Abstract

Background

Transient starch provides carbon and energy for plant growth, and its synthesis is regulated by the joint action of a series of enzymes. Starch synthesis IV (SSIV) is one of the important starch synthase isoforms, but its impact on wheat starch synthesis has not yet been reported due to the lack of mutant lines.

Results

Using the TILLING approach, we identified 54 mutations in the wheat gene TaSSIVb-D, with a mutation density of 1/165 Kb. Among these, three missense mutations and one nonsense mutation were predicted to have severe impacts on protein function. In the mutants, TaSSIVb-D was significantly down-regulated without compensatory increases in the homoeologous genes TaSSIVb-A and TaSSIVb-B. Altered expression of TaSSIVb-D affected granule number per chloroplast; compared with wild type, the number of chloroplasts containing 0–2 granules was significantly increased, while the number containing 3–4 granules was decreased. Photosynthesis was affected accordingly; the maximum quantum yield and yield of PSII were significantly reduced in the nonsense mutant at the heading stage.

Conclusions

These results indicate that TaSSIVb-D plays an important role in the formation of transient starch granules in wheat, which in turn impact the efficiency of photosynthesis. The mutagenized population created in this study allows the efficient identification of novel alleles of target genes and could be used as a resource for wheat functional genomics.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3724-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wheat, TILLING, Mutant, TaSSIVb-D, Gene expression, Starch granule

Background

Starch granules in plants are classified into two types according to their physiological role. Some starch granules are stored for long periods in reserve tissues as storage starch. This type of starch is an important source of carbohydrates for human beings. Other types of starch are stored temporarily as transient starch to provide carbon and energy for plant growth. Transient starch is synthesized in chloroplasts during the day and consumed during the night. Storage starch granules are synthesized in the plastid stroma by joint action of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylases (AGPase), starch synthases (SS), starch branching enzymes (SBE), starch debranching enzymes (DBE) and their isoforms; however, the synthesis and regulation of transient granules hold a specific feature [1]. Some synthase isoforms that synthesize storage starch are different from those that synthesize transient starch.

AGPase is the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of starch, it catalyzes the synthesis of ADP-glucose, which is the substrate of amylose starch, and over expression of the AGPase gene enhances the rate of starch biosynthesis [2–4]. Amylose, one of the main forms of starch, is synthesized from the substrate, ADP-glucose, by granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS). The isoform GBSS2 is responsible for amylose synthesis in leaves and other non-storage tissues [5–8], whereas amylopectin, the other major form of starch, is synthesized by the coordinated actions of AGPase, SS, and SBE. Five soluble SS isozymes, SSI, SSII, SSIII, SSIV, and SSV are found in plant genomes [9, 10]; and among them, SSI, SSII, and SSIII are involved in amylopectin elongation [11]. Isoform SSI is highly expressed in plant leaves [12, 13]. Two or three isoforms of SSII and SSIII are found in the genomes of different species, and at least one isoform is expressed in leaves and regulates starch granule biosynthesis [14–17]. Only one SSIV isoform is found in the Arabidopsis genome; AtSSIV is involved in the initiation of starch granule formation in leaves [18, 19]. Overexpression of AtSSIV increases the levels of starch accumulation by 30–40% and results in a higher rate of growth [20]; SSIV mutants have remarkably decreased numbers of granules and abnormal granules [18, 19, 21].

The functions of SSIV isozymes in the leaves of cereal crops are not as clear as in Arabidopsis. Two SSIV isoforms, SSIVa and SSIVb, are found in rice. SSIVa is mainly expressed in the endosperm and is responsible for starch accumulation in seeds, whereas SSIVb is mainly expressed in leaves at early development stages and is responsible for leaf granule biosynthesis [12, 14, 22]. It also has overlapping and crucial roles with SSIIIa in rice seeds in determining granule morphology and in maintaining the amyloplast envelope structure [23]. ZmSSIV is highly expressed in the embryo, endosperm and pericarp in maize. In wheat, only one isoform of SSIV has been identified until now. This gene is located on the long chromosome arm of homologous group I and shows high similarity with OsSSIVb, so this isoform is named TaSSIVb [12, 24]. TaSSIVb is preferentially expressed in leaves and is not regulated by the circadian clock [24]. TaSSIVb is also highly expressed at the middle stages of seed development [25, 26]; however, the impact of TaSSIVb on wheat leaf and seed granule characteristics at different growth stages have not yet been reported due to the lack of mutant lines.

TILLING (Targeting-Induced Local Lesions IN Genomes) is a powerful approach for novel allele identification and has been used to screen mutagenized plant populations for novel alleles of target genes [27–34]. Hundreds of missense and nonsense mutant alleles of key starch synthesis-related wheat genes, such as TaSSII, TaSBEIIa, TaSBEIIb, have been identified using this platform [35, 36]. A hexaploid wheat line containing two waxy homozygous mutations created through TILLING and a pre-existing deletion of a third waxy homoeolog displays a near-null phenotype [37]. Novel alleles of TaSBEII have been identified in both durum wheat and bread wheat. Double mutant lines combining a TaSBEIIa-A mutation with a TaSBEIIa-B mutation in durum wheat and triple mutant lines combining mutations in TaSBEIIa-A, TaSBEIIa-B with TaSBEIIa-D have a significant increase in both amylose and resistant starch content [38–42]. Using this approach to identify novel alleles of TaSSIVb would be helpful in characterizing its role in transient starch granule synthesis in wheat leaves.

In this paper, we used the TILLING approach to identify novel alleles of TaSSIVb–D with mutations in functional regions in an Ethyl methanesulphonate (EMS) mutagenized population derived from an elite hexaploid wheat cultivar. Homozygous mutants were used to investigate the specific role of TaSSIVb-D in starch granule synthesis in leaves at different stages of growth. We found that TaSSIVb-D mutations decrease gene expression and the number of starch granules in leaves.

