Abstract

Release of arachidonic acid (AA) by cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), followed by metabolism through cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH), results in the formation of the eicosanoids 11-oxo- and 15-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid (oxo-ETE). Both 11-oxo- and 15-oxo-ETE have been identified in human biospecimens but their function and further metabolism is poorly described. The oxo-ETEs contain an α,β-unsaturated ketone and a free carbocyclic acid, and thus may form Michael adducts with a nucleophile or a thioester with the free thiol of Coenzyme A (CoA). To examine the potential for eicosanoid-CoA formation, which has not previously been a metabolic route examined for this class of lipids, we applied a semi-targeted neutral loss scanning approach following arachidonic acid treatment in cell culture, and detected inducible long-chain acyl-CoAs including a predominant AA-CoA peak. Interestingly, a series of AA-inducible acyl-CoAs at lower abundance but higher mass, likely corresponding to eicosanoid metabolites, was detected. Using a targeted LC-MS/MS approach we detected the formation of CoA thioesters of both 11-oxo- and 15-oxo-ETE and monitored the kinetics of their formation. Subsequently, we demonstrated that these acyl-CoA species undergo up to four double bond reductions. We confirmed the generation of 15-oxo-ETE-CoA in human platelets via LC-high resolution MS. Acyl-CoA thioesters of eicosanoids may provide a route to generate reducing equivalents, substrates for fatty acid oxidation, and substrates for acyl-transferases through cPLA2-dependent eicosanoid metabolism outside of the signaling contexts traditionally ascribed to eicosanoid metabolites.

Supplementary keywords: Eicosanoids, PGDH, KETE, LC-MS, coenzyme A, metabolism, LoVo

Introduction

Cyclooxygenases (COXs) are major enzymes responsible for the generation of bioactive lipids from the preferred precursor arachidonic acid (AA) (1). The AA oxidation product 11-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid (11-oxo-ETE) is generated by the sequential action of COXs, peroxidases, and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) on free AA (2). The known intermediates of this pathway are the unstable 11-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (11-HPETE) and the stable product 11-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (11-HETE) (3). 15-oxo-ETE can be generated by a COX/15-PGDH pathway from free AA or a 15-lipoxygenase (LOX) /15-PGDH or 12/15-LOX/15-PGDH pathway from free or esterified AA (4, 5). In multiple cancers and inflammatory conditions, COX-2 and 15-PGDH are counter-regulated, whereby COX-2 expression is increased and 15-PGDH levels are reduced (6–8). Furthermore, the expanding involvement of eicosanoids as part of oxidized phospholipids in inflammation, and atherosclerosis, once again warrants interest in the metabolism of oxidized lipids beyond established roles as signaling mediators (9).

Eicosanoid signaling is responsible for a vast array of cellular responses through families of G- protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (10). Evidence for non-GPCR mediated signaling exists (3–8), but is still controversial for some mediators (11). Electrophilic α,β-unsaturated ketone containing fatty acids derived from ω-6 and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and redox signaling properties (12–15). Descriptions of the formation of polar lipids composed of glycerol and ethanolamine head groups with eicosanoid acyl-chains (16), was followed by identification of other polar lipids with common head groups but also with acyl-chains derived from eicosanoids (9, 17). Recent work has also demonstrated cPLA2-dependent bioenergetic metabolism is required for platelet function (18). These lines of evidence suggest other, previously under-appreciated functions of eicosanoid metabolism outside of direct signaling processes. These studies also suggest, but did not examine, the existence of intermediates linking bioenergetic metabolism, especially β-oxidation, as well as the existence of eicosanoid substrates for acyl-transferases that can generate polar lipids with eicosanoid acyl-groups. Acyl-Coenzyme A thioesters are capable of performing both of these biochemical roles as ubiquitous, conserved, and localized substrates for both bioenergetics processes and synthetic pathways including those catalyzed by acyl-transferase enzymes. However, relatively little is known about the further metabolism of eicosanoids via acyl-CoA intermediates. Thus, this study was designed to determine the existence of these putative intermediates using oxo-eicosanoids for which no other function is currently described. We employed a COX-2/15-PGDH stably expressing human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (LoVo) that was used in previous studies of 11-oxo- and 15-oxo-ETE metabolism (2). Specifically, we investigated the CoA thioester formation of 11-oxo- and 15-oxo-ETE using untargeted and targeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) approaches, with confirmation in human platelets using LC-high resolution MS (LC-HRMS)

