Abstract

Background

Cardiac surgery is the most common setting for massive transfusion in medically advanced countries. Studies of massive transfusion following injury suggest that the ratios of administered plasma and platelets (PLT) to red blood cells (RBCs) affect mortality. The Red Cell Storage Duration Study (RECESS) was a large randomized trial of the effect of RBC storage duration in patients undergoing complex cardiac surgery. Data from that study was analyzed retrospectively to investigate the association between blood components ratios used in massively transfused patients and subsequent clinical outcomes.

Methods

Massive transfusion in subjects enrolled in RECESS was defined as those who had ≥6 RBC units or ≥8 total blood components. For plasma, high ratio was defined as ≥1 plasma unit:1 RBC unit. For PLT transfusion, high ratio was defined as ≥0.2 PLT doses:1 RBC unit; PLT dose was defined as one apheresis PLT or 5 whole blood PLT equivalents. The clinical outcomes analyzed were mortality and the change in the Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (Δ MODS) comparing the pre-operative score to the highest composite score through the earliest of death, discharge or day 7. These outcomes were compared between patients transfused with high and low ratios of plasma to RBCs, and also PLT to RBCs. Linear and Cox regression were used to explore relationships between predictors and continuous outcomes (ICU length of stay, 7-day ΔMODS, 28-day ΔMODS, hemoglobin, creatinine and total bilirubin) and time to event outcomes (all-cause mortality at postoperative day 2, 7, and 28), respectively.

Results

324 out of 1098 RECESS subjects met the definition of massive transfusion. In those receiving high plasma:RBC ratio, the mean (SE) 7-and 28-day ΔMODS was 1.24 (0.45) and 1.26 (0.56) points lower, (p=0.007 and p=0.024), respectively, than in patients receiving lower ratios. In patients receiving high PLT:RBC ratio, the mean (SE) 7- and 28-day ΔMODS were 1.55 (0.53) and 1.49 (0.65) points lower (p=0.004 and p=0.022) respectively. Subjects who received low ratio plasma:RBC transfusion had excess 7-day mortality compared to those who received high ratio (7.2% vs 1.7%, respectively, p=0.0318), which remained significant at 28 days (p=0.035). The ratio of PLT:RBCs was not associated with differences in mortality. The mean (SE) hemoglobin level on day 2 was 0.36 (0.15) g/L lower in the high plasma group for the entire cohort (p=0.016). It was also 0.62 (0.24) g/L lower in the high platelet group for those in the long blood storage group (p=0.009). However, these changes are unlikely to be clinically significant.

Conclusion

This analysis found that in complex cardiac surgery patients who received massive transfusion, there was an association between the composition of blood products used and clinical outcomes. Specifically, there was less organ dysfunction in those who received high ratio transfusions (plasma:RBC and PLT:RBCs), and lower mortality in those who received high ratio plasma:RBC transfusions.

Keywords: transfusion, cardiac surgery, massive transfusion, transfusion ratios

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac surgery is the most common setting for massive transfusion in developed countries.1 Each year, half a million people in the United States undergo surgery for coronary artery bypass grafting or valve replacement.2 Ninety percent of these patients receive fewer than 5 units of red blood cells (RBCs), and their mortality is generally less than 1%.3 However, for patients who receive more than 4 units of RBCs, mortality increases progressively with each additional unit of RBCs given. In a large single-center series of 15,000 consecutive patients, mortality was 1% among those receiving 5 units of RBCs, 3% with 6 units, 7% with 7 units, 18% with 8 or 9 units, and 30% with 10 units or more.3 Although there is not a universally accepted definition for massive transfusion, the transfusion of 5 or more units of RBC in 6 hours is one of the definitions which is becoming widely used.4, 5