Results

Novel alleles of TaSSIVb-D in a mutagenized population

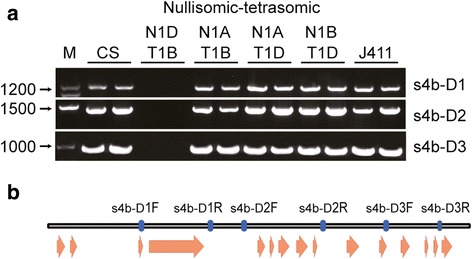

Three primer sets corresponding to TaSSIVb-D were designed for allele mining (Table 1), and their specificities were validated using nullisomic-tetrasomic lines (Fig. 1a). The location of these primers on the TaSSIVb-D sequence is shown in Fig. 1b.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for allele mining

| Name | Forward (5’-3’) | Reverse (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| s4b-D1 | ACTAAAACCCACTTTGCGAC | GGTAGGAATGATACAGAACACC |

| s4b-D2 | CTGCAAAAAATTGTCTAAAAGCTAC | CATGCTTTGAAATTATCTACTTTCG |

| s4b-D3 | ACCAGAAATTCAGGTGCGTT | TGAGTCGTGTTGTGCCCG |

Fig. 1.

Validation of subgenome-specific TaSSIVb-D primers using the Chinese Spring nullisomic-tetrasomic lines. a Products from the Chinese Spring (CS), nullisomic-tetrasomic lines (N1AT1B, N1AT1D, N1BT1D and N1DT1B) and wild type (J411) amplified using the three different sets of TaSSIVb-D-specific primer pairs shown in b. TaSSIVb-D is absent from N1DT1B. b Diagram of D subgenome primers. The black rectangle represents the gene sequence; orange arrowheads indicate exon regions; blue rectangles represent the location of each primer

In the mutagenised population, 54 mutations were identified with a mutation density of 1/165 Kb. Among these mutations, 52 are G to A (61.12%) or C to T (35.19%) transition point mutations, and the other 2 are T insertions. Of these mutations, 26 are in the coding region (Table 2), including 1 nonsense mutation (E054-13), 15 missense mutations and 10 silent mutations. The remaining 26 are located in introns and include 2 splice junction mutations.

Table 2.

Mutations identified in the coding region of the TaSSIV b-D gene

| Line | Allele | Mutation Type | Effect | PSSM | SIFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E334 | G1783A | Silent | |||

| E1239 | G1813A | Missense | E181K | 4.4 | 0.6 |

| E469 | G1822A | Missense | E183K | −6 | 0.42 |

| E939 | G1848A | Silent | |||

| E1337 | G1863A | Silent | |||

| E2-2-226 | T1880C | Missense | L203S | 26.7 | 0 |

| E2-2-437 | T1880C | Missense | L203S | 26.7 | 0 |

| E468 | G1890A | Silent | |||

| E1245 | G1920A | Silent | |||

| E391 | G1975A | Missense | D235N | ||

| E137 | G2008A | Missense | D246N | 0.4 | 0.96 |

| E054-13 | C2077T | Nonsense | Q269-Stop | ||

| E2-2-193 | C2143T | Missense | L291F | 0.6 | 0.02 |

| E2-2-95 | C2152T | Missense | L294F | ||

| E570 | A2219G | Missense | Q316R | 8.4 | 0 |

| E1347 | C2353T | Silent | |||

| E783 | G2402A | Missense | S377N | ||

| E236 | G2413A | Silent | |||

| E996 | C3516T | Silent | |||

| E2-2-181 | G3536A | Missense | V469I | ||

| E054-9 | C3740T | Intronic | |||

| E1226 | G3932A | Missense | V550I | 0.9 | 0.09 |

| E972 | C3950T | Missense | H556Y | 27.5 | 0 |

| E930 | G5872A | Silent | |||

| E1373 | C5878T | Silent | |||

| E1137 | G6327A | Missense | S833N | 12 | 0 |

Nucleotide changes are numbered relative to the start codon ATG

Using SIFT program, five missense mutations (E2-2-226 and E2-2-437, E2-2-193, E570, E972, E1137) are predicted to have a severe impact on protein function. Based on the PSSM program, three missense mutations (E2-2-226 and E2-2-437, E972, E1137) are predicted to have a severe impact. As the nonsense mutant E054-13 results in the loss of both the starch catalytic domain and glycosyltranferase domain, it might have a severe impact on protein function. Because the E1137 mutation is located in the glycosyltranferase domain which has less similarity with other SS isoforms [24], and might have distinct functions from other starch synthases, mutants E1137 and E054-13 were selected for analysis of gene expression and starch granule number.

The expression of TaSSIVb in mutant leaves at different growth stages

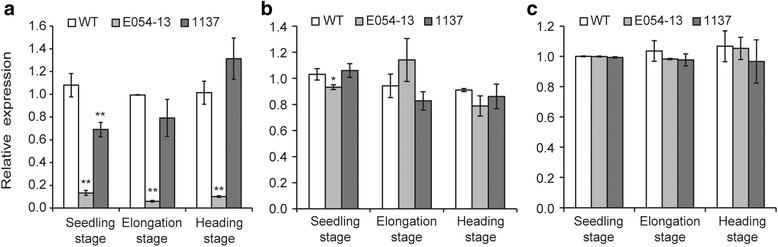

Specific primer sets for each sub-genome (Additional file 1: Table S1, Additional file 2: Figure S1) were used to analyze the pattern of TaSSIVb gene expression. In wild type, gene expression profiling revealed non-significant differences in expression between different growth stages (Fig. 2). In the mutants, TaSSIVb-D was down-regulated, and TaSSIVb-A and TaSSIVb-B did not show significant compensatory responses. The expression of TaSSIVb-D in the nonsense mutant E054-13 was reduced by ~8-fold compared with the wild type at all three growth stages, whereas in E1137, its expression level gradually increased with plant growth and only showed a significant reduction (36.12%) at the seedling stage (Fig. 2a). In contrast, no significant differences in the expression of TaSSIVb-A (Fig. 2b) and TaSSIVb-B (Fig. 2c), were detected in the two TaSSIVb-D mutants at all three stages, except for TaSSIVb-A expression in the E054-13 mutant at the seedling stage (9.55% reduction).

