Abstract

The use of bacteria for cancer therapy, which was proposed many years ago, was not recognized as a potential therapeutic strategy until recently. Technological advances and updated knowledge have enabled the genetic engineering of bacteria for their safe and effective application in the treatment of cancer. The efficacy of radiotherapy depends mainly on tissue oxygen levels, and low oxygen concentrations in necrotic and hypoxic regions are a common cause of treatment failure. In addition, the distribution of a drug is important for the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy, and the poor vasculature in tumors impairs drug delivery, limiting the efficacy of a drug, especially in necrotic and hypoxic regions. Bacteria-mediated cancer therapy (BMCT) relies on facultative anaerobes that can survive in well or poorly oxygenated regions, and it therefore improves the therapeutic efficacy drug distribution throughout the tumor mass. Since the mid-1990s, the number of published bacterial therapy papers has increased rapidly, with a doubling time of 2.5 years in which the use of Salmonella increased significantly. BMCT is being reevaluated to overcome some of the drawbacks of conventional therapies. This review focuses on Salmonella-mediated cancer therapy as the most widely used type of BMCT.2.

Keywords: Bacteria-mediated cancer therapy (BMCT), Salmonella typhimurium, Cancer, Molecular imaging, Targeting, Immune system

History of Bacteria-Mediated Cancer Therapy

In 1891, William B. Coley, a bone sarcoma surgeon, injected streptococcal organisms into a patient with inoperable cancer and successfully cured the patient [1]. Over the next 40 years, as head of the Bone Tumor Service at Memorial Hospital in New York, Coley applied his therapy with bacteria or bacterial products, which became known as Coley’s toxin, to over 1000 cancer patients [2]. Coley believed that his toxin, based on the use of a streptococcal organism causing erysipelas, could stimulate a cancer patient’s immune system to attack the tumors; however, his work came under criticism because of several inconsistencies: (1) his patient follow-up was poorly controlled and poorly documented; (2) there were 13 different toxin preparations, and some of these were more effective than others; (3) Coley used various methods of administration. Some toxins were given intravenously, others intramuscularly, and some were injected directly into the tumor. In addition, the lack of modern techniques and modalities to accurately diagnose cancer and quantify changes in immune responses resulted in a poor understanding of the underlying mechanisms and difficulties explaining his results.

The use of Coley’s toxin for cancer treatment was banned after 1962 after failing to obtain FDA approval. Currently, orthopedic oncologists do not use Coley’s toxins for the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Most cancer patients are currently treated with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy; however, the limited efficacy of these modern therapies in hypoxic regions of tumors remains unresolved [3]. Bacteriotherapy is one of several modern therapies currently being considered as an alternative novel therapy.

BMCT Can Overcome Some of the Drawbacks of Traditional Cancer Therapy

Surgery is the most common cancer treatment, and it has been used for many years. However, surgery is not an effective therapy for metastatic disease, which requires combination treatments with other traditional therapies such as radiation or chemotherapy. These therapies have many drawbacks that could lead to the incomplete removal of cancer cells and potential recurrence.

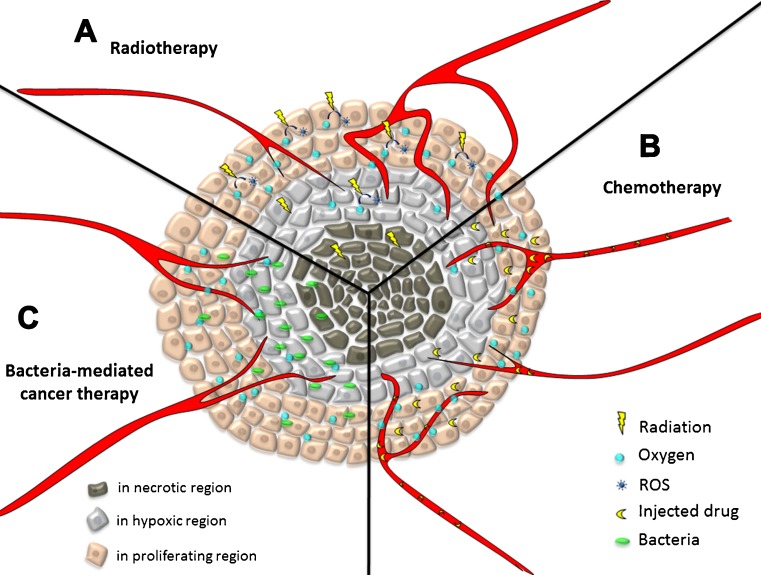

Radiotherapy for cancer treatment is based on the use of ionizing radiation to kill cells by causing DNA damage, particularly DNA double strand breaks (Fig. 1a). This damage results from ionizations in or very close to the DNA that produce a radical on the DNA (DNA⋅). This radical then enters into a competition for oxidation, primarily by oxygen (which makes the damage permanent), or reduction, primarily by –SH-containing compounds that can restore the DNA to its original form. Therefore, DNA damage is reduced in the absence of oxygen. Clinical trials have demonstrated that markedly hypoxic tumors [typically those with a median pO2 (oxygen partial pressure) of less than 10 mmHg] are more radio-resistant than less hypoxic tumors.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of different cancer therapies. a Radiotherapy: DNA damage is decreased in the absence of oxygen. b Chemotherapy: distance from blood vessels and the resistance of hypoxic cells to many anticancer agents are current obstacles. c Bacteria-mediated cancer therapy: independent proliferation and abundant distribution in the tumor mass are among the advantages discussed in this review

In chemotherapy, hypoxia limits the efficacy of treatment because it increases the resistance of cells to anticancer drugs (Fig. 1b) for several reasons, as follows:

Increased distance from blood vessels results in inadequate exposure to certain types of anticancer drugs.

