and 15 μg/m3 respectively, whereas the corresponding concentrations in the cold season were 48 μg/m3, 27 μg/m3 and 21 μg/m3 respectively. To highlight sufficient variation around a non-zero mean value as suggested in case-crossover studies,29 Table 1 also presents the “relevant exposure term”, which is the absolute difference between each pollutant’s levels on the case day and its average concentrations over the control days.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for Daily Cattle Mortality, Weather Conditions and Air Pollution Levels and for the Absolute Differences between the Daily Levels of Each Pollutant (Case Days) and the Average Concentrations over the Control Days, Belgium 2006-2009.

| Warm Season (N=39,979) |

Cold Season (N=47,129) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| Daily Number of Cow Deaths | |||||||||

| 55 | 22 | 12 | 145 | 65 | 26 | 0 | 162 | ||

| Exposure on Case Days | |||||||||

| O3 (µg/m3) | 81 | 26 | 16 | 222 | 48 | 20 | 2.4 | 115 | |

| PM10 (µg/m3) | 25 | 12 | 2.6 | 95 | 27 | 17 | 1.3 | 142 | |

| NO2 (µg/m3) | 15 | 7.8 | 1.0 | 60 | 21 | 11 | 1.0 | 93 | |

| Temperature (°C) | 16 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 29 | 6.2 | 4.4 | -8.2 | 19 | |

| Humidity (%) | 70 | 11 | 32 | 94 | 81 | 9.0 | 40 | 100 | |

| Exposure Difference between Case Days and Average over Control Days a | |||||||||

| O3 (µg/m3) | 18 | 16 | 0.0 | 127 | 15 | 11 | 0.0 | 60 | |

| PM10 (µg/m3) | 8.5 | 7.8 | 0.0 | 69 | 13 | 12 | 0.0 | 117 | |

| NO2 (µg/m3) | 4.7 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 32 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 56 | |

The relevant exposure term in a case-crossover design.29

SD, Standard Deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum.

Spearman correlation coefficients (r) between air pollutants and meteorological variables are presented in Table 2. Correlations were highest between PM10 and NO2 (r > 0.7 in both seasons) and between O3 and NO2 (only in the cold season, r = -0.66). The correlation between PM10 and O3 was strongest in the cold season (r = -0.53, compared with r = 0.34 in the warm season). O3 was positively correlated with temperature in both seasons (r = 0.30), whereas PM10 and NO2 were negatively correlated with temperature in the cold season (r = -0.30 and r = -0.41 respectively).

Table 2.

Matrix of Spearman Correlation Coefficients, r, between Air Pollutants and Weather Variables, Belgium 2006-2009.

| O3 | PM10 | NO2 | Temperature | Humidity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warm Season | |||||

| O3 | 1.00 | ||||

| PM10 | 0.34 | 1.00 | |||

| NO2 | 0.09 | 0.70 | 1.00 | ||

| Temperature | 0.30 | 0.13 | -0.06 | 1.00 | |

| Humidity | -0.64 | -0.32 | -0.22 | -0.29 | 1.00 |

| Cold Season | |||||

| O3 | 1.00 | ||||

| PM10 | -0.53 | 1.00 | |||

| NO2 | -0.66 | 0.75 | 1.00 | ||

| Temperature | 0.30 | -0.30 | -0.41 | 1.00 | |

| Humidity | -0.42 | -0.04 | 0.10 | -0.16 | 1.00 |

Distributed Lag Model Analyses

Results from the time-varying distributed lag models indicated seasonal heterogeneity in the association between air pollution and dairy cattle mortality, so the interaction term between season and the cross-basis for the air pollutant (p-value = 0.024 for O3, p-value = 0.342 for PM10, p-value < 0.001 for NO2) was kept in the final models.