Bleeding in cardiac surgery is associated with platelet dysfunction caused by contact with the non-biological cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) machine surfaces.6 Moreover, platelets tolerate the shear of blood pumping poorly, becoming partially activated and shedding the contents of their granules.7 During the course of the surgical procedure, the platelet count decreases as they are consumed in the circuit, and the function of the remaining platelets is impaired. As a result, platelet transfusions are commonly used to treat the platelet function defect and thrombocytopenia in patients undergoing CPB.8 A landmark randomized clinical trial studied different approaches for the administration of RBCs, platelets and plasma during massive hemorrhage as part of the resuscitation of trauma patients.9 The authors found that transfusing plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 ratio (plasma:platelets:RBCs) compared to transfusing at a 1:1:2 ratio led to more patients achieving hemostasis (86% vs 78%, P = 0.006). Moreover, fewer patients receiving 1:1:1 ratio died due to exsanguination at 24 hours (9.2%vs 14.6%in 1:1:2 group; difference, −5.4% [95%CI, −10.4%to−0.5%]; P = 0.03). The authors did not find significant differences in overall mortality at 24 h or at 30 days. We hypothesized that massively transfused cardiac surgery patients who received plasma and/or platelets at a high ratio to RBCs might have better clinical outcomes than those that did not.10

The Red Cell Storage Duration Study (RECESS) was a multi-center, prospective clinical trial in patients undergoing complex cardiac surgery via midline sternotomy who were selected to be at high risk of transfusion using a the “Transfusion Risk Understanding Scoring Tool” (TRUST), which was developed using multivariable logistic regression modeling techniques to determine independent variables that correlate with exposure to allogeneic blood transfusion.11 Patients with TRUST score ≥3, which predicts a 60% chance of transfusion, were randomized to receive red blood cells (RBCs) that had been stored either ≤10 days or ≥21 days, in order to evaluate the effect of the duration of RBC storage on postoperative changes in the Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (ΔMODS) and mortality (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT0099134).12 The study found that RBC storage duration was not associated with significant differences in ΔMODS at either 7 or 28 days, nor did it affect 7- or 28-day mortality. Adverse events also did not differ between the two arms, except for mild hyperbilirubinemia, which was more common in the subjects randomized to longer stored red cells.

To investigate whether massively transfused complex cardiac surgery patients who received blood product transfusions in a high ratio of plasma:RBC or platelet:RBC have improved organ function and decreased mortality, a subset of the RECESS study population was studied. The goal of this analysis of the RECESS study data was to determine if outcomes were different among subjects who received either a low ratio or a high ratio of platelet (PLT) or plasma in relation to RBCs units during massive transfusion after cardiac surgery, focusing separately on plasma units in ratio to RBC units (plasma:RBC ratio) and platelet doses in ratio to RBC units (platelet dose:RBC).13

METHODS

Subjects were enrolled to the RECESS study if they met the inclusion criteria: ≥12 years old, weighed ≥40 kg, and were scheduled for complex cardiac surgery via median sternotomy. Patients ≥18 years old were also required to have a TRUST score ≥ 3, indicating ≥ 60% probability of RBC transfusion.11 The study was approved by each participating center’s Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Participants were randomized to receive RBC units which had been stored ≤10 days, or RBC units stored ≥21 days, for all transfusions from randomization through post-operative day 28, hospital discharge, or death, whichever occurred first. Since most of the outcome measures in RECESS, including ΔMODS and mortality, were not different between the two study arms, we pooled the subjects from both arms for this study considering them to be at equivalent risk for any consequences of differences in the volumes of blood components they received. The MODS score is a validated scoring system for changes in organ function that incorporates mortality14. It has been used and validated in studies of patients with cardiovascular disease in the critical care setting15, 16. If subjects died, their MODS was assigned the maximum value of 24. Patients that died within 24 hours were excluded. Within the study, the date and time of the start of surgery and the issue of all blood products were recorded; the use of an intraoperative cell washer was not. Further details of the RECESS study approach, enrollment, and findings have been described.12, 17 The RECESS trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov number NCT00991341 on 10/0709.

