Abstract

Nucleoside hydrolases (NHs) catalyze the hydrolysis of the N‐glycoside bond in ribonucleosides and are found in all three domains of life. Although in parasitic protozoa a role in purine salvage has been well established, their precise function in bacteria and higher eukaryotes is still largely unknown. NHs have been classified into three homology groups based on the conservation of active site residues. While many structures are available of representatives of group I and II, structural information for group III NHs is lacking. Here, we report the first crystal structure of a purine‐specific nucleoside hydrolase belonging to homology group III from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (CeNH) to 1.65Å resolution. In contrast to dimeric purine‐specific NHs from group II, CeNH is a homotetramer. A cysteine residue that characterizes group III NHs (Cys253) structurally aligns with the catalytic histidine and tryptophan residues of group I and group II enzymes, respectively. Moreover, a second cysteine (Cys42) points into the active site of CeNH. Substrate docking shows that both cysteine residues are appropriately positioned to interact with the purine ring. Site‐directed mutagenesis and kinetic analysis proposes a catalytic role for both cysteines residues, with Cys253 playing the most prominent role in leaving group activation.

Keywords: nucleoside hydrolase, leaving group activation, X‐ray crystallography, SAXS, enzyme mechanism, N‐ribohydrolase

Short abstract

PDB Code(s): 5MJ7

Introduction

Nucleosides and their derivatives are fundamentally important molecules in all living organisms, not only as the building blocks of DNA and RNA but also in cellular signaling, energy storage, and in enzymatic activity by serving as cofactors. Accordingly, all living species have developed ways to obtain these crucial components, either through de novo synthesis or by salvage pathways. Very often one of the first steps in these salvage pathways is catalyzed by nucleoside hydrolases or nucleoside phosphorylases that split the nucleosides in their constituent base and either ribose or ribose‐1‐phosphate, respectively.1, 2, 3

Nucleoside hydrolases (NH, EC3.2.2.) are Ca2+‐containing metalloenzymes that hydrolyze the N‐glycosidic bond of β‐ribonucleosides.2 They are widespread in nature, and representatives from the three domains of life, including eubacteria, archaea, yeast, protozoa, plants, insects, and mesozoans, have been characterized in different levels of detail.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 However, no representatives are present in humans. Most attention has so far been devoted to the NHs from parasitic protozoa, including different Leishmania and Trypanosoma species. NHs have been considered as attractive drug targets in these organisms, taking into account their central role in the purine salvage pathway while many of these parasitic protozoa lack a de novo purine biosynthesis pathway.17, 18, 19, 20, 21 More recently, it was also proposed that vaccine development against NHs would prevent the replication of several pathogens during their early stages of life.22, 23 Interestingly, in many other organisms NHs are present in parallel to a de novo purine biosynthetic pathway and nucleoside phosphorylases. Often in these organisms the specificity constants (k cat/K M) of the NHs for the canonical nucleosides are substantially lower compared to the NHs of protozoa.24, 25 Therefore, the precise physiological role of these enzymes in bacteria and higher eukaryotes is yet to be completely clarified. Previous work indicates various species‐specific roles, including prevention of spore formation by inosine in Bacillus cereus or Bacillus anthracis,26, 27 host anesthesia in the mosquito Aedes aegypti,11 removal of ATP from the extracellular matrix of plant cells after its signaling function,28 metabolism of the nucleotide nicotinamide riboside in yeast,25 and hydrolysis of modified nucleotides in tRNA.5, 6

Traditionally, NHs have been classified either based on their substrate specificity or based on sequence patterns of active site residues. Initially, NHs were subdivided into purine‐specific (IAG‐NH),29, 30 pyrimidine‐specific (CU‐NH),31 6‐oxopurine‐specific (IG‐NH),12 and nonspecific (IU‐NH) NHs.13 Moreover, recently several NHs have been described that show a very broad specificity, accepting not only the canonical purine and pyrimidine nucleosides as substrate, but also several other nucleoside derivatives and even the corresponding nucleotides.25, 28 An alternative classification into group I to III NHs is based on the conservation of active site residues.5 Group I enzymes contain a conserved histidine in the active site, which is replaced by a tryptophan in group II. While homology group I enzymes encompass both pyrimidine‐specific and nonspecific NHs, the group II enzymes seem to be specific for purine nucleosides. Enzymes from the relatively unexplored group III have a cysteine residue in their active site that replaces the corresponding histidine or tryptophan.

The active site histidine residue in group I NHs was initially shown to play a catalytic role in leaving group activation via protonation of the nucleoside base.14, 32 However, more recently it was shown that this histidine performs its task in leaving group activation via a different mechanism in the hydrolysis of purine and pyrimidine nucleosides.33 While protonation of the pyrimidine ring is the result of a direct interaction of the catalytic histidine with the O2 carbonyl of the base, protonation of purines occurs via two extra tyrosine residues that channel the proton from the catalytic histidine to the N7 of the purine ring.33 On the other hand, in group II NHs, the purine leaving group is protonated directly on its N7 atom by an ordered water channel connecting the N7 to bulk solvent. Aromatic stacking of the nucleic base to the active site tryptophan increases the pK a of the N7 atom sufficiently to allow direct protonation.34, 35 The remarkable variety and plasticity of the leaving group activation mechanism of NHs is further underpinned by two purine and pyrimidine specific isozymes from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus that contain a proline residue at the position corresponding to the catalytic histidine in other group I enzymes.24 For group III enzymes, the catalytic mechanism and the role of the active site cysteine residue has not yet been determined, mainly due to lack of structural information.

We earlier purified a member of the group III NHs from the multicellular nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and showed that it displays specificity toward purine nucleosides.9 In this article, we report the crystal structure of the purine‐specific nucleoside hydrolase of C. elegans (CeNH). This enzyme is characterized by two active site cysteine residues, of which one (Cys253) is analogous to the catalytic histidine or tryptophan, while the second corresponds to an asparagine or aspartate residue in group I and group II NHs, respectively. Using site‐directed mutagenesis and kinetic analysis we show that both residues are important for catalysis, with Cys253 playing an important role in leaving group activation. These results represent the first structural and detailed biochemical characterization of a group III NH.