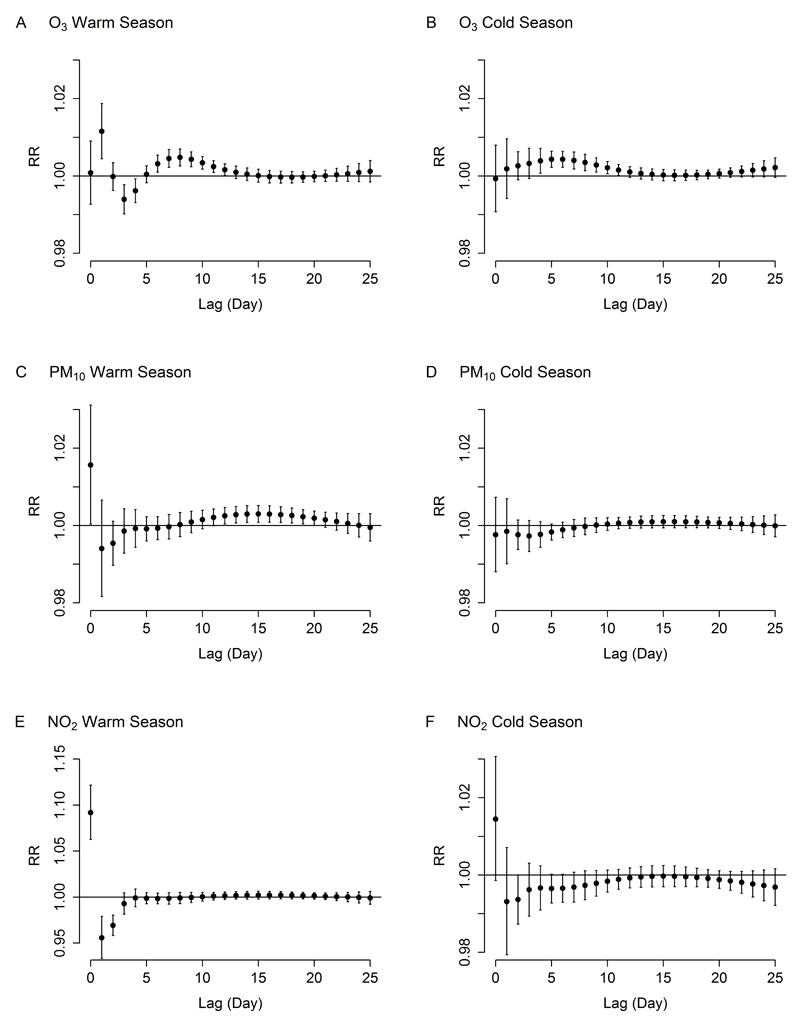

During the warm season, highest relative risks of mortality were observed on the day of exposure (PM10 and NO2) or the day after (O3), immediately followed by a 2- to 3-day deficit in mortality (Figures 1A, 1C, and 1E). For O3 and PM10, the deficit in mortality was followed by an increased mortality risk lasting for one (O3) to two (PM10) weeks. Different from results for the warm season, the lag-specific curves for O3 (Figure 1B) and PM10 (Figure 1D) in the cold season did not show acute effects (at lag 0 or lag 1), but mortality increased 4 to 11 days after O3 exposure (Figure 1B). The lag structure for NO2 in the cold season was similar to the temporal pattern in the warm season, i.e. an increase in mortality at lag 0 followed by a deficit lasting for few days, but the association in the cold season was much smaller than that in the warm season (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Lag-specific relative risks (RR, with 95% confidence interval) for dairy cow mortality associated with a 10 µg/m3 increase in air pollutant concentrations during the warm season (left panel: A, C, E for O3, PM10, NO2 respectively) and the cold season (right panel: B, D, F for O3, PM10, NO2 respectively), Belgium 2006-2009.

