Abstract

Children in foster care have high rates of adverse childhood experiences and are at risk for mental health problems. These problems can be difficult to ameliorate, creating a need for rigorous intervention research. Previous research suggests that intervening with children in foster care can be challenging for several reasons, including the severity and complexity of their mental health problems, and challenges engaging this often transitory population in mental health services. The goal of this article was to systematically review the intervention research that has been conducted with children in foster care, and to identify future research directions. This review was conducted on mental health interventions for children, ages 0 to 12, in foster care, using ERIC, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed, ProQuest’s Dissertation and Theses Database, Social Services Abstracts, and Social Work Abstracts. It was restricted to interventions that are at least “possibly efficacious” (i.e., supported by evidence from at least one randomized controlled trial). Studies were evaluated for risk of bias. Ten interventions were identified, with diverse outcomes, including mental health and physiological. Six interventions were developed for children in foster care. Interventions not developed for children in foster care were typically adapted to the foster context. Most interventions have yet to be rigorously evaluated in community-based settings with children in foster care. Little research has been conducted on child and family engagement within these interventions, and there is a need for more research on moderators of intervention outcomes and subgroups that benefit most from these interventions. In addition, there is not consensus regarding how to adapt interventions to this population. Future research should focus on developing and testing more interventions with this population, rigorously evaluating their effectiveness in community-based settings, determining necessary adaptations, and identifying which interventions work best for whom.

Keywords: Foster care, interventions, treatment, systematic review, child maltreatment, engagement

Approximately 400,000 children in the US are in foster care each year (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2014), and costs associated with foster care near $30,000 per child, per year in some states (New York State Office of Children and Family Services, 2010). “Foster care” is used as an umbrella term in this paper, to refer simultaneously to traditional foster placements, relative and/or kinship care placements, group homes, and residential settings. Children are typically placed in foster care due to child abuse and neglect, and 70% of former foster children report over five adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Bruskas & Tessin, 2013). Other than child abuse and neglect, ACEs for children in foster care include exposure to community violence (Garrido, Culhane, Raviv, & Taussig, 2010) and to domestic violence (Stein et al., 2001), transitions in primary caregivers that disrupt attachment relationships (Stovall McClough & Dozier, 2004), and in-utero exposure to drugs and alcohol (Smith, Johnson, Pears, Fisher, & DeGarmo, 2007).

Due to the risk factors experienced by children in foster care and their subsequent consequences, these children exhibit great mental health need. Between 50 and 80% of children in foster care meet criteria for a mental health disorder (Farmer et al., 2001; Leslie et al., 2005). Twenty-three percent meet criteria for more than one mental health disorder (Garland, Hough, McCabe, Yeh, Wood, & Aarons, 2001). Common mental health diagnoses among children in foster care include disruptive behavior disorders and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (54%, Garland et al., 2001), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (20%; Kolko, Hurlburt, Zhang, Barth, Leslie, & Burns, 2010), other anxiety disorders (10%; Garland et al., 2001), and mood disorders (7%, Garland et al., 2001). There is also a high rate of developmental concerns, such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (~6%, Lange, Shield, Rehm, & Popova, 2013) and cognitive impairments (~25%; Casanueva et al., 2011). Given these high rates of social-emotional and developmental problems, children in foster care typically exhibit poor functioning throughout their lives, struggling with unemployment, incarceration, substance dependence, and early childbearing (Courtney et al., 2011).

Amidst the need for mental health intervention, however, is the reality that many children in foster care who receive mental health services do not get better (Bellamy, Gopalan, & Traube, 2010; McCrae, Barth, & Guo 2010). McCrae and colleagues used a nationally representative sample of children in foster care from the NSCAW database to compare behavioral and emotional symptoms of children who had received mental health services and children who had not. Using a propensity score matching design, they found that in the overall sample, behavioral and emotional problems decreased over time, but that in the sample of children who received mental health services, behavioral and emotional problems increased over time. Bellamy and colleagues (2010) had similar findings. They also used NSCAW data and a propensity score matching design. Results indicated that children who had been in “long term” foster care (or in care for at least a year) did not benefit from outpatient mental health “services as usual.” Both articles concluded that it is extremely difficult to successfully treat children in foster care. Thus, they urged further intervention research to help inform best practices for intervention.

Beyond the severity and complexity of mental health and comorbid concerns, there are other challenges in treating children in foster care. First, children live in diverse and in many times transitory settings, spanning from traditional foster homes to group-care settings. Thus, some interventions, such as those originally developed for parent-child dyads, may not feel like a good fit to children and their families due to different relationship dynamics (Taussig & Raviv, 2014), or may not be plausible given a child’s current living situation (e.g. frequent transitions between settings). Second, data from a repository of US State Child Welfare Data indicate that of school-aged youth who entered foster care in 2005–2009, nearly 60% had experienced two or more placements by the end of 2011, including 10% who had experienced six or more placements (National Working Group on Foster Care and Education, 2014). Placement changes occur even more frequently for children with significant behavioral problems (James, Landsverk, Slymen, & Leslie, 2004), and make continuity of mental health services tenuous. Third, foster caregivers are often over-burdened with caring for multiple children in foster care, and thus it can be difficult for them to find time to engage in treatment or to transport children to treatment (Dorsey, Conover, & Cox, 2014). Finally, many foster families, particularly relatives of the child, may prefer to avoid the perceived stigma associated with engaging in mental health services (Kools, 1997). Two-thirds of children and families who are enrolled in outpatient mental health services do not complete more than seven sessions (Miller, Southam-Gerow, & Allin, 2008), and for children in foster care, this rate is likely to be much higher (see Burns et al., 2004; Dorsey, et al., 2014; Taussig & Raviv, 2014 for further discussion on engagement in this population).

A previous review of interventions for children in foster care (Leve et al., 2012), aimed at summarizing interventions specifically developed to address mental health and developmental concerns for children and adolescents in foster care, identified eight interventions. It focused on interventions supported by data from at least one randomized controlled trial (RCT; i.e., at least possibly efficacious, Chambless & Hollon, 1998). A major conclusion from this review was that many mental health problems experienced by children in foster care can be ameliorated with the use of targeted, research-informed and supported approaches. Another conclusion, however, was that increased efforts to understand how to best use these programs in real-world settings was necessary.

The current review extends findings from the previous review in a few ways. Similar to Leve and colleagues (2012), we only review interventions that are at least possibly efficacious (i.e., supported by findings from at least one RCT). However, in contrast to Leve and colleagues (2012), some of the possibly efficacious interventions that we review were not specifically developed for children in foster care, yet have been evaluated with children in foster care, although sometimes via less rigorous designs (e.g., pre-post pilot trials). This wider net of inclusion in our review is important. Generalizing interventions to the foster context is likely to require additional research, and we wanted to recognize interventions with preliminary work in this area. Second, this review reports what is known about child and family engagement (defined as enrollment rates and attendance) in these interventions, and the research on moderators or subgroups has been conducted. Engagement is often a prerequisite to attaining mental health benefits from services (Chu & Kendall, 2004). Because of the many barriers to foster children and families’ engagement in mental health services, it is important to know how well interventions are engaging foster families (Dorsey et al., 2014; Taussig & Raviv, 2014). Third, the current review diverges from the former review in that it highlights the status of the empirical support for each intervention within the foster population (e.g., controlled efficacy trial, controlled effectiveness trial, etc.), which can help identify what research is needed to delineate a specific intervention’s utility with this population. Finally, the current review is limited to children ages 0 to 12. Age was restricted in our review due to the breadth of the interventions reviewed.

