Abstract

The efficacy of biochar as an environmentally friendly agent for non-point source and climate change mitigation remains uncertain. Our goal was to test the impact of biochar amendment on paddy rice nitrogen (N) uptake, soil N leaching, and soil CH4 and N2O fluxes in northwest China. Biochar was applied at four rates (0, 4.5, 9 and13.5 t ha−1 yr−1). Biochar amendment significantly increased rice N uptake, soil total N concentration and the abundance of soil ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), but it significantly reduced the soil NO3 −-N concentration and soil bulk density. Biochar significantly reduced NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching. The C2 and C3 treatments significantly increased the soil CH4 flux and reduced the soil N2O flux, leading to significantly increased net global warming potential (GWP). Soil NO3 −-N rather than NH4 +-N was the key integrator of the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes. Our results indicate that a shift in abundance of the AOA community and increased rice N uptake are closely linked to the reduced soil NO3 −-N concentration under biochar amendment. Furthermore, soil NO3 −-N availability plays an important role in regulating soil inorganic N leaching and net GWP in rice paddies in northwest China.

Introduction

Synthetic nitrogen (N) fertilizer is currently the largest source of anthropogenic reactive N worldwide1 and has enabled the doubling of world food production in the past four decades2. However, excessive fertilizer N intended for crops results in environmental pollution problems, such as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and surface runoff and leaching3. The three main greenhouse gases (i.e., CO2, CH4, and N2O) in combination contribute to more than 90% of anthropogenic climate warming4. N leaching may deplete soil fertility, accelerate soil acidification and reduce crop yields5.

Global rice paddies occupied more than 1.61 × 108 ha of land and produced 4.82 × 108 T yr−1 of grain in 2015~2016, creating a major challenge for N leaching and greenhouse gas emission mitigation6, 7. In China, 23% of the nation’s croplands are used for rice production, accounting for approximately 20% of the world’s total8. A meta-analysis showed lower N use efficiency of 28.1% during the period 2000–2005 for rice in China9, compared with 52% in America and 68% in Europe10. The average total N leaching rate was 2.2% in paddy fields11. The total amounts of CH4 and N2O emissions from China’s rice paddies are estimated to be 7.7~8.0 Tg CH4 yr−1 and 88.0~98.1 Gg N2O-N yr−1, respectively12, 13. Judicious methods are needed to reduce GHG emissions and N leaching losses to achieve lower agricultural environmental costs14, while not impairing the capacity of ecosystems to ensure food security.

Biochar is a solid carbon-rich organic material generated by pyrolysis or gasification of biomass residues in the absence of oxygen at a relatively low temperature. Biochar application to agricultural soils has the potential to slow carbon and N release15, 16 via the high content of recalcitrant organic carbon in the biochar and concomitant changes in soil properties, which affect microbial activity17. Recent reviews have highlighted biochar as a possible method to decrease soil CH4 and N2O emissions18, 19 and reduce N leaching20.

The effects of biochar on paddy soil CH4 emissions remain controversial depending on the biochar type, climatic conditions and soil properties21. A laboratory incubation study showed that amendment with bamboo biochar and rice-straw biochar decreased paddy soil CH4 emissions by up to 51% and 91%, respectively22, while wheat-straw biochar amendment increased soil CH4 emission by 37%23. In addition, no significant difference in soil CH4 flux was found between a biochar plot and a control plot in Germany24. Biochar application can affect N transformation and N fate in soil16, 25. The soil N2O flux increased significantly in some studies26, 27 but substantially decreased or remained unchanged in others23, 28. These contrasting results emphasize the need for more studies to assess the role of biochar in mitigating paddy soil CH4 and N2O fluxes. Moreover, the mechanisms of action are not well understood, which has impeded the adoption of biochar in a wide range of rice ecosystems.

Nitrification, through which microorganisms oxidize ammonium (NH4 +) to create nitrate (NO3 −), releasing N2O as a by product, has long been a concern of scientists in paddy soils. Many studies found lower N leaching after biochar amendment in laboratory and field experiments20, 29. However, the underlying mechanisms are still controversial. Recent studies have demonstrated that increased water-holding capacity, enhanced microbial biomass and altered bacterial community structure in soils may contribute to the reduction of N leaching20. Other studies suggest that reduced N leaching may result from improved plant N use30, 31. NH3 oxidation to NO2 −, the first and rate-limiting step of nitrification, is catalyzed by ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB)32. Due to the homology of methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase enzymes, the same habitats, and the variety of analog substrates, CH4 in the soil can be simultaneously oxidized by both methanotrophs and ammonia oxidizers33, 34. It is essential to explore the links between ammonia oxidizers and the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes in the field under biochar amendment.

In the upper reaches of the Yellow River basin of China, preliminary studies revealed that biochar amendment significantly improves N use efficiency35 and reduces total inorganic N leaching36. Consequently, we hypothesized that biochar amendment decreases soil N2O emission and reduces NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching. We also hypothesized that biochar amendment increases soil CH4 emissions due to the labile carbon input and the positive priming effects of biochar and also increases crop productivity. The aim of the present study was to provide insight into the effects of biochar amendment on paddy soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching and soil CH4 and N2O emissions throughout the entire growth period. By considering the net global warming potential (GWP) of the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes and the NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching under different treatments, it should be possible to determine the optimal amount of biochar application for China’s rice paddies.

Materials and Methods

Study site

This experiment was conducted at Yesheng Town (106°11′35″ E, 38°07′26″ N) in Wuzhong City, China. The temperate continental monsoon climate dominates the region, with a mean temperature of 9.4 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 192.9 mm. The soil is classified as anthropogenic alluvial soil, with a soil texture of 18.25% clay, 53.76% silt, and 27.99% sand. The top soil (0–20 cm) organic matter is 16.1 g kg−1, the total N is 1.08 g kg−1, and the soil bulk density is 1.33 g cm−3.

