Abstract

Household air pollution (HAP) and chronic HIV infection are each associated with significant respiratory morbidity. Little is known about relationships between HAP and respiratory symptoms among people living with HIV. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between cooking fuel type and chronic respiratory symptoms in study participants from the Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes Study.

Study participants were enrolled at the time of antiretroviral therapy initiation and seen quarterly from 2005 to 2014 for health-focused questionnaires, CD4 count and HIV viral load. We used multivariable logistic regression and generalised estimating equations, with each study visit as a unit of observation, to investigate relationships between cooking fuel type and chronic respiratory symptoms.

We observed an association between cooking with firewood (versus charcoal) and chronic cough among HIV-infected females in rural Uganda (adjusted OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.00–1.99; p=0.047). We did not observe an association between cooking fuel type and respiratory symptoms among males (adjusted OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.47–1.63; p=0.658).

Associations between cooking fuel and chronic cough in this HIV-infected cohort may be influenced by sex-based roles in meal preparation. This study raises important questions about relationships between household air pollution, HIV infection and respiratory morbidity.

Short abstract

This study raises important questions about relationships between air pollution, HIV and respiratory morbidity http://ow.ly/zjsJ30arkI0

Introduction

More than 4 million deaths were attributed to household air pollution (HAP) worldwide in 2012. HAP predominantly results from the burning of biomass fuel for cooking and heating. Biomass fuels (firewood, charcoal, animal dung and crop residues) are highly polluting fuels used by more than half the world's population. Exposure to biomass fuels increases risk of chronic respiratory symptoms, particularly among females in low-income settings [1].

Chronic HIV infection is also independently associated with increased risk of chronic respiratory symptoms [2–6]. HIV and HAP are each hypothesised to cause pulmonary morbidity through systemic inflammatory pathways [7, 8], yet little is known about relationships between HAP and pulmonary morbidity among people living with HIV. It is plausible, for example, that HAP causes disproportionate pulmonary morbidity among people living with HIV due to similar effects on systemic inflammation. We analysed data from the Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes Study (UARTO), a longitudinal cohort of HIV-infected persons taking antiretroviral therapy (ART), to estimate associations between HAP and respiratory symptoms among an HIV-infected population in Uganda.

Materials and methods

Adults aged >18 years were enrolled at the time of ART initiation during 2005–2014. Participants were seen quarterly to complete questionnaires and undergo phlebotomy for CD4 count and HIV-1 RNA viral load. At each visit, participants were asked about a history of cough or dyspnoea in the past 30 days. Those who reported cough were asked if the duration was >4 weeks. Participants who confirmed respiratory symptoms in the past 30 days were asked how bothersome each symptom was, on a four-point scale (“not at all”, “a little”, “moderately” and “a lot”). In addition, participants completed an annual questionnaire, in which they were asked “What is the main fuel used for cooking?”

We fit multivariable logistic regression models using generalised estimating equations and an exchangeable matrix structure with each study visit as a unit of observation to measure associations between respiratory symptoms and cooking fuel. Our outcomes of interest were 1) any self-reported cough or dyspnoea and 2) a self-reported cough of ≥4 weeks' duration (“chronic cough”). Our exposure of interest was self-reported cooking fuel type: firewood or charcoal (which were reported in 97% of study visits). Models were adjusted for known correlates of respiratory symptoms, including age, smoking status (current/former/never), occupation, household asset index, CD4 count and viral load. We explored prespecified interactions between cooking fuel type and sex because Ugandan females do most of the cooking and could have higher exposure to biomass fuels, and used postestimation margins to compare the adjusted proportion of participants who reported each outcome by cooking fuel type. We tested the significance of global categorical model coefficients (e.g. CD4 count strata) using a Wald test.

Data were analysed using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All study procedures were approved by Partners HealthCare (Boston, MA, USA) and the Mbarara University of Science and Technology (Mbarara, Uganda), and all participants gave written informed consent.

Results

Out of 762 participants enrolled in UARTO, 742 (97%) completed at least one questionnaire on respiratory symptoms and cooking fuel use. Eight (1%) had missing data for at least one covariate at each study visit and were excluded. Overall, 734 participants contributed 2757 study visits (median 20 visits) and were followed for a median (interquartile range (IQR)) 5 (2–7) years (table 1). At the time of study enrolment, 70% (n=511) were female, median (IQR) age was 34 (28–40) years, median (IQR) CD4 count was 167 (95–260) μL·L−1, 23% (n=172) had ever smoked and 58% (n=428) reported firewood as the primary cooking fuel.