Hypoxic conditions facilitate the selection of cancer cells that have lost sensitivity to p53-mediated apoptosis. In addition, hypoxia induces the expression of genes involved in drug resistance, especially genes encoding P-glycoprotein. Therefore, hypoxic cells become unresponsive to many anticancer agents.

The action of some anticancer agents (e.g., bleomycin) resembles that of radiation in that oxygen increases the cytotoxicity of the DNA lesions caused by the treatment. Therefore, the efficacy of treatment in target cells is reduced by the low oxygen concentration in hypoxic regions.

The use of bacteria for cancer therapy has many advantages over the traditional cancer therapies described above (Table 1). The amount of bacterial accumulation in tumors is approximately 1000 times higher than that in normal organs [40]. The proliferative capacity of bacteria extends their therapeutic effect without the need for external supply (Fig. 1c). The fully sequenced genomes of many bacteria enable genomic manipulation to improve their safety in humans and enhance their tumor killing effect. Among bacteria used for cancer treatment, Salmonella is highly regarded because of its tumor-specific localization, its ability to target various types of tumors, a fully sequenced genome, and its natural toxicity [40]. In addition, Salmonella is a facultative strain that can colonize small metastases in addition to large solid tumors. In a recent review, bacteria were described as tiny programmable ‘robot factories’ [41], with their flagella as propellers, chemotactic receptors as sensors, and reporter proteins as signal emitter chips that can be used to engineer these bacteria as needed. With the help of modern technology and extensive studies on gene regulation, protein interactions, and oncology, the ideal bacteria for cancer therapy are being optimized and upgraded intensively.

Table 1.

Advantages of using BMCT

| Advantages | Detail | References |

|---|---|---|

| Various administration routes | Intravenous | [4–18] |

| Intraperitoneal | [19–23] | |

| Intratumoral | [19, 24–27] | |

| Oral | [17, 28, 29] | |

| Broad tumor-targeting ability | Colon | [7, 9, 10, 14, 19, 24, 30, 31] |

| Fibrosarcoma | [17] | |

| Bladder | [13] | |

| Liver | [6, 7, 15, 30] | |

| Pancreas | [8, 21] | |

| Lung | [14, 15] | |

| Melanoma | [18, 20, 22, 27, 28, 31, 32] | |

| Breast | [4, 11, 12, 16, 23, 25, 31] | |

| Prostate | [20, 26] | |

| Flexibility of delivery | Protein derived from eukaryotes | [5, 12, 20, 29] |

| Protein derived from prokaryotes | [7, 11, 30, 31] | |

| Enzyme-prodrug | [4, 13] | |

| DNA | [18, 19, 25] | |

| siRNA, shRNA | [9, 26, 28] | |

| Facilitating host’s immune responses | TAM reduction | [16] |

| Antigen delivery | [17, 23, 33] | |

| Upregulation of gap junction | [27] | |

| Shift from immune suppressive to immunogenic | [22, 24] | |

| Noninvasive monitoring | Luminescence | [6, 7, 14, 30, 31, 34–37] |

| Fluorescence | [8] | |

| MRI | [38] | |

| PET | [39] | |

| Can be combined with other therapies | Chemotherapy | [5, 13, 15, 32] |

| Radiation | [12, 21, 31] | |

| Viral therapy | [14] |

Delivery of Bacteria to Tumors

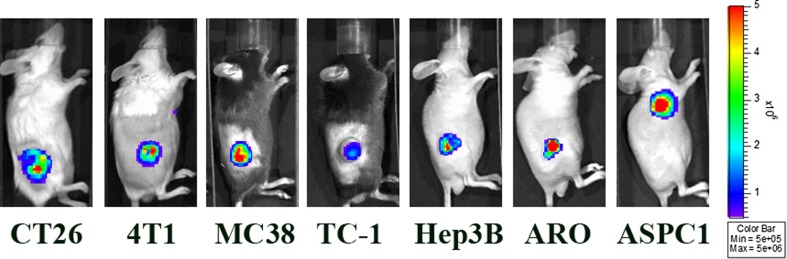

One key advantage of BMCT is the selective accumulation of bacteria in tumors rather than in normal organs (Fig. 2). The irregular vasculature of tumors results in the formation of hypoxic and necrotic areas [3] that are specific to tumors and do not form in most organs. This feature may explain how obligate anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium and Bifidobacterium are found in tumor masses but not in normal organs with oxygenic environments [4, 5, 42, 43].

Fig. 2.