Materials and Methods

Reagents

11-oxoeicosatetranoic acid (11-oxo-ETE), 15-oxoeicosatetranoic acid (15-oxo-ETE), 11-oxo-eicosatetranoic acid methyl ester (11-oxo-ETE-ME), 15-oxo-eicosatetranoic acid methyl ester (15-oxo-ETE-ME) and the [13C20]-labeled 15-oxo-ETE internal standard were synthesized in-house as previously reported (2). [13C3 15N1]-Arachidonoyl-CoA used as an internal standard was synthesized as previously reported (19). Peroxide-free arachidonic acid (AA) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). 5-sulfosalicilic acid (SSA), ammonium formate, glacial acetic acid, 2-mercaptoethanol (BME), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HPLC grade chloroform as well as Optima LC-MS grade methanol, acetonitrile, water, isopropanol, ammonium acetate, and formic acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). 2-(2-pyridyl) ethyl functionalized silica gel (100 mg/mL) solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridges were obtained from Supelco Analytical (Bellefonte, PA). Streptomycin and penicillin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Gemini Bioproducts (West Sacramento, CA). Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (LoVo and HCA-7) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA).

Acyl-CoA analysis

Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (LoVo) were grown to 80% confluence in F-12K media with 2% FBS and 100,000 units/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin. Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (HCA-7) were grown to 80% confluence in DMEM/F12 media with 2% FBS and 100,000 units/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin. Cells were treated with stock solutions of eicosanoids in DMSO and final concentration was always kept under 0.1% of DMSO in the media. For platelet experiments, 1 mL of expired platelet concentrate from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Blood Bank was washed and treated with vehicle control (0.25% DMSO), 10 μM 15-oxo-ETE, or 50 μM arachidonic acid in Tyrode’s buffer containing 5 mM glucose as previously described(20). After 1 hour, the platelets were extracted as below, and analyzed by LC-HRMS as previously described(21).

Extraction and analysis were performed as previously described (19, 22). Briefly, cells were lifted with a cell scraper, and the resulting suspension was centrifuged at 500 × g at 4°C. For the time course experiments, cells were spiked with the [13C3 15N1]-arachidonoyl-CoA. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was suspended in 750 μL of 3:1 acetonitrile:isopropanol (ACN:IPA). The suspension was then sonicated with a probe tip sonicator (Fisher) to disrupt the cellular membranes. 250 μL of 100 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.7) was added, the suspension was vortexed, and then centrifuged at 16000 × g at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a glass tube and acidified with 125 μL glacial acetic acid for solid phase extraction. 100 mg 2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl-functionalized silica gel solid phase extraction columns (Sigma) were equilibrated with 1 mL 9:3:4:4 ACN:IPA:H2O:acetic acid. Supernatants were transferred to the column and filtrated under low vacuum. The columns were washed two times with 1 mL of the 9:3:4:4 mixture. The columns were eluted two times with 500 μL 4:1 methanol:250 mM ammonium formate into glass tubes. Filtrate was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen gas. The dry samples were dissolved in 50 μL of 70:30 water:acetonitrile with 5% SSA (w/v) and transferred into HPLC vials.