Fig. 2.

Expression patterns of the three homeologous TaSSIVb genes in leaves at different stages. a Relative expression level of TaSSIVb-D; b Relative expression level of TaSSIVb-A; c Relative expression level of TaSSIVb-B. Error bars represent standard deviation; WT: wild type; * means significantly different from WT at the P = 0.05 level and ** means significantly different from WT at the P = 0.01 level based on Student’s t test

Variation in the number of starch granules in the chloroplast

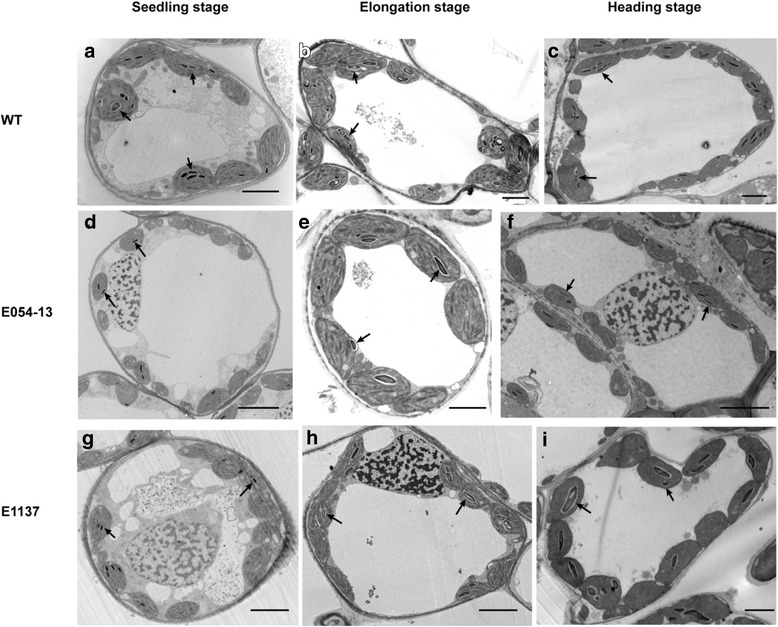

We investigated starch granule characteristics in the chloroplasts of wild type and the two mutants at three growth stages (Fig. 3). Granule number varied plast by plast in each genotype, with numbers ranging from 0 to 8 and more than 90% of chloroplasts contained no more than 4 granules (Additional file 1: Table S2). The difference between the wild type and mutants was mainly in the number of chloroplasts containing no more than 4 granules.

Fig. 3.

Starch granules observed in the chloroplasts of wild type (a, b, c) and TaSSIVb-D E054-13 (d, e, f) and E1137 (g, h, i) mutants by transmission electron microscopy. Arrows indicate starch granules, bars = 5 μm

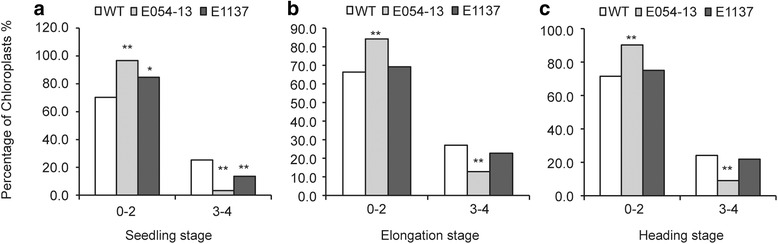

The biggest difference in granule number per chloroplast was observed at the seedling stage, and mutation of TaSSIVb-D led to a reduction in granule number. The percentage of chloroplasts with 0–2 granules in both mutants, E054-13 (96.70%) and E1137 (84.70%), were significantly higher compared with wild type (70.30%) (Fig. 4), whereas at the elongation and heading stages, the difference between E1137 and wild type became smaller; only the E054-13 mutant had a significantly higher percentage of chloroplasts with 0–2 and 3–4 granules (17.74% and 18.72% higher than wild type, respectively). In contrast, the percentage of chloroplasts containing 3–4 granules was lower in the mutants than in wild type. At the seedling stage, the percentage of chlorplasts in E054-13 and E1137 with 3–4 granules was 22.00% and 10.3% lower than wild type, respectively. At the elongation and heading stages, only the E054-13 mutant was significantly different from wild type; the percentage of chlorplasts with 3–4 granules was 14.26% and 15.05% lower than wild type, respectively. The observation of the chloroplast granule number phenotype at all stages for the E054-13 mutant and only at the seedling stage for the E1137 mutant is consistent with the lower levels of TaSSIVb-D gene expression in the mutants at these stages (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of chloroplasts in wild type (WT) and TaSSIVb-D mutants (E054-13 and E1137) containing 0–2 and 3–4 granules at three different growth stages. a Seedling stage; b Elongation stage; c Heading stage. The percentage of chloroplasts equals the number chloroplasts containing 0–2 and 3–4 starch granules divided by the total number of chloroplasts observed. * means significantly different from WT at the P = 0.05 level and ** means significantly different from WT at the P = 0.01 level