Subjects who received 6 RBC units with a total of 8 total blood products were identified, and categorized into groups based on ratio of units of plasma and RBC (high plasma:RBC ratio, ≥ 1:1; or low plasma:RBC ratio, < 1:1) and the ratio of platelet doses and RBC units (high platelet:RBC ratio, ≥0.2:1; or low platelet:RBC ratio <0.2:1) that were transfused. A single unit of apheresis platelets was considered to be the equivalent of 5 units of whole blood-derived platelets (WBDP). Blood products were included if they were administered from the start time of the surgery until 24 hours later. Because there is no one universally accepted definition for massive transfusion, we included patients who had 6 or more RBC units or had 8 or more total blood components. The survival outcomes (all-cause mortality at postoperative day 2, 7, and 28) were compared between the two groups (defined by transfusion amounts) using Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier product-limit survival analysis with the logrank test. The continuous outcomes (ICU length of stay, 7-day ΔMODS and 28-day ΔMODS) were analyzed using linear regression. For each outcome, we first performed bivariate analyses. Any variable with a p-value < 0.2 was considered as a candidate for the final model; multivariable models were then constructed stepwise. Factors (key covariates) that might confound the relationship between plasma and platelet ratios and outcomes were added to the models to control for bias. These were baseline MODS, randomized treatment arm, cross-clamp time, cardiopulmonary bypass time, and the total number of blood products received in the 24-hour window; gender and baseline hemoglobin were not. Additionally, we analyzed post-operative day 0, 1 and 2 lab values: hemoglobin; creatinine (as a surrogate for renal impairment); and bilirubin using linear regression. Interactions between variables represented in the final regression models were also explored. The validity of the regression assumptions (proportional hazards for the survival models and linearity and homoscedasticity for the linear models) was assessed for each final model. None of the models presented violated any regression assumptions. Any p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using commercial statistical software (SAS version 9.3™, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 1098 RECESS subjects, 324 met the massive transfusion criteria by having received ≥6 units of RBCs and/or a total of at least 8 blood components (≥8 blood products). Subject demographics were not different between groups defined by transfusion ratios. However, the massively transfused subjects were more likely to be male, taller, have a lower baseline hemoglobin (Hb), and higher baseline bilirubin, creatinine and MODS scores than those who were not massively transfused (Supplemental Table 1). They also tended to have longer CPB time and aortic cross clamp time (ACC). Of the 324 subjects, 117 (36.1%) had a high ratio of plasma to RBC units, and 255 (78.7%) had a high ratio of platelet to RBC units (Table 1a, 1b).

Table 1a.

Baseline characteristics of Massive Transfused participants (Platelet Ratio)

|

Characteristic

N (row %) unless otherwise noted** |

Overall

(n=324) |

Platelet Ratio | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n=69) | High (n=255) | |||

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.4 (13.1) | 69.7 (12.2) | 71.8 (13.3) | 0.224 |

| Gender | 0.009 | |||

| Male | 178 (54.9%) | 28 (15.7%) | 150 (84.3%) | |

| Female | 146 (45.1%) | 41 (28.1%) | 105(71.9%) | |

| Race | 0.340 | |||

| Native American | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Asian | 11(3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| Black | 20 (6.2%) | 6 (30.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | |

| White | 287(88.6%) | 62(21.6%) | 225 (78.4%) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 5 (1.5%) | 1 (20.0%) | 4(80.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.015 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (1.9%) | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 309(95.4%) | 62(20.1%) | 247(79.9%) | |

| Refused | 9 (2.8%) | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (66.7%) | |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Baseline MODS, mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.8(0.9) | 0.823 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