Optical imaging showing lux-expressing Salmonella typhimurium defected in ppGpp synthesis (SalΔppGpp/lux) accumulated in various tumors after 3 days of intravenous injection. CT26: mouse colon carcinoma, 4 T1: mouse mammary carcinoma, MC38: murine colorectal adenocarcinoma, TC-1: mouse lung cancer, Hep3B: human hepatocellular carcinoma, ARO: human thyroid carcinoma, ASPC1: human pancreatic adenocarcinoma

However, compared to anaerobes, facultative anaerobes such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella have been researched more intensively for BMCT applications [41]. The culture and handling of facultative anaerobes are not restricted by oxygen conditions. These bacteria can target large as well as small tumors, whereas anaerobic bacteria are not suitable for the treatment of small tumors or metastases [44]. The tumor-targeting mechanism of facultative bacteria is complex and is the subject of debate. Generally, there are two opposing theories to explain this mechanism: (1) the chemotactic system and motility of bacteria mediate the successful bacterial colonization of tumors [45–47], and (2) a passive mechanism by which inflammatory cytokines are triggered after intravenous injection of bacteria leads to the dilation of tumor blood vessels, allowing the entry of bacteria [48, 49]. Work from our group using non-motile Salmonella with a mutation in the flhD gene showed that they accumulate in tumors to an extent comparable to that of motile bacteria (unpublished data). However, additional studies are needed to clarify this issue.

Tumors contain immune privileged environments [50] where bacteria can hide from clearance by macrophages and neutrophils [51]. This is another potential mechanism to explain how bacteria proliferate and survive for longer periods in tumor sites than in normal tissues.

In Vivo Monitoring of Bacteria with Molecular Imaging Technology

The most common way to image bacteria in small animal models is labeling them with luminenescence gene operon derived from a luminescent bacterial strain [6, 7, 30]. The bacterial luciferase (lux) operon encodes five gene clusters, lux C, D, A, B, and E. Lux A and B express bacterial luciferase enzyme, while lux C, D, and E control fatty aldehyde enzyme complex production, which synthesizes the substrates. Because lux operon encodes all proteins necessary for light production, including luciferase, substrate, and substrate-regenerating enzymes, bacteria expressing lux operon require only oxygen and do not require any other exogenous substrate to produce bioluminescence [34, 35]. The advantage of bioluminescence is its minimal background noise, since luciferase is not a natural constituent of mammalian organisms. Bioluminescence-based approaches currently lack detailed tomographic information and are limited to relatively small animals [34, 52–54]. Besides, fluorescence labeling is also used in some studies [8, 55]. Fluorescence imaging uses a fluorescent protein, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP), that is excited with external illumination, and the emission is subsequently detected [56]. GFP encoding cDNA can easily be included in the myriad therapeutic vectors and serve as a monitoring tool for gene therapy. Nevertheless, excitation and emission wavelengths in the range of 500 nm (e.g., GFP) have limited penetration in mammalian tissues (1–5 mm). Since mammalian tissues absorb light that is used to excite these fluors, the tissues also fluoresce when excited at these wavelengths. The combination of absorption of specific signal and autofluorescence of tissues can result in a poor signal-to-noise ratio [57]. Recently, red-shifted fluorescence protein (RFP) has been shown to have an advantage over GFP in that red light penetrates tissues more efficiently than green [58]. A newer approach to fluorescence imaging of deeper structures uses fluorescence-mediated tomography (FMT) [59]. The subject is exposed to continuous wave or pulsed light from different sources in an imaging chamber, and detectors arranged in a spatially defined order capture the emitted light. Mathematical processing of this information results in a reconstructed tomographic image.

Optical imaging techniques such as luminescence or fluorescence are limited in approaching to bigger models or clinical trials. Interestingly, PET imaging showed the possibility to monitor Salmonellae expressing the herpes simplex thymidine kinase (HSV1-tk) reporter gene [55]. The bacterial targeting and replication can be imaged in vivo in tumors with a radiolabeled 2′-fluoro-1-beta-d-arabino-furanosyl-5-iodo-uracil (FIAU), which is selectively phosphorylated and trapped in bacteria expressing HSV1-TK. Another study tried to overexpress bacterial ferritin in Escherichia coli to achieve imaging of bacterial colonization in tumors by MRI [38]. These studies using PET or MRI imaging to monitor bacteria in vivo would be needed in the future when bacteria are applied in bigger models or humans.

Recently, an interesting study was reported using probiotic bacteria to diagnose cancer in urine [60]. Genetically engineered Escherichia coli Nissle was developed for oral administration for diagnosing the presence of liver metastasis by producing easily detectable signals in urine. Exploiting the tumor-colonization ability of bacteria to detected tumors indirectly is an attractive idea that can be considered as a primary screening for tumor existence before going to more complicated technology such as PET or SPECT imaging.