Cumulative effects of air pollutants on dairy cow mortality are presented in Table 3. The increase in the risk of mortality for a 10 µg/m3 increase in air pollutant concentration in the warm season was 1.2% (95% CI = 0.3%, 2.1%) for O3 (lag 0−1), 1.6% (95% CI = 0.0%, 3.1%) for PM10 (lag 0), and 9.2% (95% CI = 6.3%, 12%) for NO2 (lag 0). The overall 26-day estimates, incorporating the harvesting and delayed effects, were considerably larger than the acute effects for O3 (3.0%; 95% CI = 0.2%, 6.0%) and PM10 (3.2%; 95% CI = -0.6%, 7.2%), but not for NO2 (1.4%; 95% CI = -4.9%, 8.2%). In the cold season, we only observed increased mortality risks associated with same-day (lag 0) exposure to NO2 (1.4%; 95% CI = -0.1%, 3.1%) and with 26-day (lag 0–25) exposure to O3 (4.6%; 95% CI = 2.2%, 7.0%).

Table 3.

Cumulative Effects of Air Pollution on Dairy Cow Mortality along the Lag Days, Belgium 2006-2009. Estimates Represent the Percent Change in Dairy Cow Mortality for a 10 µg/m3 Increase in Air Pollutant Concentration.

| Lag | Percent Change (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | (Day) | O3 | PM10 | NO2 |

| Warm | 0 | 0.1 (-0.7, 0.9) | 1.6 (0.0, 3.1) | 9.2 (6.3, 12) |

| 0–1 | 1.2 (0.3, 2.1) | 1.0 (-0.5, 2.4) | 4.3 (1.5, 7.3) | |

| 0–25 | 3.0 (0.2, 6.0) | 3.2 (-0.6, 7.2) | 1.4 (-4.9, 8.2) | |

| Cold | 0 | -0.1 (-0.9, 0.8) | -0.2 (-1.2, 0.7) | 1.4 (-0.1, 3.1) |

| 0–1 | 0.1 (-0.8, 1.0) | -0.4 (-1.3, 0.5) | 0.7 (-0.8, 2.3) | |

| 0–25 | 4.6 (2.2, 7.0) | -0.5 (-3.1, 2.2) | -4.0 (-8.4, 0.6) | |

Sensitivity analyses gave similar results. The use of unconstrained distributed lag models and especially the exclusion of the bluetongue epidemics resulted in higher estimates, except for O3 in the cold season (eTable 1). Overall (26-day) warm season estimates from the unconstrained models without bluetongue epidemics were 3.3% (95% CI = 0.1%, 6.6%) for O3, 4.2% (95% CI = -0.2%, 8.8%) for PM10, and 3.9% (95% CI = -3.3%, 12%) for NO2 respectively. Corresponding estimates for the cold season were 3.6% (95% CI =0.9%, 6.3%), 3.2% (95% CI = 0.0%, 6.5%), and 0.0% (95% CI = -5.0%, 5.3%) respectively. Effect estimates were quite robust to changes in the degrees of freedom for the exposure-response and lag-response functions of the temperature cross-basis (eTable 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first epidemiologic study that uses an animal population to investigate short-term variations in mortality in association with recent exposure to air pollution. We found increases in the risk of dairy cattle mortality associated with air pollution, both particulate (PM10) and gaseous (O3 and NO2), during the warm period of the year. Exposure to NO2 was associated with a same-day increase in mortality, but this was largely compensated by a subsequent 2-day deficit in mortality. For O3 and PM10, however, the overall (lag 0−25) effects were substantially larger than the acute effects (up to lag 0−1), indicating that the adverse response to air pollution can persist weeks after the exposure. In the cold season, we only observed acute effects for NO2 and delayed effects for O3. Overall, our study in cattle corroborates findings in humans and provides further evidence that air pollution-related mortality goes beyond short-term harvesting. In broader perspective, a quantification of dairy cattle mortality related to environmental exposure is important for animal welfare and health,30 as well as for economic reasons.31