Photosynthesis parameters and the efficiency of PSII

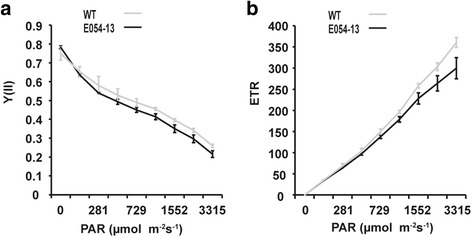

As transient starch in chloroplasts provides carbon and energy for plant growth, we deduced that photosynthesis might be affected by reduced granule numbers. Granule numbers in the mutant E054-13 were more severely reduced than those in E1137, and the impact on photosynthesis parameters are expected to be more severe. Therefore, photosynthesis parameters in the mutant E054-13 and the wild type at the heading stage were compared to determine the impact of reduced granule number. We found that the maximum quantum yield (F v/F m) and yield of PSII (Y(II)) of E054-13 were significantly lower than in wild type (Table 3), and differences between the mutant and wild type in both Y(II) and electron transport rate (ETR) increased with increasing photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) (Fig. 5). As Y(II) provides the effective quantum yield and could be used to estimate the effective portion of absorbed quanta; while ETR provides information for plant stress reaction, so the results indicates that mutation of TaSSIVb-D leads to a decrease in relative quantum yield and has a negative effect on PSII efficiency.

Table 3.

Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in the TaSSIVb-D E054-13 nonsense mutant at the heading stage

| Genotype | Y(II) | F v/F m |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 0.641 ± 0.0019 | 0.818 ± 0.0175 |

| E054-13 | 0.617 ± 0.0020 ** | 0.622 ± 0.0274 ** |

Y(II) and F v/F m were measured in dark-adapted plants, and Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) equals 281. Values are means ± standard deviation

** significantly different from the wild type at the P < 0.01 level based on Student’s t test

Fig. 5.

Y(II) (a) and ETR (b) fast light curves for wild type and the TaSSIVb-D E054-13 nonsense mutant at the heading stage. Error bars represent standard deviation

Discussion

Conserved and functional regions of TaSSIVb

As one of the isoforms of the soluble starch synthesis family, wheat SSIV contains the starch catalytic domain (GT-5) and glycosyltranferase domain (GT-1). GT-5 (amino acids 422–661) is more conserved than GT-1 (amino acids 706–886) between SS isoforms [24]. Two mutations that we identified in this study, E972 and E1137, are located in GT-5 and GT-1, respectively, and in the wild type these amino acids are involved in the formation of β-sheets (data not shown). In contrast the N-terminus (amino acids 1–405) is distinct from other SS isoforms, and this region contains two coiled-coil domains and a 14-3-3-protein binding site [24]. The missense mutation E2-2-226 and the truncation mutation E054-13 are located in this region. These novel alleles could be very useful in understanding the specific functions of SSIV in starch granule synthesis in wheat. The gene expression patterns and alteration of granule number in the E1137 and E054-13 mutants demonstrate the important roles of these predicted functional regions. The E054-13 truncation mutation has a more severe effect than the missense mutation; TaSSIVb gene expression is reduced by 5 ~ 13-fold compared with E1137 (Fig. 2), and granule number is also significantly decreased compared with E1137 (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Expression of TaSSIVb homoeologs

Wheat has three sub-genomes, and the literature shows that the contribution of each homeologous gene can be different. For example, of the three SSIIa genes, SSIIa on the B genome has the largest contribution to amylopectin structure than those on the other two genomes [43]. Each waxy gene encoding GBSSI has different effects on amylopecitin characteristics [37, 44, 45]. SS isoform SSIV is encoded by three homeologous genes located on group I chromosomes [24] and the effect of each gene and their interactions is not clear. Here we designed homeologous-specific primers to determine the gene expression patterns of the three SSIV genes. In TaSSIVb-D mutants, decreased expression of TaSSIVb-D did not result in significant changes in the expression of TaSSIVb-A or TaSSIVb-B. This is similar to what was observed in the single null mutant of SBEIIa; a mutation in one sub-genome does not result in appreciably different expression in the other two sub-genomes [46]. However, the identification of mutations in TaSSIVb-A and TaSSIVb-B is needed to analyze the interaction between homoeologous copies or their dosage effects.

Expression of TaSSIV-D in wheat leaves

The function of AtSSIV, which it is highly expressed in leaves in Arabidopsis is very well understood. In wheat, the expression of TaSSIVb is tissue-dependent, and is much more highly expressed in leaves than in the endosperm [24]. Our results are consistent with these reports; all three homeologous genes are highly expressed in leaves during the entire growth period. There is also evidence that TaSSIVb is expressed during seed development [24–26]. In ongoing research we are investigating the accumulation of storage starch in both the E054-13 and E1137 mutants to elucidate the role of TaSSIVb in storage starch synthesis.

Starch granule synthesis

Starch granules are initiated early in the development of young leaves in Arabidopsis. Because more starch granules are observed in immature leaves than in mature leaves [47], it is believed that SSIV functions in granule initiation at earlier growth periods [21]. The ssIV mutant in Arabidopsis has reduced granules in most chloroplasts [18, 21]. The results of this study demonstrate that in young wheat leaves TaSSIV-D has a function similar to AtSSIV, and it is involved in initiation of transitory starch synthesis. At the seedling stage, the expression patterns of both the E054-13 and E1137 TaSSIV-D mutants are down regulated. In the E1137 mutant, the significant reduction of granule number is only observed when the expression of TaSSIV-D is reduced; while in the nonsense mutant, starch granules are reduced at all the three stages. This indicates that reduction of starch granule number results from the mutation of TaSSIV-D and not other genes.