Cancer Treatment Strategies Based on the Use of Bacteria

In the nineteenth century, Coley used streptococcal organisms or bacterial products for the treatment of patients with inoperable cancer [1]. Currently, many virulent bacteria used for cancer therapy are attenuated using different gene depletion strategies to ensure their safety. In our laboratory we attenuated S. typhimurium by deleting two genes, relA and SpoT. Na et al. [61] found that relA and spoT double mutant Salmonella, which is defective in ppGpp synthesis (ΔppGpp strain), was virtually avirulent in Balb/c mice. For LD50 values with the ΔppGpp mutant, the LD50 was ∼ 105 higher than that of the wild type after oral or intraperitoneal inoculation. VNP20009 is also a common attenuated strain used in BMCT, which was mutated purI and msbB genes. The purI deletion limits bacterial growth in areas that have substantial cell turnover, death, and cellular debris as the sources for external adenine, while the deletion of the msbB gene, which is required for synthesis of lipid A, helps to reduce the toxicity associated with induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a) [62]. Another way to attenuate S. typhimurium was done by generating a Salmonella A1 strain. First, the bacteria were randomly mutated by nitrosoguanidine treatment. Second, the auxotrophs were selected and their virulence and toxicity tested in tumor cells in vitro or in nude mice, respectively. Finally, the well-tumor targeted strain (named A1R) was re-isolated from tumor-bearing mouse models [55].

Although some of these organisms are used as monotherapy [6, 8, 24], most of them are used as vehicles to deliver therapeutic agents such as DNA [19], siRNA [9, 28], toxins [7, 10–12, 20, 30], and prodrug-enzymes [13], or combined with other therapies [14, 15, 21, 32] to enhance their therapeutic effect.

-

Delivery of DNA or siRNA

Listeria monocytogenes is a good candidate for the delivery of DNA to mammalian cells because of its natural ability to invade the cell, lyse the phagosomal vacuole of infected cells, proliferate in the host cell cytoplasm, and actively enter adjacent cells. Tangney et al. used an ampicillin-sensitive strain to create a system that could deliver DNA to infected cancer cells [25]. In this system, L. monocytogenes is lysed within the tumor after the administration of ampicillin to release plasmids inside the cells. Plasmids encoding firefly luciferase under the control of the CMV promoter are then taken up, and the gene is expressed by host cells. This study demonstrated the possibility of using bacteria to deliver therapeutic genes to cancer cells in vivo specifically, economically, and effectively.

Critchley et al. reported a system based on the use of the inv gene from Yersinia and listeriolysin O from Listeria to convert E. coli into an invasive strain [63]. Binding of invasin to b1-integrin promotes phagocytosis of the bacteria. After internalization, listeriolysin O can gain access to the phagosomal membrane because of its pore-forming ability, and the cytoplasmic contents of the bacteria can be released into the cytoplasmic compartment of mammalian cells. The authors used this strategy to demonstrate the potential use of E. coli as a delivery vector for genes or therapeutic proteins.

The use of invasive Salmonella species to deliver RNA interference (RNAi) has been reported. S. typhimurium expressing plasmid-based Stat3-specific siRNAs significantly inhibited tumor growth, reduced the number of metastastic organs, and prolonged the life span of prostate tumor-bearing C57BL6 mice compared to bacterial treatment alone [26]. A different group showed that oral administration of S. typhimurium carrying shRNA-expressing vectors targeting bcl2 induced significant gene silencing in murine melanoma cells, remarkably delaying tumor growth and prolonging survival in a mouse model [28].

Gene transfer using bacteria could become a promising strategy for the treatment of cancer, although further studies are necessary to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

-

Delivery of engineered toxins or pro-drugs

Because bacteria have their own protein-synthesizing machinery, a potential strategy would be to induce them to synthesize therapeutic proteins and deliver them to the tumor mass using their tumor-targeting ability.

Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily that can trigger apoptosis of tumor cells by binding to their membrane receptors (DR4 and DR5) and not to normal cells [64]. Hu et al. engineered a Bifidobacterium longum strain expressing the extracellular domain of TRAIL that showed inhibitory effects on tumor xenografts after intravenous injection [5]. Likewise, a non-pathogenic S. typhimurium was engineered to secrete murine TRAIL under the control of the prokaryotic radiation-inducible RecA promoter [12]. This system not only succeeded in generating TRAIL, but also enabled timed induction to improve the safety of the strategy.

Our group reported the expression of cytolysin A, a pore-forming toxin, in Salmonella [7] and E. coli [31]. For safety reasons, the expression of the toxin was tightly controlled by a pBAD expression system in which the promoter is induced by L-arabinose. Insertion of the lux gene in the bacterial chromosome allowed monitoring of the location of bacteria noninvasively and repeatedly. In this study, we reported a strategy that can remotely control the expression of a toxin gene in vivo by using the pBAD system combined with molecular imaging.

In another report, we used the mitochondrial targeting domain of Noxa (MTD), a transcriptional target of p53 that mediates apoptosis induction via activation of mitochondrial damage and the intrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway. A holin/lysine lysis phage system was deployed to deliver the toxin, and a novel cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) derived from a voltage-gated potassium channel (DS4.3) was conjugated to MTD for import into cancer cells [10].