Despite the recognition that animals could be useful role models for human health risks,32 the full potential of linking animal and human health data in environmental research has not been realized.33 Possible reasons for this include the professional segregation of human and animal health communities, the separation of human and animal surveillance data, and evidence gaps in the linkages between human and animal responses to environmental health hazards.33 Our study shows that epidemiologic observations in animal populations can add to findings from human studies. Evidence for causality is strengthened because dairy cattle are expected to be relatively free from confounding factors such as the use of air conditioning, housing construction, occupational exposures, and lifestyle factors.4 The restricted daily mobility and low frequency of migration in cattle populations contribute to the likelihood that exposure assessment can be conducted relatively accurately. Moreover, the majority of adult dairy cows are on pasture during summer, making outdoor exposure a good proxy for actual individual exposure, at least in summer. In this study the case-crossover design represents an attractive alternative to Poisson models to investigate acute health effects, because of the possibility to use individual-level information on exposures. The use of distributed lag models enabled the investigation of the net effect of air pollution on cattle mortality, accounting for harvesting as well as delayed effects.

Whereas it has been argued that risk assessments using relatively short timescales might have overestimated the public health impact of air pollution because of the effect of harvesting, our analysis indicates that such studies might have underestimated the total effects. This was also suggested by some human studies that have examined the temporal pattern of the association using longer follow-up periods.26,34–37 As in our study, they found extended effects of O337 and particulates,26,34–36 with larger estimates for the overall cumulative effect than for the acute effects. As pointed out by Zanobetti et al,26 numerous epidemiologic studies have shown that air pollution is associated with exacerbation of illness, which might result in an increased recruitment into the pool of individuals at risk of dying. This may occur at different lags, depending on the mechanism and individual, and at a slower pace than death out of the risk pool, which might result in delayed increases in mortality persisting for several days or weeks. Extended air pollution effects on mortality are supported by evidence from the historical London smog episode in 1952, which was followed by elevated human mortality rates up to 3 months after the exposure.38

Results of our study provide evidence for seasonal variation in the association between ambient air pollution and dairy cattle mortality, indicating that the triggering effect of air pollution is not equally harmful under different weather conditions, even after strong adjustment for immediate and delayed effects of outdoor temperature. This finding is consistent with results from a study on human mortality in the northern part of Belgium (Flanders), reporting much larger effects of particulates during the warmer period of the year.19 Stronger associations between air pollution and daily mortality in the warm season have also been found in other human studies.18,39 We can only speculate about the mechanisms underlying the effect modification by season. It is unlikely that the difference is due to differences in outdoor concentration levels, because concentrations of both PM10 and NO2 were higher and more variable in the cold season (Table 1). However, seasonal differences in air pollution mixture or composition of PM may exist, as suggested by studies reporting a higher inflammatory activity of PM during warm periods.40,41 Human studies have shown that outdoor exposure contributes more to personal human exposure during warm periods than during cold periods,42 which is likely to be related to differences in ventilation and time spent outdoors between the two periods.

It is expected that PM2.5 (particles with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤ 2.5 µm) imposes stronger health risks than the coarse part of PM10. We were not able to use PM2.5 data in the current study, because the number of measuring stations for PM2.5 in Belgium before 2008 was less than 15, with no data in the Southern part of the country.43 For PM10 on the other hand, the number of measuring stations was above 45 in 2006 and above 60 in 2009.43 The (Spearman) correlation coefficient between daily PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in 2009 was 0.9. Another limitation of our study is that we used interpolated air pollution estimates at the level of the municipality as a proxy for individual exposure since farm addresses were not available. Although larger farms might extend across municipalities, this phenomenon should be rather exceptional because farms in Belgium are much smaller than in the US for example. Milk-specialized farms in Belgium have on average 56 cows and 47 hectares of forage area.44