1.2 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.2(0.6) | 0.290 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L), mean(SD) | 11.6 (1.7) | 10.9 (1.6) | 11.8(1.8) | <.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.913 |

| ICU admission | 0.187 | |||

| Yes | 14(4.3%) | 5(35.7%) | 9(64.3%) | |

| No | 310(95.7%) | 64(20.7%) | 246(79.4%) | |

| CBP duration, mean(SD) | 184.0 (82.7) | 177.8 (89.8) | 185.7 (80.8) | 0.482 |

| Duration of aortic cross clamp, mean(SD) |

126.2(61.9) | 124.5(58.1) | 126.6(63.0) | 0.798 |

| Trust score | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |

| 3 | 110(34.0%) | 24(21.8%) | 86(78.18%) | |

| 4 | 120(37.0%) | 18(15.0%) | 102(85.0%) | |

| 5 | 73(22.5%) | 19(26.0%) | 54(74.0%) | |

| 6 | 18(5.6%) | 7(38.9%) | 11(61.1%) | |

| 7 | 3 (0.9%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2(66.7%) | |

Fisher’s Exact p-values for categorical variables; t-test p-values for continuous variables

For the “overall” column, overall percentages are displayed; for the stratified column, row percentages are displayed.

Table 1b.

Baseline characteristics of Massive Transfused participants (Plasma Ratio)

|

Characteristic

N (row %) unless otherwise noted** |

Overall

(n=324) |

Platelet Ratio | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n=207) | High (n=117) | |||

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.4 ( 13.1) | 72.0 ( 12.9) | 70.3(13.3) | 0.255 |

| Gender | 0.027 | |||

| Male | 178 (54.9%) | 104 (58.4%) | 74 (41.6%) | |

| Female | 146 (45.1%) | 103 (70.6%) | 43 (29.5%) | |

| Race | 0.210 | |||

| Native American | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Asian | 11(3.4%) | 10(90.9%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Black | 20 (6.2%) | 13 (65.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | |

| White | 287(88.6%) | 181(63.07%) | 106(36.93%) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 5 (1.5%) | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.581 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (1.9%) | 5 (83.33%) | 1(16.67%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 309(95.4%) | 197(63.75%) | 112(36.25%) | |

| Refused | 9 (2.8%) | 5 (55.56%) | 4 (44.44%) | |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Baseline MODS, mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.8(0.8) | 0.664 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2(0.5) | 0.183 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L), mean(SD) | 11.6 (1.7) | 11.3 (1.7) | 12.2(1.6) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.9(0.6) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission | 0.582 | |||

| Yes | 14(4.3%) | 8 (57.1%) | 6 (42.9%) | |

| No | 310(95.7%) | 199(64.19%) | 111(35.8%) | |

| CBP duration, mean(SD) | 184.0 (82.7) | 178.7 (78.9) | 193.3 (88.6) | 0.131 |

| Duration of aortic cross clamp, mean(SD) |

126.2(61.9) | 122.3(56.2) | 132.9(70.5) | 0.172 |

| Trust score | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | |

| 3 | 110(34.0%) | 62(56.4%) | 48(43.6%) | |

| 4 | 120(37.0%) | 82(68.3%) | 38(31.7%) | |

| 5 | 73(22.5%) | 52(71.2%) | 21(28.8%) | |

| 6 | 18(5.6%) | 10(55.6%) | 8(44.4%) | |

| 7 | 3 (0.9%) | 1(33.3%) | 2(66.7%) | |

Fisher’s Exact p-values for categorical variables; t-test p-values for continuous variables

For the “overall” column, overall percentages are displayed; for the stratified column, row percentages are displayed.