Results and Discussion

Crystal structure and overall fold of CeNH

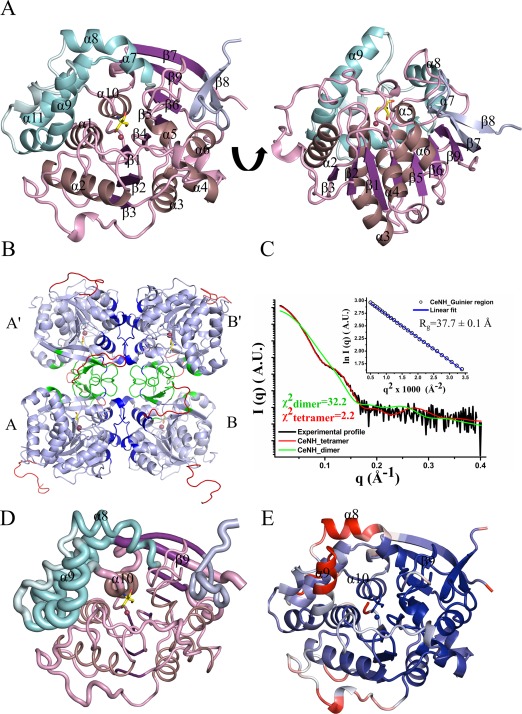

The crystal structure of the group III NH from C. elegans (CeNH) was solved at 1.65 Å resolution using molecular replacement with the structure of the 6‐oxopurine‐specific NH from Trypanosoma brucei brucei (pdb: 3FZ0) as a search model [Fig. 1(A), Table 1]. The protein is crystallized in space group P41212 with a homodimer in the asymmetric unit. However, using crystal symmetry operations a plausible tetramer assembly is obtained [Fig. 1(B)]. Such a tetrameric arrangement of the protein is also in agreement with small angle X‐ray scattering experiments [theoretical MWtetramer = 154.0 kDa; experimental MWtetramer using the Q R method = 135 kDa; Fig. 1(C), Supporting Information Table S1].

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of CeNH. (A) Top and side view of a CeNH subunit in cartoon representation. The central core of the structure is colored in different shades of purple, with α‐helices colored violet, β‐strands colored purple and coils colored pink. The α‐helices of the helical bundle are colored cyan with the intervening loops colored pale cyan. The β‐strand insertion is shown in light blue. A Tris molecule and Ca2+‐ion bound to the active site are shown as yellow sticks and as a red sphere, respectively. (B) Homotetramer assembly of CeNH obtained from crystal symmetry operation. Subunits are indicated with A and B and their symmetry variants with A' and B'. Regions forming the A‐B or A'‐B' interface are shown in dark blue; regions forming the A‐A' or B‐B' interfaces are shown in green. The missing residues in the crystal structure were modeled using MODELLER and are shown in red. (C) Superposition of the experimental SAXS trace (black) on the theoretical SAXS profiles calculated from the CeNH tetramer (red) and the dimeric CeNH arrangement found in the asymmetric unit (green) using CRYSOL. The inset figure shows the linear Guinier region for the experimental SAXS profile. (D) A “Sausage” representation of CeNH that maps the rmsd deviation per Cα atom after superposition of CeNH on all NH structures available in the PDB (using ENDscript36). The thickness of the tube is proportional to the mean rmsd per residue. The color coding is similar to (A). (E) Cartoon representation of a CeNH subunit colored based on the B factors. The regions with a blue color are the residues with low B factor while the regions with a red color represent residues with high B factors. Gray colored regions have intermediate B factors.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Data collection and processing | |

|---|---|

| X‐ray source | Beamline X13 (EMBL, DESY, Hamburg) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.8075 |

| Resolution range (Å)a | 24.93–1.65 (1.71–1.65) |

| Total/unique reflections | 2,471,907/110,218 |

| R merge (%) | 7.1 (57.9) |

| I/σ | 44.9 (2.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.2 (76.2) |

| Redundancy | 22.42 |

| Spacegroup | P 41 21 2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 84.578 84.578 260.911 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90 90 90 |

| Model refinement | |

| R work/R free (%) | 0.14 (0.23)/0.15 (0.25) |

| Rmsd bond length (Å) | 0.014 |

| Rmsd bond angle (°) | 1.33 |

| Ramachandran: favored/allowed/disallowed regions (%) | 97/2.9/0 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Clear electron density is present for the backbone of 643 out of the 700 amino acids in the two subunits in the asymmetric unit. Residues 1 to 3 and 295 to 307 for subunit A and residues 1 to 4 and 296 to 308 for subunit B are missing in the electron density due to flexibility. Additionally, the 12 residues of the N‐terminal His‐tag are also missing in both subunits. The subunit structure of CeNH closely resembles those of other NHs. The superposition of a single subunit of CeNH onto those of other available NH structures gives a root mean square deviation (rmsd) ranging from 1.53 to 2.00 Å. The highest structural similarity is found with the purine‐specific NH from S. solfataricus (PDB:3t8i, rmsd 1.54 Å), the nonspecific NH from Crithidia fasciculata (PDB: 2mas, rmsd 1.53 Å), and the 6‐oxopurine‐specific NH from T. brucei brucei (PDB: 3fz0, rmsd 1.58 Å), while the largest difference is observed with the purine‐specific NHs from T. brucei brucei (PDB:4i73, rmsd 2.0 Å) and Trypanosoma vivax (PDB: 1kic, rmsd 2.0 Å). Each subunit consists of a central eight‐stranded mixed β‐sheet and surrounding α‐helices, where the first six parallel β‐strands (β1‐β6) together with the intervening α‐helices (α1–α6, α10) adopt a Rossmann‐fold‐like structure [Fig. 1(A), purple]. Three α‐helices (α7–α9) are inserted between the last β‐strand and last α‐helix of the Rossmann‐fold that, together with the C‐terminal α‐helix (α11), form an all helical inserted domain stacked to one side of the central domain [Fig. 1(A), cyan]. Finally, a peptide region is inserted between the last two β‐strands (N‐terminal part of β7 and β9) of the central β‐sheet. This region forms an additional short antiparallel two‐stranded β‐sheet [C‐terminal part of β7 and β8; Fig. 1(A), light blue].

Mapping of rmsd values, resulting from the superposition of a subunit of all currently available NH structures, on the CeNH structure allows to distinguish structurally conserved regions from highly variable or flexible regions [Fig. 1(D)]. This analysis shows that besides β9 and α10 the core region of the protein, consisting of the central eight‐stranded β‐sheet and the intervening α‐helices, is highly structurally conserved. The all‐helical insertion as well as the β‐sheet insertion are more diverse among different NHs. The high flexibility of α8 and the C‐terminal part of α9 and α10, which together make up a part of the substrate binding pocket, is also reflected in high B‐factors in the CeNH crystal structure [Fig. 1(E)].