The focus of this paper is on interventions that can be delivered in outpatient settings. This focus, at times, naturalistically excludes children living in group homes or residential settings. We are aware of at least one intervention, however, that we reviewed that served some children who were living in residential or group care settings (Taussig & Culhane, 2010). As such, the results presented here are limited by service delivery site, not placement type, but are heavily weighted toward children living in traditional foster or relative and/or kinship placements. We chose to focus on the outpatient setting because outpatient settings serve a broad range of children, and because it is important to understand how to treat children in foster care within this context to help reduce reliance on residential settings.

The specific questions guiding this review were: (1) Which “possibly efficacious” interventions have been evaluated with foster populations in outpatient settings, and what are their characteristics? (2) What is the status of the empirical support for these interventions? (3) What are the outcomes, and what subgroup/moderator analyses of outcomes have been conducted? And, (4) What are the enrollment, retention, and attendance rates for these interventions? A narrative systematic review of the literature was employed to answer these questions.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

Methods outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (PRISMA; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) were followed. A full review protocol is available from the corresponding author. Authors searched for peer-reviewed empirical studies of possibly efficacious interventions delivered to 0- to 12-year-old children in foster care. Additional inclusion criteria included: (1) Intervention evidenced at least one positive child mental health outcome for children in foster care; (2) Intervention could be delivered in-home or in outpatient/community settings; (3) Intervention was not solely enhanced foster care or wraparound services (as defined by having at least one specific therapeutic component unique to the intervention); (4) Outcomes or engagement rates were measured post-intervention, (5) Article reported on an evaluation of an intervention’s efficacy or effectiveness (e.g., it was not a program evaluation); (6) Intervention could be delivered in English.

Search Strategy

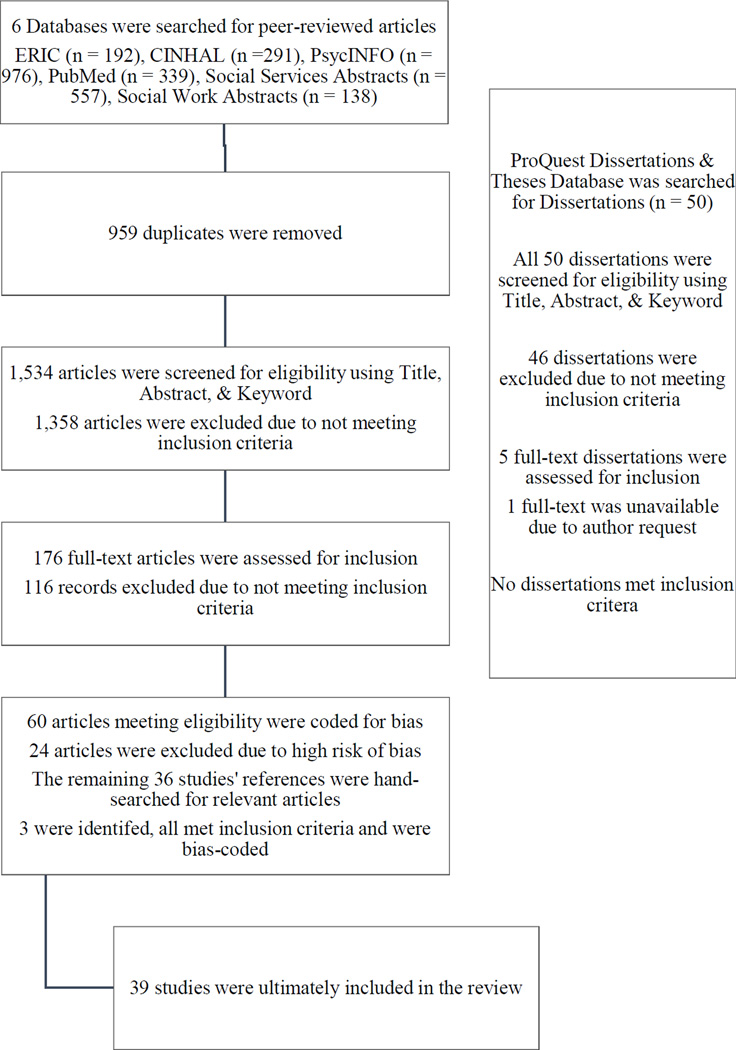

ERIC, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed, Social Services Abstracts, and Social Work Abstracts were selected as search engines for peer-reviewed articles. ProQuest’s Dissertation and Theses Database was selected as the search engine for non-peer reviewed articles, to help guard against publication bias while maintaining a systematic search strategy (for similar search methods to address publication bias, see Weisz et al., 2013). Search terms were selected through consultation with University library staff to ensure that our search was broad enough to return the vast majority of relevant articles. Search terms were also shared with foster care researchers from several countries so that the authors could receive feedback regarding whether the terms were broad enough to capture research occurring in countries outside of the USA. The following search terms were entered into all search engines: (“foster care” OR “kin care” OR “relative care” OR “out-of-home care”) AND (intervention OR treatment OR therapy OR training OR program) AND (children OR kids OR infants OR preschoolers OR toddlers). In PsycINFO, Title, Abstract, and Keyword were the search fields. In PubMed Title/Abstract was the search field. In ERIC, CINAHL, Social Services Abstracts, and Social Work Abstracts, Abstract was the search field. In the six aforementioned search engines, the review was restricted to empirical, peer-reviewed articles published since 1990. For the Dissertation and Theses Database, Keyword was the search field for the foster care and intervention-related terms, and Abstract for the child-related terms. This search was also restricted to dissertations completed since 1990. Searches were restricted to research conducted since 1990 in an effort to review interventions currently available to mental health providers and to expedite dissemination of findings (e.g., Ganann, Ciliska, & Thomas, 2010). Figure 1 shows the number of articles retrieved from each search engine, and the path by which articles ultimately came to be included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Process of Identifying Articles for Inclusion

