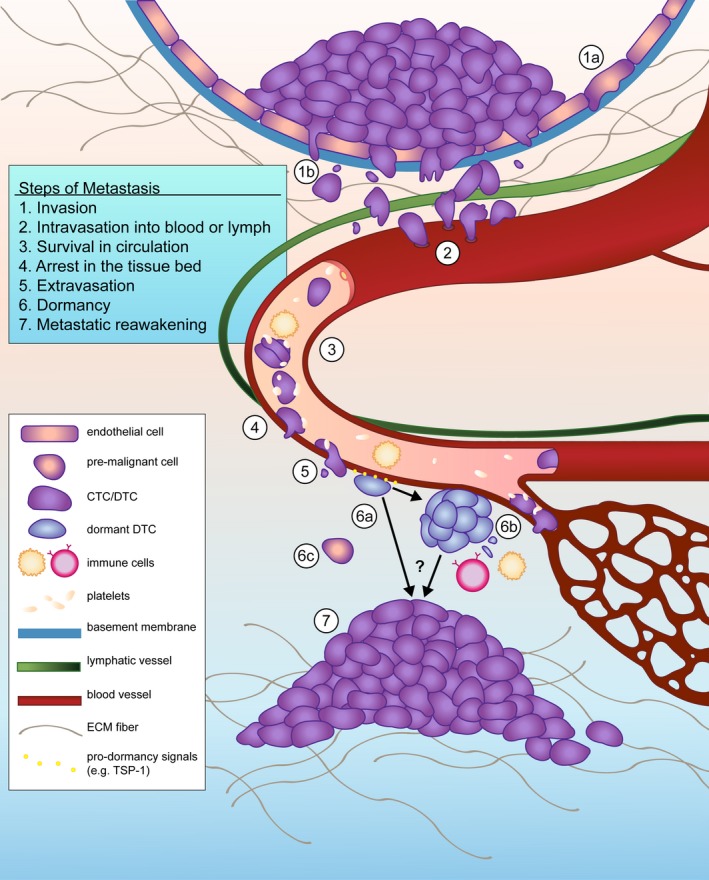

Figure 1.

Tumor cell dissemination enables the spread of cancer from its site of origin. Local invasion through the basement membrane of a duct and ECM fibers may occur early (1a) or later (1b) in malignant progression. Upon reaching a local or intratumoral vessel conduit, DTCs intravasate into hematogenous or lymphatic vessels (2). Blood is a hostile environment and CTCs must contend with circulating immune cells, loss of cell–cell junctions, and shear stress to survive (3). Platelets offset these hurdles by providing a protective coat that promotes the formation of tumor microemboli and arrest on the luminal side of capillaries and venules (4). As DTCs extravasate (5), they encounter a foreign microenvironment containing new obstacles to survival. Some DTCs enter dormancy during this stressful transition, a process in which microenvironmental factors such as TSP‐1, BMP‐4, and BMP‐7 have been implicated. Single dormant cells that undergo cell cycle arrest have been observed in the perivascular niche (6a), where they apparently avoid immunodetection. Small DTC clusters and micrometastases may continue to divide, but are prevented from crossing a size threshold due to angiogenic limitations or immunosurveillance (6b). The contribution of early disseminators, which may or may not have ever entered a completely malignant state, is unknown (6c). The mechanisms through which dormant DTCs eventually reawaken are currently being elucidated (7) and likely include tissue‐specific factors, molecules derived from angiogenic neovessels, and other unknown effectors.