Liquid chromatography- Mass spectrometry

Chromatographic separation was performed using a reversed phase Waters XBridge BEH130 C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm pore size) on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system using a three solvent system as previously described (23): (A) 5 mM ammonium acetate in water, (B) 5 mM ammonium acetate in 95/5 acetonitrile/water (v/v), and (C) 80/20/0.1 (v/v/v) acetonitrile/water/formic acid, with a constant flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Solvent C was used after analysis to wash the column. The gradient was as follows: 2% B at 0 min, 2% B at 1.5 min, 20% B at 5 min, 100% B at 5.5 min, 100% B at 13.5 min, 100% C at 14 min, 100% C at 19 min, 2% B at 20 min and 2% B at 25 min. The column effluent was diverted to waste before 8 min and after 18 min. For targeted acyl-CoA analysis, samples were maintained at 4°C in a Leap CTC autosampler (CTC Analytics, Switzerland) during sample batch runs. 10 μL injections were used for LC-MS analysis. The LC was coupled to a API 4000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode and analyzed using Analyst software as previously described (24). The mass spectrometer operating conditions were as follows: ion spray voltage (5.0 kV), compressed air as curtain gas (15 psi) and nitrogen as nebulizing gas (8 psi), heater (15 psi), and collision-induced dissociation (CID) gas (5 psi). The ESI probe temperature was 450°C, the declustering potential was 105 V, the entrance potential was 10 V, the collision energy was 45 eV, and the collision exit potential was 15 V. CoA thioesters were screened using a neutral loss of 507, then monitored using SRM (selected reaction monitoring mode) as previously published (19). For LC-HRMS experiments, a Ultimate 3000 UHPLC coupled to a Thermo QExactive Plus operating with XCalibur (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA) as previously described was used(21). Shift in retention times between the two systems is due to differences in the LC tubing length and injector cycle.

Results

Untargeted acyl-CoA analysis reveals thioester formation and saturation

Using a previously described method (19) for analysis of acyl-CoA thioesters, we investigated the formation of an oxo-ETE-coenzyme A thioester, as had been described for other oxidized fatty acids (25). A proof-of-principle experiment was conducted using LoVo cells treated with DMSO vehicle control or 25 μM AA for 1 hour (Fig. 1). During ESI-MS, acyl-CoAs present a distinctive neutral loss of 507 amu as utilized above, corresponding to the loss of the CoA moiety by cleavage at the high energy phosphate bond (Fig 2). LC-MS/MS experiments using this stereotypical neutral loss of 507 Da corresponding to acyl-CoAs revealed the induction of acyl-CoA species. Fig.1A shows the DMSO control cells where the most abundant peaks were m/z 746, 810 and 838 corresponding to the “common” thioesters, CoA-SH, acetyl-CoA and butyryl-CoA respectively. In Fig. 1B a strong peak at m/z 1054, likely corresponding to arachidonoyl-CoA, was induced after AA treatment. This corresponds to the authentic spectra of archidonoyl-CoA and a stable isotope analog from the previously validated method (19). Interestingly, a peak at m/z 1068 was also observed, which would correspond to an oxo-ETE-CoA thioester (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1. Neutral loss of 507 Da scans show inducible acyl-CoA species.

Neutral loss scans of 507 Da of acyl-CoA extract from (A) DMSO (B) 25 μM AA treated LoVo cells.

Fig 2. Structure and metabolic pathways of oxo-ETE-CoA metabolism. (A) Chemical structures of 15-oxo-ETE-CoA and 11-oxo-ETE-CoA. (B) De-esterification of the methyl ester of 11-oxo-ETE (11-oxo-ETE-ME) was required before the formation of detectable 11-oxo-ETE-CoA. (C) Reduction of double bonds for 15-oxo-ETE-CoA.

To confirm this initial observation and test if the newly formed oxo-CoAs undergo reduction of double bonds, LoVo cells were treated with 25 μM AA, 10 μM 11-oxo-ETE, 10 μM 11-oxo-ETE-ME, or 10 μM 15-oxo-ETE. Following an extraction with specific recovery of acyl-CoAs (22), LC-SRM/MS was used to monitor the formation of oxo-ETE-CoAs and their saturated products. By taking advantage of the predictable neural loss of 507 Da, SRM transitions were designed for the parent ion corresponding to the oxo-ETE-thioester (m/z 1068) or the saturated products resulting from the one to four double bond reductions (m/z 1070, 1072,1074, 1076). The product ions monitored in the SRM transition corresponded to the neutral loss 507 (Fig.2).