Study Selection

A team of three coders participated in the study selection process. All coders had a PhD in psychology and had expertise in both clinical child psychology and child abuse and neglect. First, two coders read the title, abstract, and keywords of each article/dissertation returned by the initial searches. One coder was part of both teams, and so reviewed each and every article/dissertation. Articles were excluded if it was determined that they did not meet inclusion criteria (see the Flow Diagram in Figure 1 for the exact numbers of articles/dissertations included/excluded at each step). When coders did not agree if a study met criteria, input from the third coder was sought. Following consensus from all three coders, a determination of eligibility was made (the study had to meet all 6 of the aforementioned inclusion criteria). Next, two coders read the full text of each of the remaining articles (N = 176) and dissertations (N = 6) to determine if, after a full reading of the article/dissertation, they still met all 6 inclusion criteria. Studies meeting criteria were assessed for risk of bias at the study level (N = 60 articles, no dissertations met criteria). Risk of bias was defined as potential for systematic error based on study design and analyses, and was assessed using a coding scheme adapted from Goldman Fraser and colleagues (2013), who conducted a Comparative Effectiveness Review of interventions addressing child maltreatment for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The questions used to assess for bias are located in Table 1. Two coders assessed each article for bias and indicated whether the answer to each question was Yes, No, or Uncertain. Following coding, studies were excluded if (1) 50% of the answers to the set of questions indicated some risk of bias, (2) There had never been an RCT conducted with this intervention (the RCT could have been conducted in a non-foster sample), or (3) If the only RCT conducted with this intervention contained less than 10 children in each group. Following these search and coding procedures, the authors referred to four seminal documents regarding foster care and child maltreatment interventions to ensure that relevant interventions reviewed by these articles were not overlooked: a Comparative Effectiveness Review of interventions addressing child maltreatment from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2013), a review of foster care interventions by Leve and colleagues (2012), a chapter on foster care interventions by Taussig & Raviv (2014), and a review of interventions used to treat child abuse and neglect by Shipman and Taussig (2009). No additional interventions met our inclusion criteria. In addition, the 36 articles that were included following bias-coding were hand-searched for references meeting our inclusion criteria. Three relevant articles were identified, and these are articles were also coded for bias and were ultimately included in this review.

Table 1.

Questions used to determine risk of bias

| 1. | Was the study design prospective? |

| 2. | Were groups recruited from the same source population? |

| 3. | Were identical inclusion and exclusion criteria used in both groups? |

| 4. | Did investigators use appropriate randomization methods (blinded, randomization after baseline interviews)? |

| 5. | Were groups similar at baseline? |

| 6. | Were multiple reporters or data sources used to assess outcomes? |

| 7. | Were outcome assessors unaware of which intervention the participants received (i.e., blinded?) |

| 8. | Were measures taken to ensure fidelity to the intervention protocol? |

| 9. | Do study authors report either attrition statistics or that all participants who started the study completed the study? |

| 10. | Was the overall attrition for the study ≤ 30%? |

| 11. | Was the differential attrition between groups ≤15%? |

| 12. | Did investigators use an intent-to-treat analysis? |

| 13. | Were baseline differences between groups taken into account in the statistical analysis? |

| 14. | Were all prespecified outcomes reported in the results? |

Note. Questions were rated Y (yes), N (no), U (uncertain), or NA (not applicable).

The remaining articles (N = 39) were categorized as efficacy trials, effectiveness trials, or other trials (e.g. pilot trials of adaptations). The process of categorization followed criteria established for distinguishing efficacy versus effectiveness trials published in a Technical Review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Goldman Fraser et al., 2006), including inclusion criteria, study setting, and use of intent-to-treat analysis. Results of this categorization are shown in Table 2 and in the Supplemental Material. Finally, two coders coded each article for information on client characteristics (Supplemental Material), intervention characteristics (Table 3), and outcomes (Table 4).

Table 2.

Status of Evidence for Interventions for Children in Foster Care

| Intervention |

Created for Foster Care |

Adapted for Foster Care |

Efficacy Trial in Foster Care |

Efficacy Trial in Other Population |

Effectiveness Trial in Foster Care |

Other Study in Foster Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up (ABC) |

* | * | ||||

| Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) | * | * | ||||

| Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF) | * | * | ||||

| Incredible Years (IY) | * | * | * | * | ||

| Keeping Foster Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP) |

* | * | * | |||

| Kids in Transition to School Program (KITS) |

* | * | ||||

| Parent-Child Interaction Therapy | * | * | * | * | ||

| Short Enhanced Cognitive- Behavioral Parent Training (CEBPT) |

* | * | ||||

| Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) |

* | * | * | |||

| Treatment Foster Care Oregon for Preschoolers (TFCO-P) |

* | * | * |

Table 3.

Intervention Characteristics

|

Delivery Setting |

Placement Type |

Framework |

Components (e.g., group, caregiver- child) |

Participants |

Enrollment Rates |

Attendance | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catchup (ABC) – Intervention | |||||||

| Home | Any non- congregate |

Attachment Physiological Self- regulation |

Parent Education Parent-child interaction (coached in- vivo) |

Children ages 0 to 2 yrs & foster carers |

88.6% foster & 99% bio- logical carers consented; consent required from both |

Not reported |

10 weekly sessions |

| Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) – Intervention | |||||||

| Mental health service delivery sites |

Any non- congregate |

Attachment Psychodynamic Developmental Social learning Cognitive behavioral |

Play therapy techniques to improve parent-child relationship Parent education |

Children ages 0 to 6 & foster carers |

Not reported | Not reported |

Approximately one year |

| Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF) – Preventive Intervention | |||||||

| Community | Any foster child |

Cognitive Behavioral Positive Youth Development |

Individual Mentoring Skills Groups |

Children ages 9 to 11 yrs, recently placed in foster care |

91% | Children completed an average of 25 of 30 group sessions & 26.7 of 30 mentoring visits |

30 weekly individual mentoring visits 30 weekly skills groups |

| Incredible Years (IY) Adaptations – Preventive Intervention | |||||||

| Varied, included: Mental health service delivery site Child welfare agency Classroom -like setting |

Varied, included: Non-kin & non- congregate Any non- congregate |

Varied, included: Behavioral parent management training (2006, 2011) Social emotional learning Cognitive behavioral therapy (2012) |

Varied, included: Parent Management Training Foster & biological carer collaborative parenting training Adaptation of IY Dina Program for Young Children Parenting group to promote children’s skills use |

Varied, included: Foster carers & biological parents with children 3 to 10 yrs old Foster carers and children 8 to 13 yrs old Children 5 to 8 yrs & foster carers |

Ranged from: 81% to 75% |

All carers completed 9 of 12 sessions offered |

Varied, included: 12 weekly sessions 12 2h child group sessions, 3 2h parent groups |

| Keeping Foster Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP) – Intervention | |||||||

| RCT: Community Varied across Adaptations: Mental health service delivery site Home |

Any non- congregate |

Behavior management parent training |

Group parent training Homework |

In RCT: Foster carer with child ages 5 to 12 yrs in their homes In adaptation: Foster carer with child ages 4 to 12 yrs in their homes |

In RCT: 62% In Adaptation: 83% |

In RCT: 75% of families attended at least 90% of sessions |

16 90-min weekly sessions |

| Kids in Transition to School (KITS) – Intervention | |||||||

| Community | Any non- congregate |

Cognitive Behavioral Social- emotional learning Behavioral parent management training |

School readiness group Caregiver group Homework |

Children entering Kindergarten & foster carers |

57% | Children attended 69 to 74% of playgroup sessions 57 to 72% of children attended at least 75% of sessions Carers received 61 to 73% of sessions 55 to 73% received at least 75% of sessions |

4 mo (2 mo prior to Kindergarten, 2 mo after) 24 child school readiness sessions, 12 caregiver workshops |

| Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) – Intervention | |||||||

| Mental health service delivery sites |

Varied across adaptations: Any non- congregate Non- relative |

Behavioral parent management training Social learning theory Attachment theory |

Non- adaptation: Individual caregiver sessions Caregiver- child sessions Homework Adaptation: Group caregiver sessions Telephone consultation Homework |