Experimental design and rice management

Biochar was applied to the field plots at rates of 0 (C0), 4.5 (C1), 9.0 (C2) and 13.5 t ha−1 yr−1 (C3). Each treatment was performed in triplicate. A total of 12 plots (30 m × 20 m) were established, and each was separated by plastic film to 130 cm in depth, preventing water interchange between adjacent plots. Each plot was irrigated with an equal amount of water (approximately 14500 m3 ha−1 yr−1). The biochar was produced by pyrolysis of wheat straw at 350–550 °C by the Sanli New Energy Company, Henan Province, China. The biochar had C, N, P and K contents of 65.7%, 0.49%, 0.1% and 1.6%, respectively, with a pH (H2O) of 7.7835.

Urea was applied at 240 kg N ha−1, of which 50% was applied as a base fertilizer before transplanting (26 May, 2014), 30% was applied at the tillering stage (6 June, 2014), and the remaining 20% was applied at the elongation stage (25 June, 2014). Double superphosphate and KCL were also applied as basal fertilizers before transplanting at rates of 90 kg P2O5 ha−1 and 90 kg K2O ha−1, respectively. Biochar and fertilizers were broadcast on the soil surface and incorporated into the soil by plowing to a depth of approximately 13 cm in May 2014. To maintain consistency, plowing was also performed for the plots without biochar. Rice (Oryza sativa L., cv. 96D10) was sown in a nursery bed on 1 May. Rice seedlings were transplanted on 28 May and harvested on 12 October 2014. Crop management was consistent across plots.

Measurement of the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes

The soil CH4 and N2O fluxes were measured using a static opaque chamber and gas chromatography, as described by Wang et al.33. Sampling of emitted gases was conducted between 8:00 and 10:00 in the morning. Fluxes were measured twice a week after irrigation and fertilization before the booting stage. Afterwards, the measurement frequency decreased to three times a month during the rice booting, filling and maturity stages and to two times a month during the fallow period. The gas fluxes were measured on 21 occasions during the observation period. The concentrations of CH4 and N2O in the gas samples were simultaneously analyzed within 24 h using a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and an electron capture detector (ECD). High-purity N2 and H2 were used as the carrier gas and fuel gas, respectively. The ECD and FID were heated to 350 °C and 200 °C, respectively, and the column oven was kept at 55 °C. The CH4 and N2O fluxes were calculated based on the rate of change in concentration within the chamber, which was estimated as the linear or nonlinear regression slope between concentration and time37.

Soil sampling and analysis

Soil samples (0–20 cm) were collected three times: tillering stage (16 June), filling stage (10 August) and harvest stage (12 October). Five soils from two diagonal lines through each plot were collected and pooled into one composite sample. Soils were sieved to 2-mm mesh size in the field and were then transported to the lab in a biological refrigerator. Soil samples were stored at −80 °C before analysis. Soil NH4 +-N and NO3 −-N were determined using a continuous-flow auto analyzer (Seal AA3, Germany). Soil bulk density was measured using a 100 cm3 cylinder. The total N (TN) contents in the bulk soil were determined by dry combustion using the Kjeldahl method38.

Soil DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of soil using the Fast DNA®SPIN Kit (Qbiogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) for soil following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was checked on 1% agarose gel, and the DNA concentration was assessed using a Nanodrop®D-1000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Tenfold diluted DNA was used in the PCR analysis. Primer pairs Arch-amoAF/Arch-amoAR 39 and amoA1F/amoA2R 40 were used for the qPCR of AOA and AOB amoA genes, as described by Wang et al.33. Product specificity was checked by melt curve analysis at the end of the PCR runs and by visualization via agarose gel electrophoresis. A known copy number of plasmid DNA for AOA or AOB was used to generate a standard curve. For all assays, the PCR efficiency was 90–100% and r 2 was 0.95–0.99.

Soil leachate sampling and analysis

Soil water samples used for the leaching calculations were collected from lysimeters, as described by Riley et al.41. Four PPR (polypropylene random) equilibrium-tension lysimeters (ETLs) (0.19 m2) were installed at the desired depth (20, 60 and 100 cm) below the soil surface for each treatment condition. Soil leachate samples were collected using 100 ml plastic syringes and were transferred to a plastic tube and stored at 4 °C before analysis. Samples were taken on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 after transplanting and topdressing; subsequent sampling was conducted at 10-day intervals. Soil leachate samples were collected 14 times during the observation period. The NH4 +-N and NO3 −-N leaching losses were calculated by multiplying the N concentration by the leachate volume.

Rice yield and N uptake

At rice maturity, rice aboveground biomass was estimated by manually harvesting three 0.5 m2 areas. Rice straw and grain were oven-dried to a constant weight at 80 °C, weighed, finely ground, sieved, and analyzed for total N using the Kjeldahl method38. Total N uptake was calculated from the sum of the N mass in the straw and grain harvested from each plot.

Statistical analyses

GWP is an index of the cumulative radiative forcing between the present and some chosen later time by a unit mass of gas emitted under specific conditions42. To compare net GWP after biochar amendment to soil, we calculated the CO2 equivalents for CH4 and N2O for a time horizon of 100 yr (assuming a GWP of 25 for CH4 and 298 for N2O) using the following equation.

Repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the least significant difference (LSD) test were applied to examine the differences in N leaching, soil CH4 and N2O fluxes, and soil microbial amoA gene copy numbers among the different treatments. Biochar amendment was set as a between-subjects factor, and the measurement period was selected as a within-subjects variable. We performed one-way ANOVA with an LSD test to evaluate the effects of biochar amendment on the soil properties, rice yield and N uptake. Linear regression analyses were used to examine the relationships among the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes, the microbial amoA gene copy numbers and the soil inorganic N concentrations. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software (version 16.0), and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05, unless otherwise stated. All figures were drawn using SigmaPlot software (version 10.0).

Results

Soil properties, rice yield and N uptake

In the C0 treatment, the average concentration of soil NO3 −-N was 26.52 mg kg−1 during the whole observation period (Table 1). The soil NO3 −-N concentration was reduced significantly by 15.10%, 32.13% and 51.02% in the C1, C2 and C3 treatments (Table 1). However, the soil NH4 +-N concentration was only significantly decreased in the C1 treatment(Table 1). Biochar amendment significantly increased soil TN by 10.01~22.22% and significantly decreased bulk density by 4.51~7.81% compared with the treatment without biochar (Table 1). Biochar amendment tended to decrease soil pH (Table 1, P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Soil inorganic N, soil TN, bulk density and soil pH value under the four experimental treatments.

| Treatment | NO3 −-N (mg kg−1) | NH4 +-N (mg kg−1) | TN (g kg−1) | Bulk density (g cm−3) | Soil pH value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | 26.52 ± 3.03a | 9.81 ± 0.62a | 1.08 ± 0.01c | 1.33 ± 0.01a | 8.62 ± 0.02a |

| C1 | 19.14 ± 0.23b | 8.44 ± 0.40b | 1.15 ± 0.01b | 1.28 ± 0.02b | 8.58 ± 0.04a |

| C2 | 15.30 ± 0.97bc | 8.72 ± 0.18ab | 1.20 ± 0.02b | 1.28 ± 0.02b | 8.56 ± 0.03a |

| C3 | 12.99 ± 0.39c | 9.25 ± 0.32ab | 1.32 ± 0.02a | 1.27 ± 0.01b | 8.56 ± 0.03a |

Data are mean ± SE. Lowercase letter in the same column represents significant differences among experimental treatments at the level of 0.05.

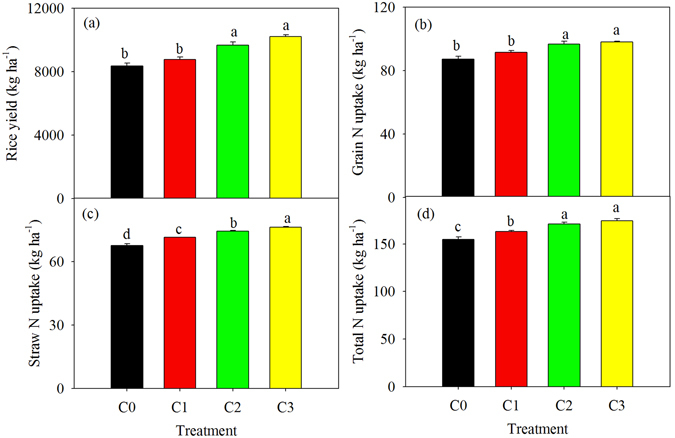

In the control, the rice yield and grain N uptake were 8357 kg ha−1 and 87.2 kg ha−1, respectively. Biochar amendment significantly increased the rice yield and grain N uptake compared with the C0 treatment for the C2 and C3 treatments (Fig. 1a,b). Straw N uptake increased with increasing biochar application rate. Moreover, the relative increase induced by biochar amendment on straw N uptake was 5.62%, 10.06% and 12.87% for the C1, C2 and C3 treatments, respectively (Fig. 1c). In addition, total N uptake was increased by 5.43%, 10.53% and 12.61% in C1, C2 andC3, respectively, compared withC0 (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Rice yield (a), grain N uptake (b), straw N uptake (c) and total N uptake (d) under the four experimental treatments. Data are shown as means with standard errors. Different letters in the same subfigure indicate significant differences of different treatment according to the LSD test (P < 0.05).

Soil NO3−-N and NH4+-N leaching

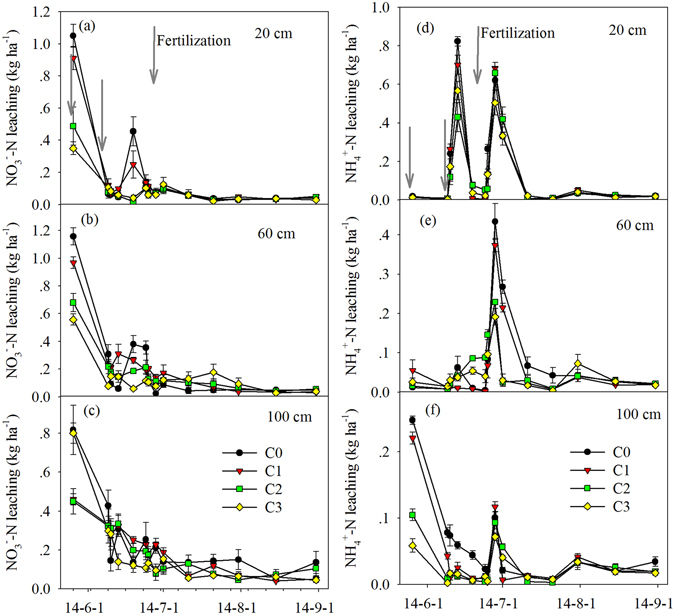

There was a clear seasonal variation in NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching at various soil depths (Fig. 2, Table 2, P < 0.001). Supplementary fertilizer N application during the tillering and elongation stages induced NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching peaks. At greater depth, the NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching peaks were dampened. There were no major changes in the NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching during the final two months (Fig. 2). The average NO3 −-N leaching increased with soil depth, whereas NH4 +-N leaching decreased with soil depth (Table 2). Biochar application significantly reduced the mean NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching (Table 2). C1 had significantly decreased NO3 −-N leaching at a depth of 100 cm and NH4 +-N leaching at depths of 60 cm and 100 cm, while C2 and C3 showed significantly decreased NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching throughout the soil profile (Table 2). Furthermore, significant interactions were found between the observation period and biochar treatment, except for the NO3 −-N leaching at 100 cm (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Variation of soil NO3 −-N (a–c) and NH4 +-N (d–f) leaching under the four experimental treatments. Data are shown as means with standard errors.

