Introduction

KEY TEACHING POINTS

|

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a cardiac arrhythmia that frequently presents in childhood and is characterized by a prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram (ECG) in combination with syncope or cardiac arrest; these findings often occur in the setting of physical or emotional stress or abrupt auditory stimuli.1 The genetics of LQTS have been well documented over the past decade, with the identification of ≥15 genes corresponding to different disease subtypes.2

Typically, LQTS type 1 presents as 1 of 2 clinical syndromes: 1 with a severe arrhythmia phenotype and often congenital deafness due to homozygous or compound heterozygous mutation of KNCQ1 (including the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome3) and the other with isolated arrhythmias of variable severity due to heterozygous KCNQ1 mutation (originally known as the Romano-Ward syndrome4).

This complex inheritance pattern relates partly to the multimeric nature of the Kv7.1 channel, where a single aberrant subunit can disrupt the function of an entire channel, resulting in a dominant-negative effect by which a heterozygous mutation can impair physiological function by >50%. However, the dominant-negative effect is not universal among KCNQ1 mutations, and other mutation patterns are recognized (such as nonsense mutations, which can manifest as disease-causing in the heterozygous state, albeit often with a milder phenotype).

Here we present a case of a patient with severe LQTS phenotype due to homozygous nondominant-negative mutation in the KCNQ1 gene, whose heterozygous family members are unaffected.

Case Report

An 8-year-old boy presented because of recurrent loss of consciousness and abnormal ECG. His parents were from Yemen, and care was substantially fragmented by linguistic/cultural barriers and frequent travel overseas. He had fetal and neonatal bradycardia, although no diagnosis was made at that time. Starting at approximately 3 years of age, he had frequent exertional collapse followed by shaking movements, which led to a near-drowning episode. Seizures were diagnosed (in Yemen) and treated with sodium valproate, which reportedly eliminated the episodes.

On his return to the United States, he was switched to divalproex sodium and the episodes returned. However, the neurology service could not confirm a primary seizure disorder, and cardiac evaluation showed QTc prolongation. He was started on atenolol (with partial relief) and was referred to electrophysiology clinic.

On the basis of clinical evaluation, a diagnosis of LQTS was made, and the patient was switched to nadolol, provided with an automatic external defibrillator, and sent for genetic testing. Both syncope and “seizure” episodes resolved completely on nadolol (currently 20 mg in the morning and 10 mg at night, providing 1.25 mg/kg/d); other therapies (including implanted defibrillator and left cardiac sympathetic denervation) were discussed but declined by the family. The divalproex sodium was discontinued without any recurrence of symptoms.

Retrospective review of prior ECGs from various sources revealed variable repolarization abnormality and QTc prolongation. At 5 weeks of age, there was marked T-wave flattening with QTc of 480 ms. At 3 years, there was lateral T-wave inversion with QTc of 530 ms (Figure 1A). At 8 years, there were nonspecific T-wave changes with QTc of 450 ms at baseline (Figure 1B) but evolving dramatically with stress test (QTc of 560 ms at peak exercise and 630 ms in recovery associated with diffuse bizarre repolarization abnormality including macroscopic T-wave alternans) (Figure 2). Results of physical examination and echocardiogram were normal. There were no concerns of hearing loss from the patient’s parents, school, or primary care provider, and speech development was normal.

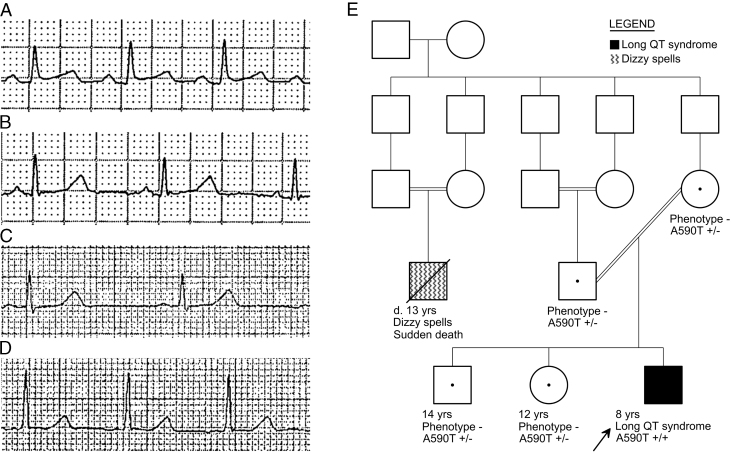

Figure 1.

Resting electrocardiograms from the proband. A: At age 3 years, with QTc 530 ms and marked repolarization abnormality. B: At age 8 years, with QTc 450 ms and nonspecific flattening of T waves.

Figure 2.

Exercise stress test excerpts from the proband at age 8 years. A: At peak exercise, showing marked repolarization abnormality, QT prolongation, and T-wave alternans. B: At 4 minutes of recovery, showing even further QT prolongation with subtle T-wave alternans.

Commercial genetic testing (traditional sequencing panel) revealed homozygous KCNQ1 c.1768G>A p.Ala590Thr (hereafter A590T). No significant variants were identified in KCNH2, SCN5A, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNJ2, CAV3, SCN4B, SNTA1, nor KCNJ5, nor in selected exons of ANK2, CACNA1C, nor AKAP9. The KCNQ1 variant was classified by the laboratory as a deleterious mutation on the basis of location in the Subunits Assembly Domain, presence in several unrelated probands, absence from large control populations, and functional characterization as abnormal in the literature.

