Introduction

KEY TEACHING POINTS

|

Heteromeric KV7.1/KCNE1 channels conduct the cardiac repolarizing current IKs that is crucial in the stress-mediated adaptation of the myocyte action potential duration in a rate-dependent way. Stress reactions via both β-adrenergic stimulations1, 2, 3 and cortisol release along the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis4, 5, 6 are known to activate IKs channels. IKs activation is important to increase repolarization forces at higher heart rates to counteract depolarizing cardiac calcium currents.7 Impaired IKs function can result from gene mutations, from pharmacological intervention,8 and/or from myocardial infections with Coxsackie virus B3, as shown in a mouse model.9 Unbalanced ion fluxes during cardiac action potentials can thus lead to cardiac arrhythmias and potentially cause sudden cardiac death.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

KV7.1 α-subunits alone form tetrameric KV channels through an assembly domain in the intracellular C-terminus of the channel protein.16, 17 Furthermore, KV7.1 channels coassemble with KCNE1 (minK) and the two engage in dynamic interactions. The exact stoichiometry is under intense debate and, so far, it is largely unknown whether the KV7.1/KCNE1 stoichiometry is regionally variable in different tissues or subregions of the heart.18

Mutations in the gene encoding either KV7.1 (KCNQ1) or KCNE1 (KCNE1) have been associated with many inherited forms of cardiac arrhythmia.19 In most of the cases, loss-of-function mutations in KCNQ1 cause long QT syndrome (LQTS) and associated ventricular arrhythmias termed torsades de pointes.20 In contrast, gain-of-function mutations in IKs channels are relatively rare and lead to the opposite electrocardiogram (ECG) phenotype, short QT syndrome (SQTS), and in some cases atrial fibrillation.21, 22, 23, 24

KCNE1 harbors one transmembrane segment, an extracellular N-terminus, and an intracellular C-terminus. Several interaction points between KV7.1 and KCNE1 have been identified on the extracellular side of the channel complex.25 Furthermore, a recent study of the positioning between the KCNE1 extracellular domain structure26, 27 and KV7.128 predicted several interaction sites.

In this study, we present a novel SQTS mutation, A287T, and elucidate its pathophysiological mechanism to provide novel insight into the α–β interaction.

Methods

Clinical characterization

All probands who participated in the study gave written informed consent in accordance with the last version of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association and R281) and with recommendations by the local ethics committee.

We performed clinical and genetic investigations as previously described.29 Briefly, ECG analyses were performed using conventional 12-lead ECG recordings and standard lead positions (paper speed 50 mm/s), and heart rate–corrected QT intervals (QTc) were calculated by Bazett’s30 and by Fridericia’s formula.31 Genomic DNA was isolated from blood lymphocytes by standard semiautomatic procedures (QIAcube protocols; Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). A stepwise sequencing approach was initiated by investigating the major LQTS and SQTS genes, KCNQ1 (LQT1 or SQT2, GenBank Accession No. NM_000218.2; LRG_287) and KCNH2 (LQT2 or SQT1, NM_000238.3; LRG_288). Mutation nomenclature was done with the use of the Alamut annotation software (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) and annotation was in accordance with the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/). The control group consisted of an in-house sample (n = 380 healthy, unrelated controls). Furthermore, variants were investigated for presence in the Exome Sequencing Project population of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) and in ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/).

In silico analysis and nucleotide variant classification

Potential pathogenic impact of missense variants was determined as described before.29 We used six different pathogenicity prediction tools, namely KvSNP (http://www.bioinformatics.leeds.ac.uk/KvDB/htdocs/php/KvSNP.php), PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), Mutation taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), MutPred (http://mutpred.mutdb.org/), and SNPs&GO (http://snps-and-go.biocomp.unibo.it/snps-and-go/). To determine the evolutionary protein conservation of mutated residue sites, an orthologous alignment was performed using ClustalW.

Molecular biology

Oocyte expression plasmid constructs hKV7.1 (GenBank Accession No. NM_000218) in pXOOM and hKCNE1 (NM_000219) in pSP64 have been previously described.25, 32 Standard site-directed mutagenesis was performed to generate the mutants A287T, A287C, A287D, A287E, A287K, A287Q, A287S, T322A, and T322M. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (Macrogen Inc, Seoul, South Korea). The plasmids were linearized using NheI for hKV7.1 and EcoRI for hKCNE1. In vitro synthesis of cRNA was done using the T7 or SP6 mMessage mMachine kits (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Oocytes were injected with 12 ng of KV7.1 wild-type (KV7.1-WT) or mutant cRNA and 2.4 ng of KCNE1-WT cRNA corresponding to a 6:1 molar ratio. For Western blot analysis intact injected and uninjected/control oocytes (each with 10 oocytes per preparation) were homogenized with a P200 pipette in HbA buffer (in mM: 20 Tris-HCl, 5 MgCl2, 6H2O, 5 NaH2PO4, H2O, 1 EDTA, 80 sucrose, pH 7.4, supplemented with protease inhibitor cOmplete, Roche Lifescience, Mannheim, Germany). After centrifugation for 30 minutes at 16,000g, the supernatants were supplemented with 4 μL sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer (0.8 M β-mercaptoethanol, 6% SDS, 20% glycerol, 25 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% bromphenol blue, pH 6.8) per oocyte. Proteins from homogenized oocytes were separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany). Blots were blocked in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Roti-Block (A151; Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) for at least 1 hour at room temperature. For the detection of KV7.1, membranes were incubated with primary rabbit polyclonal anti–potassium channel KV7.1 antibody (1:100; AB5932; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), which detects a fragment of ~70 kDa. As a loading control, primary mouse monoclonal anti–beta 1 sodium potassium ATPase antibody (1:500; ab2873; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used that recognizes a fragment of ~35 kDa. Secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit IgG (NA934) and anti-mouse IgG (NXA931), both in 1:10,000 dilution (GE Healthcare Life Science, Freiburg, Germany). For verification of protein levels, Ponceau Red staining was performed. Labeled proteins were detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (Immuno Cruz, A1713; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX).