Cattle are known to be susceptible to respiratory disease because of their small physiological gaseous exchange capacity, greater basal ventilatory activity, and greater anatomical compartmentalization of the lung as compared with other mammals.45 This makes bovine lungs highly susceptible to bacterial infection and lung damage. Despite physiologic and anatomic differences between cattle and human, biochemical and physiologic changes in response to air pollution exposure are expected to be similar for both species. Compared with large-scale meta-analyses and multi-city studies on human populations, which typically have examined the risk of mortality up to only a few days after exposure, our estimates for the immediate effects of air pollutants during the warm season are considerably larger. Assuming that 10-ppb O3 equals 20 µg/m3 and converting the 8-hour maximum concentration to the daily average,46 our (lag 0–1) estimate corresponds to a 4.7% increase in mortality for a 10-ppb increase in daily average O3. Estimates for humans range from 0.2% to 1.4% per 10-ppb in daily average O3.46–55 Meta-analytic and multi-city estimates for a 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10 range from 0.2% to 0.6%,48–50,54,56,57 whereas corresponding estimates for NO2 range from 0.1% to 1.2%.48,49,54,58

Only a limited number of studies on the association between air pollution and human mortality have considered lag periods longer than a few days.26,34–37 A study combining data from 21 European cities found a 21-day increase in respiratory deaths of 3.3% (95% CI = 1.9%, 4.8%) for each 10 µg/m3 increase in O3, whereas effects on total and cardiovascular mortality were only found in summer and were counterbalanced by negative effects thereafter.37 Based on data from 10 European cities, Zanobetti et al35 investigated the effect of PM10 on deaths up to 40 days after the exposure and found a 4.2% (95% CI = 1.1%, 7.4%) increase in respiratory deaths and a 2.0% (95% CI = 1.4%, 2.5%) in cardiovascular deaths for each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10. Similarly, the 41-day increase in mortality associated with a 10 µg/m3 increase in black smoke in Dublin was 3.6% (95% CI = 3.0%, 4.3%) for respiratory mortality, but only 1.1% (95% CI = 0.8%, 1.3%) for total mortality.36 The 41-day increased risk of total mortality associated with a 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10 estimated for 10 European cities was 1.6% (95% CI = 1.0%, 2.2%).34

Our study replicates epidemiologic findings for humans, but in a more controlled and stable context, as socio-demographic confounding and exposure misclassification are limited in dairy cattle. This reinforces the evidence on the plausibility of causal effects in humans, and suggests that there are common pathophysiological patterns. In addition, our findings provide further evidence that acute exposures have long-lasting effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

This study was supported by the European Research Council (ERC-310898), the Flemish Research Council (FWOG073315N), and Hasselt University Fund (BOF). Dr Gasparrini was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (grants ID: MR/M022625/1 and G1002296).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kodavanti UP, Costa DL. 10 - Animal Models to Study for Pollutant Effects. In: Holgate ST, Samet JM, Koren HS, Maynard RL, editors. Air Pollution and Health. New York: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 165–197. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godleski JJ, Verrier RL, Koutrakis P, et al. Mechanisms of morbidity and mortality from exposure to ambient air particles. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2000:5–88. discussion 89-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watkinson WP, Campen MJ, Nolan JP, Costa DL. Cardiovascular and systemic responses to inhaled pollutants in rodents: effects of ozone and particulate matter. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl 4):539–46. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reif JS. Animal sentinels for environmental and public health. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(suppl 1):50–7. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderon-Garciduenas L, Mora-Tiscareno A, Ontiveros E, et al. Air pollution, cognitive deficits and brain abnormalities: a pilot study with children and dogs. Brain Cogn. 2008;68:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukowski JA, Wartenberg D. An alternative approach for investigating the carcinogenicity of indoor air pollution: pets as sentinels of environmental cancer risk. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:1312–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.971051312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van den Hoven R. Air Pollution and Domestic Animals. In: Moldovean A, editor. Air Pollution New Developments. Rijeka: Intech; 2011. pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veterinarian. The effects of the recent fog on the Smithfield Show and the London dairies. Veterinarian. 1874;47:32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertyn F. Le brouillard et le bétail. Ann Gembloux. 1913;25:153–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemery B, Hoet PH, Nemmar A. The Meuse Valley fog of 1930: an air pollution disaster. Lancet. 2001;357:704–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunekreef B, Holgate ST. Air pollution and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1233–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, Kenward MG. Distributed lag non-linear models. Stat Med. 2010;29:2224–34. doi: 10.1002/sim.3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, et al. Temporal variation in heat-mortality associations: a multicountry study. Environ Health Perspect. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409070. [published online ahead of print May 1, 2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain. Sanitel [in Dutch] [Accessed February 26, 2015]; http://www.favv-afsca.be/dierlijkeproductie/dieren/sanitel/