The overall tetramer assembly is formed via two distinct interfaces which bury a surface area of 1025 Å2 and 890 Å2, respectively [Fig. 1(B)]. The first interface is formed though interactions between residues from the loop region connecting β5 to α5 and the loops and two‐stranded β‐sheet inserted between the N‐terminal part of β7 and β9. The second interface is formed through residues of the loop regions connecting β3 to α3 and α4 and α5. This tetramer assembly is similar to the one observed in nonspecific NHs from C. fasciculata and Leishmania major, in pyrimidine‐specific NHs from Escherichia coli (RihA and RihB) and S. solfataricus, in the 6‐oxopurine‐specific NH from T. brucei brucei and the purine‐specific NH from S. solfataricus. However, this assembly and the involved residues are completely different from the dimeric arrangement of T. vivax IAG‐NH. This observation underscores that the substrate specificity of nucleoside hydrolases is not linked to their oligomeric arrangement.

Active site arrangement and substrate binding

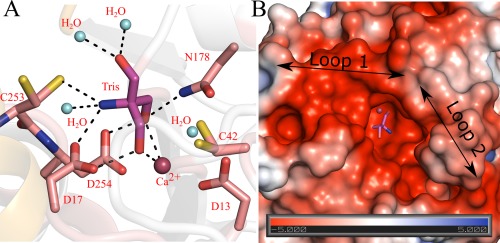

Similar to other nucleoside hydrolases, the active site of CeNH is located in a deep cavity at the C‐terminal end of the central β sheet (Fig. 2). A Ca2+ ion is tightly bound to the bottom of the cavity interacting with the side chains of Asp13, Asp18 (bidentate), Asp254 and the main chain carbonyl oxygen of Ile 133 (not shown). The octahedral coordination sphere of the Ca2+ ion is further satisfied via the interaction with a water molecule and an active site‐bound Tris molecule coming from the crystallization buffer. The Ca2+ interacting water molecule is proposed to act as the nucleophile in the hydrolysis reaction, while Asp13 is proposed to act as the catalytic base to increase the nucleophilicity of the water molecule concomitant with attack on C1′‐N9 bond of the nucleoside.2 Interestingly, two hydroxyl groups of the Tris molecule interact with the Ca2+ ion and thus mimic the typical interactions of the 2′ and 3′ hydroxyl groups of the ribose moiety of genuine nucleoside substrates, as observed in the structure of substrate‐ or inhibitor‐bound nucleoside hydrolases (Supporting Information Fig. S2). The Tris molecule in the active site is further tightly bound via interactions with Asp17, Asn178, Asp254, and Cys253 [Fig. 2(A)]. The nucleobase binding pocket of nucleoside hydrolases is typically formed by two flexible regions (traditionally termed “loop1” and “loop 2”) that close over the active site upon substrate binding.37 These two regions correspond to the β3‐α3 loop (residues 74–87) and the C‐terminal end of α9 (residues 244–250) in the CeNH crystal structure [Fig. 2(B)]. Both regions could be fully traced in our structure, and, although the B factors of loop1 residues are comparable to the rest of the protein (33 Å2), the B factors of loop 2 residues are significantly higher [up to 63.4 Å2, see Fig. 1(D,E)]. This suggests that at least loop 2 might undergo an induced fit motion upon substrate binding.

Figure 2.

Active site arrangement of CeNH. (A) Close up view of the CeNH active site showing the bound Tris molecule and Ca2+ ion. The residues and the Tris molecule are shown in stick representation with differently colored carbon atoms. The Ca2+ ion is shown as a red sphere. A Ca2+‐interacting water molecule, corresponding to the nucleophile and three Tris interacting water molecules are shown as cyan spheres. Residues interacting with the Tris molecules are shown as sticks and the hydrogen bonds as dotted lines. Residues interacting with the Ca2+ ion are not shown. (B) Electrostatic potential surface around the active site cavity of CeNH. The bound Tris molecule is shown in sticks representation. The position of the two active site regions, “loop1” and “loop2” is indicated.

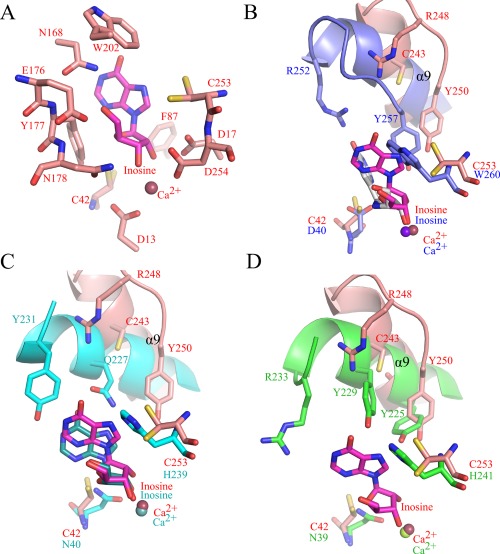

Since all attempts to co‐crystallize CeNH with substrates or inhibitors failed so far we resorted to docking of the substrate inosine in the active site of CeNH using AutoDock 4.0. Hereto, we used the coordinates of inosine from the crystal structure of the YeiK‐inosine complex (PDB code: 3B9X). In this structure inosine is bound in a conformation with a 04′‐C1′‐N9‐C4 dihedral angle of −52°.33 The calculation resulted in 20 inosine conformations docked in the CeNH active site. Sixteen of 20 docking calculations gave conformations with an average minimum free energy of binding of −6.40 ± 0.04 kcal/mol and superimpose very well on to each other (Supporting Information Fig. S3). The inosine conformation with minimum energy (AutoDock scoring) was used to generate the final model of the CeNH‐inosine complex [Fig. 3(A)]. As a control, this docking was also repeated starting from inosine in an anti‐conformation (04′‐C1′‐N9‐C4 dihedral angle of −173°), as observed in the structure of Immucillin H bound to the T. vivax IAG‐NH.37 Reassuringly, a very similar final docking result was obtained (not shown).

Figure 3.