Electrophysiology

Xenopus laevis oocytes were obtained from EcoCyte Bioscience (Castrop-Rauxel, Germany). Oocytes were injected with 12 ng of KV7.1-WT or mutant cRNA and 2.4 ng of KCNE1-WT cRNA. In the case of variable stoichiometry the amounts of cRNA were 12 ng of KV7.1 plus 12 ng of KCNE1 (molar ratio of 1.3:1), plus 2.4 ng of KCNE1 (6:1), plus 1.2 ng of KCNE1 (13:1) or plus 0.12 ng of KCNE1 (130:1). The oocytes were incubated for 3–4 days at ~18°C in Barth’s solution containing (in mM): 88 NaCl, 1.0 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.4 CaCl2, 0.8 MgSO4, 5 Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, supplemented with penicillin-G (63 mg/L), gentamicin (100 mg/L), streptomycin sulfate (40 mg/L), and theophylline (80 mg/L). Standard 2-electrode voltage-clamp (TEVC) recordings were conducted at ~22°C using a Turbo Tec-10CD amplifier (NPI Electronics, Tamm, Germany), Digidata 1322A AD/DA-interface, and pCLAMP 9.0 software (Axon Instruments Inc/Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The recorded data were analyzed with ClampFit 9.0 (Molecular Devices), Prism6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), and OriginPro 9.0 (Additive, Friedrichsdorf, Germany). Recording pipettes were filled with 3 M KCl and had resistances of 0.5–1.0 MΩ. Recording solution ND96 (in mM: 96 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 1.0 CaCl2, 5 HEPES) was used to record standard currents. In the case of high K+ or high Rb+ solutions, 100 mM KCl or 100 mM RbCl were added to ND96 solution. The pH was equilibrated to 7.6 in all recording solutions.

Molecular dynamics simulations

We used the KV7.1/KCNE1 structural model from Xu et al28 and introduced the mutation A287T in all 4 KV7.1 subunits to obtain the mutant channel. Energy minimizations were performed on the WT KV7.1/KCNE1 model and the new KV7.1-A287T/KCNE1 model in parallel using the AMBER03 force field with the identical setting. The models were incorporated into membranes and 0.9 % NaCl and before all-atoms-mobile simulations were performed for 10ns to reach stable conformations using YASARA Structure version 10.1 (YASARA Biosciences GmbH, Vienna, Austria), as previously described.33 Structural analyses were performed using customized scripts based on YASARA scripts md-analyze, md-analyzeres, md-analyzestr, md-analyzemul, and Discovery Studio 4.0 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA). Mathematical and graphical analysis were performed using OriginPro 9.0 (Additive, Friedrichsdorf, Germany).

Results

Clinical and genetic characterization

We followed up on a 16-year-old female patient (family 10919-1) who survived cardiac arrest after ventricular fibrillation. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation after this first cardiovascular symptom was successful and she recovered without a neurologic deficit. There was no evidence for any medications, electrolyte imbalances, or other abnormalities.