Children ages 2 to 8 yrs and foster carers |

Non- adaptation: 83% of kin & 80% of non-kin Adaptations: 83.05% 75% 82% |

Not reported |

Varied across adaptations: 14 hrs parent management training At least 4 weekly & 4 biweekly telephone consultations |

| Short Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Parent Training (CEBPT) – Intervention | |||||||

| Not specified |

Any non- congregate |

Cognitive Behavioral Caregiver emotion regulation |

Group parent training (cognitive behavioral & caregiver emotion regulation) Homework |

Foster carers who had children ages 5 to 18 yrs with externalizing problems in their homes |

86% | 79% of those allocated to intervention received all sessions |

4 weekly 4- hr sessions with 3-mo 4-hr follow- up session |

| Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) – Intervention | |||||||

| Mental health service delivery sites |

Any non- congregate |

Cognitive Behavioral Behavioral exposure therapy Family therapy |

Child sessions Caregiver sessions Conjoint (child + caregiver) sessions |

Children ages 6 to 15 yrs, M age = 8.4, and foster carers |

Foster RCT: 89% Foster Pre- post study: Not reported |

Foster RCT: 72.72% attended > 4 sessions (regular TF-CBT) 92% attended > 4 sessions (TF-CBT plus engagement intervention) |

12–16 weeks |

|

Treatment Foster Care Oregon for Preschoolers (TFCO-P) – Intervention & Preventive Intervention | |||||||

| Conducted across multiple settings, including: Home Mental health service delivery sites Preschools |

Any non- congregate |

Developmental Behavioral parent management training Social skills training Cognitive behavioral |

Foster caregiver individual & group training Individual foster caregiver consultation & support Child individual therapy Child group therapy Psychiatric or specialist consultation as needed Individual parent management training for permanent placement |

Children ages 3 to 6 yrs beginning new foster placement & foster carers |

89% | Not reported |

6 to 9 months, from new placement entry to transition to permanent placement |

Note. Data obtained from the published articles (cited in Supplemental Material) and intervention overview articles (cited in References). Unless noted, data are from studies with foster populations. RCT = randomized controlled trial. Enrollment rates reflect enrollment in research studies; may not reflect those who began interventions.

Table 4.

Interventions for children in foster care: What works for whom?

|

Post- traumatic Stress |

Behavior | Internalizing | Attachment | Physiological | Placement |

Cognitive or Academic |

Caregiver |

Quality of Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) | ||||||||

| Decreased behavior problems for toddlers, not infants (2006) |

Decreased avoidance behaviors (2000) (2009) Decreased disorganized attachment, d = .52, (2012) Increased secure attachment, d = .38, (2012) |

Cortisol improvements (2006) Cortisol improvements, β = - .27, (2008) |

Improved cognitive flexibility, d = 1.06, (2012) Improved Theory of Mind, d = 1.08 (2012) |

Improved carer sensitivity to infants, β = .09, (2013) |

||||

| Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) | ||||||||

| Decreased posttraumatic stress for Hispanic, Black, & Biracial children (2009) |

Improved behavioral functioning for Black, Hispanic & Biracial children (2009) Improved risk behaviors for African American and Biracial children (2009) |

Improved emotional functioning for Black, Hispanic & Biracial children (2009) |

Improved child strengths for Black & Biracial children (2009) Improved life domain functioning for Black, Hispanic & White children (2009) |

|||||

| Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF) | ||||||||

| Decreased dissociative symptoms, d = .39, (2010) |

Decreased composite internalizing problems, d = −.51, (2010) |

Non- relative placements had: less placement changes (OR = .56), less residential placements (OR = .18), more permanentcy (OR = 5.14) (2012) |

||||||

| Incredible Years (IY) | ||||||||

| Decreased physical aggression for boys (2012) Decreased intensity of behavior problems; between ~ 23 & 30% of children with “ clinically significant” problems at baseline were no longer significant at f/u (2011) |

Foster carers increased use of positive discipline at intervention end (d = .40) and 3- mo f/u (d = .59) & clear expectations at 3-mo f/u (d = .54) (2006) Improved co- parenting between biological & foster carers at intervention end (d ranged from .42- .52) (2006) |

|||||||

| Keeping Foster Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP) | ||||||||

| Decreased behavior problems, d = .26 (2008a) Decreased behavior problems, β = −4.77, (2011) |

Decreased internalizing problems, β = −5.95, (2011) |

Increased positive exits from care (e.g., adoption, reunification), exp(β) = 1.96, (2008b) |

Increased foster carer use of positive reinforcement, d = .29 (2008a) |

|||||

| Kids in Transition to School (KITS) | ||||||||

| Decreased oppositional and aggressive behaviors d = .33 (2012) Increased behavioral self- regulation, ES = .18 (2013) |

Increased emotional self- regulation, ES = .18, (2013) |

Improved early literacy skills, ES = .26, (2013) |

||||||

| Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) | ||||||||

| Decreased externalizing problems, η2 = .27, (2006) Decreased internalizing, externalizing and total problems, η2 = .13, (2006) Decreases in overall severity of concerns, η2 = .13, (2006) Decreased externalizing problem intensity, (both PCIT adaptation groups; combined R2 = .04) (2014) Decreased externalizing problem severity (both PCIT adaptations; combined R2 = .06 & .09 for both problem severity measures ) (2014) |

Decreased internalizing problems, combined R2 = .08, (both PCIT adaptation groups; 2014) |

Decresead foster carer parental distress, η2 = .05, (2006) Decreased foster carer child abuse potential, η2 = .04, (2006) Decreased foster carer total stress, both PCIT adaptations, d = .45, (2015)* Decreased foster carer child- related parenting stress, η2 = .15 (2006), d =.47−.50, (2015)* Increased labeled praise & positive parenting practices, decreased negative practices in both PCIT adaptations, d ranged 70−.92 (2015)* |

||||||

| Short Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Parent Training (CEBPT) | ||||||||

| Decreased externalizing problems, d = .67, (2011) |

Decreased foster carer distress, d = .69 (2011) Improved foster carer parenting practices, d = .97 (2011) |

|||||||

| Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) | ||||||||

| Decreased posttraumatic stress, child & carer report (2014) Decreased posttraumatic stress amongst White & Black children (2009) |

Decreased externalizing problems (2014) Improved behavioral functioning, White & Black children (2000) Decreased risk behaviors in White children (2009) |

Decreased internalizing problems (2014) Decreased depression (2014) Improved emotional functioning , White & Black children (2009) |

Improved child strengths (2014) Improved child strengths, White & Black children (2009) Improved life domain functioning, White children (2009) |

|||||

| Treatment Foster Care Oregon for Preschoolers (TFCO-P) | ||||||||

| Decreased behavior problems (2000) Decreased impact of behavior problems on placement disruption (2011a) |

Decreased avoidant, attachment behaviors; children placed in program younger had greatest improvements (2007b) Less disorganized and more secure attachment (2012) |

Cortisol improvements, effect estimate ranged from −.65 to −.66, (2007a) Less blunted HPA Axis reactivity, effect estimate - .10, (2008) Prevented HPA axis dysregulation during placement changes, β = .40, (2011b) Increased regulation of diurnal cortisol slope (2012) Higher AM (β = .02) & less variable (β = .09) cortisol levels (2014a) |

Increased placement permanency (2005) Increased placement permanentce, exp(b) = 1.10, (2009b) |

Improved responsivity to performance feedback about errors, partial η2 ranged from .23 to .27, (2009a) |

Carers increased monitoring and use of reinforcement (2000) Lowered mean- levels & day-to-day variability of foster carer stress (effect estimate - .11), prevented increased foster carer stress sensitivity (2008) |

|||

Note. Data in table obtained from the published articles cited in Supplemental Material (see year and intervention to locate parent reference), as well as intervention overview articles, cited in the References list. Unless noted, all data are from studies with foster populations. RCT = randomized controlled trial. Enrollment rates reflect those enrolled in studies; may not reflect number of individuals who began interventions. When clearly available, standardized effect sizes are presented in Betas (P), exp(b), Cohen’s d, R2 or next to an ES for “effect size” or for “odds ratio” when this was the only description of the type of effect size provided by the authors.