- 15.Janssen S, Dumont G, Fierens F, Mensink C. Spatial interpolation of air pollution measurements using CORINE land cover data. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:4884–4903. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiheu B, Veldeman N, Viaene P, et al. Identifying the best available large-scale concentration maps for air quality in Belgium, study commissioned by the Flemish Environment Agency (VMM), MIRA, MIRA/2013/01. Flemish Institute for Technological Research (VITO); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs L, Emmerechts J, Mathieu C, et al. Air pollution related prothrombotic changes in persons with diabetes. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:191–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Spix C, et al. Short-term effects of ambient sulphur dioxide and particulate matter on mortality in 12 European cities: results from time series data from the APHEA project. Air Pollution and Health: a European Approach. BMJ. 1997;314:1658–63. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7095.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawrot TS, Torfs R, Fierens F, et al. Stronger associations between daily mortality and fine particulate air pollution in summer than in winter: evidence from a heavily polluted region in western Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:146–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nawrot TS, Perez L, Kunzli N, Munters E, Nemery B. Public health importance of triggers of myocardial infarction: a comparative risk assessment. Lancet. 2011;377:732–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:144–53. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy D, Lumley T, Sheppard L, Kaufman J, Checkoway H. Referent selection in case-crossover analyses of acute health effects of air pollution. Epidemiology. 2001;12:186–92. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasparrini A. Modeling exposure-lag-response associations with distributed lag non-linear models. Stat Med. 2014;33:881–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasparrini A. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models in R: the package dlnm. J Stat Softw. 2011;43:1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz J. The distributed lag between air pollution and daily deaths. Epidemiology. 2000;11:320–6. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zanobetti A, Wand MP, Schwartz J, Ryan LM. Generalized additive distributed lag models: quantifying mortality displacement. Biostatistics. 2000;1:279–92. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meroc E, Herr C, Verheyden B, et al. Bluetongue in Belgium: episode II. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2009;56:39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2008.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ensoy C, Aerts M, Welby S, Van der Stede Y, Faes C. A dynamic spatio-temporal model to investigate the effect of cattle movements on the spread of bluetongue BTV-8 in Belgium. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunzli N, Schindler C. A call for reporting the relevant exposure term in air pollution case-crossover studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:527–30. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.027391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silanikove N. Effects of heat stress on the welfare of extensively managed domestic ruminants. Livest Prod Sci. 2000;67:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.St-Pierre NR, Cobanov B, Schnitkey G. Economic losses from heat stress by US livestock industries. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:E52–E77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Schalie WH, Gardner HS, Jr, Bantle JA, et al. Animals as sentinels of human health hazards of environmental chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:309–15. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabinowitz P, Conti L. Links among human health, animal health, and ecosystem health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:189–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, Samoli E, et al. The temporal pattern of mortality responses to air pollution: a multicity assessment of mortality displacement. Epidemiology. 2002;13:87–93. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, Samoli E, et al. The temporal pattern of respiratory and heart disease mortality in response to air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1188–93. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodman PG, Dockery DW, Clancy L. Cause-specific mortality and the extended effects of particulate pollution and temperature exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:179–85. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samoli E, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, et al. The temporal pattern of mortality responses to ambient ozone in the APHEA project. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:960–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.084012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell ML, Davis DL. Reassessment of the lethal London fog of 1952: novel indicators of acute and chronic consequences of acute exposure to air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl 3):389–94. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng RD, Dominici F, Pastor-Barriuso R, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Seasonal analyses of air pollution and mortality in 100 US cities. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:585–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hetland RB, Cassee FR, Lag M, Refsnes M, Dybing E, Schwarze PE. Cytokine release from alveolar macrophages exposed to ambient particulate matter: heterogeneity in relation to size, city and season. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2005;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Happo MS, Hirvonen MR, Halinen AI, et al. Seasonal variation in chemical composition of size-segregated urban air particles and the inflammatory activity in the mouse lung. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:17–32. doi: 10.3109/08958370902862426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorensen M, Loft S, Andersen HV, et al. Personal exposure to PM2.5, black smoke and NO2 in Copenhagen: relationship to bedroom and outdoor concentrations covering seasonal variation. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15:413–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fierens F, Vanpoucke C, Adriaenssens S, et al. Air Quality in Belgium 2011. Annual Report. Belgian Interregional Environment Agency (IRCEL-CELINE); 2011. [Accessed November 18, 2015]. http://www.irceline.be/en/documentation/publications/annual-reports/annual-report-2011/view. [Google Scholar]