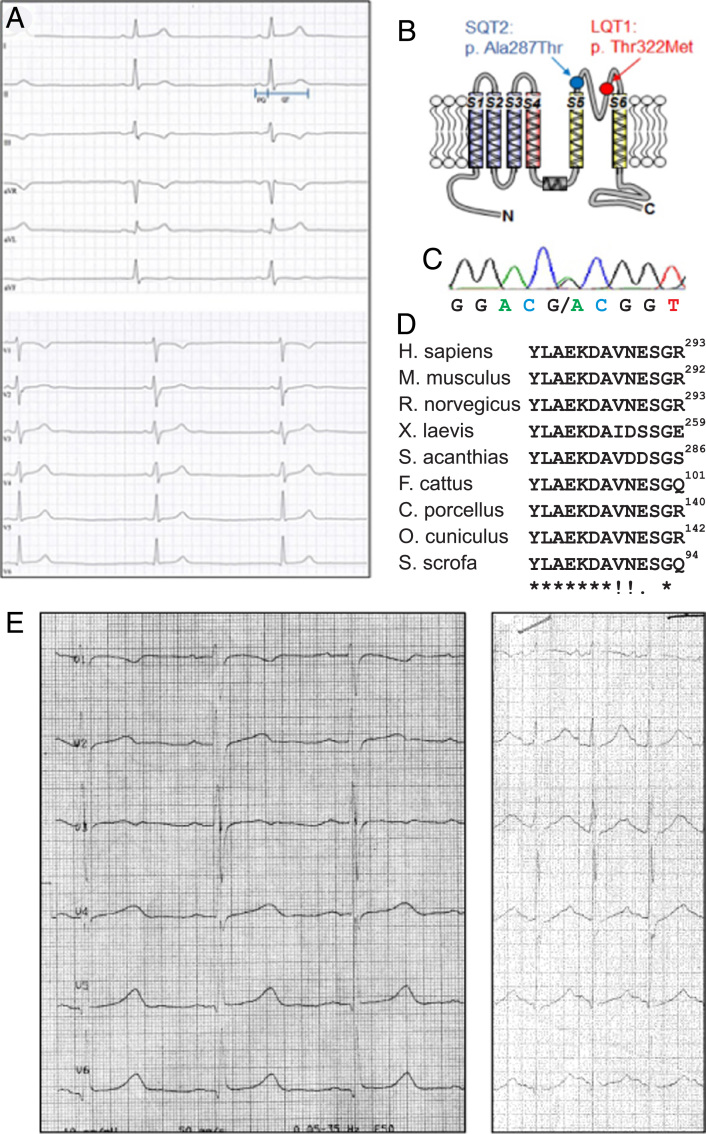

Electrocardiographic findings were shortened QTc (333 ns) intervals. The PQ value was 116 ms and the P-wave and T-wave morphology was normal (ECG, Figure 1A). According to current criteria,34 an SQTS (owing to a QTc <360 ms and cardiac symptoms) was diagnosed. An invasive electrophysiological study failed to induce ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Finally, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted for secondary prophylaxis. During a follow-up of two years, one episode of a supraventricular tachycardia (143 beats per minute) was noticed despite long-term treatment with β-receptor blockers. However, after three years another episode of ventricular fibrillation occurred which was adequately terminated by implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shock. Two other female mutation carriers (mother, aunt) had a normal QT interval and did not show any clinical symptoms.

Figure 1.

Clinical characterization. A: Twelve-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) at 50 mm/s of index patient with SQT: Heart rate of 46/min, normal P-wave duration (82 ms) and QRS duration (96 ms), but PQ interval at the lower limit (116 ms, no pre-excitation) and QT interval of 380 ms, corresponding to a short QTc interval (Bazett’s correction: 333 ms; Fridericia’s correction: 348 ms). No isoelectric ST segment or early repolarization was observed. B: Membrane topology of the predicted KV7.1 protein structure and localization of the two identified mutations. C: Representative electropherogram of index patient with SQT bearing the mutation c.859G>A (p.Ala287Thr) in KCNQ1. D: Multiple-sequence alignment of human Kv7.1 protein (aa 281–293) with corresponding regions of orthologous protein sequences. Identical amino acids are indicated by an asterisk, highly conserved amino acids are indicated by a colon, and semiconserved amino acids are indicated by a dot in the lower lane. The mutated amino acid residue 287 is highlighted in bold. E: Baseline and exercise ECG of index patient with a heterozygous LQT1 mutation (Thr322Met), showing a borderline QT interval at rest (440–450 ms) and paradoxical prolongation at higher heart rates (up to 480 ms).

Genetic testing in major SQTS genes (KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNJ2) identified a novel heterozygous nucleotide exchange c.859 G>A in exon 7 of the KCNQ1 gene. This mutation predicted an amino acid substitution, p.Ala287Thr (Figure 1B and C). This nonsynonymous variation was absent in controls as well as in the mutation repository underlying the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute GO Exome Sequencing Project. Alanine at amino acid position 287 revealed a high degree of orthologous conservation (Figure 1D). Several pathogenicity prediction programs (KVSNP, SNPs&GO, Mutation taster SIFT, and PolyPhen2) judged this variation uniformly as being deleterious/pathogenic, while MutPred evaluated a lower probability for a deleterious mutation (0.381).