Table 2.

Soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching at various soil depths affected by different treatments over the entire experimental period.

| Treatments | NO3 −-N (mg L−1) | NH4 +-N (mg L−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 cm | 60 cm | 100 cm | 20 cm | 60 cm | 100 cm | |

| C0 | 12.49 ± 0.45a | 14.87 ± 0.61a | 18.60 ± 0.12a | 11.84 ± 0.46a | 6.29 ± 0.13a | 4.40 ± 0.20a |

| C1 | 11.56 ± 0.06a | 15.73 ± 0.19a | 15.21 ± 0.29b | 12.10 ± 0.38a | 4.76 ± 0.24b | 3.15 ± 0.03b |

| C2 | 7.26 ± 0.48b | 13.01 ± 0.82b | 15.16 ± 1.14b | 10.12 ± 0.27b | 3.89 ± 0.20c | 2.55 ± 0.11c |

| C3 | 6.87 ± 0.33b | 11.25 ± 0.56b | 13.76 ± 0.17b | 9.77 ± 0.46b | 3.54 ± 0.28c | 2.11 ± 0.19c |

| ANOVA results | ||||||

| Period | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.007 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Period × Treatment | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.843 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are mean ± SE. Lowercase letter in the same column represents significant differences among experimental treatments at the level of 0.05.

Soil CH4 and N2O emissions

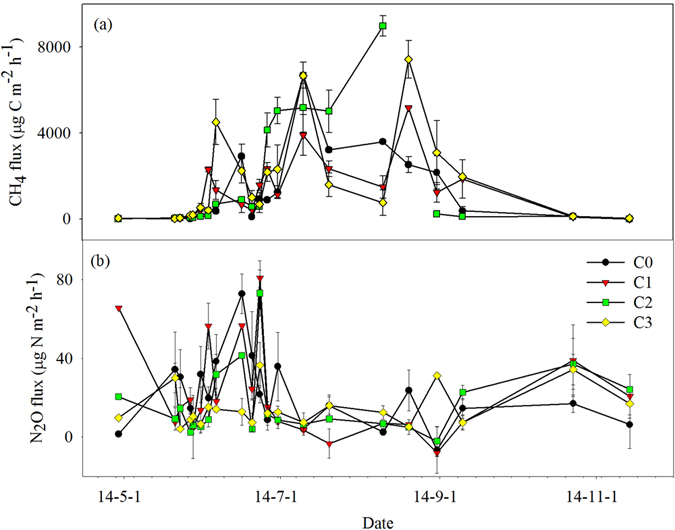

The soil CH4 flux significantly varied among growth periods, with the maximum occurring in the booting and filling stages (Fig. 3a, Table 3, P < 0.001). In C0, the soil CH4 flux ranged from −9.60 µg C m−2 h−1 to 6688.37 µg C m−2 h−1, with an average of 1264.54 µg C m−2 h−1 (Fig. 3a). The cumulative annual soil CH4 emission was 110.77 kg C ha−1 (Table 3). Biochar amendment significantly increased cumulative soil CH4 emissions (Table 3, P = 0.008). C2 and C3 showed significantly increased cumulative soil CH4 emissions (by 35.16% and 40.62%, respectively) compared with C0 (Table 3). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction for soil CH4 flux between observation period and treatment (Table 3, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Variation of CH4 (a) and N2O (b) fluxes under the four experimental treatments. Data are shown as means with standard errors.

Table 3.

Soil CH4 and N2O fluxes, net GWP, abundances of soil ammonia-oxidizers affected by different treatments over the entire experimental period.

| Treatments | CH4 (kg C ha−1) | N2O (kg N ha−1) | GWP (kg CO2 ha−1) | AOA (copies g−1 dry soil) | AOB (copies g−1 dry soil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | 110.77 ± 9.19b | 1.87 ± 0.21a | 3325.20 ± 261.62c | 6.25 ± 0.03c | 6.13 ± 0.08a |

| C1 | 116.74 ± 5.83b | 1.73 ± 0.10ab | 3432.92 ± 117.90bc | 6.66 ± 0.12b | 6.32 ± 0.07a |

| C2 | 149.72 ± 10.50a | 1.40 ± 0.05b | 4160.92 ± 273.83ab | 6.54 ± 0.06b | 6.24 ± 0.11a |

| C3 | 155.76 ± 12.81a | 1.33 ± 0.12b | 4289.74 ± 341.97a | 7.02 ± 0.12a | 6.11 ± 0.08a |

| ANOVA results | |||||

| Period | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.074 | 0.011 | |

| Treatment | 0.008 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 0.349 | |

| Period × Treatment | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.684 | |

Data are mean ± SE. Lowercase letter in the same column represents significant differences among experimental treatments at the level of 0.05.

