As the FDA's drug approval process comes under increasing scrutiny in the US, Health Canada moves closer to beginning concurrent drug reviews with the American regulator.

“We're looking at the potential to implement pilot activities that would allow for concurrent reviews of materials submitted to both Health Canada and to the United States,” says Dr. Robert Peterson, director-general of Health Canada's therapeutic products directorate. “We would hope that that would take place within the next year.”

The joint reviews would take place under the terms of a memorandum of understanding that Canada and the United States signed in April 2004 (CMAJ 2004;171:121). The agreement is intended to reduce bureaucratic hurdles for manufacturers applying to have new drugs approved in both jurisdictions, and to bring new drugs to market faster.

In the past few months, the FDA has been criticized for the quality of its drug approvals and postmarketing system after problems involving COX-2 inhibitors. The criticisms intensifed when a senior drug reviewer accused the agency of ignoring his warnings about rofecoxib (Vioxx) and 5 other new drug submissions, prompting one US Senator to call for a congressional inquiry.

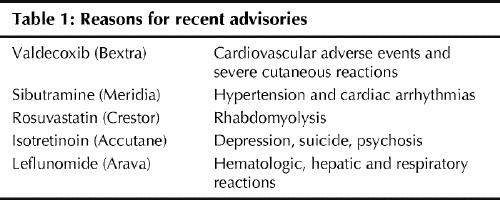

David Graham, associate director for science and medicine in the FDA's Office for Drug Safety, told the US Senate Finance Committee in November that the FDA suppressed his concerns about rofecoxib, as well as other medications. He listed 5 drugs he said should be withdrawn from the market or examined more closely. All of the medications (Accutane, Arava, Bextra, Crestor and Meridia) are also approved in Canada and advisories have been issued (Table 1.

Table 1

“Rofecoxib is a terrible tragedy and a profound regulatory failure,” Graham testified at the hearing. “I would argue that the FDA, as currently configured, is incapable of protecting America against another rofecoxib. We are virtually defenceless.”

Graham cited what he termed the “inherent conflict of interest” in having the same office within the FDA that approves a new drug — the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research — responsible for taking postmarket regulatory action against it. “When a serious safety issue arises postmarketing, their immediate reaction is almost always one of denial, rejection and heat. They approved the drug so there can't possibly be anything wrong with it,” Graham said.

Canadian experts say Graham's criticisms raise similar questions about Canadian drug regulation, and caution Canadian regulators about getting closer to the FDA.

“I don't believe that the issues that the FDA faces are independent to that of Health Canada. You have these same concerns,” says Dr. Muhammed Mamdani, senior scientist with Toronto's Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

In Washington, Dr. Sandra Kweder, deputy director of the Office of New Drugs Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, denied that the agency pressured Graham to withdraw or change findings in a paper he presented about rofecoxib. She also disputed his concerns about the 5 drugs that he says require further study or withdrawal.

Health Canada's Peterson refused to comment about Graham's testimony or its impact on the Canadian agency's review of the 5 drugs in question. The department is conducting an ongoing re-evaluation of the drugs' “benefit-to-risk” profiles, he said.

But a US watchdog organization, Public Citizen, says it has longstanding concerns about the FDA's drug approval process and the conflict of interest implied by industry funding of the approval process.

“The twin engines of the FDA's demise are that the funding of most of the drug review is coming directly from the pharmaceutical industry, and there is no congressional oversight,” says Dr. Sidney Wolfe of Public Citizen.

“There are serious problems in both the review function … and also in the postmarket surveillance process.”

Subsequent to Graham's testimony, a survey of almost 400 FDA scientists that became public through a US Freedom of Information request indicates that almost one-fifth of the scientists have been pressured to approve a new drug despite their reservations about its safety. Most of the scientists surveyed also said they doubted the FDA's ability to monitor prescription drugs once they were on the market.

The findings came from a report by the Health and Human Services Department's inspector general. When the report was originally released publicly in March 2003, the survey was not included in the document.

Wolfe, who is familiar with Health Canada's drug review process, says the system here also promulgates a conflict of interest because of its cost-recovery policy. The Treasury Board policy requires departments to charge private-sector clients, where appropriate, for services rendered. As a result, the pharmaceutical industry also pays for the drug reviews Health Canada conducts.

That process breeds familiarity between the companies and the bureaucrats, says Mary Wiktorowicz, an associate professor at York University's School of Health Policy and Management. Wiktorowicz, who compared 4 drug regulatory approval processes (in Canada, the US, Britain and France), says treating the pharmaceutical industry as the regulatory agent's client can be detrimental to the public interest. When companies become the regulator's customers, the regulators “want to be able to help them, because they realize the enormous research and the resources that have gone into the clinical trials. So they want to be able to deliver a positive message for them.”

Although the FDA's drug approval process is, on paper, more stringent than Canada's, the US expert advisory committees that review drug companies' data have been dogged with individual conflicts of interest, Wiktorowicz says. There is a small pool of experts on particular drugs, and it's difficult to find any who have not been involved in the clinical trials under review, or who have not been paid by the same pharmaceutical company for other trials.

“There's a small world, if you look in any particular field — the experts are well-known,” she says. That poses a problem for increased harmonization between the Canadian and US drug review systems, she adds. “There needs to be a way to get around that.”

The problem for Canada, says Toronto's Mamdani, is that Health Canada clearly does not have the money or the staff required to perform independent drug reviews.

“Where are you going to come up with all the money to do this work?” he asks.

Although Mamdani supports international collaboration among drug regulators, he believes Canada should be relying on the databases it already has, such as drug utilization information from the Ontario Drug Benefits Program, to make better use of postmarketing surveillance for adverse drug events (CMAJ 2003;169 [11]:1167-70).

Linking that database with the abstract database on hospital admissions can provide an excellent database for tracking drug interactions among seniors in Ontario, he says. In BC, regulators have access to an electronic system — Pharmanet — that captures every prescription filled by all the pharmacies in a central database, which can also be linked to outcomes.

“Adverse drug reporting is really weak” as a method of postmarket surveillance, Mamdani says. “And that's the main system Health Canada relies on. We have much better and more powerful resources — why aren't we relying on them?”

At the University of Victoria, Dr. Eike-Henner Kluge, a medical ethicist, also questions what he calls “extreme reliance” on US data.

Kluge recommends that new drugs be issued conditional licences only, until Phase IV postmarketing surveillance studies can be carried out to examine adverse events in actual populations. Once a drug is deemed safe based on that data, it could be issued with a permanent licence, he suggests.

“Given the electronic databases these days and the data sharing and various provincial networks, this would cost very little to implement,” says Kluge. “This would enhance physicians' ability to provide important patient care, and it would also put their minds at ease. It would be in line with the mandate of Health Canada to make products as safe as possible.”

Health Minister Ujjal Dosanjh has also suggested physicians and other health care providers should be required to report adverse drug events to Health Canada, instead of the current voluntary reporting system. But that would require working with the regulatory bodies in each province to reach an agreement. — Laura Eggertson, CMAJ

Figure. Vioxx was “a profound regulatory failure,” says an official at the FDA Office for Drug Safety. Photo by: Canapress