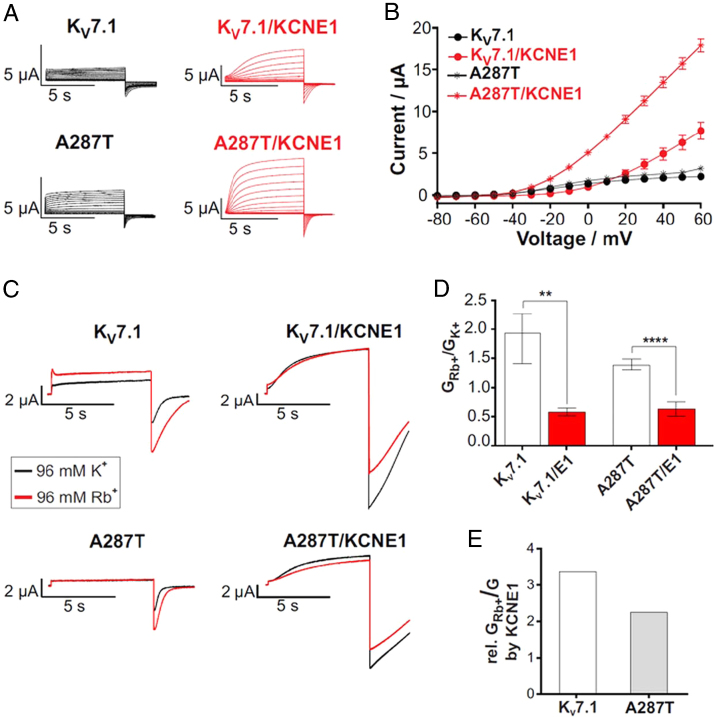

KV7.1-A287T shows a gain-of-function phenotype and affects KV7.1 ion conduction

To elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism, we performed TEVC experiments comparing WT and mutant channels (briefly: KV7.1-A287T) in Xenopus laevis oocytes. As illustrated in Figure 2A and B, KV7.1-A287T exhibited significantly increased peak current amplitudes compared with KV7.1-WT channels. This gain-of-function phenotype was even more pronounced when the channel was coexpressed with its β-subunit KCNE1.

Figure 2.

Heterologous expression of KV7.1-WT and KV7.1-A287T channels in absence and presence of KCNE1 in Xenopus laevis oocytes suggests a gain-of-function of mutant channels associated with altered K+ vs Rb+ sensitivity. A: Representative current traces of KV7.1-WT and mutant KV7.1-A287T (A287T) in absence or presence of KCNE1. Oocytes were injected with 12 ng KV7.1-WT or mutant cRNA and 2.4 ng KCNE1-WT cRNA (molar ratio of 6:1). Currents were elicited with 7-second pulses to potentials of -100 to +60 mV in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of -80 mV. B: Current–voltage relationship of KV7.1 and mutant KV7.1-A287T in absence or presence of KCNE1 (n = 14–33, ± standard error of the mean). C: Representative current traces for KV7.1-WT and the mutant A287T channel elicited by a 7-second pulse to +40 mV pulse and a return to -120 mV. Currents were recorded in high K+ (black trace) and in high Rb+ solution (red trace). D: Tail current amplitudes at -120 mV after a +40 mV activating pulse in high extracellular concentrations of K+ and Rb+ were assessed for homomeric/heteromeric wild-type and mutant channels. GRb+/GK+ are shown (n = 10–14). E: Relations of GRb+Kv7.1/GK+Kv7.1/KCNE1 and GRb+A287T/GK+A287T/KCNE1 (simplified named here as “rel. GRb+/GK+ by KCNE1”; mean data from B were used).

Next, we addressed whether the gain-of-function phenotype may be a result of altered conductance through the selectivity filter (Figure 2C–E). The selectivity filter of KV7.1 allows for increased Rb+ conductance rates comparable to K+ conductance rates, an effect strictly correlating with a fast flicker block event in the channel.35 This effect is reduced when KV7.1 is coexpressed with KCNE1, and the fast flicker block is a major determinant of maximal conduction through the channel complex.35 We utilized the Rb+/K+ effects to assess whether the mutation A287T may affect the fast flicker block and its modulation by KCNE1. When exchanging extracellular K+ by Rb+, the inward currents through the KV7.1 pore were increased by a factor of about 2 in WT but only by approximately 1.5 in KV7.1-A287T. On the contrary, Rb+ inward currents compared with K+ inward currents were slightly reduced in KV7.1-WT/KCNE1 and remained unaffected in KV7.1-A287T/KCNE1. Therefore, both A287T mutations of homomeric KV7.1 and heteromeric KV7.1/KCNE1 channels results in reduced Rb+ vs K+ selectivity. However, the degree of KCNE1 modulation in A287T is reduced.