Substrate docking model of CeNH and structural superposition with representatives of group I and group II NHs. (A) Inosine docked to the active site of CeNH (best Autodock pose is shown). Active site residues in contact with the docked ligand are shown as sticks. The inosine molecule is shown in sticks representation with its carbon atoms colored magenta. The Ca2+ ion is shown as a red sphere (B) Superposition of the active sites of CeNH and T. vivax IAG‐NH (homology group II) bound to Immucillin‐H (PDB 2FF2). Residues surrounding the base of the nucleoside (inosine or Immucillin‐H) are shown as sticks. The color coding for CeNH is identical to (A). Residues of T. vivax IAG‐NH are colored blue and Immucillin‐H gray. Helix α9 (loop2) is shown in cartoon representation. (C) Superposition of the active sites of CeNH and the CU‐NH YeiK (homology group I) bound to inosine (PDB 3B9X). The representation is identical to (B) with YeiK residues colored cyan and YeiK‐bound inosine colored dark cyan. (D) Superposition of the active sites of CeNH and the C. fasciculata IU‐NH ((homology group I) (PDB 2MAS). The representation is identical to (B) with C. fasciculata IU‐NH residues colored green.

The docking model shows that the interactions with the ribose moiety of the nucleoside are very well conserved among nearly all NHs characterized so far. The 2′‐ and 3′‐hydroxyl groups form extensive interactions with the side chains of Asp17, Asn178, and Asp254. The 5′‐hydroxyl is tightly bound via interactions with Asn168 and Glu176 [Fig. 3(A)]. In contrast, the surrounding residues and interactions with the purine ring are quite different compared to the structures available so far. However, care should be taken with interpretation of these interactions since conformational changes in the loop 1 and 2 regions are possible upon substrate binding, which might in turn also affect the conformation of the nucleic base compared to the one in our docking model. In our docking model inosine is bound in a conformation with the base in between a syn and anti‐orientation vis‐à‐vis the ribose moiety (04′‐C1′‐N9‐C4 dihedral angle of −54°). This is very close to the conformation of inosine bound to the pyrimidine‐specific YeiK from E. coli 33 but differs significantly from the analogues torsion angle of the transition state analogue Immucillin H bound to the purine‐specific NH from T. vivax 17, 37 [Fig. 3(A–D)]. The hypoxanthine base of the docked inosine substrate is surrounded by a number of hydrophobic/aromatic residues, including Phe87, Tyr177, and Trp202 [Fig. 3(A)]. Trp202 is highly conserved in group III NHs and might be important for nucleoside binding. Anticipated conformational changes in the loop 2 region upon substrate binding might bring additional residues into the binding pocket. These residues include Arg248 and Tyr250, corresponding to Arg252 and Tyr257 in the purine‐specific enzyme from T. vivax [Fig. 3(B)]. In the latter enzyme these two residues contribute to the mechanism of loop2 opening and closing upon substrate binding and product release.17

Finally, two cysteine residues, Cys42 and Cys253 are present in the nucleobase‐binding pocket of CeNH. Cys253 is the hallmark residue of group III NHs, which corresponds to a histidine in group I NHs and a tryptophan in group II NHs (Supporting Information Fig. S1, Fig. 3). Cys42 corresponds to an asparagine residue in group I NHs and an aspartate residue in group II NHs. However, also in the majority of group III enzymes this latter cysteine residue is substituted by an asparagine (Supporting Information Fig. S1). In the crystal structure Cys253 is present in two alternative conformations and one could assume that one of these conformations will be selected out upon substrate binding. In our docking model the thiol group of Cys253 is within 3.4 Å of the N7 atom of the hypoxanthine base. The tryptophan residue that substitutes for Cys253 in purine‐specific group II NHs has been shown to play a role in leaving group activation by increasing the pK a of the nucleic base, allowing a direct protonation on the N7 atom by an ordered water channel [Fig. 3(B)].34 On the other hand, in group I NHs the position of this cysteine is taken by a histidine residue. Also this histidine residue has been shown to contribute significantly to leaving group activation.32 In pyrimidine hydolysis by group I CU‐NHs or IU‐NHs this presumably occurs via a direct proton transfer from this histidine residue to the pyrimidine base [Fig. 3(C,D)]. In purine hydrolysis by group I IU‐NHs it has been proposed that the proton is relayed from this histidine to the N7 of the purine base, via two tyrosine residues in a His‐Tyr‐Tyr catalytic triad (His241–Tyr225–Tyr229 using C. fasciculata IU‐NH numbering) [Fig. 3(D)].33 In our docking model, Cys42 is located at 4.9 Å from the 2'OH and at 5.5 Å from the N3 atom of the docked inosine. In group I NHs the corresponding asparagine residue has been shown to be involved in substrate recognition via interaction with the 2′‐OH.5, 38 On the other hand in group II NHs, the corresponding aspartate residues interacts with the N3 atom of the purine ring and might to a certain extend contribute to leaving group activation.37

Mutagenesis studies reveal a role in leaving group activation for Cys253 and Cys42

Although the enzyme from C. elegans belongs to the group III NHs (Supporting Information Fig. S1) it clearly shows the kinetic fingerprint of a purine‐specific nucleoside hydrolase. Indeed, k cat/K M values for the common purine nucleosides are a factor 100 to 1000 higher compared to those for the common pyrimidine nucleosides, owing both to a higher k cat value and a lower K M value.9 To investigate the role of Cys253 and Cys42 in purine nucleoside binding and hydrolysis we generated the corresponding C253A and C42A variants though site‐directed mutagenesis and compared their kinetic properties with those of the wild type protein (note that the data reported in the current paper are measured at 25°C, while previously they were determined at 37°C) (Table 2).9

Table 2.

Kinetic Constants of Wild‐Type and Mutant CeNH

| Substrate | CeNH Wild‐type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| k cat (s−1) | K M (µM) | k cat/K M (M −1 s−1) | |

| Inosine | 0.203 ± 0.003 | 129 ± 8 | 1,574 ± 100 |

| Adenosine | 0.418 ± 0.014 | 77 ± 10 | 5,429 ± 728 |

| Guanosine | 0.143 ± 0.006 | 68 ± 11 | 2,103 ± 351 |

| p‐NPR | 0.039 ± 0.002 | 0.32 ± 0.08 | 121,875 ± 31,103 |

| 7‐Methylguanosine | 1.090 ± 0.080 | 37 ± 10 | 29,459 ± 8,250 |

| CeNH C42A | |||

| Substrate | k cat (s−1) | K M (µM) | k cat/K M (M −1 s−1) |

| Inosine | 0.024 ± 0.001 | 215 ± 42 | 112 ± 22 |

| Adenosine | 0.023 ± 0.002 | 94 ± 25 | 245 ± 68 |

| Guanosine | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 54 ± 13 | 202 ± 50 |