Enzyme-prodrug therapy is being developed as a strategy in which the drug is only converted into an active form at the target site. This strategy was used to introduce E. coli nitroreductase, which activates the non-toxic prodrug CB 1954 to a toxic anticancer drug, into a strain of Clostridium beijerinckii [65]. Nitroreductase produced by these clostridia enhanced the killing of tumor cells in vitro and was detectable in all tumors during the first 5 days after intravenous injection of inactive clostridial spores. Likewise, Clostridium beijerinckii was genetically engineered to constitutively express an E. coli gene encoding cytosine deaminase [66] (CD), which increased the sensitivity of murine EMT6 carcinoma cells to 5-fluorocytosine by approximately 500-fold. In a different report, Fujimori et al. created a plasmid encoding the CD gene and used it to transform Bifidobacterium longum in a system termed Bifidobacterial Selective Targeting-Cytosine Deaminase therapy. In another enzyme-prodrug strategy, the Herpes Simplex Virus-Thymidine Kinase (HSV-TK) gene was transformed into Bifidobacterium infantis to create the Herpes Simplex Virus-Thymidine Kinase/Ganciclovir (HSV-TK/GCV) system [13]. Thymidine kinase expressed in bacteria that specifically colonize tumor tissues can convert the non-toxic precursor ganciclovir into ganciclovir-3-phosphate, a toxic substance that kills tumor cells.

-

Triggering immune responses

Established tumors can activate various strategies to escape the host immune surveillance system [50, 67]. Recent evidence suggests that BMCT sensitizes immune cells to recognize tumor cells and triggers their clearance. Weibel et al. reported that colonization of E. coli K12 in 4 T1 murine breast tumors could alter the tumor microenvironment [68]. The colonization caused the redistribution of hypoxic areas, enhancement of collagen IV deposition, redistribution of tumor-associated macrophages, formation of granulation tissue around bacterial colonies, and upregulated TNFα and matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression. These alterations led to a strong reduction of pulmonary metastatic events.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are found in abundance in various tumor tissues and are associated with poor prognosis [69]. Galmbacher et al. attempted to deplete TAMs in murine breast cancer using an attenuated Shigella flexneri [16]. The profound reduction of TAMs was accompanied by a strong tumor suppressive effect in 4 T1 breast cancer models.

Recently, a group reported that administration of Salmonella alters the phenotypic and functional maturation of intratumoral myeloid cells, converting them into a less suppressive type, hence enhancing the host’s anti-tumor responses [24].

-

Combination therapy

Despite the numerous advantages of BMCT compared with conventional therapies, the results are not fully satisfactory in many cases. Single therapy using bacteria is generally insufficient to completely block or significantly suppress tumor growth. Hence, many recent reports suggest that the combination of BMCT with other therapies would be more effective to treat tumors.

The combination of an angiogenesis inhibitor, endostatin, with a TRAIL-expressing Bifidobacterium could trigger a synergistic effect through two separate mechanisms: endostatin depresses vascularization and inhibits nutrient provision during tumor growth, while TRAIL induces apoptosis of tumor cells by binding to receptors and activating related apoptosis pathways [5]. In addition, a low dose of a chemotherapeutic drug, adriamycin, was enough to enhance the tumor-inhibiting effect when combined with this bacterial strain.

Combined treatment with radiation also shows an additive effect with BMCT. Platt et al. reported that the anti-tumor efficacy of lipid A mutant Salmonella is enhanced when combined with X-ray irradiation [70]. The authors proposed several explanations for these results as follows: (1) X-ray irradiation might help render some of the tumor cells more vulnerable to Salmonella infection and/or to Salmonella toxins; (2) X-rays might alter the tumor environment, rendering it more accessible to Salmonella infection; (3) X-rays might render tumor cells more vulnerable to attack by immune system cells recruited by Salmonella.

In work from our group, radiation therapy significantly enhanced tumor shrinkage and even induced the complete disappearance of tumors in CT26 tumor models with E. coli-expressing ClyA [31].

Controllable Gene Expression

To minimize the side effects of BMCT associated with the delivery of toxin genes to a tumor mass, a controllable gene expression system is necessary to modulate the timing and specificity of drug delivery. Variable promoters have been used for this purpose (Table 2). The pBAD system requires an external inducer, L-arabinose, to release AraC, as a repressor normally binds to this promoter and prevents transcription [76]. In our study, the pBAD promoter controlled toxin gene expression until the administration of L-arabinose by intravenous or intraperitoneal injection [7]. Deletion of the ara operon of Salmonella inhibited L-arabinose metabolism, leading to the activation of the pBAD promoter following induction [71].

Table 2.

Inducible gene expression controlling systems

Similarly, the pTet system is induced by external chemicals such as tetracycline or doxycycline, and a bidirectional promoter allows the simultaneous expression of two genes [77]. Jiang et al. inserted Renilla luciferase and ClyA genes on both sides of this promoter to simultaneously visualize the bacteria and deliver the toxin gene [30].

The RecA promoter requires γ-irradiation to trigger gene expression via DNA damage responses [78]. This strategy uses radiation for therapeutic as well as gene induction purposes. Ganai et al. showed synergistically delayed tumor growth in 4 T1 tumor-bearing mice treated with 2 Gy γ-irradiation at 48 h after injection of TRAIL-expressing bacteria under the control of the RecA promoter [12].

Quorum sensing-promoters are turned on when bacterial density increases. Anderson et al. inserted the inv gene downstream of the lux quorum system, which showed that invasiveness depended on the multiplicity of infection and was comparable to that of the constitutive construct [72]. A recent publication reported integration of the pBAD promoter into the quorum sensing system, which enabled bacteria to activate neighbors and increased the time scale of protein production [73].

