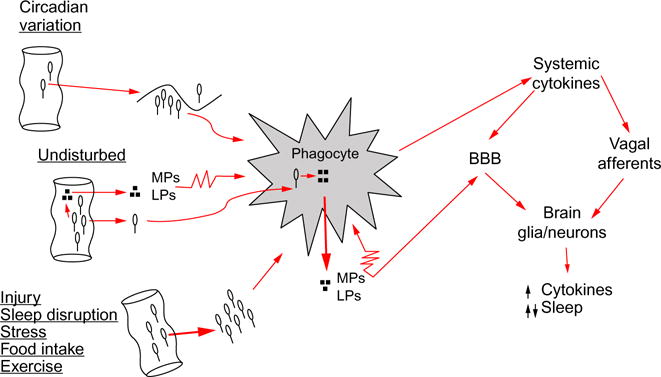

Fig. 1.

Pathway for intestinal bacteria to affect sleep. From left to right: intestinal bacteria, and/or bacteria cell wall degradation products, such as muramyl peptides (MPs) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), translocate across the intestinal epithelial barrier. Sleep loss and several conditions that affect sleep, e.g., injury, food intake, stress, circadian rhythm, and exercise, affect bacteria translocation. Bacteria are engulfed by phagocytes, such as macrophages or neutrophils, and digested; digest products (e.g., MPs, LPS) are released into the surrounding intercellular fluid. MPs and LPS in turn activate phagocytes (illustrated by the jagged cell membrane) that then release cytokines such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. Systemic cytokines access the brain by at least two routes. Cytokines can signal the brain via vagus nerve afferents whose action potentials induce further cytokine production in the brain by glia and neurons. Cytokines can also cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) to induce their own and other cytokine productions. Brain cytokines at low concentrations enhance sleep, while at high concentrations fragment sleep. Other microbes, e.g., viruses, and their components also enhance cytokine production via endogenous receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns, e.g., Toll-like receptors, to affect sleep (not illustrated).