Other notable outcomes: TFCO was less costly than services as usual (2014b); Severity of physical neglect did not moderate intervention outcomes in FHF; in KEEP, high risk children (with more than 6 behavior problems) improve > low risk children (2008a), and carer use of positive reinforcement mediated intervention outcomes (2008a); also in KEEP, carer engagement moderated risk of negative placement disruption for Hispanic children (2009) and risk of # of prior placements on increases in child behavior problems; in IY, biological parents retained positive discipline practices > foster carers (2006), while IY completers reported higher positive discipline than non-completers and African American parents reported more improvement in harsh discipline than Latino parents (2006).

see Mersky, Topitzes, Janczewski, & McNeil, 2015 for information regarding differential effectiveness of the two PCIT adaptations.

Results

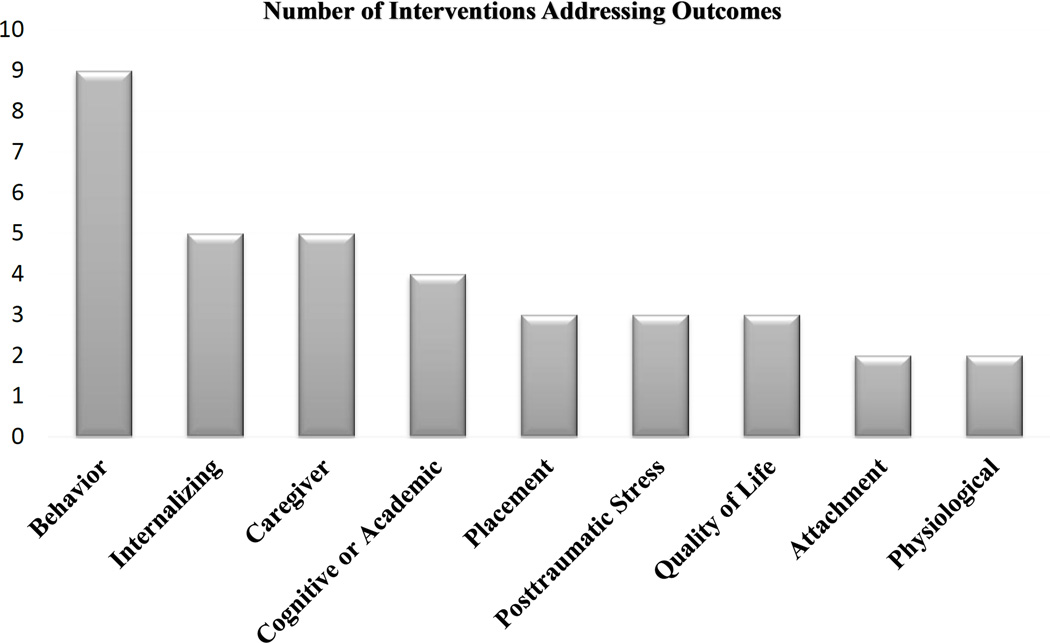

Ten possibly efficacious interventions were identified to have been evaluated with children ages 0 to 12 in foster care (Table 2) and found to yield positive mental health outcomes (Figure 2, Table 4): Attachment and Biobehavioral Catchup (ABC), Child Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF), Incredible Years (IY), Keeping Foster Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP), Kids in Transition to School (KITS), Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), Short Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Parent Training (CEBPT), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), and Treatment Foster Care Oregon for Preschoolers (TFCO-P; formerly Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers). Characteristics of each study included in this review (sample size, evaluation window, comparison groups) can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Figure 2.

Mental Health Outcomes Across all Interventions

The interventions comprised diverse characteristics (Table 3). One intervention was child-only (FHF), three were caregiver only (CEBPT, IY, & KEEP, although one IY adaptation included children), and six were caregiver-child (except one IY adaptation). Seven contained group components (CEBPT, FHF, IY, KEEP, KITS, a PCIT adaptation, and TFCO-P), and one contained elements of wraparound care (TFCO-P). Three interventions were considered to be at least somewhat preventive in nature (FHF, IY, & TFCO-P). Theoretical frameworks included Behavioral, Cognitive Behavioral, Positive Youth Development, and Psychodynamic. There was also diversity regarding service delivery site, with five interventions having at least part of their therapeutic elements delivered in the community or outside of typical health service delivery sites (FHF, KEEP, KITS, IY, & TFCO-P). Two interventions can be used with children younger than 2 years (ABC & CPP), seven with children 2 to 8 years (CPP, IY, KEEP, KITS, MTFC-P, PCIT, CEBPT, & TF-CBT), and five with preadolescents (children ages 9 to 12; FHF, IY, KEEP, TF-CBT, & CEBPT).

Table 2 summarizes the status of the evidence supporting the use of these interventions with children in foster care. Six interventions have been tested in randomized efficacy trials, while three have been tested via randomized effectiveness trials. Only one intervention has been evaluated in both a randomized efficacy and effectiveness trial in this population. No research has been conducted on the comparative effectiveness of interventions within this population. In general, there was a lack of rigorous effectiveness research, or research on how these interventions work when implemented in community settings.

Of the four interventions not originally created for foster care, three of them (IY, PCIT, & TF-CBT) were adapted to the foster context when evaluated, yielding positive outcomes. Two of these interventions (PCIT & TF-CBT) were also evaluated in non-adapted forms. The adaptation of PCIT was substantial (see Mersky, Topitzes, Grant-Savela, Brondino & McNeil, 2014 for more details), yet was rigorously tested through a randomized design. The adaptations to IY and TF-CBT were arguably more minor, while also rigorously tested using randomization. The IY adaptations mostly involved adding information related to children in foster care to session content, and the TF-CBT adaptation added an engagement intervention (elements of TF-CBT delivery were not changed). No studies compared the effectiveness of adapted versus non-adapted interventions.

