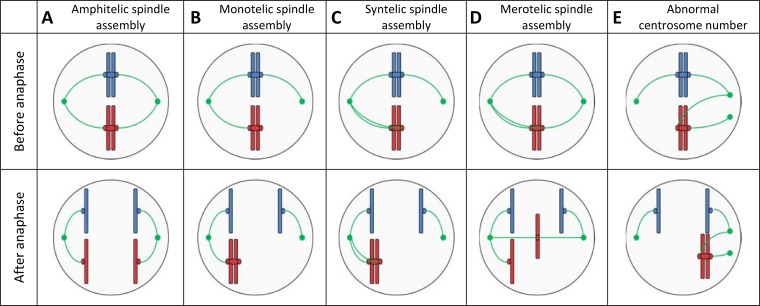

FIG 2.

Schematic representation of chromosome segregation and of the common mechanisms leading to chromosome missegregation. Two chromatids of two different chromosomes are shown in red and blue, with their centromeres and kinetochores. In green, the centrosomes are shown with the assembled microtubule attached to the kinetochores of the chromatids. For each case, the microtubule-kinetochore assembly is shown before and after the anaphase. (A) Correct chromosome segregation is achieved by amphitelic spindle assembly, where microtubules connect each chromatid to a different centrosome, resulting in separation to opposite cellular poles during anaphase and maintaining a stable karyotype in the daughter cells (45). (B and C) If only one of the chromatids is attached to a centrosome or both chromatids are attached to the same kinetochore, referred to as monotely and syntely, respectively, proceeding to anaphase would result in the missegregation of both chromatids to that centrosome. However, monotelic and syntelic spindle assemblies are detected at the spindle assembly checkpoint and therefore rarely cause chromosome missegregation. (D) In the case of a merotelic spindle assembly, a chromatid is attached to both centrosomes and, as a result, cannot migrate to a cellular pole. The resulting random segregation of the lagging chromosome can cause missegregation, damage, and micronucleus formation (158). (E) When more than two centrosomes are formed, random attachment of chromatids can result in chromosome missegregation due to chromosome lagging or unequal chromosome segregation (159).