Effect of homeologous genes

In many cases, homeologous genes from different sub-genomes of wheat have dosage effects on phenotypes. Only double or triple mutants of SSIIa have severe effects on starch properties [48, 49], and single-gene mutants do not show significant phenotypes [38]. However in single TaSSIV-D gene mutants, gene expression level, granule number, relative quantum yield and PSII efficiency are significantly reduced with respect to the wild type. It has been reported that single mutants of the genes SBEIIa and gpc (grain protein content) also show significant phenotypic differences compared with the wild type [46, 50], so not only double and triple mutants, but also single mutants can lead to phenotypic changes in hexaploid wheat.

Relationship between transient starch content and photosynthesis

It has been reported that the capacity for starch synthesis and the rate of photosynthesis are positively correlated [51]. A starchless tobacco mutant shows about 50% inhibition of maximum photosynthetic capacity [52]. Mutation of SSIV in Arabidopsis also has negative effects on photosynthesis efficiency [53]. Our SSIV mutant in wheat shows the same effects; photosynthesis efficiency is significantly reduced. This is likely because SSIV mutants accumulate high concentrations of the substrate ADPglucose [21], which leads to photooxidative stress and decreased photosynthesis efficiency [53].

Conclusions

We identified novel alleles, including missense and nonsense mutations, of the starch synthesis gene, TaSSIVb-D. Gene expression, granule number and photosynthetic parameters are down-regulated or reduced in the missense mutant E1137 and the nonsense mutant E054-13, and the impact of E054-13 is much more severe than that of E1137. This demonstrates TaSSIVb-D plays an important role in the formation of transient starch granules in wheat, and mutation of TaSSIVb-D results in remarkable reduction in transitory starch granules in leavies. The mutagenized population generated in this study could be used as a resource for gene functional research.

Methods

Materials

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivar Jing411 was used as the wild type (WT) to create the mutagenized population. Homozygous mutant lines grown in the field with normal management were used for RT-qPCR and phenotyping.

Development of the wheat TILLING population

Seeds from the wild type Jing411 were soaked in tap water for 10 h at 20°C, then incubated in 1.5% EMS in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH7.0) for 4 h or 6 h at 20°C. This was followed by washing with running tap water for 4 h at room temperature. The mutagenized seeds (M1 generation) were planted directly in the field and self-fertilized. The M2 was developed using the single-seed descent (SSD) method.

The mutagenized population consists of 3058 M2 plants, including 1441 individuals from the 4 h 1.5% EMS treatment and 1617 from the 6 h treatment. A young leaf from each individual was sampled at the seedling stage for genomic DNA extraction using the DNA-quick Plant System kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). DNA concentration was measured with the NanoDrop2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the final concentration was adjusted to 50 ng/μl. Individual DNA samples were pooled 2-fold into 96-well plates for TILLING screening, which was done according to Till et al. [54].

Primer design

The sequence of TaSSIVb (DQ400416) was downloaded fromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/DQ400416, and the sequences of TaSSIVb-A, TaSSIVb-B and TaSSIVb-D were obtained through alignment with long arm of chromosome 1A, 1B and 1D (https://wheat-urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Seq-Repository). TaSSIVb-D was used as the target gene for mining and phenotyping novel alleles. Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA) was used to design homoeolog-specific TILLING and qPCR primers (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1), and their specificities were validated using Chinese Spring nullisomic-tetrasomic lines (N1AT1B, N1AT1D, N1BT1D and N1DT1B; Fig. 1a and Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Mutation screening

Each primer used for TILLING detection was synthesized with and without fluorescent dye label. Unlabeled primers (Sangon Biotech, China), forward primers labeled with the fluorescent dye IRD700 and reverse primers labeled with the fluorescent dye IRD800 (Bioneer, China) were mixed with the ratio of unlabeled forward: labeled forward: unlabeled reverse: labeled reverse = 4: 1: 1: 4. PCR amplification and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were carried out as previously described [54]. Identified mutations were sequenced to verify nucleotide variation. Mutation density was calculated by dividing the total number of mutations by the total length of the sampled DNA sequence (length of the amplified fragment × number of individuals sampled). Totally 3058 individual plants were screened for each primer set, and the amplicon size of primer set s4b-D1, s4b-D1 and s4b-D1 was 1191, 1361 and 960 bp respectively. As DNA products at the top and bottom of the gel were difficult to detect, we subtracted 100 bp from the 5’ terminus and 100 bp from the 3’ terminus of each fragment.

The PARSESNP (Project Aligned Related Sequences and Evaluate SNPs; http://blocks.fhcrc.org/proweb/parsesnp/) and SIFT (Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant; http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) programs were used to predict the severity of each mutation. Mutations with PSSM >10 or SIFT <0.05 are predicted to have a severe effect on protein function [55, 56].

RT-qPCR

The effects of mutations on the expression of TaSSIVb gene homoeologs was evaluated for leaves at the seedling, elongation and heading stages. Total RNA was extracted from three individual plant leaves, and cDNA was synthesized using the FastQuant RT kit (With gDNase, Tiangen Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis was done for three biological replicates per genotype with three technical replicates for each biological replicates, and their concentrations measured with the NanoDrop2000 spectrophotometer, the same volume and concentration of normalized template was used for the next step experiment. RT-qPCR was performed on a CFX96 system using the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix kit (Bio-Rad), PCR was performed at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s, and 72°C for 10 s, and then a melt curve stage. Concentration of each primer was 0.3 μmol, amplification efficiency of the three genes ranged from 97% to 100%. The actin gene used as a control was the same as described by Gu et al. [57]. The relative expression level was calculated with ΔΔCt method according to the CFX96 manual, data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using Microsoft Excel software.

Electron microscopy

At the seedling, elongation, and heading stages, leaves of mutants and WT at the same developmental stage were sampled with 3 replicates for transmission electron microscope analysis. Each sample was processed as described in Guo et al. [58] and photographed with a transmission electron microscope (HT-7700, Hitachi, Japan). Starch granule numbers per chloroplast were calculated, and data were analyzed using the SPSS software [59].