- 44.European Commission. EU dairy farms report 2013 based on FADN data. European Commission - EU FADN; 2014. [Accessed November 18, 2015]. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/pdf/Dairy_Farms_report_2013_WEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veit HP, Farrell RL. The anatomy and physiology of the bovine respiratory system relating to pulmonary disease. Cornell Vet. 1978;68:555–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell ML, Dominici F, Samet JM. A meta-analysis of time-series studies of ozone and mortality with comparison to the national morbidity, mortality, and air pollution study. Epidemiology. 2005;16:436–45. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000165817.40152.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thurston GD, Ito K. Epidemiological studies of acute ozone exposures and mortality. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11:286–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stieb DM, Judek S, Burnett RT. Meta-analysis of time-series studies of air pollution and mortality: update in relation to the use of generalized additive models. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2003;53:258–61. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2003.10466149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dominici F, McDermott A, Daniels M, Zeger S, Samet J. Revised analyses of time-series studies of air pollution and health. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute; 2003. Mortality among residents of 90 cities; pp. 9–24. Special report. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Peacock JL, Marston L, Konstantinou K. Meta-analysis of time-series studies and panel studies of Particulate Matter (PM) and Ozone (O3) Report of a WHO task group. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bell ML, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM, Dominici F. Ozone and short-term mortality in 95 US urban communities, 1987-2000. JAMA. 2004;292:2372–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ito K, De Leon SF, Lippmann M. Associations between ozone and daily mortality: analysis and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2005;16:446–57. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000165821.90114.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy JI, Chemerynski SM, Sarnat JA. Ozone exposure and mortality: an empiric bayes metaregression analysis. Epidemiology. 2005;16:458–68. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000165820.08301.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong CM, Vichit-Vadakan N, Kan H, Qian Z. Public Health and Air Pollution in Asia (PAPA): a multicity study of short-term effects of air pollution on mortality. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1195–202. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng RD, Samoli E, Pham L, et al. Acute effects of ambient ozone on mortality in Europe and North America: results from the APHENA study. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2013;6:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s11869-012-0180-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Samoli E, et al. Confounding and effect modification in the short-term effects of ambient particles on total mortality: results from 29 European cities within the APHEA2 project. Epidemiology. 2001;12:521–31. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samoli E, Peng R, Ramsay T, et al. Acute effects of ambient particulate matter on mortality in Europe and North America: results from the APHENA study. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1480–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samoli E, Aga E, Touloumi G, et al. Short-term effects of nitrogen dioxide on mortality: an analysis within the APHEA project. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:1129–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00143905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.