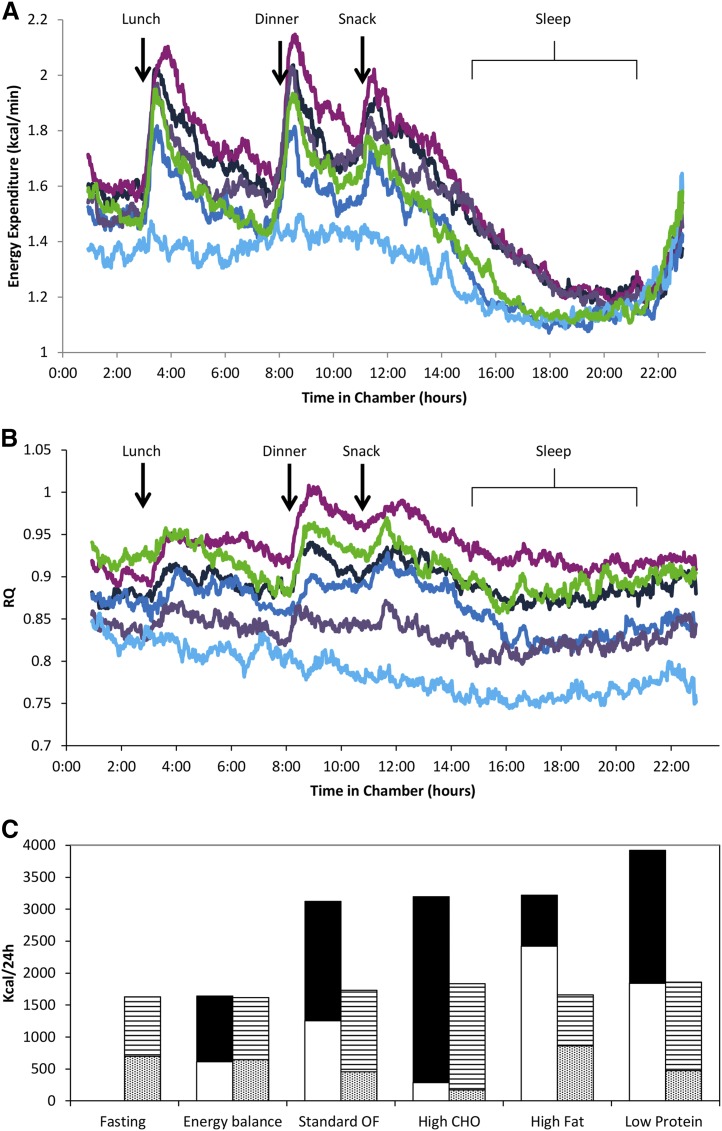

Figure 2.

Graphic of (A) EE and (B) related RQ of each different dietary intervention and of (C) mean carbohydrate (CHO) and lipid intake and oxidation. (A) EE/min and (B) RQ data series over 23.25 hours during all dietary interventions and compared with EB (shown in dark blue). The EE/min and temporal RQ during overfeeding (OF) are shown with the standard OF diet (n = 64; 50% CHO, 30% fat, and 20% protein) in black; the high-CHO OF diet (n = 63; 75% CHO, 5% fat, and 20% protein) in fuchsia; the high-fat OF diet (n = 63; 20% CHO, 60% fat, and 20% protein) in purple; and the low-protein OF diet (n = 62; 51% CHO, 46% fat, and 3% protein) in green. The EE/min and RQ during fasting (n = 64) are shown in light blue. The 0:00 time period indicates entry into the respiratory chamber (∼1 hour after consuming breakfast); lunch was given at the 3-hour mark, dinner at the 8-hour mark, and a snack at the 11-hour mark. Participants were asked to be in bed from the 15-hour mark to at least the 21-hour mark in the chamber, and to limit unnecessary activity throughout the 24-hour period. All trajectories were different from all other trajectories (P < 0.0001). (C) Graphic representation of mean for CHO intake in black, lipid intake in white, carbox in horizontal stripes, and lipox in dots during the different diets. Overall, despite the increase in MO following the respective increase in the amount of each specific macronutrient ingested, the amount of energy burned was less than energy ingested. Note that for high-fat OF, on average, all of the CHO given was oxidized.