Soil N2O flux showed an obvious variation among growth stages (Fig. 3b, Table 3, P < 0.001). The maximum soil N2O emission occurred during the rice tillering stage (Fig. 3b). Soil N2O flux fluctuated from 2.55 µg N m−2 h−1 to 72.70 µg N m−2 h−1inC0, with an average of 63.88 µg N m−2 h−1 (Fig. 3b). This rate translated into a cumulative annual soil N2O emission of 1.87 kg N ha−1 (Table 3). Biochar amendment significantly reduced soil N2O emissions (Table 3, P = 0.039), and the interaction between observation period and treatment was also significant (Table 3, P < 0.001). C2 and C3 showed significantly decreased annual cumulative N2O emissions (by 25.13% and 28.88%, respectively, relative to C0) (Table 3). However, the C1 treatment decreased soil N2O emissions (Table 3).

Biochar amendment consistently increased the net GWP, and C2 and C3 showed the largest increases (29.01% and 25.13%, respectively) (Table 3). However, the increase in net GWP elicited by the C1 treatment was only 3.24% (Table 3).

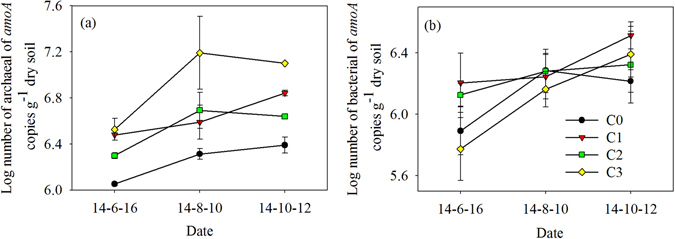

Abundance of soil AOA and AOB communities

Soil AOA amoA copy numbers exhibited a slight seasonal variation (Fig. 4a, Table 3, P = 0.074), while soil AOB amoA copy numbers showed a clear pattern of seasonal changes (Fig. 4b, Table 3, P = 0.011). Biochar amendment significantly increased soil AOA amoA copy numbers (Table 3, P < 0.001). The highest AOA amoA gene copy numbers were observed in the C3 treatment(12.32% greater than that of C0) (Table 3). Conversely, there was no significant difference in soil AOB amoA copy numbers among the four treatment (Table 3, P = 0.349).

Figure 4.

Variation of AOA (a) and AOB (b) amoA gene copy numbers and arithmetic mean under the four experimental treatments. Data are shown as means with standard errors.

Relationships between soil fluxes and ammonia-oxidizer abundances and soil inorganic N concentrations

The soil CH4 fluxes were negatively linearly correlated with the soil NO3 −-N concentration (Table 4). The soil N2O fluxes were negatively correlated with the soil AOA abundance and positively correlated with the soil NO3 −-N concentration (Table 4). The soil AOA abundance was negatively correlated with the soil NO3 −-N concentration, whereas the soil AOB abundance was not correlated with any of the measured soil fluxes or inorganic N concentrations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients (R2) for the relationships among soil CH4 and N2O fluxes, soil ammonia-oxidizers, soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N concentrations.

| CH4 | N2O | AOA | AOB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOA | 0.24 | 0.43(−)* | ||

| AOB | 0.04 | 0.06 | — | — |

| NO3 −-N | 0.45(−)* | 0.65(+)** | 0.59(−)** | 0.07 |

| NH4 +-N | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

Note: Significance: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. For all correlations, n = 12. (+), positive relationship; (−), negative relationship.

Discussion

Effects of biochar amendment on soil NO3−-N and NH4+-N leaching

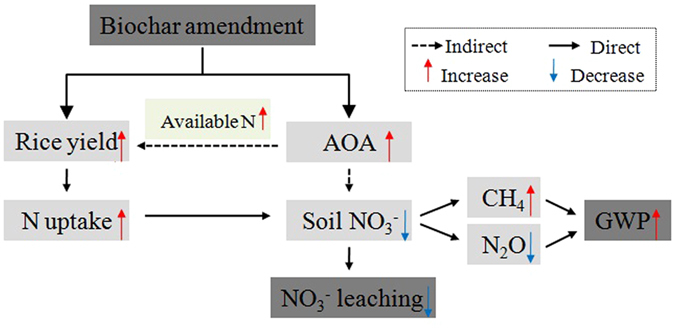

In our study, significant reductions in soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching were observed in the C2 and C3 treatment conditions, while the significant decreases in the C1 treatment were NO3 −-N leaching at the depth of 100 cm and NH4 +-N leaching at depths of 60 cm and 100 cm (Table 2). These results confirmed our first hypothesis that biochar amendment reduces soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching. Increases in N retention or absorption in soil29, 43 and stimulation of crop N uptake44 have generally been hypothesized to be the primary causes of reduced N leaching after biochar application. In our study, biochar amendment significantly increased the total soil N concentration and rice yield (Table 1), consistent with the meta-analysis results reported by Biederman and Harpole45. Furthermore, biochar amendment increased AOA activity (Table 4), producing more available N for crop growth and increased rice N uptake (Fig. 5). The reduced soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N concentrations decreased the inorganic N pool for leaching (Table 1). Therefore, the reduced soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N concentrations induced by biochar application may be the main cause of the reduction in NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching (Fig. 5). In addition, the increased soil water holding capacity due to the reduced soil bulk density (Table 1) may have also reduced NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching46.

Figure 5.

Potential mechanisms of paddy soil N leaching and total GWP in response to biochar amendment.