| p‐NPR | 0.0260 ± 0.0004 | 0.64 ± 0.05 | 40,625 ± 3,234 |

| 7‐Methylguanosine | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 53 ± 8 | 45,283 ± 7,090 |

| CeNH C253A | |||

| Substrate | k cat (s−1) | K M (µM) | k cat/K M (M −1 s−1) |

| Inosine | 0.0043 ± 0.0002 | 343 ± 47 | 13 ± 2 |

| Adenosine | 0.0042 ± 0.0001 | 96 ± 13 | 44 ± 6 |

| Guanosine | 0.0051 ± 0.0003 | 300 ± 65 | 17 ± 4 |

| p‐NPR | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 9 ± 3 | 1,889 ± 639 |

| 7‐Methylguanosine | 1.98 ± 0.05 | 51 ± 5 | 38,823 ± 3,930 |

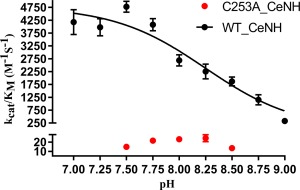

For the C253A mutant, the k cat/K M values for the hydrolysis of inosine, adenosine and guanosine are reduced by a factor of about 120‐fold compared to the wild‐type enzyme. This reduction can nearly completely be attributed to a reduction in the k cat value, by a factor of 47, 100, and 28 for inosine, adenosine and guanosine, respectively. These results show that Cys253 is an important catalytic residue for purine nucleoside hydrolysis. To further pinpoint whether Cys253 plays its catalytic role on the level of leaving group activation, we used two substrate analogues with a highly activated leaving group that consequently do not require additional leaving group activation by the enzyme: p‐nitrophenylriboside (p‐NPR) and 7‐methylguanosine.32, 34, 39 Hydrolysis rates (k cat) of neither of these two substrates are significantly affected by the C253A mutation, allowing us to conclude that Cys253 functions on the level of leaving group activation. This prominent role of Cys253 in leaving group activation in group III NHs is thus reminiscent of the roles of the corresponding histidine and tryptophan residue in group I and group II enzymes, respectively. However, in the mechanism of purine nucleoside hydrolysis by group I IU‐NHs the histidine residue is unfavorably oriented for a direct proton transfer to the N7 atom of the nucleic base. Rather, the proton is relayed to the N7 atom via two tyrosine residues that are highly conserved in IU‐NHs (Tyr225 and Tyr229 in C. fasciculata IU‐NH). In group I pyrimidine‐specific (CU‐NH) enzymes these tyrosine residues are not conserved explaining the low turnover of purine nucleoside in these enzymes, while transfer of a proton from the catalytic histidine to pyrimidine bases is proposed to occur without intermediary residues. In contrast, in our docking model Cys253 seems appropriately oriented for a direct transfer of a proton to the N7 (Fig. 3). In agreement, the tyrosine residues corresponding to Tyr225 and Tyr229 in C. fasciculata IU‐NH are not conserved in group III NHs and correspond to Gly239 and Cys243, respectively in C. elegans NH. We thus propose that Cys253 might act as a general acid by directly protonating the purine leaving group. To further strengthen this hypothesis, we determined the pH dependency of the CeNH‐catalyzed reaction. Since the enzyme was unstable at longer time intervals at pH values below 7 and above 9, we measured k cat/K M using adenosine as a substrate between pH 7 and 9 (Fig. 4). The pH profile shows a clear drop in activity between pH 7 and 9, and the data can be fitted to an equation accounting for the deprotonation of a single group with pK a = 8.25, close to the value expected for a cysteine residue. To identify this group as Cys253, we subsequently determined the pH profile for the C253A mutant. In contrast to the wild‐type enzyme the k cat/K M value for the C253A mutant does not decrease significantly in the same pH range. These data thus further corroborate the role of Cys253 as a general acid required to protonate the N7 of the purine leaving group.

Figure 4.

Effect of pH on the catalytic efficiency (k cat/K M) of CeNH, using adenosine as a substrate. The variation of k cat/K M with pH for wild‐type CeNH and the C253A mutant is shown in black and red, respectively. All data point are the average of three measurements. To allow interpretation of the data for the C253A mutant, the y‐axis is split into two segments with an axis break at the value of 30 M −1 s−1 (the bottom segment of the y‐axis accounts for 15% of the axis while the top segment accounts for 80% of the y‐axis). Fitting of the data for the wild‐type enzyme to an equation accounting for the deprotonation of a single group (see Experimental procedure) yields a pK a value of 8.25.

For the C42A mutant the k cat/K M values for the hydrolysis of inosine, adenosine, and guanosine are reduced by a factor of about 14‐, 22‐, and 10‐fold, respectively, compared to the wild‐type enzyme. Again this is nearly completely due to a decrease in turnover number (kcat), while the mutation leaves KM unaffected. This indicates a significant role of Cys42 in catalysis, yet less pronounced than for Cys253. The observation that the mutation has little or no effect on the hydrolysis of the activated substrates p‐NFR and 7‐methylguanosine allows us to conclude that the catalytic role of Cys42 is situated on the level of leaving group activation, despite a distance of 5.5 Å to the purine base (N3) in our docking model. Such a role would be comparable to the role of Asp40 in the T. vivax group II IAG‐NH, via its interaction with the purine N3.37 A crystal structure of C. elegans NH in complex with a purine nucleoside (analogue) could shed further light on the role of this residue in catalysis.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

Purification of wild‐type and mutant C. elegans NH has been performed as described previously.9 In brief, the open reading frame coding for CeNH was cloned in a pQE‐30 (Qiagen) expression plasmid between restriction sites BamHI and PstI, thus introducing an N‐terminal His6‐tag (pQE30‐CeNH). Point mutants of CeNH were created using the QuickChange site‐directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). E. coli WK6 cells containing pQE30‐CeNH were grown in TB medium in the presence of 50 µg/mL ampicillin at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.7. At that moment recombinant protein production was induced with 100 µM IPTG for the wild‐type protein and 1 mM IPTG for the mutants, and cells were further inoculated overnight at 22°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a buffer containing 20mM Hepes pH 7.5 or 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1M NaCl, 10mM imidazole, 5mM β‐mercaptoethanol, and 1mM CaCl2. The cells were lysed using a cell disruptor system (Constant Systems) and the soluble fraction was loaded on a Ni2+‐sepharose column (GE Healthcare). The column was extensively washed with resuspension buffer containing 60 mM imidazole. Later the protein was eluted with resuspension buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. The eluted fractions were pooled and loaded onto a Superdex 200 gel filtration column with a running buffer containing 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 or Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT.