TABLE 1.

Summary characteristics for participants at the enrolment study visit

| Total cohort | Males | Females | p-value# | |

| Subjects n | 734 | 223 | 511 | |

| Age years | 34 (28–40) | 37 (32–43) | 32 (27–38) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status¶ | <0.001 | |||

| Current | 90 (12) | 62 (28) | 28 (5) | |

| Former | 82 (11) | 44 (20) | 37 (7) | |

| Never | 562 (77) | 116 (52) | 446 (87) | |

| Household asset ownership index+ | ns | |||

| Lowest quartile | 235 (32) | 62 (28) | 173 (34) | |

| Second quartile | 173 (24) | 57 (26) | 116 (23) | |

| Third quartile | 177 (24) | 58 (26) | 119 (23) | |

| Highest quartile | 140 (19) | 42 (19) | 98 (19) | |

| High-risk occupation§ | 237 (32) | 117 (52) | 120 (23) | <0.001 |

| Cooking fuel type | 0.001 | |||

| Charcoal | 297 (40) | 70 (31) | 227 (44) | |

| Firewood | 428 (58) | 149 (67) | 279 (55) | |

| Self-reported pulmonary disease history | ||||

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 60 (8) | 26 (12) | 34 (7) | 0.02 |

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | 38 (5) | 14 (6) | 24 (5) | ns |

| Cryptococcal pneumonia | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (<1) | ns |

| CD4 count | ns | |||

| <100 cells·μL−1 | 198 (27) | 73 (33) | 125 (24) | |

| 100–349 cells·μL−1 | 441 (60) | 124 (56) | 317 (62) | |

| 350–499 cells·μL−1 | 59 (8) | 18 (8) | 41 (8) | |

| ≥500 cells·μL−1 | 34 (5) | 7 (3) | 27 (5) | |

| Viral load | 0.01 | |||

| ≤10 000 copies·mL−1 | 79 (11) | 14 (6) | 65 (13) | |

| >10 000 copies·mL−1 | 649 (88) | 206 (92) | 443 (87) | |

| Study visits per participant n | 20 (7–28) | 16 (7–28) | 21 (8–28) | ns |

| Observation time years | 5 (2–7) | 4 (2–7) | 5 (2–7) | ns |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. #: p-values for comparisons between sexes, calculated using t-test for normally distributed variables, Wilcoxon rank sum testing for non-normally distributed variables and Chi-squared testing for dichotomous and categorical variables; ¶: never-smokers defined as those who did not smoke prior to cohort enrolment and continued not to smoke; former smokers defined as those who smoked prior to cohort enrolment, but did not smoke throughout the duration of the study; current smokers defined as those who smoked at cohort enrolment and continued to smoke throughout the duration of the study; +: constructed following the method of Filmer and Pritchett [9], using the following binary indicator variables: home ownership; land ownership; livestock ownership; presence of the following items (yes/no) in the household: iron, stove, fridge, phone, motorcycle, clock, bed, sofa, bike, television, lantern, cupboard, shoes, car, radio, mattress or electricity; characteristics of the home: flushing toilet, cement wall, cement floor or piped water; §: includes farmer, cook, motorcyclist, brick worker, builder, carpenter, cattle keeper, dry cleaner and sand miner. ns: nonsignificant.

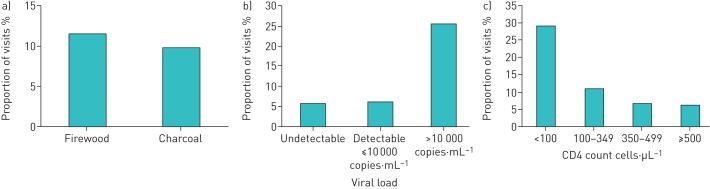

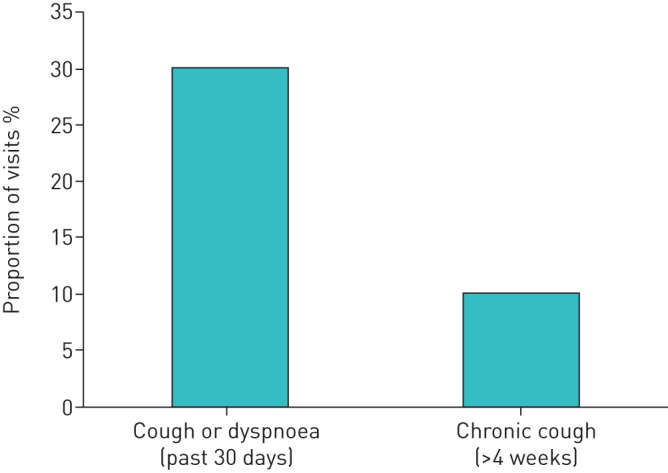

Respiratory symptoms were commonly reported during the observation period. Study participants reported cough or dyspnoea in the past 30 days or chronic cough at 30% (n=827) and 10% (n=287) of visits, respectively (figure 1). Among those who self-reported respiratory symptoms, 53% (n=200) of those reporting cough and 48% (n=92) of those reporting dyspnoea quantified the symptom burden as “a little”.