Fig. 3A shows the chromatographic profile that resulted after LoVo cells treatment with AA. Consistent with the m/z 1068 observed in the LC-MS/MS scanning (Fig. 1B), Fig. 3A shows a clear chromatographic peak corresponding to the oxo-ETE-CoA. Peaks corresponding to oxo-ETE-CoAs with one saturation (m/z 1070) and two unsaturations (m/z 1072) were also observed at varying intensities (Fig. 3A). Treatment with the methyl ester of 11-oxo-ETE, 11-oxo-ETE-ME produced a similar distribution of oxo-ETE-CoAs (Fig. 3B). Interestingly treatment with both 11-oxo-ETE (Fig 3C) and 15-oxo-ETE (Fig 3D) resulted in similar levels of oxo-ETE-CoAs (m/z 1068).

Fig 3. LC-MS/MS chromatograms for oxo-ETE-acyl-CoA species and reduced metabolites.

Extracted ion chromatograms of acyl-CoA LC-MS/SRM analysis from LoVo Cells treated with (A) 25 μM AA (B) 10 μM 11-oxo-ETE-ME (C) 10 μM 11-oxo-ETE (D) 10 μM 15-oxo-ETE. The m/z transitions corresponding to the reduction of 0–4 double bonds were monitored (1068→561, 1070→563, 1072→565, 1074→567, 1076→569).

To further investigate the nature of the saturation, two human colon adenocarcinoma lines, LoVo and HCA-7, were treated with 11-oxo-ETE. The formation of 11-oxo-ETE-CoAs and the saturated 11-oxo-ETE-CoA thioesters was monitored over 4 h. To account for the losses that could occur during the cell extraction and sample preparation procedure, isotopically labeled arachidonoyl-CoA was spiked before into the sample before extraction. [13C3 15N1]-Arachidonoyl-CoA was generated as previously described (19) and used as an internal standard for normalization. In the initial 30 min, 11-oxo-ETE-CoA was formed at higher concentrations in the LoVo cells (Fig. 4A) vs HCA-7 cells (Fig. 4C). After 4 h both cell lines showed negligible amounts of the 11-oxo-ETE-CoA (Fig. 4A and 4C). The patterns of formation for the observed saturated oxo-ETE-CoAs were also different between the two cell lines, where detectable amounts of all four saturated oxo-ETE-COAs were seen in the LoVo cells (Fig. 4B), but only 2 saturations were detected in the HCA-7 cells (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, 11-oxo-ETE-CoA with 3 unsaturations (m/z 1074) was almost as abundant as the product with 2 unsaturations (m/z 1072) in the LoVo cells (Fig. 4B) but not detectable in the HCA-7 cells (Fig. 4D), indicating that the lack of 3 unsaturation product (m/z 1074) was not due to the amount formed being under the limit of detection, but rather due to a different expression of the reducing enzymes in different cell lines. This also strongly suggests that it is not a single enzyme responsible for all of the double bond reductions across the acyl-chain.

Fig 4. Time course of 11-oxo-ETE-CoA thioesters.

Quantification over 4 h of different oxo-ETE-CoAs from (A) 11-oxo-ETE-CoA in LoVo cells (B) saturated products from 11-oxo-ETE-CoAs in LoVo cells (C) 11-oxo-ETE-CoA in HCA-7 cells (D) saturated products from 11-oxo-ETE-CoAs in HCA-7 cells. SID-LC-MS/SRM were performed using [13C3 15N1]-arachidonoyl-CoA as an internal standard for quantitation. Values are expressed in area under the peak for (Analyte/ISTD) to capture the full range of values over the timecourse.

