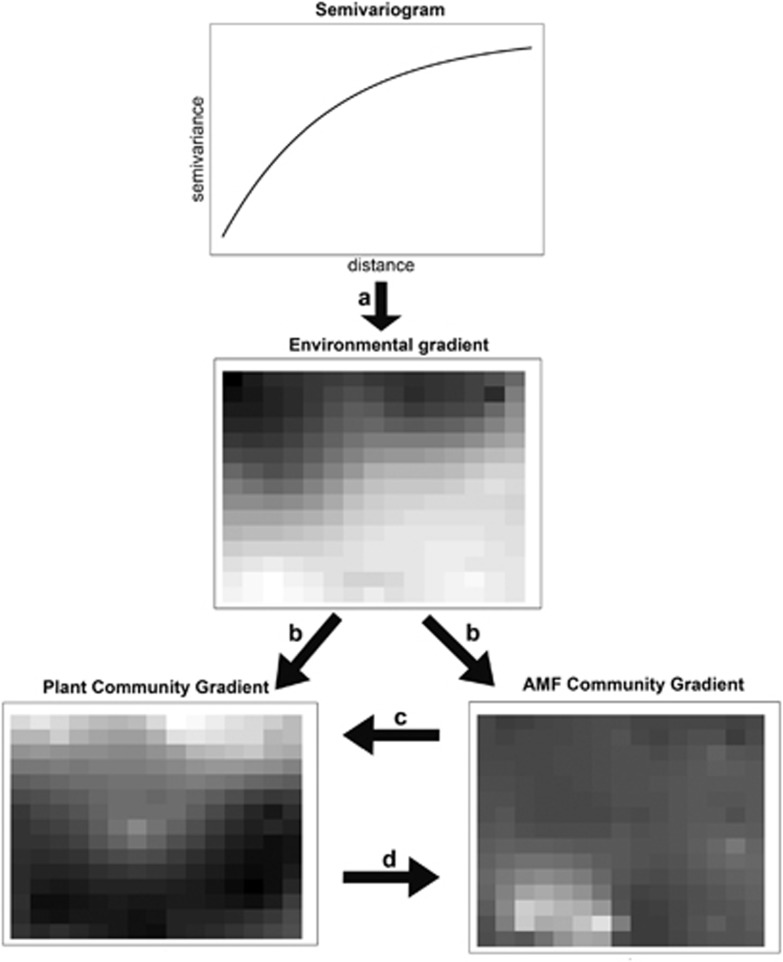

Figure 1.

Autocorrelation (Semivariogram) and trends in environmental variables create (arrow a) spatial structure and environmental gradients. Variation in the environment generates variation in plants and AMF (arrows b). AMF and plants can thus be structured by changes in habitat conditions, which can then simply lead to covariation between the two assemblages (Habitat hypothesis). Alternatively, AMF could either drive the plant assemblage (Driver hypothesis, arrow c) or be driven by the plant assemblage (Passenger hypothesis, arrow d). In all cases, the driving factors/assemblage (b–d) have a spatial structure that will be, at least partially, reflected by spatial structure in the driven assemblage. This spatial dependence calls for a spatially explicit approach to the testing of the three hypotheses. Spatial scale and successional stage have also been hypothesized to be the major factors in determining which among the Habitat, Driver and Passenger hypotheses apply to real systems. In addition to all these factors, AMF can also be structured by interactions within the assemblage, independently of plants, which has been hypothesized to happen at local scale and that could create very patchy distribution. All data are simulated.