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of self-reported respiratory symptoms at study visits as a proportion of total study visits.

In multivariable models adjusted for age, occupation, household asset ownership index (a proxy for socioeconomic status), smoking status, cooking fuel type, CD4 count and viral load, cooking with firewood as compared to charcoal was associated with increased odds of chronic cough among females (adjusted OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.00–1.99; p=0.047). This corresponds to a 3.0% excess (95% CI 0.1–5.9%) in the proportion of visits when chronic cough was reported for those using firewood (12%) versus charcoal (9%). We found no relationships between respiratory symptoms and cooking fuel type among males (adjusted OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.47–1.63; p=0.658). In multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, occupation, smoking status and cooking fuel type, chronic cough was additionally associated with lower socioeconomic status (p=0.01), lower CD4 count (p<0.01) and increased HIV viral load (p<0.001) (table 2 and figure 2). Interaction effects between cooking fuel type and degree of immunosuppression (CD4 count and HIV-1 viral load) were not statistically significant (p>0.3 for all interaction terms).

TABLE 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) for predictors of cough of ≥4 weeks' duration

| Total cohort | Males | Females | |

| Observations n | 2751 | 778 | 1973 |

| Age | |||

| <30 years | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 30–39 years | 0.86 (0.61–1.21) | 0.74 (0.32–1.76) | 0.85 (0.59–1.24) |

| 40–49 years | 0.88 (0.59–1.33) | 0.82 (0.32–2.09) | 0.91 (0.58–1.43) |

| ≥50 years | 1.39 (0.80–2.41) | 2.78 (1.01–7.62) | 0.72 (0.32–1.62) |

| Female | 1.18 (0.83–1.69) | ||

| High-risk occupation# | 0.78 (0.57–1.06) | 0.72 (0.42–1.25) | 0.77 (0.53–1.13) |

| Household asset ownership index | |||

| Lowest quartile | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Second quartile | 0.96 (0.68–1.35) | 1.00 (0.50–2.01) | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) |

| Third quartile | 0.61 (0.42–0.88) | 0.47 (0.21–1.04) | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) |

| Highest quartile | 0.62 (0.42–0.91) | 0.55 (0.24–1.27) | 0.64 (0.41–1.01) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former | 0.95 (0.62–1.45) | 0.95 (0.49–1.86) | 0.96 (0.54–1.69) |

| Current | 1.11 (0.65–1.89) | 0.83 (0.39–1.79) | 1.75 (0.81–3.78) |

| CD4 count | |||

| <100 cells·µL−1 | 2.16 (1.24–3.77) | 3.20 (0.89–11.42) | 1.75 (0.92–3.32) |

| 100–349 cells·µL−1 | 1.20 (0.76–1.90) | 1.16 (0.36–3.73) | 1.21 (0.74–2.00) |

| 350–499 cells·µL−1 | 1.01 (0.61–1.68) | 1.40 (0.41–4.82) | 0.90 (0.52–1.58) |

| ≥500 cells·µL−1 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Viral load | |||

| Undetectable | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| ≤10 000 copies·mL−1 | 1.07 (0.69–1.67) | 0.33 (0.08–1.40) | 1.38 (0.85–2.22) |

| >10 000 copies·mL−1 | 4.59 (3.30–6.38) | 6.48 (3.26–12.89) | 4.37 (2.97–6.42) |

| Cooking source | |||

| Charcoal | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Firewood | 1.25 (0.93–1.69) | 0.90 (0.48–1.67) | 1.41 (1.00–1.99)¶ |

#: includes farmer, cook, motorcyclist, brick worker, builder, carpenter, cattle keeper, dry cleaner and sand miner; ¶: p=0.047; p-value for interaction between cooking source and sex p=0.21.

FIGURE 2.

a) Proportion of study visits with reported chronic cough among females, stratified by cooking fuel type; b) proportion of study visits with reported chronic cough stratified by viral load; c) proportion of study visits with reported chronic cough stratified by CD4 count.