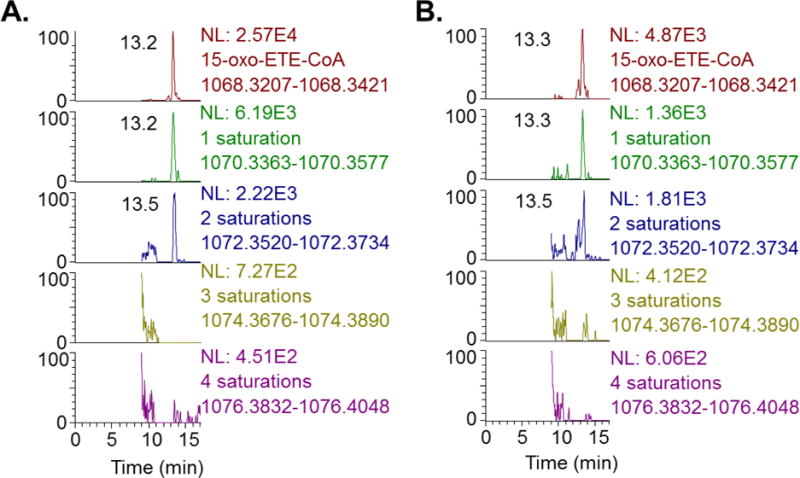

To further confirm the relevance and rigor of our findings in cell culture, we utilized an ex vivo model with human platelets. Human platelets from expired platelet concentrate formed detectable amounts of oxo-ETE-CoA after treatment with, 50 μM arachidonic acid (Fig. 5A), 10 μM 15-oxo-ETE (Fig. 5B) for 1 hour. The mono- and di- saturated oxo-ETE-CoAs were also detected. Accurate mass assignment confirmed the identification of the oxo-ETE-CoA metabolites (m/z predicted, m/z observed, delta-ppm; oxo-ETE-CoA; 1068.3314, 1068.3412, +9.1; monosaturated oxo-ETE-CoA; 1070.3471, 1070.3505,+3.1; di-saturated oxo-ETE-CoA; 1072.3627, 1072.3670, +4.0). No detectable levels were found in quiescent vehicle treated platelets (data not shown).

Fig 5. LC-HRMS chromatograms for oxo-ETE-acyl-CoA species and reduced metabolites from platelets.

Extracted ion chromatograms of acyl-CoA LC-HRMS analysis from human platelets treated with (A) 50 μM AA (B) 10 μM 15-oxo-ETE. Mass windows are set at +/− 5ppm from the predicted exact mass for the oxo-ETE-CoA with 0–4 reduced double bonds (saturations) as indicated.

Discussion

The study of metabolism of eicosanoids has mostly focused on the generation of bioactive lipids. The transformation of the initial products remains less explored. Existing literature on eicosanoid metabolism for COX/15-PGDH products has focused on PGE2, the prostaglandin transporter (PGT), and the 15-PGDH (also called PG15DH) dependent product 15-keto-PGE2 (26). A second level of transformation via a double bond reduction forms the product 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE2. However, the COX/PGDH pathway also produces 11-oxo- and 15-oxo-ETE. 15-oxo-ETE can also be generated by 15-LOX/PGDH metabolism. Existing work on the metabolism of 15-oxo-ETE has described the generation and signaling of complex lipids integrating 15-oxo-ETE (17). This work expands the knowledge of these pathways to include additional downstream products that may be critical intermediates in the involvement of eicosanoids in non-GPCR signaling functions.

Notably, saturation of mono- or poly-unsaturated fatty acids has been described through mitochondrial and peroxisomal metabolism (27). This is in opposition to the microsomal desaturation and chain elongation involved in PUFA anabolism (28). However, description of eicosanoid acyl-CoA thioesters is relatively sparse in the literature, as is work on the expression and specificity of acyltransferases in general (29). Although we extended our discovery method to specifically look for CoA thioesters of PGE2 and the proximal metabolites 15-keto-PGE2 and 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE2, (m/z 1104, m/z 1118 and m/z 1120) we could not detect any of these products (Fig1B). Transitions corresponding to the loss of 507 amu from the above m/z were also monitored (data not shown) but no peaks were detected corresponding to prostaglandins-CoA. We also failed to detect the CoA thioester of the 11-oxo-ETE-methyl ester (data not shown). This further supports the hypothesis that the identified product is in fact a thioester formed via linkage through the carboxylic acid group when we treated cells with 11-oxo-ETE-methyl ester. Fig. 3B shows the same pattern of formation as the treatment with 11-oxo-ETE (Fig. 3C), indicating that the methyl group is cleaved before the reaction with the acyl-transferase. This de-esterification is in line with results for treatment of HUVECs, LoVos and HCA-7s with 11-oxo-ETE-ME and 15-oxo-ETE-ME as previously published (30). Monitoring the transition corresponding to the 11-oxo-ETE-methyl ester-CoA (increase of 14 amu due to the methyl group) showed no product (data not shown). This distinction is important since the α,β-unsaturated ketone moiety could potentially result in a 1,4-Michael addition product (4). This distinction also suggests that the carnitine intermediate (requiring a free carboxylic acid) is necessary for subcellular transport. A related limitation of this study is that we did not examine the identity or enzymology of the reductases responsible for the patterns of double bond saturation we observed. Nor were we able to determine the position and order of double bond saturation. Further study is warranted on this topic because the saturation of the double bond proximal to the carbonyl would remove the α,β-unsaturated ketone moiety.