All of the 324 subjects survived at least 24 hours. The 7-day ΔMODS was on average lower (more favorable) by 1.55 points (SE=0.53, p=0.004) for high platelet:RBC transfusion ratio, compared to low platelet:RBC ratio, after adjusting for plasma:RBC transfusion ratio, baseline MODS, the total number of blood products received in the 24-hour window, and randomized treatment arm (Table 2). The subjects receiving a high plasma:RBC transfusion ratio also had a 1.24 point lower 7-day ΔMODS compared to the low plasma:RBC ratio (SE=0.45, p=0.007), independent of the effect of platelet:RBC transfusion ratio and baseline MODS, the total number of blood products received in the 24-hour window, and randomized treatment arm. The subjects who received a high platelet:RBC transfusion ratio also had a 28-day ΔMODS score that was 1.49 points lower compared to low platelet:RBC ratio (SE=0.65, p=0.022). The subjects who were transfused with a high plasma:RBC ratio had a 1.26 lower 28-day ΔMODS score compared to low platelet:RBC ratio (SE=0.56, p=0.024). The interactions between patients who received both plasma:RBC and PLT:RBC in high or low ratios were explored and not found to be significant.

Table 2.

Linear Regression results for 7 and 28-day ΔMODS in massively transfused cardiac surgery patients.

| Outcomes and predictors | Beta (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| 7-Day ΔMODS | ||

| High plasma:RBC | −1.24 (0.45) | 0.007 |

| High platelet:RBC | −1.55 (0.53) | 0.004 |

| Treatment arm | −0.11 (0.43) | 0.791 |

| 28-Day ΔMODS | ||

| High plasma:RBC | −1.26 (0.56) | 0.024 |

| High platelet:RBC | −1.49 (0.65) | 0.022 |

| Treatment arm | −0.74 (0.53) | 0.163 |

Models control for CPB and ACC duration. Reference groups for plasma:RBC, platelet:RBC, and treatment arm are ‘Low plasma:RBC’, ‘Low platelet:RBC’, and ‘RBC storage ≥21 days’, respectively.