Discussion

We identified an association between use of firewood for cooking (as compared to charcoal) and chronic cough among HIV-infected females in rural Uganda, adjusted for indices of HIV disease stage (CD4 count or viral load). To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the association between cooking fuel and respiratory symptoms in an HIV-infected cohort. The results of this study are consistent with published literature on the respiratory effects of HAP in the general population, which has been associated with chronic respiratory symptoms, impaired pulmonary function, respiratory infections and lung cancer in HIV-uninfected cohorts, particularly among females [10]. Furthermore, prior work has demonstrated that chronic cough poses a greater burden on health-related quality of life for females than males [11]. Although it is plausible that they are related, the consequences of HAP on respiratory symptoms should not necessarily be assumed to be similar between HIV-infected and uninfected populations. Either synergistic or attenuated effects of HAP on the pulmonary health of HIV-infected individuals can be postulated based on formative data in the field. For example, HAP and HIV each cause systemic inflammation [7, 8], which may result in an additive or multiplicative effect of HAP on respiratory pathology among HIV-infected individuals, compared to HIV-uninfected populations. Similarly, HIV-infected individuals are more susceptible to respiratory infections due to immune compromise, resulting in higher incidences of pulmonary tuberculosis, pneumocystis and bacterial pneumonias [12]. Thus, any incremental increases in respiratory symptom burden caused by HAP exposure among HIV-infected individuals must also take into account underlying lung disease and whether it may attenuate the absolute effects of HAP on lung health. By demonstrating a relationship between HAP and respiratory symptoms, our data provide a rationale for further quantifying these complex associations among HIV-infected populations.

While there are no comparable studies among HIV-infected populations in sub-Saharan Africa, two recent studies measured the odds of cough among biomass-exposed populations in Malawi [13] and Nigeria [14]. Similar to our work, both studies identify increased odds of cough among females cooking with firewood. Urban and rural Malawian females who cooked with firewood as compared to charcoal had >300% increased odds of cough, and rural Nigerian females cooking with firewood as compared to kerosene gas had >400% increased odds of cough. Neither study reported data on HIV prevalence. Two notable differences might explain the increased odds of cough noted in those studies compared to our work. Firstly, the Malawian study population was 42% peri-urban and focused on females with primary cooking responsibilities, each of which may have led to increased pollutant exposure among study participants. Secondly, the Nigerian study compared firewood to a clean-burning fuel, whereas we compared firewood to the only other fuel prevalent regionally: charcoal, a biomass fuel.

The elevated risk in models restricted to females, but not males, may be due to the role of females in cooking in the region [10]. The increased chronic cough risk among those using firewood versus charcoal may be related to airborne endotoxin inhalation [15], which is associated with chronic respiratory symptoms and accelerated pulmonary function decline [16].

Chronic respiratory symptoms, including cough and dyspnoea, are prevalent self-reported conditions in established HIV cohorts in high-income settings, with comparable proportions to those reported here [2, 4]. Markers of inadequate HIV viral control were associated with chronic cough in our cohort, in keeping with published literature in several large US-based HIV-infected cohorts that have shown lower CD4 count and higher HIV-1 viral load to be independent risk factors for chronic respiratory symptoms [2, 4, 6]. In addition, respiratory symptoms in these cohorts are associated with impaired pulmonary function, postulated to be a result of prior pulmonary opportunistic infections and/or chronic inflammation-associated obstructive lung disease. Our study was limited to an HIV-infected population, and we are therefore unable to assess the relative contribution of HIV infection per se to the chronic cough burden. Importantly, HAP and HIV are each associated with chronic respiratory symptoms, so an essential unanswered question raised by our work is whether there are interactive effects between HIV infection and HAP that exacerbate chronic respiratory disease risk.

We also identified an association between chronic cough and lower socioeconomic status, as measured by the household asset index [9]. Our results are in accordance with published literature on associations with chronic cough, in which lower socioeconomic status portends increased risk of chronic productive cough [17, 18] and chronic bronchitis [19–21].

