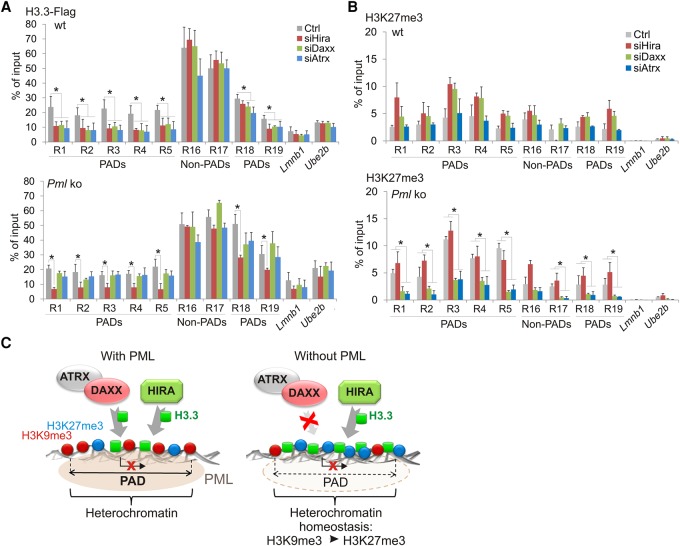

Figure 5.

Absence of PML promotes H3.3 loading by HIRA in PADs. (A) ChIP-qPCR of H3.3-Flag in PAD and non-PAD sites in wt and Pml ko MEFs after Hira, Daxx, or Atrx knock-down. (B) ChIP-qPCR of H3K27me3 under the same conditions as in A. All ChIPs: mean ± SD of three to five experiments. (*) P < 0.02; Fisher's exact tests. Position of amplicons is given in Supplemental Table 4. (C) PML organizes heterochromatin domains and modulates H3.3 loading. (Left) In wt cells, PML associates with heterochromatic H3K9me3-rich domains (PADs). Deposition of H3.3 in PADs is low relative to inter-PAD regions, and can be mediated by HIRA, DAXX, or ATRX. (Right) In the absence of PML, H3K9me3 levels are reduced in PADs. The ATRX/DAXX complex loses is ability to load H3.3 in these regions. In contrast, HIRA retains its ability to deposit H3.3 in PADs, supporting the idea of a gap-filling mechanism (Ray-Gallet et al. 2011) established to preserve chromatin integrity. A heterochromatic state is maintained in PADs by an increase in H3K27me3 in a manner implicating the ATRX/DAXX complex, perhaps through the ability of ATRX to recruit the PRC2 complex to chromatin (Sarma et al. 2014). Our results suggest an interplay between the HIRA-H3.3 and ATRX/DAXX-Polycomb pathways to maintain heterochromatin homeostasis in domains where H3K9me3 is compromised in the absence of PML, with the purpose of keeping these regions transcriptionally silent.