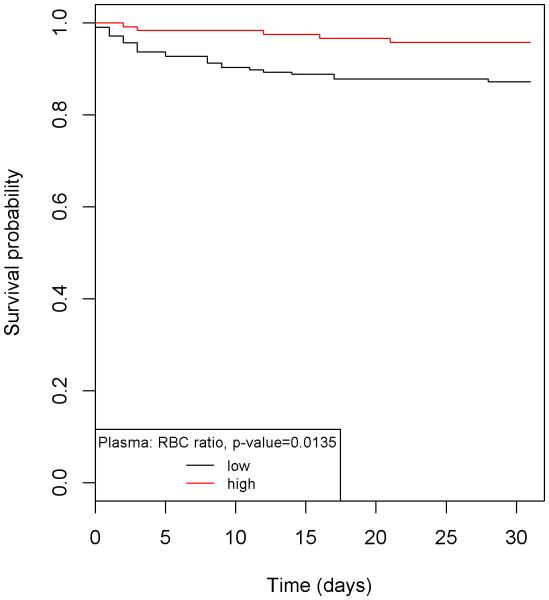

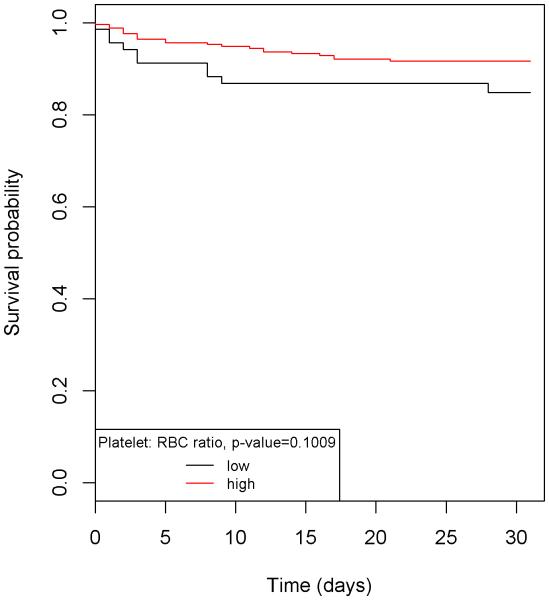

Cox proportional hazards regression models, controlling for baseline MODS, ACC, CPB, and total number of blood products received, showed high plasma:RBC ratio transfusion was associated with a lower risk of death; hazard ratio of 0.23 (95% CI 0.05, 1.01, p=0.052) through 7 days and a hazard ratio of 0.36 (95% CI 0.14, 0.97, p=0.042) through 28 days. This association was not seen with the high platelet:RBC ratio at either time point. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed consistently better survival in the high plasma:RBC ratio subjects (Figure 1). Deaths began to accrue on day one and continued to accrue throughout the post-operative period, but the majority of all excess deaths had occurred by day 10. By the end of 28 days of follow-up, there was a 3-fold increased survival benefit in the high plasma:RBC ratio (Log rank, p=0.0135) (Table 3). Analyses of hospital and ICU discharge by day 31 did not find an association with either platelet:RBC or plasma:RBC ratios (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for all-cause mortality through day 28, stratified by (a) plasma:RBC ratio and (b) platelet:RBC ratio. Note that the majority of the excess mortality occurs early in post-operative month.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression results for time-to-death.

| Outcomes and predictors | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| 7-day all-cause mortality | ||

| High plasma:RBC | 0.23 (0.05, 1.01) | 0.052 |

| High platelet:RBC | 0.51 (0.18, 1.42) | 0.197 |

| Treatment arm | 2.02 (0.73, 5.59) | 0.174 |

| 28-day all-cause mortality | ||

| High plasma:RBC | 0.36 (0.14, 0.97) | 0.042 |

| High platelet:RBC | 0.58 (0.26, 1.31) | 0.193 |

| Treatment arm | 1.00 (0.47, 2.13) | 0.996 |

All models were adjusted for baseline MODS, total number of blood products received, ACC and CPB.

Reference groups for plasma:RBC, platelet:RBC, and treatment arm are ‘Low plasma:RBC’, ‘Low platelet:RBC’, and ‘RBC storage ≥21 days’, respectively.

The only laboratory value to be statistically significantly associated with the ratios was hemoglobin. Patients with high plasma:RBC tended to have values of hemoglobin on day 2 that were 0.36 g/L lower than those with low plasma:RBC ratios (p=0.016, Table 4). Patients with high platelet: RBC in the longer blood storage arm tended to have values of hemoglobin on day 2 that were 0.62 g/L lower than those with low platelet:RBC ratios (p=0.009). This hemoglobin difference is not likely to be of clinical significance and was not associated with any excess mortality either in the original trial or in our reanalysis.

Table 4.

Comparison of laboratory parameters for subjects receiving massive transfusion that were high plasma or high platelet ratios, compared to those receiving low plasma or low platelet ratios, respectively.

| Post-op day 2 lab values | Beta (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||

| High plasma:RBC | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.825 |

| High platelet:RBC | −0.11 (0.07) | 0.090 |

| Treatment arm | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.725 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | ||

| High plasma:RBC | −0.36 (0.15) | 0.016 |

| High platelet:RBC | −0.62 (0.24) | 0.009 |

| Treatment arm | −0.54 (0.30) | 0.071 |

| Platelet:RBC * treatment arm | 0.61 (0.33) | 0.069 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||

| High plasma:RBC | 0.02 (0.18) | 0.908 |

| High platelet:RBC | −0.25 (0.21) | 0.249 |

| Treatment arm | −0.48 (0.18) | 0.007 |

All models were adjusted for pre-op levels of the respective lab, ACC, CPB and total number of blood products received. Reference groups for plasma:RBC, platelet:RBC, and treatment arm are ‘Low plasma:RBC’, ‘Low platelet:RBC’, and ‘RBC storage ≥21 days’, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis, high-transfusion-risk cardiac surgery patients who were part of a randomized prospective trial and received ≥6 units of RBCs or ≥8 total blood components appeared to have a survival benefit when receiving plasma in a high ratio to RBCs. This observation is consistent with retrospective and prospective studies in trauma patients, which suggest that the transfusion of high ratio plasma and PLTS during resuscitation decreases the risk of hemorrhagic death.9, 18, 19 Because these associations between ratios and outcomes in cardiac surgery patients were derived from a retrospective analysis, they must be considered to be hypothesis generating, and will require further prospective studies to confirm them and before considering any practice changes.