The main strength of this analysis is the reliance on a large, longitudinal study of HIV-infected persons in rural Uganda with rare missing data or losses from observation. The results of our work can be applied to HIV-infected people living in environments with high biomass exposure.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, cooking fuel type and respiratory symptoms are self-reported and subject to misclassification. However, any misclassification is likely to be noninformative and bias towards the null. Secondly, we compare firewood to another biomass fuel source (charcoal), rather than a cleaner burning fuel. However, this probably underestimates any true association between biomass fuel exposure in general and chronic cough in this population. Furthermore, >80% of sub-Saharan Africa is exposed to biomass smoke [22]. Comparing the two regionally prevalent biomass sources more accurately reflects the local biomass exposure patterns, increases the generalisability of our results to the HIV-infected sub-Saharan African community and provides critical knowledge to inform risk-reduction practices while global access to cleaner energy sources is evolving. Thirdly, no data were collected on the quantity of cooking fuel used or the participant's role in cooking activities, and self-reported cooking fuel type is a blunt instrument for quantification of household air pollution exposure. We partially accounted for this with models stratified by sex to account for presumed increased exposure among females, but acknowledge that future studies that comprehensively quantify biomass and other environmental exposures are necessary. Lastly, pulmonary function testing was not performed in this cohort. This limits inferences between chronic respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function.

Conclusions

In summary, we describe an increased risk of chronic cough associated with firewood use among HIV-infected females in rural Uganda. The epidemics of household air pollution and HIV converge in sub-Saharan Africa, where chronic respiratory disease is a leading cause of death and disability [23]. Much chronic respiratory disease is preventable. Our results signal a need to pursue further investigations to elucidate the public health implications of relationships between HIV, biomass exposure and chronic respiratory disease.

Disclosures

J. Haberer 00094-2016_Haberer (1.2MB, pdf)

Footnotes

Support statement: This study was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants P30AI027763 and R01MH054907. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at openres.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, et al. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 823–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gingo MR, Balasubramani GK, Rice TB, et al. Pulmonary symptoms and diagnoses are associated with HIV in the MACS and WIHS cohorts. BMC Pulm Med 2014; 14: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung JM, Liu JC, Mtambo A, et al. The determinants of poor respiratory health status in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014; 28: 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George MP, Kannass M, Huang L, et al. Respiratory symptoms and airway obstruction in HIV-infected subjects in the HAART era. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onyedum CC, Chukwuka JC, Onwubere BJ, et al. Respiratory symptoms and ventilatory function tests in Nigerians with HIV infection. Afr Health Sci 2010; 10: 130–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz PT, Wewers MD, Pacht E, et al. Respiratory symptoms among HIV-seropositive individuals. Chest 2003; 123: 1977–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy A, Gong J, Thomas DC, et al. The cardiopulmonary effects of ambient air pollution and mechanistic pathways: a comparative hierarchical pathway analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9: e114913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzpatrick ME, Singh V, Bertolet M, et al. Relationships of pulmonary function, inflammation, and T-cell activation and senescence in an HIV-infected cohort. AIDS 2014; 28: 2505–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data – or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001; 38: 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortimer K, Gordon SB, Jindal SK, et al. Household air pollution is a major avoidable risk factor for cardiorespiratory disease. Chest 2012; 142: 1308–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French CT, Fletcher KE, Irwin RS. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients complaining of chronic cough. Chest 2004; 125: 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crothers K, Huang L, Goulet JL, et al. HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das I, Jagger P, Yeatts K. Biomass Cooking Fuels and Health Outcomes for Women in Malawi. Ecohealth 2017; 14: 7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desalu OO, Adekoya AO, Ampitan BA. Increased risk of respiratory symptoms and chronic bronchitis in women using biomass fuels in Nigeria. J Bras Pneumol 2010; 36: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semple S, Devakumar D, Fullerton DG, et al. Airborne endotoxin concentrations in homes burning biomass fuel. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 988–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang XR, Zhang HX, Sun BX, et al. A 20-year follow-up study on chronic respiratory effects of exposure to cotton dust. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedlund U, Eriksson K, Rönmark E. Socio-economic status is related to incidence of asthma and respiratory symptoms in adults. Eur Respir J 2006; 28: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerveri I, Accordini S, Corsico A, et al. Chronic cough and phlegm in young adults. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 413–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellison-Loschmann L, Sunyer J, Plana E, et al. Socioeconomic status, asthma and chronic bronchitis in a large community-based study. Eur Respir J 2007; 29: 897–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montnémery P, Bengtsson P, Elliot A, et al. Prevalence of obstructive lung diseases and respiratory symptoms in relation to living environment and socio-economic group. Respir Med 2001; 95: 744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menezes AM, Victora CG, Rigatto M. Prevalence and risk factors for chronic bronchitis in Pelotas, RS, Brazil: a population-based study. Thorax 1994; 49: 1217–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2016 Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/International Energy Agency, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferkol T, Schraufnagel D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

J. Haberer 00094-2016_Haberer (1.2MB, pdf)