Hypoxia, a common feature of most tumor tissues, leads to resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, this characteristic can be exploited by using hypoxia-inducible promoters to control toxin gene expression specifically. Mengesha et al. created a hypoxia-inducible promoter (HIP-1) from a portion of the endogenous Salmonella pepT promoter and showed gene expression under both acute and chronic hypoxic conditions, but not under normoxia [79]. In a different report, an FNA-responsive promoter was used to specifically deliver cytolysin to the tumor mass and to reduce side effects.

An Ideal Bug for the Future

In conclusion, BMCT is a promising candidate for future cancer therapy. However, additional studies are necessary to facilitate the “bench to bed” transition. The toxicity of bacteria, especially that of natural virulent bacteria such as Salmonella, Listeria, and Clostridium, is problematic. Late-stage cancer patients are mostly immunocompromised. Therefore, attenuating the toxicity of bacteria using gene-mutation strategies is necessary to ensure their stability and safety for clinical approval. For human applications, bacterial imaging using radioactive tracers rather than luminescent or fluorescent reporter genes should be considered. An ideal combination of bacteria with other traditional therapies could be effective for the elimination of tumors and metastasis. Overcoming these obstacles is important to move BMCT closer to clinical application in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Pioneer Research Center Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2015M3C1A3056410). Nguyen V.H. was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014M3A9B5073747).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Vu Hong Nguyen and Jung-Joon Min declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Chonnam National University Animal Research Committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All subjects in the study gave written informed consent.