Recent analyses in trauma and non-trauma settings have focused on survival following massive transfusion. In RECESS, there were 52 deaths; 31(9.5%) in our massively transfused group. This is consistent with the survival rates reported by Dzik et al1 among non-trauma patients undergoing massive transfusion in different clinical settings. In this study, 22% of patients who received ≥20 RBC units in 48 hours were cardiac and vascular surgery patients. They had an overall survival of 71% (5-day) and 60% (30-day). The ratio of plasma and platelets to RBCs was noted in this study, but the association with patient survival was not reported.

In our study, we found that a high PLT transfusion ratio was associated with a small reduction in MODS. It is not clear whether the MODS is a reliable predictor of mortality in the massively transfused patients, but if it is, then the high frequency of platelet transfusions in this population may contribute to unexpected increased survival in that analysis.

There are several limitations with this analysis: it is retrospective, the examined population is small, and the statistical power of the conclusion is weak; additional sub group analyses were not undertaken given the relatively small sample size. The subjects in this analysis were a sub-set of the RECESS study population who were entered into RECESS based on a predicted higher risk of RBC transfusion i.e. by having a TRUST score that predicted a 60% chance of transfusion. The TRUST score was developed using robust statistical modeling of over 15,000 subjects and found that low hemoglobin, female gender, low body weight, greater age, elevated creatinine, and type of surgery (repeat sternotomy, non-elective, non-isolated procedure), were risk factors for RBC transfusion (i.e. favors a higher score). These selection criteria weights these characteristics in this analysis. Additionally, the RECESS data set did not include center- specific transfusion policies, and so this could not be compared in this exploratory analysis. The center-to-center variation was presumably minimized by the fact that randomization was balanced by center. Surgeon skill (or a surrogate such as years of experience) was not included in the original RECESS dataset, so it was not able to be incorporated into this analysis. Despite these limitations, it is the largest population of massively transfused cardiac surgery patients in which the association of blood component ratios with clinical outcomes has been investigated.

These data suggest that transfusion of higher ratios of plasma to RBCs in massively transfused cardiac surgery patients was associated with improved outcomes. Further studies are needed to gain a deeper understanding about the impact of transfusion ratios in other cardiac surgery patient populations that are at high risk for transfusion. In the PROPPR trial, giving plasma at a 1:1 ratio with RBCs was not associated with any excess in a number of complications, more patients achieved hemostasis, and hemorrhage stopped sooner for patients at risk of hemorrhagic death. Further study on the best approach to massive transfusions in cardiac surgery is warranted to deepen our knowledge and improve patient care.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Joe Gu for his assistance with the data analysis.

The authors have no financial conflict of interest with the contents of this study.

SUPPORT

Transfusion Medicine and Hemostasis Clinical Trials Network (TMHCTN) supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (clinicaltrials.gov # NCT00991341)

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have no financial conflict of interest with the contents of this study.

- Meghan Delaney: Conceived of project idea, designed study, interpreted results, wrote paper, revised paper, edited paper, approved final paper for submission, submitted paper

- Paul C. Stark: Formulated and performed analyses, interpreted results, revised paper, edited paper, submitted paper, approved final paper for submission

- Minhyung Suh: Formulated and performed analyses, revised paper, approved final paper for submission

- Darrell J.Triulzi: Supported project design development, interpreted results, revised paper, edited paper, approved final paper for submission

- John R. Hess: Supported project design development, interpreted results, revised paper, edited paper, approved final paper for submission

- Marie Steiner: Lead primary RECESS study, Supported project design development, interpreted results, revised paper, edited paper, approved final paper for submission