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

A pulse amplitude modulation fluorometer (MINI-PAM, Heinz Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) was used to measure chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. At the seedling, elongation, and heading stages, individual plants at the same developmental stage were selected for measurements with three biological and three technical replicates. From 10:00-11:00 am on the same day, after dark adaption by Dark Leaf Clip for 30 min, the value of F v/F m and Y(II) were measured with a photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 281 μmol m-2s-1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The response of photosynthetic fluorescence parameters to light intensity changes was determined using rapid light curves. Imaging Win software (Heinz Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) was used to collect and analyze fluorescence parameter data. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Microsoft Excel software.

Additional files

Primers used for RT-qPCR. Table S2. Percentage of chloroplasts containing different numbers of starch granules. (DOCX 19 kb)

Validation of sub-genome-specific RT-qPCR primers using Chinese Spring nullisomic-tetrasomic lines. CS: Chinese Spring; N1DT1B, N1AT1B, N1AT1D, and N1BT1D: Chinese Spring nullisomic-tetrasomic lines; J411: wild type; s4b-qD: TaSSIVb-D-specific primers; s4b-qA: TaSSIVb-A-specific primers; s4b-qB: TaSSIVb-B-specific primers. (DOCX 1759 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Xianchun Xia, Institute of Crop Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, for kindly providing us with the nullisomic-tetrasomic lines.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0102101 and 2016YFD0102106) and NSFC project (31100610) of P. R. China. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publishied article and its supplementary information files. The raw data are available from the cooresponding author on resonable request.

Authors’ contributions

HG and ZY developed the TILLING population and wrote the manuscript. XL screened the alleles. YL and XL designed the specific primers. YL carried out the RT-qPCR and microscopy analysis. HG and YL measured chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and prepared the drafting manuscript. YX and HX prepared figures. LZ, JG and SZ managed plant materials. LL conceived the original research, supervised data generation and analyses and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final muanuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Wheat samples have been used in the article, and seeds of the wild type were deposited in Institute of Crop Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The mutants were developed by the authors. All plants were grown and conducted in accordance with the local legislation. No voucher specimen was deposited in public herbarium.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AGPase

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylases

- DBE

Starch debranching enzymes

- EMS

Ethyl methanesulphonate

- ETR

Electron transport rate

- GBSS

Granule-bound starch synthase

- gpc

Grain protein content

- GT-1

Glycosyltranferase domain

- GT-5

Starch catalytic domain

- PAR

Photosynthetically active radiation

- PARSESNP

Project aligned related sequences and evaluate SNPs

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

- SBE

Starch branching enzymes

- SIFT

Sorting intolerant from tolerant

- SPSS

Statistical package for the social sciences

- SS

Starch synthases

- SSD

Single-seed descent

- SSIV

Starch synthesis IV

- TILLING

Targeting induced local lesions in genomes

- WT

Wild type

- Y(II)

Yield of PSII

Contributor Information

Huijun Guo, Email: guohuijun@caas.cn.

Yunchuan Liu, Email: liuyunchuan@caas.cn.

Xiao Li, Email: lixiao@caas.cn.

Zhihui Yan, Email: yanzhihui@caas.cn.

Yongdun Xie, Email: xieyongdun@caas.cn.

Hongchun Xiong, Email: xionghongchun@caas.cn.

Linshu Zhao, Email: zhaolinshu@caas.cn.

Jiayu Gu, Email: gujiayu@caas.cn.

Shirong Zhao, Email: zhaoshirong@caas.cn.