As a whole, the interventions address outcomes across behavioral, internalizing, cognitive/academic, and physiological domains, amongst others (Figure 2; Table 4). Several interventions address similar outcomes; for example, nine interventions reduce or prevent behavior problems, while five reduce or prevent internalizing problems, and five improve caregiving practices. No intervention has been identified to specifically reduce symptoms of anxiety other than symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Although symptoms of anxiety were often included in broad measures of internalizing symptoms, anxiety was never evaluated independently. Moderators of intervention outcomes have only been studied in three interventions (FHF, IY, & KEEP; Table 4). In FHF, severity of neglect did not moderate outcomes (Table 4). In IY, biological parents retained positive discipline practices to a greater degree than foster caregivers, and those who completed the IY intervention reported higher use of positive discipline than non-completers (Table 4). In KEEP, high risk children were more likely to exhibit behavioral improvement than low risk children, and caregiver engagement moderated placement disruption in Hispanic/Latino children (Table 4). Only two studies presented outcomes separately for different ethnic/racial groups (studies covering CPP, IY, and TF-CBT, Table 4). Several other studies found that age was associated with outcomes, either with younger children benefitting more (TFCO-P) or less (ABC). Although there are several interventions that address mental health and developmental concerns relevant to this population, there is only a small amount of empirical guidance regarding which interventions work best for whom, given child, family, and system factors such as placement type, severity of mental health problems, race/ethnicity, age, etc.

Enrollment rates (defined as the rate of those enrolled in the research study, not necessarily of those who began the intervention) varied greatly (Table 3). KITS, the school-readiness intervention, had an enrollment rate of 57%, while FHF, the child-only intervention, had a rate of 91%. Reasons for low enrollment rates in KITS and high rates in FHF were not offered, but may be related to the fact that KITS requires a high level of caregiver involvement during a potentially busy time of year (the start of the school year), while FHF does not have a caregiver component. Enrollment was not reported in the CPP evaluation.

Reports of retention also varied widely across studies. Some studies reported how many children completed research assessments, others reported how many children completed the intervention, while still others reported the average or modal number of sessions completed by children or caregivers. Due to the difficulty comparing retention rates across studies given these differing metrics, we only report on attendance (Table 3). Reported attendance rates, however, are also difficult to compare, making it challenging to understand how well these interventions engage children and families. Only one intervention (PCIT) evaluated differences in engagement rates for different placement types, finding that more traditional foster families as opposed to kinship families were retained (Timmer, Sedlar, & Urquiza, 2004). A TF-CBT study found that when TF-CBT was augmented with an engagement intervention, enrollment and attendance rates were greater than when TF-CBT was delivered alone (Dorsey et al., 2014). This engagement intervention involved discussing caregiver perceptual barriers to engagement and caregiver goals for the child’s treatment during the first two therapist contacts with the caregiver. Although it is likely difficult to engage foster children and families in interventions, there is little empirical guidance regarding how to best engage this population. The study by Dorsey and colleagues (2014), however, is an important first step.

Discussion

This review identified which at least “possibly efficacious” mental health interventions have been evaluated with foster populations in outpatient settings. It also evaluated their characteristics, the status of their empirical support, outcomes and moderators of outcomes, and engagement rates.

We found that there is a substantial bolus of research on interventions for children in foster care. This is exciting given the arduous yet critical nature of intervention research with this population. Specifically, our review identified 10 interventions that have been evaluated with children in foster care (Table 2): Attachment and Biobehavioral Catchup (ABC), Child Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF), Incredible Years (IY), Keeping Foster Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP), Kids in Transition to School (KITS), Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), Short Enhanced Cognitive-Behavioral Parent Training (CEBPT), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), and Treatment Foster Care Oregon for Preschoolers (TFCO-P).

Most of these interventions (6) were developed for the foster population, and four interventions that were not developed for foster care have been evaluated with this population (Table 2). This is promising, because despite the need for foster care specific interventions, which are developed with clinical and systemic issues pertinent to foster care in mind (Taussig & Raviv, 2014), there is also a need to understand how and when more “mainstream” interventions may be applicable. In addition, because interventions developed for foster care serve such a targeted population, outpatient community-based mental health service sites that are not specifically focused on serving children in foster care might be less apt to adopt foster care specific interventions over more widely applicable interventions. Finally, the available set of foster care interventions does not cover the gamut of potential mental health problems experienced by children in foster care, perhaps necessitating the use of mainstream interventions.

The diversity of intervention characteristics and theoretical frameworks amongst these interventions is also encouraging (Table 3). Some interventions were child only, some were caregiver only, and most included both the caregiver and the child. Interventions employed group, individual and dyadic components. Some interventions were lengthy, spanning the course of the school year (FHF) or lasting approximately 12 months (CPP), while others were delivered in targeted daylong workshops (a PCIT adaptation). Theoretical frameworks were also diverse, as was service delivery site. This diversity amongst intervention characteristics, frameworks, and delivery site indicate that in locations in which several of these interventions are available, it may be possible to match interventions to a patient’s preferences. There has been a recent uptick in interest in patient centered outcomes research, which is based on the notion that patients should have a voice in treatment planning (Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, 2013). Now that several disparate interventions have been identified as useful within this population, foster children – who rarely get to have a voice in what happens to them (Bessel, 2001) – might begin to have the ability to engage in their own treatment planning.

Despite the positives regarding the promise of available research, the status of the evidence for interventions for children in foster care was mixed. Of the six interventions developed for foster care, only one of them (KEEP) had been evaluated via a randomized effectiveness (as opposed to efficacy) trial (Table 2). A strength of the available evidence is that many interventions developed for foster care were preventive in nature (FHF, KITS, and TFCO-P), with enrollment criteria based on age, not diagnosis. As such, the children enrolled in efficacy trials likely met criteria for a range of diagnoses, thus making the samples studied closely approximate children who present for treatment in community-based settings. However, lack of rigorous effectiveness data remains a significant limitation, as evidence-supported interventions often do not confer expected outcomes in community-based settings in populations of high risk children (Weisz et al., 2013). It has been hypothesized that this lack of effectiveness is partly due to the complex mental health problems experienced by children in high-risk populations (Weisz et al., 2013), but also due to difficulties engaging these sometimes transitory children in services (Gopalan et al., 2011), amongst other implementation problems.

Of those interventions that were not developed for foster care, only two had been evaluated via randomized effectiveness trials (IY & PCIT; Table 2), and both trials were tests of adapted versions of these interventions. Adapting interventions to the foster care context demonstrates sensitivity to the needs of this unique population. However, it does not exactly inform how well these interventions may have performed without adaption, or the extent of adaptation necessary to achieve expected outcomes. Furthermore, without manualization of such adaptations, it may be difficult for providers to know how to use these adaptations. Thus, testing adaptations is an important, while testing “how much adaptation is needed” and disseminating information about how to implement adaptations is also important.

Promisingly, two studies that were reviewed have begun to keenly test the utility of or necessity for adaptations. One study compared the effectiveness of two different PCIT adaptations (a brief versus extended version), which were both comprised of group-based caregiver training plus individual phone consultation, with a wait-list control condition (Mersky et al., 2014). Children’s behavior problems improved in both PCIT groups compared to the wait-list control, and the authors concluded that even brief adaptations of PCIT can be beneficial for this population. Another study supplemented TF-CBT with an engagement intervention, and found that children and caregivers who received the engagement intervention were more likely to complete at least four sessions, and were more likely to be retained until treatment completion (Dorsey et al., 2014). This study did not, however, find differences in outcomes across the two groups, potentially due to a relatively small sample size. Similar research, especially research showing that mental health outcomes are improved via the use of adaptations compared with intervention-as-usual, is needed.