Importantly, formation of eicosanoid thioesters provides an intermediate for further metabolism. The acyl-CoA thioester can act as a substrate for acyl-transferases in lipid metabolism, transferring the acyl-group to a polar head group. This general pathway may be important in the regulation of regeneration of poly-unsaturated fatty acids versus their catabolism. Reduction of double bonds in the CoA intermediate can directly generate reducing equivalents such as NADH or NADPH. It may also further explain the generation of polar lipids with acyl-chains composed of eicosanoids. Further metabolism of the eicosanoids via β-oxidation, or lysosomal α-oxidation, may also generate reducing equivalents and acetyl-CoA. This pathway may explain the findings that etomixmir, a carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 inhibitor, prevented platelet function in a cPLA2 dependent manner (18).

Highlights.

Acyl-coenzyme A thioesters of 11- and 15-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid were identified

Subsequent saturations of double bonds within the metabolites were detected

15-oxo-ETE-CoA was formed in human platelets

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH grants U54HL117798, P42ES023720, P30ES013508, and P30CA016520 to IAB and K22ES26235, R03CA211820, R21HD087866 to NWS.

List of non-standard Abbreviations

- (COX)

Cyclooxygenase

- (AA)

arachidonic acid

- (HETE)

hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids

- (HPETE)

hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- (15-PGDH)

15-prostaglandin dehydrogenase

- (oxo-ETE)

oxoeicosatetraenoic acid

- (PGE2)

prostaglandin E2

- (EP)

prostaglandin E receptor

- (FBS)

fetal bovine serum

- (15d-PGJ2)

15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2

- (LOX)

lipoxygenase

- (ME)

methyl ester

- (SPE)