Luxiang Liu, Phone: 86-10-62122719, Email: liuluxiang@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Nakamura Y. Starch. 2015. pp. 211–237. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang G, Liu G, Peng X, Wei L, Wang C, Zhu Y, Ma Y, Jiang Y, Guo T. Increasing the starch content and grain weight of common wheat by overexpression of the cytosolic AGPase large subunit gene. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;73:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li N, Zhang S, Zhao Y, Li B, Zhang J. Over-expression of AGPase genes enhances seed weight and starch content in transgenic maize. Planta. 2011;233(2):241–250. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smidansky ED, Clancy M, Meyer FD, Lanning SP, Blake NK, Talbert LE, Giroux MJ. Enhanced ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase activity in wheat endosperm increases seed yield. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(3):1724–1729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022635299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagai YS, Sakulsingharoj C, Edwards GE, Satoh H, Greene TW, Blakeslee B, Okita TW. Control of starch synthesis in cereals: metabolite analysis of transgenic rice expressing an up-regulated cytoplasmic ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in developing seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50(3):635–643. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura T, Vrinten P, Hayakawa K, Ikeda J. Characterization of a granule-bound starch synthase isoform found in the pericarp of wheat. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:451–459. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vrinten P, Nakamura T. Wheat granule-bound starch synthase I and II are encoded by separate genes that are expressed in different tissues. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:255–264. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards A, Borthakur A, Bornemann S, Venail J, Denyer K, Waite D, Fulton D, Smith A, Martin C. Specificity of starch synthase isoforms from potato. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:724–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahaji A, Li J, Sanchez-Lopez AM, Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Ovecka M, Almagro G, Montero M, Ezquer I, Etxeberria E, et al. Starch biosynthesis, its regulation and biotechnological approaches to improve crop yields. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(1):87–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Yu G, Wei B, Wang Y, Zhang J, Hu Y, Liu Y, Yu G, Zhang H, Huang Y. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of a novel starch synthase in maize. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1013. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo J, Ahmed R, Kosar-Hashemi B, Larroque O, Butardo VM, Jr, Tanner GJ, Colgrave ML, Upadhyaya NM, Tetlow IJ, Emes MJ, et al. The different effects of starch synthase IIa mutations or variation on endosperm amylose content of barley, wheat and rice are determined by the distribution of starch synthase I and starch branching enzyme IIb between the starch granule and amyloplast stroma. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128(7):1407–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00122-015-2515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirose T, Terao T. A comprehensive expression analysis of the starch synthase gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Planta. 2004;220(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kossmann J, Abel GJW, Springer F, Lloyd JR, Willmitzer L. Cloning and functional analysis of a cDNA encoding a starch synthase from potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) that is predominantly expressed in leaf tissue. Planta. 1999;208:503–511. doi: 10.1007/s004250050587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dian W, Jiang H, Wu P. Evolution and expression analysis of starch synthase III and IV in rice. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(412):623–632. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harn C, Knight M, Ramakrishnan A, Guan H, Keeling PL, Wasserman BP. Isolation and characterization of the zSSIIa and zSSIIb starch synthase cDNA clones from maize endosperm. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:639–649. doi: 10.1023/A:1006079009072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang H, Dian W, Liu F, Wu P. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of three genes encoding starch synthase II in rice. Planta. 2004;218(6):1062–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Myers AM, James MG. Mutations affecting starch synthase III in Arabidopsis alter leaf starch structure and increase the rate of starch synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138(2):663–674. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roldan I, Wattebled F, Mercedes Lucas M, Delvalle D, Planchot V, Jimenez S, Perez R, Ball S, D’Hulst C, Merida A. The phenotype of soluble starch synthase IV defective mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests a novel function of elongation enzymes in the control of starch granule formation. Plant J. 2007;49(3):492–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szydlowski N, Ragel P, Raynaud S, Lucas MM, Roldan I, Montero M, Munoz FJ, Ovecka M, Bahaji A, Planchot V, et al. Starch granule initiation in Arabidopsis requires the presence of either class IV or class III starch synthases. Plant Cell. 2009;21(8):2443–2457. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamez-Arjona FM, Li J, Raynaud S, Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Ovecka M, Ragel P, Bahaji A, Pozueta-Romero J, Merida A. Enhancing the expression of starch synthase class IV results in increased levels of both transitory and long-term storage starch. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9(9):1049–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crumpton-Taylor M, Pike M, Lu KJ, Hylton CM, Feil R, Eicke S, Lunn JE, Zeeman SC, Smith AM. Starch synthase 4 is essential for coordination of starch granule formation with chloroplast division during Arabidopsis leaf expansion. New Phytol. 2013;200(4):1064–1075. doi: 10.1111/nph.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohdan T, Francisco PB, Jr, Sawada T, Hirose T, Terao T, Satoh H, Nakamura Y. Expression profiling of genes involved in starch synthesis in sink and source organs of rice. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(422):3229–3244. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toyosawa Y, Kawagoe Y, Matsushima R, Crofts N, Ogawa M, Fukuda M, Kumamaru T, Okazaki Y, Kusano M, Saito K, et al. Deficiency of starch synthase IIIa and IVb alters starch granule morphology from polyhedral to spherical in rice endosperm. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:1255–1270. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leterrier M, Holappa LD, Broglie KE, Beckles DM. Cloning, characterisation and comparative analysis of a starch synthase IV gene in wheat: functional and evolutionary implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra A, Singh A, Sharma M, Kumar P, Roy J. Development of EMS-induced mutation population for amylose and resistant starch variation in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) and identification of candidate genes responsible for amylose variation. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0896-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh A, Kumar P, Sharma M, Tuli R, Dhaliwal HS, Chaudhury A, Pal D, Roy J. Expression patterns of genes involved in starch biosynthesis during seed development in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) Mol Breed. 2015;35(9):184. doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0371-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Huang L, Min D, Phillips A, Wang S, Madgwick PJ, Parry MAJ, Hu Y-G. Development and characterization of a new TILLING population of common bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) PLoS One. 2012;7:e41570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen A, Jorge D. Wheat TILLING mutants show that the vernalization gene VRN1 down-regulates the flowering repressor VRN2 in leaves but is not essential for flowering. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(12):e1003134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald TL, Kazan K, Li Z, Morell MK, Manners JM. A high-throughput method for the detection of homologous gene deletions in hexaploid wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:264. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, Abernathy B, Zeng Y, Ozias-Akins P. TILLING by sequencing to identify induced mutations in stress resistance genes of peanut (Arachis hypogaea) BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1348-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCallum CM, Comai L, Greene EA, Henikoff S. Targeting Induced Local Lesions IN Genomes (TILLING) for plant functional genomics. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:439–442. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parry MAJ, Madgwick PJ, Bayon C, Tearall K, Hernandez-Lopez A, Baudo M, Rakszegi M, Hamada W, Al-Yassin A, Ouabbou H, et al. Mutation discovery for crop improvement. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(10):2817–2825. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Till BJ, Cooper J, Tai TH, Colowit P, Greene EA, Henikoff S, Comai L. Discovery of chemically induced mutations in rice by TILLING. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Till BJ, Reynolds SH, Greene EA, Codomo CA, Enns LC, Johnson JE, Burtner C, Odden AR, Young K, Taylor NE, et al. Large-scale discovery of induced point mutations with high-throughput TILLING (Arabidopsis) Genome Res. 2003;13:524–530. doi: 10.1101/gr.977903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong C, Vincent K, Sharp P. Simultaneous mutation detection of three homoeologous genes in wheat by High Resolution Melting analysis and Mutation Surveyor. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uauy C, Paraiso F, Colasuonno P, Tran RK, Tsai H, Berardi S, Comai L, Dubcovsky J. A modified TILLING approach to detect induced mutations in tetraploid and hexaploid wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slade AJ, Fuerstenberg SI, Loeffler D, Steine MN, Facciotti D. A reverse genetic, nontransgenic approach to wheat crop improvement by TILLING. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(1):75–81. doi: 10.1038/nbt1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hazard B, Zhang X, Colasuonno P, Uauy C, Beckles DM, Dubcovsky J. Induced mutations in the starch branching enzyme II (SBEII) genes increase amylose and resistant starch content in durum wheat. Crop Sci. 2012;52:1754–1766. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2012.02.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bovina R, Brunazzi A, Gasparini G, Sestili F, Palombieri S, Botticella E, Lafiandra D, Mantovani P, Massi A. Development of a TILLING resource in durum wheat for reverse- and forward-genetic analyses. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014;65:112–124. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sestili F, Palombieri S, Botticella E, Mantovani P, Bovina R, Lafiandra D. TILLING mutants of durum wheat result in a high amylose phenotype and provide information on alternative splicing mechanisms. Plant Sci. 2015;233:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slade AJ, McGuire C, Loeffler D, Mullenberg J, Skinner W, Fazio G, Holm A, Brandt KM, Steine MN, Goodstal JF, et al. Development of high amylose wheat through TILLING. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazard B, Zhang X, Colasuonno P, Uauy C, Beckles DM, Dubcovsky J. Induced Mutations in the Starch Branching Enzyme II (SBEII) genes increase amylose and resistant starch content in durum wheat. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimbata T, Ai Y, Fujita M, Inokuma T, Vrinten P, Sunohara A, Saito M, Takiya T, Jane JL, Nakamura T. Effects of homoeologous wheat starch synthase IIa genes on starch properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(48):12004–12010. doi: 10.1021/jf303623e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahuja G, Jaiswal S, Hucl P, Chibbar RN. Genome-specific granule-bound starch synthase I (GBSSI) influences starch biochemical and functional characteristics in near-isogenic wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) lines. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(49):12129–12138. doi: 10.1021/jf4040767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wickramasinghe HAM, Miura H. Gene dosage effect of the wheat Wx alleles and their interaction on amylose synthesis in the endosperm. Euphytica. 2003;132:303–310. doi: 10.1023/A:1025098707390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Botticella E, Sestili F, Hernandez-Lopez A, Phillips A, Lafiandra D. High resolution melting analysis for the detection of EMS induced mutations in wheat SBEIIa genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crumpton-Taylor M, Grandison S, Png KM, Bushby AJ, Smith AM. Control of starch granule numbers in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(2):905–916. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogg AC, Gause K, Hofer P, Martin JM, Graybosch RA, Hansen LE, Giroux MJ. Creation of a high-amylose durum wheat through mutagenesis of starch synthase II (SSIIa) J Cereal Sci. 2013;57(3):377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2013.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konik-Rose C, Thistleton J, Chanvrier H, Tan I, Halley P, Gidley M, Kosar-Hashemi B, Wang H, Larroque O, Ikea J, et al. Effects of starch synthase IIa gene dosage on grain, protein and starch in endosperm of wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;115(8):1053–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0631-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avni R, Zhao R, Pearce S, Jun Y, Uauy C, Tabbita F, Fahima T, Slade A, Dubcovsky J, Distelfeld A. Functional characterization of GPC-1 genes in hexaploid wheat. Planta. 2014;239(2):313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1977-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ludewig F, Sonnewald U, Kauder F, Heineke D, Geiger M, Stitt M, Muller-Rober BT, Gillissen B, Kuhn C, Frommer WB. The role of transient starch in acclimation to elevated atmospheric CO2. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:147–151. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00580-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldschmidt EE, Huber SC. Regulation of photosynthesis by end-product accumulation in leaves of plants storing starch, sucrose, and hexose sugars. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1443–1448. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ragel P, Streb S, Feil R, Sahrawy M, Annunziata MG, Lunn JE, Zeeman S, Merida A. Loss of starch granule initiation has a deleterious effect on the growth of arabidopsis plants due to an accumulation of ADP-glucose. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(1):75–85. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.223420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Till BJ, Zerr T, Comai L, Henikoff S. A protocol for TILLING and Ecotilling in plants and animals. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(5):2465–2477. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor NE, Greene EA. PARSESNP: a tool for the analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3808–3811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu J, Wang Q, Cui M, Han B, Guo H, Zhao L, Xie Y, Song X, Liu L. Cloning and characterization of Ku70 and Ku80 homologues involved in DNA repair process in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Genet Resourc. 2014;12(S1):S99–S103. doi: 10.1017/S1479262114000367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo H-j, Zhao H-b, Zhao L-s, Gu J-y, Zhao S-r, Li J-h, Liu Q-c, Liu L-x. Characterization of a novel chlorophyll-deficient mutant Mt6172 in wheat. J Integr Agric. 2012;11(6):888–97.

- 59.Xiong H, Guo H, Xie Y, Zhao L, Gu J, Zhao S, Li J, Liu L. Enhancement of dwarf wheat germplasm with high-yield potential derived from induced mutagenesis. Plant Genet Resourc. 2016. doi:10.1017/S1479262116000459.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primers used for RT-qPCR. Table S2. Percentage of chloroplasts containing different numbers of starch granules. (DOCX 19 kb)

Validation of sub-genome-specific RT-qPCR primers using Chinese Spring nullisomic-tetrasomic lines. CS: Chinese Spring; N1DT1B, N1AT1B, N1AT1D, and N1BT1D: Chinese Spring nullisomic-tetrasomic lines; J411: wild type; s4b-qD: TaSSIVb-D-specific primers; s4b-qA: TaSSIVb-A-specific primers; s4b-qB: TaSSIVb-B-specific primers. (DOCX 1759 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this publishied article and its supplementary information files. The raw data are available from the cooresponding author on resonable request.