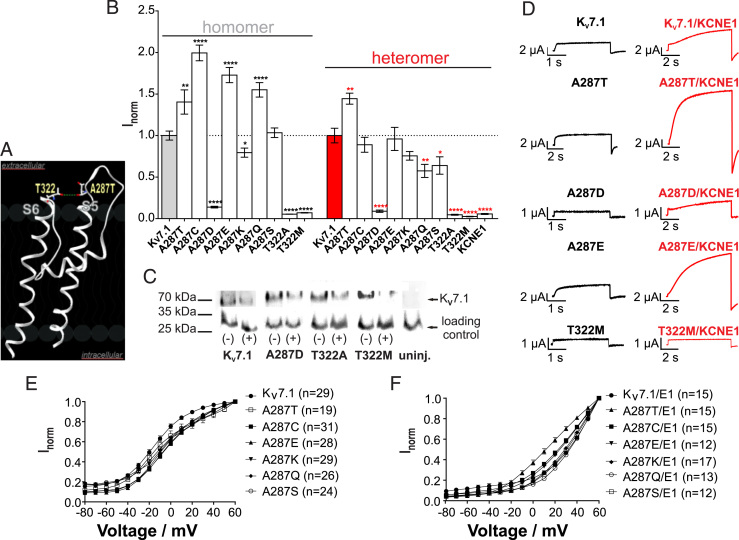

The amino acid position A287 is a structurally relevant key amino acid

To better understand these findings, we generated an in silico homology model of the KV7.1 transmembrane domain (Figure 3). The residue A287 was localized at a position that allowed the formation of a hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl group of T322 and the backbone of A287. This hydrogen bond potentially stabilizes the outer pore domain within one KV7.1 subunit (Figure 3A). To analyze this possible interaction, we replaced the alanine at position 287 with threonine, cysteine, asparagine, lysine, glutamine, or serine and assessed the function of the resulting mutants by TEVC experiments. Furthermore, we exchanged threonine 322 with alanine and methionine. Several mutant channels at residue 287 (A287T/C/E/K/Q/S) exhibited typical gain-of-function effects as compared with WT channels (Figure 3B). In contrast, mutants T322A, T322M, and also A287D expressed in oocytes exhibited largely reduced ion currents (Figure 3B) and thus were consistent with a reduced repolarization force. Of note, T322M has been linked to LQT136 and we had also identified this mutation in a small family with typical LQTS (4.1E). To address whether these differences were due to altered protein expression, we performed Western blot experiments using oocytes expressing the different mutant channels. We observed similar expression levels of the mutated KV7.1 proteins as compared with KV7.1-WT, which rules out that the impaired protein function is due to reduced expression levels (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Analysis of homomeric and heteromeric KV7.1-WT and mutant channels (molar ratio 6:1) do not exert a clear correlation of functional effects with simple chemical side chain features. A: Three-dimensional model of segment S5 and S6 of KV7.1 channel suggesting an interaction of KV7.1-A287 with KV7.1-T322. B: Normalized current amplitudes of KV7.1-A287 and KV7.1-T322 compared with KV7.1-WT in absence or presence of KCNE1. Change in current measured at the end of a 7-second pulse to +40 mV (n = 10–34, ± standard error of the mean, unpaired t test, ****P < .0001). C: Representative Western blot depicting KV7.1 surface membrane expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes in absence (-) and presence (+) of KCNE1. D: Representative current trace of +40 mV pulse in absence or presence of KCNE1. Currents were elicited with 7-second pulses to potentials of -100 to +60 mV in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of -80 mV. E, F: Activation curves of KV7.1-WT and mutant KV7.1 (A287T) in absence or presence of KCNE1. Curves were obtained by normalization of initial tail currents to the respective value at +60 mV.

Next, we sought to identify molecular properties of residue 287 by analyzing the effects of charge, volume, and hydrophobicity at this position on channel function. However, we did not observe a correlation of current amplitudes with any of these features (Supplementary Figure S1, available online). The voltage dependence of activation V1/2 was shifted to depolarized potentials by all mutants except A287T, whereas slope (k) was altered by all mutations (Supplementary Figure S2, available online). When coexpressed with KCNE1, only mutant KV7.1-A287T showed a clear shift of the voltage dependence of channel activation toward more hyperpolarized potentials. However, owing to the nonsaturating character of KV7.1/KCNE1 channel currents no clean Boltzmann fit was possible.

Molecular simulation suggests that side chain at position 287 is a key residue for KV7.1–KCNE1 interaction

Lastly, we performed molecular dynamics simulations (Supplementary Figure S3, available online) using a recently published model of the KV7.1/KCNE1 complex.28 A287T was inserted into the model and energy minimization was performed on both mutant and WT models. Molecular modeling simulations were then carried out on both models in parallel. The channels were incorporated into membranes and simulated in 0.9% NaCl for 10 nanoseconds, with all atoms being mobile. Both models reached stable conformations within this time frame, as indicated by an acquired steady state (root mean square deviation value approaching plateau, Supplementary Figure S3D). In average structures overlaid in Supplementary Figure S3A, we observed that the selectivity filter was slightly rearranged in the KV7.1-A287T model. Furthermore, the outer domain of both KCNE1 subunits (colored in red) was largely repositioned, whereas those of WT-channel complexes stayed in position (yellow). Magnification of the area of interest (Supplementary Figure S3B) shows a stable interaction between A287 and T322 of the same KV7.1 subunit and with Q23 of the adjacent KCNE1 β-subunit. On the contrary, KV7.1-A287T causes some local rearrangements that affect the outer KCNE1 structure (Supplementary Figure S3 and Supplementary Table S1, available online). Although KV7.1-A287 still interacts with KV7.1-T322 and KCNE1-Q23, additional stable interactions with KV7.1-Q323 and KCNE1-G40 could be observed in silico (Supplementary Figure S3C). The rearrangement of the outer KCNE1 induced changes in the dynamics of the channel complex. In KCNE1 we detected changes in a measure of conformational freedom of a residue (root mean square fluctuations, RMSF) in the outer domain but not in the transmembrane segment (Supplementary Figure S3E). Furthermore, differences in RMSF of residues in the S3–S4 linker, the outer S5–pore helix linker, and the outer vestibule close to the selectivity filter could be observed (Supplementary Figure S3F). In addition, the outer domain structure in the region of residues 23–40 was markedly changed in both KCNE1 subunits of the KV7.1-A287T/KCNE1 channel complex (Supplementary Figure S3E). The RMSF of KV7.1-A287T itself was reduced within both KV7.1-KCNE1 interaction regions compared with the simulation in the same subunit. This reduction may result from strengthened backbone interactions with KV7.1-T322 (by the proposed H-bond), as indicated by the reduced RMSD in the backbones (Supplementary Table S2, available online). In sum, these simulations show that (1) residue KV7.1-A287 is forming a stable H-bond to allow for a correct selectivity filter structure and that (2) interaction with KCNE1-Q23 allows for correct KCNE1-KV7.1 interaction in silico. Thus, KV7.1-A287 is a key residue both for normal KV7.1 selectivity structure and normal KCNE1 interaction. This is impaired in disease-associated KV7.1-A287T/KCNE1 channels based on in silico simulations.