Effects of biochar amendment on the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes

The net CH4 flux from soil is the sum of production and oxidation. The effects of biochar amendment on the CH4 flux were thus unclear. In agreement with previous studies24, 47, the application of biochar at rates of 9 t ha−1 yr−1 and 13.5 t ha−1 yr−1 significantly increased the soil CH4 flux by 35.16% and 40.62%, respectively (Table 3). The promotion of the soil CH4 flux was comparable to that of the Tai Lake plain in China for biochar amendment at rates of 10 t ha−1and 40 t kg ha−1 23. This was attributed to the following three aspects. First, the soil NH4 +-N accumulation decreased soil CH4 oxidation by altering the activity and composition of the methanotrophic community48. However, biochar amendment did not significantly change the soil NH4 +-N accumulation (Table 1), and there was no significant relationship between the soil CH4 flux and soil NH4 +-N concentration (Table 4). Wang et al.49 found that soil NO3 −-N accumulation could significantly promote soil CH4 uptake. The lower soil CH4 uptake was due to the decreased soil NO3 −-N concentration under biochar amendment (Table 1), which increased the soil CH4 emissions in our study (Table 3, Fig. 5). The significant negative relationship between the soil NO3 −-N concentration and the soil CH4 flux reflected this prediction (Table 4). Second, methanotrophs use the sorbed organic compounds in addition to CH4 because methanotrophs can utilize a variety of substrates50. Therefore, biochar amendment reduced the net soil CH4 oxidation51. Third, Knoblauch et al.52 reported that the labile components of biochar increase the substrate supply and create a favorable environment for methanogens53. The lower pH in our biochar plots may have promoted methanogenic archaea, which have an optimal pH of 754. Thus, a larger archaeal population may temporarily have increased CH4 emissions in the biochar treatment55 until the emissions declined due to the oxic environment. However, because we only measured the net effects, we could not distinguish between reduced soil methanotrophic activity and increased methanogenic activity in this study.

Suppression of soil N2O emissions following biochar amendment has been observed both under laboratory conditions25, 26 and in the field23, 47. Enhanced soil aeration27, altered ammonia-oxidizer and denitrifier activity56, sorption of NH4 +-N or NO3 −-N by biochar12 and the presence of inhibitory compounds such as ethylene57 have been suggested as mechanisms to explain the reduction inN2O flux with biochar amendment. In anaerobic paddy soil, N2O production from denitrification is thought to be the dominant source. Baggs58 suggested that decreased total N denitrification and enhanced reduction of N2O to N2 can lead to lower N2O denitrification in soil. A reduction in NO3 −-N availability would decrease the total denitrified N and would reduce the ratio of N2O/(N2 + N2O)17. In our study, biochar amendment reduced the soil NO3 −-N concentration by accelerating ammonia oxidation (Fig. 4, Table 3) and promoting total N uptake in rice (Fig. 1). The significant negative correlation between the soil NO3 −-N concentration and soil AOA abundance provided direct evidence for this result (Table 4). Soil NO3 −-N availability was positively correlated with soil N2O flux (Table 4), which could partially explain the reduction in soil N2O flux in the studied paddy soil (Fig. 5). In addition, evidence for the decreased N2O denitrification was provided by the decreased soil bulk density after biochar amendment (Table 1). Soil pH was not significantly changed after biochar amendment at our study site (Table 1). However, soil Eh was not monitored when the gas samples were taken in situ. Mechanisms associated with the oxidation and reduction of nitrogen species need to be studied under the alternating redox conditions on the surface of biochar.

However, our flux results were drawn from relatively few measurements. The gas fluxes were measured on 19 occasions during 150 days of rice growth, with an average sampling interval of 8 days. This frequency was slightly lower than the average 6.5 day interval of the reviewed rice paddy studies in China with single biochar amendment and biochar combined with NPK compound fertilizer (Supplementary Table S1). The effects of biochar amendment on the soil CH4 flux are contradictory, including positive, negative, and neutral effects. Moreover, biochar amendment is mainly reported to decrease soil N2O flux. Increased soil CH4 flux and decreased soil N2O flux were observed in our study. This evidence suggests that our conclusions can be drawn from relatively few measurements.

Biochar is considered to be an effective tool to mitigate GWP via carbon sequestration in soil and to influence carbon mineralization through priming effects. In the present study, the changes in net GWP were not significant between C1 and C0 treatments, while biochar amendment significantly increased paddy soil CH4 emissions and decreased N2O emissions in the C2 and C3 treatments, leading to a significantly increased net GWP (Table 3). This result is in line with that of a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China23. Our results indicate that higher amounts of biochar amendment are associated with a risk of increased paddy net GWP in northwest China (Fig. 5). The stimulation effects of biochar on native soil organic carbon mineralization decreases with time due to the depletion of labile SOC from the initial positive priming and stabilization of native SOC via biochar-induced organ-mineral interactions during 5-year laboratory incubations59. In another 120-day incubation study, the time effects showed an initial increase followed by a decrease and stabilization, resulting in a significantly increased sequestration of carbon in the soil over the long term compared with conventional biowaste amendments60. In our study, improved rice yield and reduced soil nitrous oxide emissions contributed to the mitigation potential of biochar amendment. However, the response of native soil organic carbon mineralization to biochar amendment remains uncertain. Relative priming effects and cumulative CO2 emissions studies are needed to evaluate the GWP of biochar amendment in our paddy soil.

Conclusions

The effects of biochar amendment on soil N leaching and soil CH4 and N2O fluxes were investigated in paddy soil in northwest China. We found that biochar amendment significantly decreased soil NO3 −-N and NH4 +-N leaching, but that the C2 and C3 treatments significantly increased soil CH4 emissions and reduced N2O emissions, leading to significantly increased net GWP. Biochar amendment significantly increased soil AOA abundance and rice N uptake. Soil NO3 −-N availability can explain the responses of soil N leaching and soil CH4 and N2O fluxes to biochar amendment. Our results indicated are commended dose of biochar amendment of 4.5 t ha−1 yr−1 with conventional N application in the study area. The responses of the soil CH4 and N2O fluxes to biochar amendment were also influenced by the interannual variability in climate, temperature and precipitation. The long-term effects of biochar amendment on N leaching and net GWP in rice production required further investigation to identify the most cost-effective and environmentally friendly management practices for rice culture.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Water Pollution and Treatment Science and Technology Major Project (No. 201ZX07201-009), Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41130748, 31660957, 41471143), Special Foundation for Basic Scientific Research of Central Public Welfare Institute (No. BSRF201306), and Priority Funds for Ningxia Scientific and Technological Innovation (No. NKYJ-15-05).