The outcomes conferred by the 10 interventions identified by this review are broad (Figure 2, Table 4), spanning from behavioral, to emotional, to developmental, to physiological domains. Additionally, several interventions target the same outcomes. For example, nine interventions improve behavior problems, while five improve caregiver parenting skills. There has been a recent focus in federal funding agendas on comparative effectiveness research, or identifying which interventions work for whom under which circumstances (Conway & Clancey, 2009). Given the broad range of interventions that address similar outcomes within this population, it is time to begin conducting comparative effectiveness research on interventions for children in foster care. Many of the interventions that were identified by this review are likely costly, and knowing which intervention can best treat a specific child and/or family will ultimately help save time and money. It may also improve the relationship between foster children and families with mental health service providers, as getting a family the right referral, the first time, could increase their confidence in the mental health system, and even their willingness to engage.

Moderator and subgroup analyses could also help determine which interventions work best for whom (MacKinnon, 2011). These analyses are particularly warranted for children in foster care, given the diversity in placement setting, maltreatment type, severity of maltreatment or adverse childhood experiences, and mental health diagnoses within this population. Intriguing research on moderators and subgroup analyses for children in foster care was identified, perhaps signaling a need for more related research. For example, severity of neglect did not moderate outcomes in FHF, suggesting that even though FHF is a preventive intervention that enrolls children with diverse maltreatment histories, children with severe neglect histories are just as likely to benefit from the intervention as those with less severe neglect histories (Taussig, Culhane, Garrido, Knudtson, & Petrenko, 2013). An analysis of the KEEP intervention found that children with greater behavior problems were more likely to benefit from the intervention than children with less severe behavior problems (Chamberlain et al., 2008), while another analysis of KEEP showed that when caregivers were more engaged, it moderated the risk of negative placement disruption for Hispanic children (DeGarmo, Chamberlain, Leve, & Price, 2009). In TFCO-P, attachment behaviors improved most for children who were enrolled at younger ages (Fisher & Kim, 2007), and an ABC study found that behavior problems improved for toddlers, not infants, as a result of intervention (Dozier et al., 2006). Finally, outcomes from a pre-post trial of CPP and TF-CBT were presented per racial/ethnic group, thus clarifying for which groups certain outcomes can be expected (Weiner, Schneider, & Lyons, 2009). It is likely that these findings are only the beginning of what can be learned about how these interventions benefit particular children and families, and the timing of when these interventions are most beneficial.

Findings regarding engagement were sparse and difficult to synthesize (Table 3). Most articles reported some information on engagement, such as enrollment rates, retention rates, or attendance rates. However, enrollment rates were often reported as who was enrolled into research studies, not who actually began the interventions. Similarly, retention was frequently reported as who was retained in the studies, not as who completed the interventions. Attendance rates, when reported, were also reported using varying metrics. For example, some authors reported the average number of sessions attended, while others stated that a certain percentage of participants completed “at least” a certain amount of sessions. Thus, it is difficult to understand how well specific interventions engaged children and families, which children and families were most engaged in specific interventions, and reasons for weak or strong engagement in specific interventions. Three studies did particularly highlight certain aspects of engagement, with important findings. Timmer, Sedlar and Urquiza (2004) found that kin caregivers were more likely than nonkin caregivers to complete a non-adapted version of PCIT. Degarmo and colleagues (2009) found that caregiver engagement decreased the likelihood of placement disruption for Hispanic children, and Dorsey and colleagues found that when TF-CBT is supplemented with an engagement intervention, families are more likely to be retained (2014). Yet, significant questions regarding engagement remain, including which children/families are best engaged in each intervention, whether engagement interventions improve mental health outcomes, and whether engagement interventions should supplement all interventions used with this population, or just those that were not developed for this population.

Now that there is evidence that a range of interventions are useful in ameliorating mental health problems experienced by children in foster care, it is time to identify which interventions work for whom, under which circumstances (Conway & Clancey, 2009; Weisz et al., 2013). For example, there is a need for research that can help providers determine whether a nine-year-old in foster care with some elevated symptoms of posttraumatic stress might be best suited for FHF or TF-CBT – the two interventions that reduce symptoms of posttraumatic stress for school-aged children in foster care (e.g., Willis & Holmes-Rovner, 2006). Another example is whether a young child with behavior problems might benefit most from TFCO-P or PCIT, both interventions that reduce behavior problems for preschoolers in foster care. Also, there are a great number of interventions that treat behavior problems within this population, perhaps signaling that with additional research, referrals can be made not only based on a patient’s primary mental health problems, but also on patient characteristics. Similarly, there is a need to know more about how factors related to engagement should be weighed during the referral process. For example, FHF had high enrollment and attendance rates. Yet, it is preventive intervention, and may not confer mental health outcomes for children with extremely high levels of risk, despite engaging them. We also need more information on the appropriate timing and sequencing of intervention approaches given a child’s developmental risk profile (Perry & Dobson, 2013). Finally, future intervention research should not be limited to these 10 interventions. There is a great need to continue to develop targeted interventions for this population, and to test the effectiveness of existing interventions with this population.

Although the findings from this study may be useful in helping guide future intervention research for children in foster care, there are several important limitations. Despite efforts to exclude studies with high risk of bias, potential for bias remains, particularly because we chose to include less-rigorous evaluations of interventions within foster care as long as the intervention was supported by an RCT in at least one population. Thus, outcomes from these studies may not generalize under other conditions. We did only include studies that were published in peer-reviewed journals or dissertations, yet this creates publication bias. Specifically, studies with positive outcomes were likely identified more often than ones with negative or harmful results. We caution readers not to assume that the reviewed interventions have only yielded positive results, as they may have yielded null or even harmful results in unpublished studies. Another limitation of the study is the narrative nature of the analysis. We chose this strategy given that we planned to include information from less-rigorous evaluations of interventions within this population. Our goal was to summarize the available information, not to calculate quantitative treatment effects.

The ultimate goal of this paper was to improve the implementation of interventions for children in foster care. The service systems in which children in foster care receive mental health treatment are as diverse and complex as the clinical problems children in foster care face. No two children have the same “foster care” experience. As such, flexibility in treatment planning must be improved. We believe that continued research on foster care interventions can help make the goal of flexible treatment planning a reality. Moreover, the field of foster care intervention research is growing. Continued rigorous intervention research for children in foster care is critical, alongside equally rigorous research regarding how to implement these interventions effectively. With ongoing research with this population, the hope is that future studies evaluating the utility of community-based mental health services for children in foster care will show that indeed, receipt of services is beneficial for children in foster care.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Children in foster care have high rates of adverse childhood experiences and are at risk for mental health problems.

This review was conducted on mental health interventions for children, ages 0 to 12, in foster care.

Ten interventions were identified, with diverse outcomes, including mental health and physiological.

Most interventions have yet to be rigorously evaluated in community-based settings with children in foster care.

Little research has been conducted on child and family engagement within these interventions, and there is a need for more research on moderators of intervention outcomes and subgroups that benefit most from these interventions.