References

- 1.Coley WB. Contribution to the knowledge of sarcoma. Ann Surg. 1891;14:199–220. doi: 10.1097/00000658-189112000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy EF. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop J. 2006;26:154–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JM, Wilson WR. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:437–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujimori M. Genetically engineered Bifidobacterium as a drug delivery system for systemic therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer. 2006;13:27–31. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.13.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu B, Kou L, Li C, Zhu LP, Fan YR, Wu ZW, et al. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system of TRAIL and endostatin cooperates with chemotherapeutic drugs to inhibit hypoxic tumor growth. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:655–63. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li B, He H, Zhang S, Zhao W, Li N, Shao R. Salmonella typhimurium strain SL7207 induces apoptosis and inhibits the growth of HepG2 hepatoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2012;2:562–68. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2012.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen VH, Kim HS, Ha JM, Hong YJ, Choy HE, Min JJ. Genetically engineered Salmonella typhimurium as an imageable therapeutic probe for cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:18–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao M, Geller J, Ma H, Yang M, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Monotherapy with a tumor-targeting mutant of Salmonella typhimurium cures orthotopic metastatic mouse models of human prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10170–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703867104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo H, Zhang J, Inal C, Nguyen T, Fruehauf JH, Keates AC, et al. Targeting tumor gene by shRNA-expressing Salmonella -mediated RNAi. Gene Ther. 2011;18:95–105. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong JH, Kim K, Lim D, Jeong K, Hong Y, Nguyen VH, et al. Anti-tumoral effect of the mitochondrial target domain of Noxa delivered by an engineered Salmonella typhimurium. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e80050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan RM, Green J, Williams PJ, Tazzyman S, Hunt S, Harmey JH, et al. Bacterial delivery of a novel cytolysin to hypoxic areas of solid tumors. Gene Ther. 2009;16:329–39. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganai S, Arenas RB, Forbes NS. Tumour-targeted delivery of TRAIL using Salmonella typhimurium enhances breast cancer survival in mice. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1683–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang W, He Y, Zhou S, Ma Y, Liu G. A novel Bifidobacterium infantis-mediated TK/GCV suicide gene therapy system exhibits antitumor activity in a rat model of bladder cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:155. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin M, Le Boeuf F, Murphy C, Roy DG, Falls T, Bell JC, et al. Bacterial-mediated knockdown of tumor resistance to an oncolytic virus enhances therapy. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1188–97. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CH, Wu CL, Tai YS, Shiau AL. Systemic administration of attenuated Salmonella choleraesuis in combination with cisplatin for cancer therapy. Mol Ther. 2005;11:707–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galmbacher K, Heisig M, Hotz C, Wischhusen J, Galmiche A, Bergmann B, et al. Shigella mediated depletion of macrophages in a murine breast cancer model is associated with tumor regression. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roider E, Jellbauer S, Köhn B, Berchtold C, Partilla M, Busch D, et al. Invasion and destruction of a murine fibrosarcoma by Salmonella-induced effector CD8 T cells as a therapeutic intervention against cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:371–80. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0950-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CH, Wu CL, Shiau AL. Systemic administration of attenuated Salmonella choleraesuis carrying thrombospondin-1 gene leads to tumor-specific transgene expression, delayed tumor growth and prolonged survival in the murine melanoma model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;12:175–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne WL, Murphy CT, Cronin M, Wirth T, Tangney M. Bacterial-mediated DNA delivery to tumour associated phagocytic cells. J Control Release. 2014;196:384–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Yang B, Cheng X, Qiao Y, Tang B, Chen G, et al. Salmonella-mediated tumor-targeting TRAIL gene therapy significantly suppresses melanoma growth in mouse model. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:325–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quispe-Tintaya W, Chandra D, Jahangir A, Harris M, Casadevall A, Dadachova E, et al. Nontoxic radioactive Listeria at is a highly effective therapy against metastatic pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8668–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211287110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaimala S, Mohamed Y, Nader N, Issac J, Elkord E, Chouaib S, et al. Salmonella-mediated tumor regression involves targeting of tumor myeloid suppressor cells causing a shift to M1-like phenotype and reduction in suppressive capacity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:587–99. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1543-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SH, Castro F, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. High efficacy of a listeria-based vaccine against metastatic breast cancer reveals a dual mode of action. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5860–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong EH, Chang SY, Lee BR, Pyun AR, Kim JW, Kweon MN, et al. Intratumoral injection of attenuated Salmonella vaccine can induce tumor microenvironmental shift from immune suppressive to immunogenic. Vaccine. 2013;31:1377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tangney M, van Pijkeren J, Gahan C. The use of Listeria monocytogenes as a DNA delivery vector for cancer gene therapy. Bioeng Bugs. 2010;1:284–7. doi: 10.4161/bbug.1.4.11725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Gao L, Zhao L, Guo B, Ji K, Tian Y, et al. Intratumoral delivery and suppression of prostate tumor growth by attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium carrying plasmid-based small interfering RNAs. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5859–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saccheri F, Pozzi C, Avogadri F, Barozzi S, Faretta M, Fusi P, et al. Bacteria-induced gap junctions in tumors favor antigen cross-presentation and antitumor immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:44ra57. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang N, Zhu X, Chen L, Li S, Ren D. Oral administration of attenuated S. typhimurium carrying shRNA-expressing vectors as a cancer therapeutic. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:145–51. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.1.5195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urashima M, Suzuki H, Yuza Y, Akiyama M, Ohno N, Eto Y. An oral CD40 ligand gene therapy against lymphoma using attenuated Salmonella typhimurium. Blood. 2000;95:1258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang SN, Park SH, Lee HJ, Zheng JH, Kim HS, Bom HS, et al. Engineering of bacteria for the visualization of targeted delivery of a cytolytic anticancer agent. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1985–95. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang SN, Phan TX, Nam TK, Nguyen VH, Kim HS, Bom HS, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by a combination of Escherichia coli-mediated cytolytic therapy and radiotherapy. Mol Ther. 2010;18:635–42. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia LJ, Xu HM, Ma DY, Hu QG, Huang XF, Jiang WH, et al. Enhanced therapeutic effect by combination of tumor-targeting salmonella and endostatin in murine melanoma model. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:840–45. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.8.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishikawa H, Sato E, Briones G, Chen L-M, Matsuo M, Nagata Y, et al. In vivo antigen delivery by a Salmonella typhimurium type III secretion system for therapeutic cancer vaccines. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1946–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI28045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min JJ, Nguyen VH, Kim HJ, Hong YJ, Choy HE. Quantitative bioluminescence imaging of tumor-targeting bacteria in living animals. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:629–36. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Min JJ, Kim HJ, Park JH, Moon S, Jeong JH, Hong YJ, et al. Noninvasive real-time imaging of tumors and metastases using tumor-targeting light-emitting Escherichia coli. Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:54–61. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim K, Jeong JH, Lim D, Hong Y, Yun M, Min J-J, et al. A novel balanced-lethal host-vector system based on glmS. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yun M, Pan SO, Jiang S-N, Nguyen VH, Park S-H, Jung C-H, et al. Effect of Salmonella treatment on an implanted tumor (CT26) in a mouse model. J Microbiol. 2012;50:502–10. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-2090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill PJ, Stritzker J, Scadeng M, Geissinger U, Haddad D, Basse-Lüsebrink TC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of tumors colonized with bacterial ferritin-expressing Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soghomonyan SA, Doubrovin M, Pike J, Luo X, Ittensohn M, Runyan JD, et al. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of tumor-localized Salmonella expressing HSV1-TK. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;12:101–08. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leschner S, Weiss S. Salmonella—allies in the fight against cancer. J Mol Med. 2010;88:763–73. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forbes NS. Engineering the perfect (bacterial) cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:785–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambin P, Theys J, Landuyt W, Rijken P, van der Kogel A, van der Schueren E, et al. Colonisation of Clostridium in the body is restricted to hypoxic and necrotic areas of tumours. Anaerobe. 1998;4:183–88. doi: 10.1006/anae.1998.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Amano J, Kano Y, Taniguchi S. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for cancer gene therapy: Selective localization and growth in hypoxic tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:269–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryan RM, Green J, Lewis CE. Use of bacteria in anti-cancer therapies. BioEssays. 2006;28:84–94. doi: 10.1002/bies.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toley BJ, Forbes NS. Motility is critical for effective distribution and accumulation of bacteria in tumor tissue. Integr Biol. 2012;4:165–76. doi: 10.1039/C2IB00091A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganai S, Arenas RB, Sauer JP, Bentley B, Forbes NS. In tumors Salmonella migrate away from vasculature toward the transition zone and induce apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011;18:457–66. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasinskas RW, Forbes NS. Salmonella typhimurium lacking ribose chemoreceptors localize in tumor quiescence and induce apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3201–09. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leschner S, Westphal K, Dietrich N, Viegas N, Jablonska J, Lyszkiewicz M, et al. Tumor invasion of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is accompanied by strong hemorrhage promoted by TNF-alpha. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crull K, Bumann D, Weiss S. Influence of infection route and virulence factors on colonization of solid tumors by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;62:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Immune escape of tumors: apoptosis resistance and tumor counterattack. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:907–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westphal K, Leschner S, Jablonska J, Loessner H, Weiss S. Containment of tumor-colonizing bacteria by host neutrophils. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2952–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allport JR, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of gene and cell therapies. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:1237–46. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(01)00739-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu JC, Sundaresan G, Iyer M, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive optical imaging of firefly luciferase reporter gene expression in skeletal muscles of living mice. Mol Ther. 2001;4:297–306. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Min JJ, Nguyen VH, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of biological gene delivery vehicles for targeted cancer therapy: beyond viral vectors. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;44:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s13139-009-0006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao M, Yang M, Li XM, Jiang P, Baranov E, Li S, et al. Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy with amino acid auxotrophs of GFP-expressing Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:755–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408422102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang M, Baranov E, Moossa A, Penman S, Hoffman M. Visualizing gene expression by whole-body fluorescence imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12278–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ntziachristos V, Ripoll J, Wang LV, Weissleder R. Looking and listening to light: the evolution of whole-body photonic imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:313–20. doi: 10.1038/nbt1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2005;2:905–09. doi: 10.1038/nmeth819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ntziachristos V, Tung CH, Bremer C, Weissleder R. Fluorescence molecular tomography resolves protease activity in vivo. Nat Med. 2002;8:757–61. doi: 10.1038/nm729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Danino T, Prindle A, Kwong GA, Skalak M, Li H, Allen K, et al. Programmable probiotics for detection of cancer in urine. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:289ra84–89ra84. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Na HS, Kim HJ, Lee HC, Hong Y, Rhee JH, Choy HE. Immune response induced by Salmonella typhimurium defective in ppGpp synthesis. Vaccine. 2006;24:2027–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Senzer N, Kuhn J, Cramm J, Litz C, et al. Pilot trial of genetically modified, attenuated Salmonella expressing the E. coli cytosine deaminase gene in refractory cancer patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:737–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Critchley RJ, Jezzard S, Radford KJ, Goussard S, Lemoine NR, Grillot-Courvalin C, et al. Potential therapeutic applications of recombinant, invasive E. coli. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1224–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ashkenazi A. Targeting death and decoy receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor superfamily. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:420–30. doi: 10.1038/nrc821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lemmon MJ, van Zijl P, Fox ME, Mauchline ML, Giaccia AJ, Minton NP, et al. Anaerobic bacteria as a gene delivery system that is controlled by the tumor microenvironment. Gene Ther. 1997;4:791–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fox ME, Lemmon MJ, Mauchline ML, Davis TO, Giaccia AJ, Minton NP, et al. Anaerobic bacteria as a delivery system for cancer gene therapy: in vitro activation of 5-fluorocytosine by genetically engineered clostridia. Gene Ther. 1996;3:173–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Munn DH, Mellor AL. The tumor-draining lymph node as an immune-privileged site. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:146–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weibel S, Stritzker J, Eck M, Goebel W, Szalay AA. Colonization of experimental murine breast tumours by Escherichia coli K-12 significantly alters the tumour microenvironment. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1235–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quatromoni JG, Eruslanov E. Tumor-associated macrophages: function, phenotype, and link to prognosis in human lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:376–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Platt J, Sodi S, Kelley M, Rockwell S, Bermudes D, Low KB, et al. Antitumour effects of genetically engineered Salmonella in combination with radiation. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:2397–402. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hong H, Lim D, Kim GJ, Park SH, Sik Kim H, Hong Y, et al. Targeted deletion of the ara operon of Salmonella typhimurium enhances L-arabinose accumulation and drives pBAD-promoted expression of anti-cancer toxins and imaging agents. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3112–20. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.949527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anderson JC, Clarke EJ, Arkin AP, Voigt CA. Environmentally controlled invasion of cancer cells by engineered bacteria. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:619–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dai Y, Toley BJ, Swofford CA, Forbes NS. Construction of an inducible cell-communication system that amplifies Salmonella gene expression in tumor tissue. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110:1769–81. doi: 10.1002/bit.24816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leschner S, Deyneko IV, Lienenklaus S, Wolf K, Bloecker H, Bumann D, et al. Identification of tumor-specific Salmonella typhimurium promoters and their regulatory logic. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2984–94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mengesha A, Dubois L, Lambin P, Landuyt W, Chiu RK, Wouters BG, et al. Development of a flexible and potent hypoxia-inducible promoter for tumor-targeted gene expression in attenuated salmonella. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1120–28. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.9.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schleif R. AraC protein: a love-hate relationship. BioEssays. 2003;25:274–82. doi: 10.1002/bies.10237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baron U, Freundlieb S, Gossen M, Bujard H. Co-regulation of two gene activities by tetracycline via a bidirectional promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3605–06. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anderson DG, Kowalczykowski SC. Reconstitution of an SOS response pathway: derepression of transcription in response to DNA breaks. Cell. 1998;95:975–79. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mengesha A, Dubois L, Lambin P, Landuyt W, Chiu R, Wouters B, et al. Development of a flexible and potent hypoxia-inducible promoter for tumor-targeted gene expression in attenuated Salmonella. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1120–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.9.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]