solid phase extraction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294(5548):1871–5. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X, Zhang S, Arora JS, Snyder NW, Shah SJ, Blair IA. 11-Oxoeicosatetraenoic acid is a cyclooxygenase-2/15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase-derived antiproliferative eicosanoid. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24(12):2227–36. doi: 10.1021/tx200336f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey JM, Bryant RW, Whiting J, Salata K. Characterization of 11-HETE and 15-HETE, together with prostacyclin, as major products of the cyclooxygenase pathway in cultured rat aorta smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 1983;24(11):1419–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SH, Rangiah K, Williams MV, Wehr AY, DuBois RN, Blair IA. Cyclooxygenase-2-mediated metabolism of arachidonic acid to 15-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid by rat intestinal epithelial cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20(11):1665–75. doi: 10.1021/tx700130p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei C, Zhu P, Shah SJ, Blair IA. 15-oxo-Eicosatetraenoic acid, a metabolite of macrophage 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase that inhibits endothelial cell proliferation. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76(3):516–25. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.057489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai JW, Wang Z, Gui SB, Zhang YZ. Loss of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase indicates a tumor suppressor role in pituitary adenomas. Oncol Rep. 2012;28(2):714–20. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Z, Wang X, Lu Y, Du R, Luo G, Wang J, Zhai H, Zhang F, Wen Q, Wu K, Fan D. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is a tumor suppressor of human gastric cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10(8):780–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.8.12896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai HH, Tong M, Ding Y. 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) and lung cancer. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;83(3):203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Donnell VB, Murphy RC. New families of bioactive oxidized phospholipids generated by immune cells: identification and signaling actions. Blood. 2012;120(10):1985–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-402826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth EM, Grosser T, Wang M, Yu Y, FitzGerald GA. Prostanoids in health and disease. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S423–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800094-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell-Parikh LC, Ide T, Lawson JA, McNamara P, Reilly M, FitzGerald GA. Biosynthesis of 15-deoxy-delta12,14-PGJ2 and the ligation of PPARgamma. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(6):945–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI18012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, O’Donnell VB, Freeman BA. Convergence of nitric oxide and lipid signaling: anti-inflammatory nitro-fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(8):989–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher JU, Pillinger MH. 15d-PGJ2: the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin? Clin Immunol. 2005;114(2):100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groeger AL, Cipollina C, Cole MP, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Rudolph TK, Rudolph V, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 generates anti-inflammatory mediators from omega-3 fatty acids. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(6):433–41. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder NW, Golin-Bisello F, Gao Y, Blair IA, Freeman BA, Wendell SG. 15-Oxoeicosatetraenoic acid is a 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase-derived electrophilic mediator of inflammatory signaling pathways. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;234:144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozak KR, Crews BC, Morrow JD, Wang LH, Ma YH, Weinander R, Jakobsson PJ, Marnett LJ. Metabolism of the endocannabinoids, 2-arachidonylglycerol and anandamide, into prostaglandin, thromboxane, and prostacyclin glycerol esters and ethanolamides. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(47):44877–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond VJ, Morgan AH, Lauder S, Thomas CP, Brown S, Freeman BA, Lloyd CM, Davies J, Bush A, Levonen AL, Kansanen E, Villacorta L, Chen YE, Porter N, Garcia-Diaz YM, Schopfer FJ, O’Donnell VB. Novel keto-phospholipids are generated by monocytes and macrophages, detected in cystic fibrosis, and activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(50):41651–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.405407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slatter DA, Aldrovandi M, O’Connor A, Allen SM, Brasher CJ, Murphy RC, Mecklemann S, Ravi S, Darley-Usmar V, O’Donnell VB. Mapping the Human Platelet Lipidome Reveals Cytosolic Phospholipase A2 as a Regulator of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics during Activation. Cell Metab. 2016;23(5):930–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder NW, Basu SS, Zhou Z, Worth AJ, Blair IA. Stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of cellular and tissue medium- and long-chain acyl-coenzyme A thioesters. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2014;28(16):1840–8. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worth AJ, Marchione DM, Parry RC, Wang Q, Gillespie KP, Saillant NN, Sims C, Mesaros C, Snyder NW, Blair IA. LC-MS Analysis of Human Platelets as a Platform for Studying Mitochondrial Metabolism. J Vis Exp. 2016;(110):e53941. doi: 10.3791/53941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frey AJ, Feldman DR, Trefely S, Worth AJ, Basu SS, Snyder NW. LC-quadrupole/Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry enables stable isotope-resolved simultaneous quantification and (1)(3)C-isotopic labeling of acyl-coenzyme A thioesters. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(13):3651–8. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9448-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minkler PE, Kerner J, Ingalls ST, Hoppel CL. Novel isolation procedure for short-, medium-, and long-chain acyl-coenzyme A esters from tissue. Anal Biochem. 2008;376(2):275–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu SS, Mesaros C, Gelhaus SL, Blair IA. Stable isotope labeling by essential nutrients in cell culture for preparation of labeled coenzyme A and its thioesters. Anal Chem. 2011;83(4):1363–9. doi: 10.1021/ac1027353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basu SS, Blair IA. SILEC: a protocol for generating and using isotopically labeled coenzyme A mass spectrometry standards. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudolph V, Schopfer FJ, Khoo NK, Rudolph TK, Cole MP, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Groeger AL, Golin-Bisello F, Chen CS, Baker PR, Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acid metabolome: saturation, desaturation, beta-oxidation, and protein adduction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(3):1461–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802298200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nomura T, Lu R, Pucci ML, Schuster VL. The two-step model of prostaglandin signal termination: in vitro reconstitution with the prostaglandin transporter and prostaglandin 15 dehydrogenase. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65(4):973–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunau WH, Dommes V, Schulz H. beta-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria, peroxisomes, and bacteria: a century of continued progress. Prog Lipid Res. 1995;34(4):267–342. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprecher H. Metabolism of highly unsaturated n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1486(2–3):219–31. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lands WE. Stories about acyl chains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1483(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder NW, Revello SD, Liu X, Zhang S, Blair IA. Cellular uptake and antiproliferative effects of 11-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(11):3070–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M040741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]