Enzyme kinetics

Kinetic measurement on wild type CeNH and the C42A and C253A mutants were performed as described earlier.8 All the measurements were performed on a Cary 100 UV‐Vis spectrophotometer at 25°C in a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2. Initial rates of product formation were determined spectrophotometrically at different substrate concentrations using the difference in absorption between the nucleoside and the purine base. The Δε (mM −1 cm−1) values used were: guanosine, −4.0 at 260 nm or 0.16 at 308 nm; adenosine, −1.4 at 276 nm; inosine, −0.92 at 280 nm; 7‐methylguanosine, −4.4 at 258 nm; and p‐nitrophenylriboside, 15 at 400 nm. The data were fitted to the Michaelis‐Menten equation using the GraphPad software.

Analysis of pH data

The pH dependence of k cat/K M of wild‐type CeNH and the C253A mutant was determined between pH 7.0 to 9.0 using adenosine as substrate. k cat/K M values were determined spectrophotometrically by following the full conversion of substrate into products (i.e. at least 90% conversion) at an adenosine concentration below its K M value (15 µM and 30 µM for wild type and C253A CeNH, respectively). Consequently, k cat/K M values were obtained by fitting the progress curves on Eq. (1).40 All measurements were done in triplicate.

| (1) |

where S 0 is the initial substrate concentration and E 0 is the enzyme concentration.

For measurements at different pH values the following buffers (always containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM CaCl2) were used: for pH 7 to 7.5: 20 mM PIPES; for pH 7.5 to 8.5: 20 mM HEPES; for pH 8.5 to 9:20 mM CHES. To obtain the pK a value of wild‐type CeNH, the pH dependence of k cat/K M was fitted to Eq. (2).

| (2) |

Protein crystallization and data collection

The crystal used in this study appeared serendipitously in the cold room in a protein stock containing a high concentration of protein (30 mg/mL) in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT. Crystals were easily observable by eye, but were damaged upon adding cryoprotectant. Therefore, the crystals were mounted in capillaries and X‐ray diffraction data were collected at a resolution of 1.65 Å on beamline X13 (EMBL, DESY, Hamburg) using an X‐ray wavelength of 0.8075 Å at room temperature. To circumvent radiation damage the crystals were translated in the beam at regular time point.

X‐ray crystallography data processing, refinement, and structure analysis

X‐ray diffraction data were processed in DENZO41 and further scaled and merged using SCALEPACK. Subsequently, intensities were converted to structure factors using TRUNCATE.42 The coordinates of a T. b. brucei IG‐NH (pdb 3fz0) subunit, with all residues truncated to alanines using CHAINSAW,43 were used as a search model to solve to structure of CeNH by molecular replacement using PHASER.44, 45, 46 The solution from molecular replacement was subjected to automated model building using the ARP‐WARP online server.47, 48, 49 The model obtained after ARP‐WARP was further built and refined with COOT50 and REFMAC,51, 52, 53 respectively. The anisotropic motion within the molecule was refined with six TLS groups per subunit.54 The final model contained two CeNH protomers, a Ca2+ ion, and a Tris molecule bound to each active site and 376 water molecules in the asymmetric unit. An R‐factor of 13.72% (R‐free = 15.40%) was obtained after the final round of refinement. During refinement, the quality of the model was monitored by MOLPROBITY.55 The quaternary structure was analyzed using PISA within the CCP4I program package.46

SAXS data collection and analysis

Small angle X‐ray scattering (SAXS) data for wild‐type CeNH were collected at the home source using a Rigaku BioSAXS‐2000 instrument. Immediately prior to data collection, the samples were loaded on a Superdex S200 10/300 column using 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 1M NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM DTT as a running buffer and the elution fractions were concentrated separately. Scattering intensities were collected on samples of 70 µL containing the protein at a concentration of 1.5, 4, and 8 mg/mL. The radial averaging and the buffer subtraction was performed using the Rigaku SAXSLab software. The averaged data were later processed using the ATSAS software package.56 The molecular mass of the scattering particle was derived with the Q R method.57 Calculation of the dimensionless Kratky plot and the probability distribution curve was done using the ATSAS program GNOM,58 and CRYSOL was used for calculation of the theoretical scattering profile of the crystal structure.59 Before comparing the theoretical scattering curve obtained from the crystal structure to the experimental profile, missing regions of subunit A and B along with the N‐terminal his‐tag were modeled using the program MODELLER within CHIMERA.60

Substrate docking

The crystal structure of CeNH was preprocessed with AutoDock61 tools to remove all the solvent and ligand molecules (i.e. Tris and water molecule). Polar hydrogen and Kollman charges were added and the files were converted to PDBQT format. The coordinates of inosine, which was used for docking, were obtained from the crystal structure of the YeiK‐inosine complex (PBD 3B9X). Similar to the protein, polar hydrogens were added to the ligand molecule. The ribose moiety was constrained in the C4′ endo conformation, that has generally been found in nucleosides bound to NHs, while the torsion angles around the C1′‐N9 and C4′‐C5′ bonds were allowed to be rotatable during the docking procedure. The docking space was constrained by defining a grid space covering the active site and the nearby region. The conformation of active site residues was kept rigid during docking. The calculations were performed using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and a maximum of 20 conformers. The structure with the minimum energy is used to show interaction with the active site. The Ca2+ atom was kept at its original position in the final structure. Redocking experiment of inosine to the active site of Yeik, and docking of inosine to CeNH starting from a trans conformation, using exactly the same approach has also been performed to validate the accuracy of the AutoDock method (not shown).

