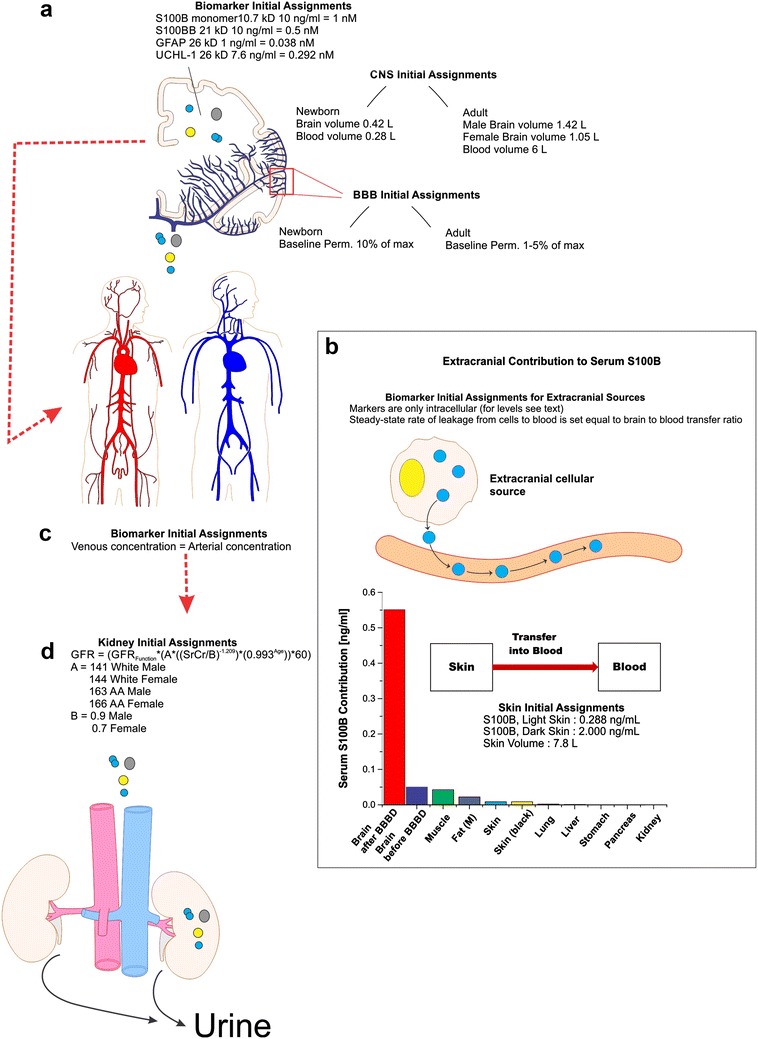

Fig. 1.

Initial assignments and assumptions for the pharmacokinetic model. The illustrations provide a region-specific grouping of all initial assignments and assumptions considered in our kinetic modeling of biomarker distribution. A detailed graphic and mathematical description of the model is in Additional file 2: Figure S2. Parameters incorporated into the CNS a included: (1) molecular weight and concentration of biomarkers; (2) neonatal brain volume and volemia; (3) adult male/female brain volume and volemia; and (4) homeostatic (pre-BBBD) permeability levels across the BBB (see “Methods” section). Extracranial contributions to serum biomarker levels b do not significantly differ from a model whose only contribution comes from the brain. Extracranial sources of S100B were quantified using data from [11], and each organ was set to a fixed (1–5%) rate of marker’s transfer to blood. The corresponding bar plot shows organ-specific contribution to serum levels. The flowchart in the inset shows a simplified diagram of the skin-to-blood contribution of S100B in the pharmacokinetic model. Arterial and venous blood volumes were combined into a common, systemic blood compartment c and an assumption of homogeneity was employed for serum biomarker levels. The blood compartment was provided an initial biomarker concentration of 0 ng/ml. Passage of biomarker mass into the kidneys d was dependent on initial assignment of glomerular filtration rate (GFR), as calculated by the Cockroft-Gault formula for both African American (A–A) and Caucasian male and female adults. Neonatal kidney filtration was preset to 47 ml/min/1.73 m2 (see Table 1)