Author Contributions

Y.W. and A.Z. conceived the study. R.L., S.Y., Y.Z. and H.L. sampled and analyzed the samples. Y.W. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Y.L., S.Y., and Z.Y. contributed to discussing the results and editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01173-w

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fowler, D. et al. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos T R Soc B368, doi:Artn 2013016410.1098/Rstb.2013.0164 (2013).

- 2.Tilman D. Global environmental impacts of agricultural expansion: the need for sustainable and efficient practices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96:5995–6000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.5995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitousek PM, et al. Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: sources and consequences. Ecol Appl. 1997;7:737–750. [Google Scholar]

- 4.IPCC. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York: Cambridge University Press (2013).

- 5.Laird D, Fleming P, Wang BQ, Horton R, Karlen D. Biochar impact on nutrient leaching from a Midwestern agricultural soil. Geoderma. 2010;158:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2010.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju, X. T. et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. P Natl Acad Sci USA106, doi:10.1073/pnas.0902655106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chauhan, B. S., Jabran, K. & Mahajan, G. Rice production worldwide. Cham, Switzerland: Sprinker International Publishing (2017)

- 8.Frolking, S. et al. Combining remote sensing and ground census data to develop new maps of the distribution of rice agriculture in China. Global Biogeochem Cy16 (2002).

- 9.Zhang FS, et al. Nutrient use efficiencies of major cereal crops in China and measures for improvement. Acta Pedologica Sinica. 2008;45:915–924. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladha JK, Pathak H, Krupnik TJ, Six J, van Kessel C. Efficiency of fertilizer nitrogen in cereal production: Retrospects and prospects. Advances in Agronomy. 2005;87:85–156. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(05)87003-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu YT, Liao QJH, Wang JW, Yan XY. Statistical analysis and estimation of N leaching from agricultural fields in China. Soils. 2011;43:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan, X. Y., Cai, Z. C., Ohara, T. & Akimoto, H. Methane emission from rice fields in mainland China: amount and seasonal and spatial distribution. J Geophys Res-Atmos108, doi:Artn 450510.1029/2002jd003182 (2003).

- 13.Zheng, X., Han, S., Huang, Y., Wang, Y. & Wang, M. Re‐quantifying the emission factors based on field measurements and estimating the direct N2O emission from Chinese croplands. Global Biogeochem Cy18 (2004).

- 14.Chien SH, Prochnow LI, Cantarella H. Recent developments of fertilizer production and use to improve nutrient efficiency and minimize environmental impacts. Advances in Agronomy, Vol 102. 2009;102:267–322. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(09)01008-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinbeiss S, Gleixner G, Antonietti M. Effect of biochar amendment on soil carbon balance and soil microbial activity. Soil Biol Biochem. 2009;41:1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira EIP, et al. Biochar alters nitrogen transformations but has minimal effects on nitrous oxide emissions in an organically managed lettuce mesocosm. Biol Fert Soils. 2015;51:573–582. doi: 10.1007/s00374-015-1004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cayuela, M. L. et al. Biochar and denitrification in soils: when, how much and why does biochar reduce N2O emissions? Sci Rep-Uk3, doi:Artn 173210.1038/Srep01732 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Jeffery S, Verheijen FGA, Kammann C, Abalos D. Biochar effects on methane emissions from soils: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;101:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cayuela ML, et al. Biochar’s role in mitigating soil nitrous oxide emissions: A review and meta-analysis. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2014;191:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2013.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu N, Tan GC, Wang HY, Gai XP. Effect of biochar additions to soil on nitrogen leaching, microbial biomass and bacterial community structure. Eur J Soil Biol. 2016;74:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2016.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee A, Lal R. Biochar impacts on soil physical properties and greenhouse gas emissions. Agronomy. 2013;3:313–339. doi: 10.3390/agronomy3020313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YX, et al. Reducing CH4 and CO2 emissions from waterlogged paddy soil with biochar. J Soil Sediment. 2011;11:930–939. doi: 10.1007/s11368-011-0376-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang AF, et al. Effect of biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2010;139:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2010.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knoblauch C, Maarifat AA, Pfeiffer EM, Haefele SM. Degradability of black carbon and its impact on trace gas fluxes and carbon turnover in paddy soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:1768–1778. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh BP, Hatton BJ, Singh B, Cowie AL, Kathuria A. Influence of biochars on nitrous oxide emission and nitrogen leaching from two contrasting soils. J Environ Qual. 2010;39:1224–1235. doi: 10.2134/jeq2009.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spokas KA, Reicosky DC. Impacts of sixteen different biochars on soil greenhouse gas production. Ann. Environ. Sci. 2009;3:4. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanai Y, Toyota K, Okazaki M. Effects of charcoal addition on N2O emissions from soil resulting from rewetting air-dried soil in short-term laboratory experiments. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2007;53:181–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2007.00123.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie ZB, et al. Impact of biochar application on nitrogen nutrition of rice, greenhouse-gas emissions and soil organic carbon dynamics in two paddy soils of China. Plant Soil. 2013;370:527–540. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1636-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guerena D, et al. Nitrogen dynamics following field application of biochar in a temperate North American maize-based production system. Plant Soil. 2013;365:239–254. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1383-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan KY, Van Zwieten L, Meszaros I, Downie A, Joseph S. Agronomic values of greenwaste biochar as a soil amendment. Aust J Soil Res. 2007;45:629–634. doi: 10.1071/SR07109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner C, et al. Nitrogen retention and plant uptake on a highly weathered central Amazonian Ferralsol amended with compost and charcoal. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science-Zeitschrift Fur Pflanzenernahrung Und Bodenkunde. 2008;171:893–899. doi: 10.1002/jpln.200625199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Könneke M, et al. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature. 2005;437:543–546. doi: 10.1038/nature03911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang YS, et al. Relationships between ammonia-oxidizing communities, soil methane uptake and nitrous oxide fluxes in a subtropical plantation soil with nitrogen enrichment. Eur J Soil Biol. 2016;73:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2016.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Y, Huang R, Wang BZ, Bodelier PLE, Jia ZJ. Competitive interactions between methane- and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria modulate carbon and nitrogen cycling in paddy soil. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:3353–3368. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-3353-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang AP, et al. Effects of biochar on rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency in the Ningxia Yellow river irrigation region. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer. 2015;21:1352–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang AP, et al. Effects of biochar on nitrogen losses and rice yield in anthropogenic -alluvial soil irrigated with Yellow river water. Journal of Agro-Environment Science. 2014;33:2395–2403. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YS, Wang YH. Quick measurement of CH4, CO2 and N2O emissions from a short-plant ecosystem. Adv Atmos Sci. 2003;20:842–844. doi: 10.1007/BF02915410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bao, S. D. Soil and agricultural chemistry analysis. China Agriculture Press, Beijing, 52–60 (2000).