Sequence and structural alignment

Sequences of NHs belonging to homology group I, group II, and group III were obtained from the NCBI protein sequence database. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with the Clustal Omega software using the default parameters.62 The sequence alignment were rendered using ESPript 3.0 to show the conservation of residues among the three groups as well as within each group. ENDscript was used to generate a Sausage representation of CeNH by mapping the spatial rmsd values between the individual Cα atoms of the CeNH structure and structures of other NHs available in the PDB.36

Conclusions

In the current article, we present the first structural information on a nucleoside hydrolase belonging to sequence homology group III. We solved the X‐ray crystal structure of the purine‐specific nucleoside hydrolase from the multicellular eukaryotic nematode C. elegans to 1.65 Å resolution. Unlike purine‐specific NHs belonging to group II, which are dimeric, the group III C. elegans NH is a homotetramer, suggesting that the substrate specificity of NHs is independent of their oligomeric states. The crystal structure shows two cysteine residues that point into the active site, Cys42 and Cys253, with the latter corresponding to the hallmark cysteine for group III NHs. Substrate docking suggests that Cys253 is properly oriented to act as a proton donor to the N7 of the purine ring, while Cys42 is located 5.5 Å away from the N3 atom of the purine ring. A site‐directed mutagenesis analysis combined with enzyme kinetics shows that Cys253 plays an important role in catalysis via leaving group activation, while Cys42 has a more moderate contribution to leaving group activation. In addition, pH analysis identifies Cys253 as the general acid in the enzyme‐catalyzed reaction. This role of Cys253 in direct protonation of the leaving group differs from the proposed role of the corresponding histidine in group I enzymes, which use a His‐Tyr‐Tyr catalytic triad to protonate the N7 atom, and of the corresponding tryptophan in group II enzymes that increases the N7 pK a by aromatic stacking. Our findings thus present new insights in the way this sequence homology group of NHs achieves activation of the purine leaving group.

Accession numbers

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with accession code 5MJ7.

Supporting information

Supporting Information 1

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the staff of the EMBL at de DESY synchrotron (Hamburg, Germany) for help with data collection and Stefan De Vos for contributions to initial stages of this work.

Statement in layman's terms: Nucleoside hydrolases (NH) catalyze the hydrolysis of the N‐glycoside bond in ribonucleosides. In parasitic protozoa, including Leishmania and Trypanosoma species, these enzymes have been pursued as drug targets, while their role in bacteria and higher eukaryotes remains unclear. NHs have been classified in three homology groups. We report the first structure of a group III NH and reveal the catalytic role of two group III‐specific cysteine residues.

