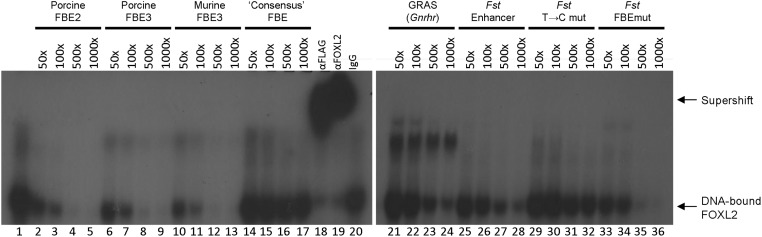

Figure 3. FOXL2 binds regulatory sequences in Fshb, Gnrhr, and Fst.

Nuclear extracts from heterologous Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing murine FLAG-FOXL2 were incubated with a radiolabeled double-stranded probe corresponding to −185/−145 of the porcine Fshb promoter, which contains the high-affinity FBE2 (see Figure 2). As reported previously (43), FOXL2 forms a specific complex with the probe when resolved on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (lane 1; labeled at extreme right). The complex contains FLAG-FOXL2 as indicated by the supershifted complexes observed when antibodies against the FLAG tag (lane 18) or FOXL2 (lane 19) are included in the mix (labeled at right). Binding is dose dependently competed when an unlabeled form of the same probe is included at 50-, 100-, 500-, or 1000-fold molar excess relative to the radiolabeled probe (lanes 2–5). Similarly, unlabeled double-stranded DNA probes containing FBE3 in pig (lanes 6–9) or mouse (lanes 10–13), GRAS from murine Gnrhr (lanes 21–24), the rat Fst intronic enhancer (lanes 25–28), or the Fst enhancer containing mutations in the putative FBE (lanes 33–36) also compete for binding, indicating that they too contain intact FOXL2-binding sites. A probe containing the putative consensus FOXL2-binding site (lanes 14–17) (Ref. 91) fails to compete for binding, suggesting that it lacks a true FOXL2 binding sequence. A Fst enhancer probe containing a mutation in what we predict to be the actual FBE is impaired in its ability to compete for binding (lanes 29–32). Probe sequences (sense strand only) are shown, putative FBEs are underlined, and mutated base pairs are shown in lower case: porcine FBE2, TTATTTTTCCTGTTCCACTGTGTTTAGACTACTTTAGTAAG; porcine FBE3, CCTGTCTATCTAAACACTGATTCACTTACAG; murine FBE3, GCTTGATCTCCCTGTCCGTCTAAACAATGATTCCCTTTCAG; consensus FBE, CCTGTCACGGTCAAGGTCACTATCACTCAC; GRAS, TTTTGTATCTGTCTAGTCACAACAGTTTTT; Fst, GCTGCACGTGTTGTGTCTGGGTCACTGGTAACTGACATTGATATGGCTAG; Fst T->C, GCTGCACGcGTTGTGTCTGGGTCACTGGTAACTGACATTGATATGGCTAG; and Fst FBEmut, GCTGCACGTGTTGTGTCTGGGTCACTGGTAACTGACAcaGcTATGGCTAG.