- Christopher P. Stowell: Helped design study, interpreted results, revised paper, edited paper, approved final paper for submission

- Steven R. Sloan: Helped design study, interpreted results, revised results, revised paper, edited paper, approved final paper for submission

HUMAN SUBJECTS OVERSIGHT: Each of the participating institutions in the RECESS study obtained human subjects approval at each center.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Dzik WS, Ziman A, Cohen C, et al. Survival after ultramassive transfusion: a review of 1360 cases. Transfusion. 2016;56:558–563. doi: 10.1111/trf.13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs JP, Shahian DM, Prager RL, et al. Introduction to the STS National Database Series: Outcomes Analysis, Quality Improvement, and Patient Safety. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015;100:1992–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koch CG, Li L, Duncan AI, et al. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1608–1616. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217920.48559.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanworth SJ, Morris TP, Gaarder C, et al. Reappraising the concept of massive transfusion in trauma. Critical care (London, England) 2010;14:R239. doi: 10.1186/cc9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zatta AJ, McQuilten ZK, Mitra B, et al. Elucidating the clinical characteristics of patients captured using different definitions of massive transfusion. Vox sanguinis. 2014;107:60–70. doi: 10.1111/vox.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kehara H, Takano T, Ohashi N, Terasaki T, Amano J. Platelet function during cardiopulmonary bypass using multiple electrode aggregometry: comparison of centrifugal and roller pumps. Artif Organs. 2014;38:924–930. doi: 10.1111/aor.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harker LA, Malpass TW, Branson HE, Hessel EA, 2nd, Slichter SJ. Mechanism of abnormal bleeding in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass: acquired transient platelet dysfunction associated with selective alpha-granule release. Blood. 1980;56:824–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perek B, Stefaniak S, Komosa A, Perek A, Katynska I, Jemielity M. Routine transfusion of platelet concentrates effectively reduces reoperation rate for bleeding and pericardial effusion after elective operations for ascending aortic aneurysm. Platelets. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2016.1184748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;313:471–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sniecinski RM, Levy JH. Bleeding and management of coagulopathy. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2011;142:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alghamdi AA, Davis A, Brister S, Corey P, Logan A. Development and validation of Transfusion Risk Understanding Scoring Tool (TRUST) to stratify cardiac surgery patients according to their blood transfusion needs. Transfusion. 2006;46:1120–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner ME, Ness PM, Assmann SF, et al. Effects of red-cell storage duration on patients undergoing cardiac surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:1419–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holcomb JB, Jenkins D, Rhee P, et al. Damage control resuscitation: directly addressing the early coagulopathy of trauma. The Journal of trauma. 2007;62:307–310. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180324124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1638–1652. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert PC, Yetisir E, Martin C, et al. Is a low transfusion threshold safe in critically ill patients with cardiovascular diseases? Crit Care Med. 2001;29:227–234. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley TA, Gomersall CD, Ramsay SJ. Validation of the multiple organ dysfunction (MOD) score in critically ill medical and surgical patients. Intensive care medicine. 2003;29:2216–2222. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner ME, Assmann SF, Levy JH, et al. Addressing the question of the effect of RBC storage on clinical outcomes: the Red Cell Storage Duration Study (RECESS) (Section 7) Transfusion and apheresis science : official journal of the World Apheresis Association : official journal of the European Society for Haemapheresis. 2010;43:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotton BA, Reddy N, Hatch QM, et al. Damage control resuscitation is associated with a reduction in resuscitation volumes and improvement in survival in 390 damage control laparotomy patients. Annals of surgery. 2011;254:598–605. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318230089e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holcomb JB, del Junco DJ, Fox EE, et al. The prospective, observational, multicenter, major trauma transfusion (PROMMTT) study: comparative effectiveness of a time-varying treatment with competing risks. JAMA surgery. 2013;148:127–136. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.