Cascade genetic testing identified heterozygous mutations in both parents and both siblings, although all 4 were asymptomatic, with normal QTc intervals and T-wave morphologies (Figure 3A–3D), including normal repolarization response to exercise in the brother. Consanguinity was initially denied, but careful re-exploration of family history in light of the genetic testing results revealed a complex blood relationship between the parents, as well as a distant cousin with sudden death around age 13 years (preceded by a history of dizzy spells) also in the setting of consanguinity (Figure 3E). The proband’s parents were asked to contact relatives in Yemen and recommend cardiac evaluation; no results were available as of this writing.

Figure 3.

Resting electrocardiogram excerpts from the proband’s asymptomatic relatives, A: father, B: mother, C: brother, and D: sister, each showing normal QTc intervals in lead II (420, 420, 400, 410 ms, respectively). E: Abbreviated pedigree indicating the proband (arrow), the complex blood relationship between the proband’s parents, and a cousin who had died suddenly, also born to consanguineous parents. The pedigree is complete for the immediate families of the 2 symptomatic members but omits the very numerous more-distant relatives because of lack of detailed information and for simplicity (eg, the founding couple reportedly had at least 9 children, of which only 5 are shown).

Discussion

LQTS most often demonstrates autosomal dominant inheritance (ie, Romano-Ward syndrome).1 The gene mutations in Romano-Ward syndrome produce disease via a number of mechanisms, including a decrease in channel number (due to haploinsufficiency or impaired subunit trafficking to the cell membrane) and alteration in channel function (often severely, when the coassembly of defective and wild-type subunits can produce a dominant-negative effect).1 Although not commonly identified with LQTS, in principle, a deleterious mutation could present in a classic autosomal recessive pattern if dominant-negative effects were lacking, and indeed this concept has been validated in functional5 and clinical6 reports.

The family here reported is affected by the KCNQ1 A590T mutation. The KCNQ1 gene encodes 1 subunit of the potassium channel Kv7.1 responsible for IKs, the slow-activating delayed rectifier potassium current. The KCNQ1 A590T mutation occurs in a portion of the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail considered important for subunit-specific tetramerization, membrane trafficking, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate signaling through Yotiao interactions. Functional characterization demonstrated the major impact of this mutation to be decreased membrane trafficking with resulting decreases in Kv7.1 cell surface expression and IKs current amplitude.7 Kinoshita et al7 showed that A590T IKs function in vitro was rescued when coexpressed with wild-type KCNQ1, predicting that heterozygous patients might have a very mild phenotype, whereas homozygous patients could have a severe phenotype. However, they had only a single heterozygous patient for clinical correlation, and prior reports of isolated A590T heterozygotes offered little additional clinically relevant detail.8 Our family supports this understanding with 4 more heterozygotes and the first reported homozygote.

Although an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern is the most common presentation of LQTS, other patterns are possible.9 When gene variants lacking overt phenotype in the heterozygous state are identified in control populations, their pathogenicity may be underappreciated. The potential for such variants to increase the risk of arrhythmia in the setting of QT-prolonging medication is intriguing but yet to be fully understood.10

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Laura Fischer, MS, CGC, Joseph Orie, MD, Rebecca Pratt, MD, Laurie Sadler, MD, and Donald Switzer, MD for assistance in the care of this family, and Koshi Kinoshita, PhD, Yukiko Hata, PhD, and Naoki Nishida, MD, PhD, from the University of Toyama for thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Schwartz P.J., Crotti L., Insolia R. Long-QT syndrome: from genetics to management. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5(4):868–877. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakano Y., Shimizu W. Genetics of long-QT syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2016;61(1):51–55. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jervell A., Lange-Nielsen F. Congenital deaf-mutism, functional heart disease with prolongation of the Q-T interval and sudden death. Am Heart J. 1957;54(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(57)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romano C., Gemme G., Pongiglione R. Rare cardiac arrhythmia of the pediatric age II, syncopal attacks due to paroxysmal ventricular fibrillation [in Italian] Clin Pediatr (Bologna) 1963;45:656–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi L., Priori S.G., Napolitano C., Surewicz K.A., Dennis A.T., Memmi M., Schwartz P.J., Brown A.M. Mechanisms of I(Ks) suppression in LQT1 mutants. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(6):H3003–H3011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priori S.G., Schwartz P.J., Napolitano C., Bianchi L., Dennis A., De Fusco M., Brown A.M., Casari G. A recessive variant of the Romano-Ward long-QT syndrome? Circulation. 1998;97(24):2420–2425. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinoshita K., Komatsu T., Nishide K. A590T mutation in KCNQ1 C-terminal helix D decreases IKs channel trafficking and function but not Yotiao interaction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;72:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lupoglazoff J.M., Denjoy I., Villain E., Fressart V., Simon F., Bozio A., Berthet M., Benammar N., Hainque B., Guicheney P. Long QT syndrome in neonates: conduction disorders associated with HERG mutations and sinus bradycardia with KCNQ1 mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(5):826–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhuiyan Z.A., Wilde A.A. IKs in heart and hearing, the ear can do with less than the heart. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;692:141–143. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novotný T., Kadlecová J., Papousek I. Mutational analysis of LQT genes in individuals with drug induced QT interval prolongation [in Czech] Vnitr Lek. 2006;52(2):116–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]