References

- 1. Pugmire MJ, Ealick SE (2002) Structural analyses reveal two distinct families of nucleoside phosphorylases. Biochem J 25:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Versées W, Steyaert J (2003) Catalysis by nucleoside hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 13:731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller RL, Sabourin CLK, Krenitsky TA (1984) Nucleoside hydrolases from Trypanosoma cruzi . J Biol Chem 259:5073–5077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kopecna M, Blaschke H, Kopecny D, Vigouroux A, Koncitikova R, Novak O, Kotland O, Strnad M, Morera S, von Schwartzenberg K (2013) Structure and function of nucleoside hydrolases from Physcomitrella patens and maize catalyzing the hydrolysis of purine, pyrimidine, and cytokinin ribosides. Plant Physiol 163:1568–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giabbai B, Degano M (2004) Crystal structure to 1.7 Å of the Escherichia coli pyrimidine nucleoside hydrolase YeiK, a novel candidate for cancer gene therapy. Structure 12:739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petersen C, Møller LB (2001) The RihA, RihB, and RihC ribonucleoside hydrolases of Escherichia coli. Substrate specificity, gene expression, and regulation. J Biol Chem 276:884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muzzolini L, Versées W, Tornaghi P, Van Holsbeke E, Steyaert J, Degano M (2006) New insights into the mechanism of nucleoside hydrolases from the crystal structure of the Escherichia coli YbeK protein bound to the reaction product. Biochemistry 45:773–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Porcelli M, Concilio L, Peluso I, Marabotti A, Facchiano A, Cacciapuoti G (2008) Pyrimidine‐specific ribonucleoside hydrolase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus–biochemical characterization and homology modeling. FEBS J 275:1900–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Versées W, Holsbeke E, DeVos S, Zegers I, Steyaert J (2003) Cloning, preliminary characterization and crystallization of nucleoside hydrolases from Caenorhabditis elegans and Campylobacter jejuni . Acta Crystallogr Sect D59:1087–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kurtz JE, Exinger F, Erbs P, Jund R (2002) The URH1 uridine ribohydrolase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Curr Genet 41:132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ribeiro JMC, Valenzuela JG (2003) The salivary purine nucleosidase of the mosquito, Aedes aegypti . Insect Biochem Mol Biol 33:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Estupiñán B, Schramm VL (1994) Guanosine‐inosine‐preferring nucleoside N‐glycohydrolase from Crithidia fasciculata . J Biol Chem 269:23068–23073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parkin DW, Horenstein BA, Abdulah DR, Estupiñán B, Schramm VL (1991) Nucleoside hydrolase from Crithidia fasciculata: metabolic role, purification, specificity, and kinetic mechanism. J Biol Chem 266:20658–20665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Degano M, Gopaul DN, Scapin G, Schramm VL, Sacchettini JC (1996) Three‐dimensional structure of the inosine‐uridine nucleoside N‐ribohydrolase from Crithidia fasciculata. Biochemistry 35:5971–5981. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Versées W, Decanniere K, Pellé R, Depoorter J, Brosens E, Parkin DW, Steyaert J (2001) Structure and function of a novel purine specific nucleoside hydrolase from Trypanosoma vivax . J Mol Biol 307:1363–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arivett B, Farone M, Masiragani R, Burden A, Judge S, Osinloye A, Minici C, Degano M, Robinson M, Kline P (2014) Characterization of inosine‐uridine nucleoside hydrolase (RihC) from Escherichia coli . Biochim Biophys Acta 1844:656–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Versées W, Goeminne A, Berg M, Vandemeulebroucke A, Haemers A, Augustyns K, Steyaert J (2009) Crystal structures of T. vivax nucleoside hydrolase in complex with new potent and specific inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goeminne A, Berg M, McNaughton M, Bal G, Surpateanu G, Van der Veken P, Prol S, De Versées W, Steyaert J, Haemers A, Augustyns K (2008) N‐Arylmethyl substituted iminoribitol derivatives as inhibitors of a purine specific nucleoside hydrolase. Bioorganic Med Chem 16:6752–6763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berg M, Kohl L, Van Der Veken P, Joossens J, Al‐Salabi MI, Castagna V, Giannese F, Cos P, Versées W, Steyaert J, Grellier P, Haemers A, Degano M, Maes L, De Koning HP, Augustyns K (2010) Evaluation of nucleoside hydrolase inhibitors for treatment of african trypanosomiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1900–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hammond DJ, Gutteridge WE (1984) Purine and pyrimidine metabolism in the Trypanosomatidae . Mol Biochem Parasitol 13:243–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cui L, Rajasekariah GR, Martin SK (2001) A nonspecific nucleoside hydrolase from Leishmania donovani: implications for purine salvage by the parasite. Gene 280:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nico D, Claser C, Borja‐Cabrera GP, Travassos LR, Palatnik M, Soares IDS, Rodrigues MM, Palatnik‐de‐Sousa CB (2010) Adaptive immunity against Leishmania nucleoside hydrolase maps its C‐terminal domain as the target of the CD4+ T cell‐driven protective response. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hudspeth EM, Wang Q, Seid CA, Hammond M, Wei J, Liu Z, Zhan B, Pollet J, Heffernan MJ, McAtee CP, Engler DA, Matsunami RK, Strych U, Asojo OA, Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME (2016) Expression and purification of an engineered, yeast‐expressed Leishmania donovani nucleoside hydrolase with immunogenic properties. Hum Vaccin Immunother 12:1707–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Minici C, Cacciapuoti G, Leo E, De, Porcelli M, Degano M (2012) New determinants in the catalytic mechanism of nucleoside hydrolases from the structures of two isozymes from Sulfolobus solfataricus Biochemistry 2012;51:4590–4599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Belenky P, Christensen KC, Gazzaniga F, Pletnev AA, Brenner C (2009) Nicotinamide riboside and nicotinic acid riboside salvage in fungi and mammals: quantitative basis for Urh1 and purine nucleoside phosphorylase function in NAD+ metabolism. J Biol Chem 284:158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang L, He X, Liu G, Tan H (2008) The role of a purine‐specific nucleoside hydrolase in spore germination of Bacillus thuringiensis . Microbiology 154:1333–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Redmond C, Baillie LWJ, Hibbs S, Moir AJG, Moir A (2004) Identification of proteins in the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis . Microbiology 150:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jung B, Hoffmann C, Möhlmann T (2011) Arabidopsis nucleoside hydrolases involved in intracellular and extracellular degradation of purines. Plant J 65:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parkin DW (1996) Purine‐specific nucleoside N‐ribohydrolase from Trypanosoma brucei purification, specificity and kinetic metabolism. J Biol Chem 271:21713–21719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pelle R, Schramm VL, Parkin DW (1998) Molecular cloning and expression of a purine‐specific N‐ribohydrolase from Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Sequence, expression, and molecular analysis. J Biol Chem 273:2118–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janion C, Lovtrup S (1963) Pyrimidine nucleoside hydrolase in Thermobacterium acidophilum . Acta Biochim Pol 10:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gopaul DN, Meyer SL, Degano M, Sacchettini JC, Schramm VL (1996) Inosine‐uridine nucleoside hydrolase from Crithidia fasciculata. Genetic characterization, crystallization, and identification of histidine 241 as a catalytic site residue. Biochemistry 35:5963–5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iovane E, Giabbai B, Muzzolini L, Matafora V, Fornili A, Minici C, Giannese F, Degano M (2008) Structural basis for substrate specificity in group I nucleoside hydrolases. Biochemistry 47:4418–4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Versées W, Loverix S, Vandemeulebroucke A, Geerlings P, Steyaert J (2004) Leaving group activation by aromatic stacking: an alternative to general acid catalysis. J Mol Biol 338:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loverix S, Geerlings P, McNaughton M, Augustyms K, Vandemeulebroucke A, Steyaert J, Versées W (2005) Substrate‐assisted leaving group activation in enzyme‐catalyzed N‐glycosidic bond cleavage. J Biol Chem 280:14799–14802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robert X, Gouet P (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res 42:320–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Versées W, Barlow J, Steyaert J (2006) Transition‐state complex of the purine‐specific nucleoside hydrolase of T. vivax: enzyme conformational changes and implications for catalysis. J Mol Biol 359:331–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Degano M, Almo SC, Sacchettini JC, Schramm VL (1998) Trypanosomal nucleoside hydrolase. A novel mechanism from the structure with a transition‐state inhibitor. Biochemistry 37:6277–6285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mazzella LJ, Parkin DW, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Schramm VL (1996) Mechanistic diagnoses of N‐ribohydrolases and purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J Am Chem Soc 118:2111–2112. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fersht AR, Renard M (1974) pH Dependence of chymotrypsin catalysis. Appendix. Substrate binding to dimeric α‐chymotrypsin studied by x‐ray diffraction and the equilibrium method. Biochemistry 13:1416–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Otwinowski Z, Minor W (1997) Processing of X‐ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. French S, Wilson K (1978) On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallogr Sect A 34:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stein N (2008) CHAINSAW: a program for mutating pdb files used as templates in molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallograllogr 41:641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 44. McCoy AJ (2006) Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr Sect D63:32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McCoy AJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallograllogr 40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr Sect D67:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A (2008) Automated macromolecular model building for X‐ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc 3:1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cohen SX, Richard J, Francisco J, Lamzin VS, Gerard J (2004) Towards complete validated models in the next generation of ARP/wARP research papers. Acta Crystallogr Sect D 60:2222–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Perrakis A, Harkiolaki M, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS (2001) ARP/wARP and molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr 57:1445–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: Model‐building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D 60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum‐likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr Sect D53:240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vagin AA, Roberto A, Lebedev AA, Mcnicholas S (2004) REFMAC5 dictionary: organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use research papers. Acta Crystallogr Sect D 60:2184–2195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53. Murshudov GN, Skubák P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr Sect D67:355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr Sect D57:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Davis IW, Leaver‐Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC (2007) MolProbity: all‐atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res 35:375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Petoukhov MV, Franke D, Shkumatov AV, Tria G, Kikhney AG, Gajda M, Gorba C, Mertens HDT, Konarev PV, Svergun DI (2012) New developments in the ATSAS program package for small‐angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallograllogr 45:342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rambo RP, Tainer JA (2013) Accurate assessment of mass, models and resolution by small‐angle scattering. Nature 496:477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Svergun DI (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect‐transform methods using perceptual criteria. J Appl Crystallogr 25:495–503. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barberato C, Koch MHJ, Molecular E, Outstation H (1995) CRYSOL ‐ a program to evaluate X‐ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J Appl Crystallogr 28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Martí‐Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sánchez R, Melo F, Šali A (2000) Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 29:291–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Morris G, Huey R (2009) AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 30:2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high‐quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information 1