- 39.Francis CA, Roberts KJ, Beman JM, Santoro AE, Oakley BB. Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14683–14688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506625102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rotthauwe J-H, Witzel K-P, Liesack W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1997;63:4704–4712. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4704-4712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riley WJ, Ortiz-Monasterio I, Matson PA. Nitrogen leaching and soil nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium levels under irrigated wheat in Northern Mexico. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys. 2001;61:223–236. doi: 10.1023/A:1013758116346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson GP, Paul EA, Harwood RR. Greenhouse gases in intensive agriculture: contributions of individual gases to the radiative forcing of the atmosphere. Science. 2000;289:1922–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao X, Wang SQ, Xing GX. Nitrification, acidification, and nitrogen leaching from subtropical cropland soils as affected by rice straw-based biochar: laboratory incubation and column leaching studies. J Soil Sediment. 2014;14:471–482. doi: 10.1007/s11368-013-0803-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ventura M, Sorrenti G, Panzacchi P, George E, Tonon G. Biochar reduces short-term nitrate leaching from a horizon in an apple orchard. J Environ Qual. 2013;42:76–82. doi: 10.2134/jeq2012.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biederman LA, Harpole WS. Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: a meta-analysis. Gcb Bioenergy. 2013;5:202–214. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glaser B, Lehmann J, Zech W. Ameliorating physical and chemical properties of highly weathered soils in the tropics with charcoal - a review. Biol Fert Soils. 2002;35:219–230. doi: 10.1007/s00374-002-0466-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang JY, Pan XJ, Liu YL, Zhang XL, Xiong ZQ. Effects of biochar amendment in two soils on greenhouse gas emissions and crop production. Plant Soil. 2012;360:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1250-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohanty SR, Bodelier PLE, Floris V, Conrad R. Differential effects of nitrogenous fertilizers on methane-consuming microbes in rice field and forest soils. Appl Environ Microb. 2006;72:1346–1354. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1346-1354.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, Y. S. et al. Simulated nitrogen deposition reduces CH4 uptake and increases N2O emission from a subtropical plantation forest soil in southern China. Plos One9, doi:ARTN e9357110.1371/journal.pone.0093571 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Scheutz C, Pedersen GB, Costa G, Kjeldsen P. Biodegradation of methane and halocarbons in simulated landfill biocover systems containing compost materials. J Environ Qual. 2009;38:1363–1371. doi: 10.2134/jeq2008.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spokas KA. Impact of biochar field aging on laboratory greenhouse gas production potentials. Gcb Bioenergy. 2013;5:165–176. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knoblauch C, Marifaat A-A, Haefele M. Biochar in rice-based system: Impact on carbon mineralization and trace gas emissions. Bioresource Technology. 2008;95:255–257. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lehmann J, et al. Biochar effects on soil biota - A review. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:1812–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amaral JA, Ren T, Knowles R. Atmospheric methane consumption by forest soils and extracted bacteria at different pH values. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64:2397–2402. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2397-2402.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clemens, J. & Wulf, S. Reduktion der ammoniakausgasung aus kofermentationssubstraten und gülle während der lagerung und ausbringung durch interne versaurung mit in NRW anfallenden organischen kohlenstofffraktionen. Bonn, Germany: Forschungsvorhaben im Auftrag des Ministeriums für Umwelt und Naturschutz, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, 41 (2005).

- 56.Van Zwieten L, et al. An incubation study investigating the mechanisms that impact N2O flux from soil following biochar application. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2014;191:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spokas KA, Baker JM, Reicosky DC. Ethylene: potential key for biochar amendment impacts. Plant Soil. 2010;333:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0359-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baggs EM. Soil microbial sources of nitrous oxide: recent advances in knowledge, emerging challenges and future direction. Curr Opin Env Sust. 2011;3:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2011.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh, B. P. & Cowie, A. L. Long-term influence of biochar on native organic carbon mineralization in a low-carbon clayey soil. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–9. doi:10.1038/srep03687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Yousaf BL, et al. Inverstigating the biochar effects on C-mineralization and sequestration of carbon in soil compared with conventional amendments using stable isotope (δ13C) approach. Gcb Bioenergy. 2016;1:208–11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.