Future research should focus on developing and testing more interventions with this population, and identifying which interventions work best for whom.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded under grant T32MH015442, institutional postdoctoral research training program, for Dr. Hambrick. This research was also supported in part by a postdoctoral research grant from the Haruv Institute given to the second author. Dr. Hambrick is now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Missouri – Kansas City.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bellamy JL, Gopalan G, Traube DE. A national study of the impact of outpatient mental health services for children in long-term foster care. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;15:467–479. doi: 10.1177/1359104510377720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessell S. Participation in decision-making in out-of-home care in Australia: What do young people say? Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:496–501. [Google Scholar]

- Bruskas D, Tessin DH. Adverse childhood experiences and psychosocial well-being of women who were in foster care as children. The Permanante Journal. 2013;17:e131–e141. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, Barth RP, Kolko DJ, Campbell Y, Landsverk J. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanueva C, Ringeisen H, Wilson E, Smith K, Dolan M. NSCAW II Baseline Report: Child Well-Being. OPRE Report #2011-27b. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, Laurent H, Landsverk JA, Reid JB. Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Kendall PC. Positive association of child involvement and treatment outcome within a manual-based cognitive-behavioral treatment for children with anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:821–829. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway PH, Clancey C. Comparative-effectiveness research - Implications of the federal coordinating council’s report. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:328–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0905631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney M, Dworsky A, Brown A, et al. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Chamberlain P, Leve LD, Price J. Foster parent intervention engagement moderating child behavior problems and placement disruption. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19:423–433. doi: 10.1177/1049731508329407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Conover KL, Revillion Cox J. Improving foster parent engagement: using qualitative methods to guide tailoring of evidence-based engagement strategies. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43:877–889. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.876643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Pullman MD, Berliner L, Koschmann E, McKay M, Deblinger E. Engaging foster parents in treatment: A randomized trial of supplementing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with evidence-based engagement strategies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:1508–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lindhiem O, Gordon MK, Manni M, Sepulveda S, Ackerman J. Developing Evidence-Based Interventions for Foster Children: An Example of a Randomized Clinical Trial with Infants and Toddlers. Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62:767–785. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Chapman MV, Phillips SD, Angold A, Costello EJ. Use of mental health services by youth in contact with social services. Social Service Review. 2001;75:605–624. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Kim HK. Intervention effects on foster preschoolers’ attachment-related behaviors from a randomized trial. Prevention Science. 2007;8:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: Methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implementation Science. 2010;5 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, Aarons GA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:409–418. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido EF, Culhane SE, Raviv T, Taussig HN. Does community violence exposure predict trauma symptoms in a sample of maltreated youth in foster care? Violence and Victims. 2010;25:755–769. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.6.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Fraser J, Lloyd SW, Murphy RA, Crowson MM, Casanueva C, Zolotor A, Coker-Schwimmer M, Letourneau K, Gilbert A, Swinson Evans T, Crotty K, Viswanathan M. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, No. 89. Rockville, MD: 2013. Child Exposure to Trauma: Comparative Effectiveness of Interventions in Addressing Maltreatment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Bannon W, Dean-Assael K, Fuss A, Gardner L, LaBarbera B, McKay M. Multiple Family Groups: An Engaging Intervention for Child Welfare-Involved Families. Child Welfare. 2011;90(4):135–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Leslie LK. Predictors of outpatient mental health service use - The role of foster care placement change. Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6:127–141. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000036487.39001.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Hurlburt MS, Zhang J, Barth RP, Leslie LK, Burns BJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents referred for child welfare investigation. A national sample of in-home and out of-home care. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:48–63. doi: 10.1177/1077559509337892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kools SM. Adolescent identity development in foster care. Family Relations. 1997;46:263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Chamberlain P, Landsverk JA, Fisher PA, Volstanis P. Practitioner review: Children in foster care - vulnerabilities and evidence-based interventions that promote resilience processes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:1197–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange S, Shield K, Rehm J, Popova S. Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in child care settings: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e980–e995. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Zhang J. Relationship between entry into child welfare and mental health service use. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:981–987. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, Landsverk J, Barth R, Slymen DJ. Outpatient mental health services for children in foster care: A national perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:699–714. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Integrating Mediators and Moderators in Research Design. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21(6):675–681. doi: 10.1177/1049731511414148. http://doi.org/10.1177/1049731511414148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae JS, Barth RP, Guo S. Changes in maltreated children’s emotional- behavioral problems following typically provided mental health services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(3):350–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Grant-Savela SD, Brondino MJ, McNeil CB. Adapting parent-child interaction therapy to foster care: Outcomes from a randomized trial. Research on Social Work Practice. 2014:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Southam-Gerow MA, Allin RB. Who stays in treatment? Child and family predictors of youth client retention in a public mental health agency. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2008;37:153–170. doi: 10.1007/s10566-008-9058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Working Group on Foster Care and Education. Fostering success in education: National factsheet on the educational outcomes of children in foster care. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.cacollegepathways.org/sites/default/files/datasheet_jan_2014_update.pdf.

- New York State Office of Children and Family Services. Ten for 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.ocfs.state.ny.us/main/reports/vera_tenfor2010.pdf.

- Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Patient Centered Outcomes Research. 2013 Nov 7; Retrieved from http://www.pcori.org/research-results/patient-centered-outcomes-research.

- Perry BD, Dobson C. The Neurosequential Model (NMT) in maltreated children. In: Ford J, Courtois C, editors. Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Children and Adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman K, Taussig H. Mental health treatment of child abuse and neglect: The promise of evidence-based practice. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2009;56:417–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Johnson AB, Pears KC, Fisher PA, DeGarmo DS. Child maltreatment and foster care: Unpacking the effects of prenatal and postnatal parental substance use. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:150–160. doi: 10.1177/1077559507300129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Stormshak E, Chamberlain P, Whaley RB. Placement disruption in treatment foster care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2001;9:200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Zima BT, Elliott MN, Burnam MA, Shahinfar A, Fox NA, Leavitt LA. Violence exposure among school-age children in foster care: Relationship to distress symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:588–594. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200105000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovall-McClough KC, Dozier M. Forming attachments in foster care: Infant attachment behaviors in the first two months of placement. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:253–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussig HN, Culhane SE, Garrido E, Knudtson MD, Petrenko CLM. Does Neglect Moderate the Impact of an Efficacious Preventive Intervention for Maltreated Children in Foster Care? Child Maltreatment. 2013;18(1):56–64. doi: 10.1177/1077559512461397. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077559512461397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussig HN, Raviv T. Handbook of Child Maltreatment. Springer; 2014. Foster care and child well-being: A promise whose time has come; pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Timmer SG, Sedlar G, Urquiza AJ. Challenging children in kin versus nonkin foster care: Perceived costs and benefits to caregivers. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9:251–262. doi: 10.1177/1077559504266998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. National Adoption and Foster Care Statistics Report. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport22.pdf.

- Weiner DA, Schneider A, Lyons JS. Evidence-based treatments for trauma among culturally diverse foster care youth: Treatment retention and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:1199–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Hawley KM, Jensen-Doss A. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: A multilevel meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;70:750–761. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis CE, Holmes-Rovner M. Integrating Decision Making and Mental Health Interventions Research: Research Directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:9–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.