Discussion

Our clinical investigation indicates that the patient carrying KV7.1-A287T is presented with a prominent SQT2, implying an accelerated ventricular repolarization. This is consistent with other SQT2 mutations, which all cause a gain-of-function phenotype in heterologous expression systems.37 We thoroughly characterize KV7.1-A287, which associates in the short repolarization disorder (SQT2). Our data indicate a shift of the voltage-dependent activation of IKS channels toward hyperpolarization, meaning that more channels activate faster and generate a higher macroscopic current amplitude (Figure 2A and B). Thus, the characterized mutation A287T elicited a classic gain of function involving increased voltage dependence.

We show that the alanine residue at position 287 in KCNQ1 is crucial for normal channel function. Possibly, the gain-of-function phenotype could be a result of altered conductance through the selectivity filter substantiated by localization of A287 in the S5 segment of KV7.1 near the pore. Our results show that the conductance ratio of Rb+/K+ is smaller in KV7.1-A287T compared with WT channels and KV7.1 conducts Rb+ much better than K+, an effect that is inversed upon KCNE1 coassembly.35, 38, 39 The clear inversion by coexpression with KCNE1 is much milder in the mutant channel complex. This shows that the KCNE1 effects on fast flicker block, a well-known KCNE1 effect on the selectivity filter, are reduced in KV7.1-A287T mutant channels (Figure 2C–E). Thus, the influence of rate-limiting fast flicker block in Kv7.1/KCNE1 channels may be reduced in A287T channels, additionally contributing to the gain-of-function phenotype beside increased channel availability owing to increased voltage dependence.

Our data substantiate the crucial role of alanine at position 287 for physiological channel function. We performed a wide-range amino acid substitution at position A287 and T322 in KCNQ1. Substitutions of amino acids at this location caused gain-of-function or loss-of-function phenotypes (Figure 3). Our systematic mutational analysis indicates that alanine, with its short neutral side chain, is key for channel function in that amino acid substitutions in this position are not well tolerated. This finding is in agreement with the 3-dimensional model, in which the methyl group interacts with KCNE1 to allow for precise KV7.1/KCNE1 arrangement. Interestingly, there is no clear correlation between gain/loss of function and biochemical features due to amino acid exchange at KV7.1-287 (charge, volume, or hydrophobicity; Supplementary Figure 2A–F).

Based on homology modeling, KV7.1-A287 (backbone) is predicted to form an H-bond with T322 (Figure 3A). Mutations KV7.1-T322A and KV7.1-T322M cause a severe loss of function, as shown here (Figure 3), and were reported to be associated with LQT1.36, 40, 41 Both mutations can be expected to disrupt the H-bond because the H-donor in the threonine side chain is eliminated by the mutation. Interestingly, both KV7.1-T322M and KV7.1-T322A do reach the plasma membrane and thus, the H-bond may rather be important for intrinsic protein function (Figure 3C). This interaction may be important to stabilizing the arrangement of S5, S6, and the central pore domain/selectivity filter. Indeed, this arrangement was reported to affect the selectivity filter, conductance, and ion selectivity.42 Elimination of the proposed H-bond between KV7.1-A287 with KV7.1-T322 by LQT1 mutations KV7.1-T322A or KV7.1-T322M gives rise to nonfunctional channels that are plasma membrane associated. The lack of function of these channels must therefore result from mutational effects that are intrinsic to the channel protein structure rather than from trafficking defects (Figure 3B–D). The simple distance analysis suggests that the KV7.1-A287 residue interacts with the KCNE1-Q23 residue in silico as well (Supplementary Figure S3). Van der Waals interaction may stabilize the KV7.1-KCNE1 subunit arrangement at this site in the outer region. Mutant KV7.1 subunits (A287T) would change these local interactions, thereby structurally increasing rigidity at KV7.1-A287T (Supplementary Table 2). Further, structural motifs in the outer KCNE1 domain (Supplementary Figure S3) are impaired, as suggested by our molecular dynamics simulations. The simulations were performed using a 3-dimensional model28 that is based on modeling and cys-crosslinking experiments in the region under investigation in this present study. Thus, according to our in silico predictions, the triad of KV7.1-T322, KV7.1-A287, and KCNE1-Q23 is expected to be crucially important for KV7.1/KCNE1 channel complex function.

