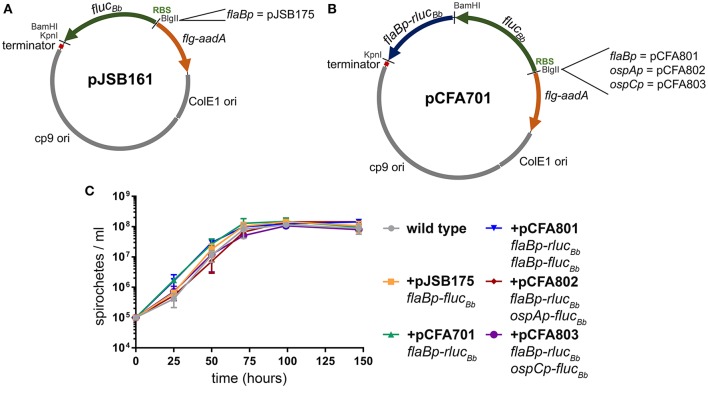

Figure 1.

B. burgdorferi luciferase plasmids. All of the B. burgdorferi luciferase shuttle vectors were derived from pJSB161, which contains a Rho-independent transcription terminator sequence (terminator); ORFs 1, 2, and 3 of the B. burgdorferi cp9 replication machinery (cp9 ori); E. coli origin of replication (ColE1 ori); and the spectinomycin/streptomycin resistance cassette (flg-aadA) (Blevins et al., 2007). (A) The B. burgdorferi shuttle vector pJSB161 features a promoterless, B. burgdorferi codon optimized Photinus pyralis luciferase (flucBb), an upstream ribosome binding site (RBS) and a unique BlgII restriction site (Blevins et al., 2007). The plasmid pJSB175 was generated by addition of the flaBp promoter upstream of flucBb in pJSB161 (Blevins et al., 2007). (B) The B. burgdorferi codon optimized Renilla reniformis luciferase (rlucBb) gene under the control of the flaB promoter (flaBp-rlucBb) was added to pJSB161, generating the B. burgdorferi dual luciferase shuttle vector, pCFA701. Plasmids, pCFA801, pCFA802, and pCFA803, harbor the flaB, ospA, and ospC promoters, respectively, upstream of flucBb. (C) The density of B. burgdorferi clone A3-68Δbbe02 (wild type) alone or harboring various B. burgdorferi luciferase plasmids was assessed over a period of 144 h using a Petroff Hauser counting chamber and dark-field microscopy. The data are presented as the mean spirochete density (spirochetes/ml) ± standard deviation over time (hours).