This predicted functional triad is compromised by mutation KV7.1-A287 to cause:

-

–

Extensive functional effects depending on the specific amino acid present at position 287;

-

–

Atypical influences of KCNE1 on ion channel conductance;

-

–

Modified KV7.1 ion selectivity. A287 mutations influence the structural arrangement of S5, S6, and the central pore domain/selectivity filter, which is of high relevance to ion selectivity and conductance.42

Conclusion

We have identified a structural triad formed by two distinct residues in KV7.1 (T322 and A287, respectively) and one residue in KCNE1 (Q23) that is essential for regular KV7.1-KCNE1 subunit interaction. Structural disturbances at these residues, for example by human LQT gene mutations, exhibit opposite effects of IKs channel function and may result in either a gain-of-function or a loss-of-function phenotype with clinically shortened (SQT) or prolonged (LQT) repolarization. These patients may suffer not only from fatal ventricular arrhythmias, but also at times from atrial arrhythmias.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gea Ny Tseng for helpful comments on the manuscript and provision of the KV7.1/KCNE1 3-dimensional models.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.hrcr.2016.08.015.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Marx S.O., Kurokawa J., Reiken S., Motoike H., D׳Armiento J., Marks A.R., Kass R.S. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science. 2002;295:496–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1066843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanguinetti M.C., Jurkiewicz N.K., Scott A., Siegl P.K. Isoproterenol antagonizes prolongation of refractory period by the class III antiarrhythmic agent E-4031 in guinea pig myocytes. Mechanism of action. Circ Res. 1991;68:77–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh K.B., Kass R.S. Regulation of a heart potassium channel by protein kinase A and C. Science. 1988;242:67–69. doi: 10.1126/science.2845575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Embark H.M., Bohmer C., Vallon V., Luft F., Lang F. Regulation of KCNE1-dependent K(+) current by the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) isoforms. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445:601–606. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0982-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang F., Henke G., Embark H.M., Waldegger S., Palmada M., Böhmer C., Vallon V. Regulation of channels by the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase - implications for transport, excitability and cell proliferation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2003;13:41–50. doi: 10.1159/000070248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seebohm G., Strutz-Seebohm N., Birkin R. Regulation of endocytic recycling of KCNQ1/KCNE1 potassium channels. Circ Res. 2007;100:686–692. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260250.83824.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanguinetti M.C., Jurkiewicz N.K. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Gen Physiol. 1990;96:195–215. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odening K.E., Hyder O., Chaves L., Schofield L., Brunner M., Kirk M., Zehender M., Peng X., Koren G. Pharmacogenomics of anesthetic drugs in transgenic LQT1 and LQT2 rabbits reveal genotype-specific differential effects on cardiac repolarization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2264–2272. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00680.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wessely R., Klingel K., Santana L.F., Dalton N., Hongo M., Jonathan Lederer W., Kandolf R., Knowlton K.U. Transgenic expression of replication-restricted enteroviral genomes in heart muscle induces defective excitation-contraction coupling and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1444–1453. doi: 10.1172/JCI1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerlach U. Blockers of the slowly delayed rectifier potassium IKs channel: potential antiarrhythmic agents. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2003;1:243–252. doi: 10.2174/1568016033477469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedley P.L., Jørgensen P., Schlamowitz S., Wangari R., Moolman-Smook J., Brink P.A., Kanters J.K., Corfield V.A., Christiansen M. The genetic basis of long QT and short QT syndromes: a mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1486–1511. doi: 10.1002/humu.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulze-Bahr E., Wang Q., Wedekind H. KCNE1 mutations cause jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:267–268. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seebohm G., Chen J., Strutz N., Culberson C., Lerche C., Sanguinetti M.C. Molecular determinants of KCNQ1 channel block by a benzodiazepine. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:70–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinke K., Sachse F., Ettischer N. Coxsackievirus B3 modulates cardiac ion channels. FASEB J. 2013;27:4108–4121. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-230193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q., Curran M.E., Splawski I. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitt N., Schwarz M., Peretz A., Abitbol I., Attali B., Pongs O. A recessive C-terminal Jervell and Lange-Nielsen mutation of the KCNQ1 channel impairs subunit assembly. EMBO J. 2000;19:332–340. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwake M., Jentsch T.J., Friedrich T. A carboxy-terminal domain determines the subunit specificity of KCNQ K+ channel assembly. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:76–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamgar L., Ma L., Schmitt N., Haitin Y., Peretz A., Wiener R., Hirsch J., Pongs O., Attali B. Calmodulin is essential for cardiac IKS channel gating and assembly: impaired function in long-QT mutations. Circ Res. 2006;98:1055–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218979.40770.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt N., Grunnet M., Olesen S.P. Cardiac potassium channel subtypes: new roles in repolarization and arrhythmia. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:609–653. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo S.H., Teo W.S., Ching C.K., Chan S.H., Lee E.J. Mutation screening in KCNQ1, HERG, KCNE1, KCNE2 and SCN5A genes in a long QT syndrome family. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:394–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell C.M., Campbell J.D., Thompson C.H., Galimberti E.S., Darbar D., Vanoye C.G., George A.L., Jr Selective targeting of gain-of-function KCNQ1 mutations predisposing to atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:960–966. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steffensen A.B., Refsgaard L., Andersen M.N., Vallet C., Mujezinovic A., Haunsø S., Svendsen J.H., Olesen S.P., Olesen M.S., Schmitt N.I. Gain- and loss-of-function in early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015 Jul;7:715–723. doi: 10.1111/jce.12666. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jce.12666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olesen M.S., Bentzen B.H., Nielsen J.B., Steffensen A.B., David J.P., Jabbari J., Jensen H.K., Haunsø S., Svendsen J.H., Schmitt N. Mutations in the potassium channel subunit KCNE1 are associated with early-onset familial atrial fibrillation. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundby A., Ravn L.S., Svendsen J.H., Olesen S.P., Schmitt N. KCNQ1 mutation Q147R is associated with atrial fibrillation and prolonged QT interval. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1532–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckey K., Wrobel E., Strutz-Seebohm N., Pott L., Schmitt N., Seebohm G. Novel Kv7.1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate interaction sites uncovered by charge neutralization scanning. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22749–22758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.589796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang C., Tian C., Sönnichsen F.D., Smith J.A., Meiler J., George A.L., Jr, Vanoye C.G., Kim H.J., Sanders C.R. Structure of KCNE1 and implications for how it modulates the KCNQ1 potassium channel. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7999–8006. doi: 10.1021/bi800875q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian C., Vanoye C.G., Kang C., Welch R.C., Kim H.J., George A.L., Jr, Sanders C.R. Preparation, functional characterization, and NMR studies of human KCNE1, a voltage-gated potassium channel accessory subunit associated with deafness and long QT syndrome. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11459–11472. doi: 10.1021/bi700705j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y., Wang Y., Meng X.Y., Zhang M., Jiang M., Cui M., Tseng G.N. Building KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel models and probing their interactions by molecular-dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2013;105:2461–2473. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wemhöner K., Friedrich C., Stallmeyer B., Coffey A.J., Grace A., Zumhagen S., Seebohm G., Ortiz-Bonnin B., Rinné S., Sachse F.B., Schulze-Bahr E., Decher N. Gain-of-function mutations in the calcium channel CACNA1C (Cav1.2) cause non-syndromic long-QT but not Timothy syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;80:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bazett H.C. An analysis of the time-relations of electrocardiograms. Heart. 1920;7:353–370. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fridericia L.S. Die Systolendauer im Elektrokardiogramm bei normalen Menschen und bei Herzkranken. Acta Med Scand. 1920;53:469–486. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jespersen T., Grunnet M., Angelo K., Klaerke D.A., Olesen S.P. Dual-function vector for protein expression in both mammalian cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biotechniques. 2002;32:536–538. doi: 10.2144/02323st05. 540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strutz-Seebohm N., Pusch M., Wolf S., Stoll R., Tapken D., Gerwert K., Attali B., Seebohm G. Structural basis of slow activation gating in the cardiac I Ks channel complex. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27:443–452. doi: 10.1159/000329965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Priori S.G., Wilde A.A., Horie M. Executive summary: HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Europace. 2013;15:1389–1406. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seebohm G., Sanguinetti M.C., Pusch M. Tight coupling of rubidium conductance and inactivation in human KCNQ1 potassium channels. J Physiol. 2003;552:369–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Priori S.G., Napolitano C., Schwartz P.J., Grillo M., Bloise R., Ronchetti E., Moncalvo C., Tulipani C., Veia A., Bottelli G., Nastoli J. Genetic testing in the long QT syndrome: development and validation of an efficient approach to genotyping in clinical practice. JAMA. 2005;294:2975–2980. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H., Kharche S., Holden A.V., Hancox J.C. Repolarisation and vulnerability to re-entry in the human heart with short QT syndrome arising from KCNQ1 mutation--a simulation study. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:112–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pusch M., Bertorello L., Conti F. Gating and flickery block differentially affected by rubidium in homomeric KCNQ1 and heteromeric KCNQ1/KCNE1 potassium channels. Biophys J. 2000;78:211–226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76586-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2001.

- 40.Choi G., Kopplin L.J., Tester D.J., Will M.L., Haglund C.M., Ackerman M.J. Spectrum and frequency of cardiac channel defects in swimming-triggered arrhythmia syndromes. Circulation. 2004;110:2119–2124. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144471.98080.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang S., Yin K., Ren X., Wang P., Zhang S., Cheng L., Yang J., Liu J.Y., Liu M., Wang Q.K. Identification of a novel KCNQ1 mutation associated with both Jervell and Lange-Nielsen and Romano-Ward forms of long QT syndrome in a Chinese family. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seebohm G., Westenskow P., Lang F., Sanguinetti M.C. Mutation of colocalized residues of the pore helix and transmembrane segments S5 and S6 disrupt deactivation and modify inactivation of KCNQ1 K+ channels. J Physiol. 2005;563:359–368. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material