Abstract

Objective

The risk of leg amputation among patients with diabetes has declined over the past decade, while use of preventative measures--such as hemoglobin A1c monitoring--have increased. However, the relationship between hemoglobin A1c testing and amputation risk remains unclear.

Methods

We examined annual rates of hemoglobin A1c testing and major leg amputation among Medicare patients with diabetes from 2003 to 2012 across 306 hospital referral regions (HRRs). We created linear regression models to study associations between hemoglobin A1c testing and lower extremity amputation.

Results

From 2003 to 2012, proportion of patients who received hemoglobin A1c testing increased 10% (74% to 84%), while their rate of lower extremity amputation decreased 50% (430 to 232/100,000 beneficiaries). Regional hemoglobin A1c testing weakly correlated with crude amputation rate in both years (2003 R=−0.20, 2012 R=−0.21), and further weakened with adjustment for age, sex, and disability status (2003 R=−0.11, 2012 R=−0.17). In a multivariable model of 2012 amputation rates, hemoglobin A1c testing was not a significant predictor.

Conclusion

Lower extremity amputation among patients with diabetes nearly halved over the past decade, but only weakly correlated with hemoglobin A1c testing throughout the study period. Better metrics are needed to understand the relationship between preventative care and amputation.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly all professional societies recommend regular hemoglobin A1c testing for patients with diabetes.1 These recommendations are based on evidence suggesting that good glycemic control—as measured by hemoglobin A1c levels—can lead to fewer microvascular complications, including amputations.2–4 The National Quality Forum endorses hemoglobin A1c testing rate as a measure of physician quality. It is currently used as a performance standard in Accountable Care organizations and has been cited as a proposed measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services in 2014. 5–7

Hemoglobin A1c is an excellent marker of disease control in diabetes. However, a direct link between the level of quality of diabetic care—as measured by hemoglobin A1c—and amputation risk has yet to be documented in large cohorts. Meta-analysis of quality-of-care indicators failed to show a significant improvement in patient outcomes.8 However, smaller studies have shown improved outcomes in patients with diabetes, whose physicians utilize quality measures. 9,10 Furthermore, earlier regional analyses by our group has shown improved vascular outcomes with quality diabetic care. 11

In this large analysis, we sought to examine the relationship between the use of hemoglobin A1c testing and amputation risk using a large, national dataset that would be adequately powered to examine this question in real-world practice. We examined this relationship over time, hypothesizing that higher hemoglobin A1c testing rates in recent years would be correlated with lower amputation rates, within the hospital referral regions as defined in the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare.

METHODS

Cohort Definition

Using Medicare Physician and Supplier file as well as the Medicare Denominator file, we identified all patients with diagnostic codes indicative of Diabetes between 2003 and 2012. We included patients over age 65 who had been diagnosed with diabetes in the preceding year. Patients remained in our cohort as long as they had a diagnosis code for diabetes in two of three consecutive years. We excluded patients not enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare or who were not enrolled in parts A and B for the entire year. Additional information, including age, sex, and race, were obtained from the Medicare Denominator file.

We then calculated regional rates of diabetes in 2003 and 2012 using patient zip code to create 306 hospital referral regions (HRR), as described by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.12 The denominator was the mid-year population of beneficiaries within the region. Patients aged less than 65, or with missing or incomplete data were excluded from the analysis.

In this analysis we present our findings from the years at the beginning (2003) and end (2012) of our analytic period. Analyses including all years were also performed, and yielded linear changes in these variables, and therefore for clarity we present only the first and last years in the analyses described in this report.

Hemoglobin A1C Testing

Within each HRR, we examined the proportion of diabetic patients who received one or more hemoglobin A1c test(s) within the year of interest. CPT codes were used to identify hemoglobin A1c testing, as described by Yasaitis, et al.13

Defining regional rates of amputation

Next, within each hospital referral region, we examined the proportion of patients with diabetes who underwent major lower extremity amputations. Amputation was defined as at least one inpatient hospital claim indicating the procedure within each study year: 2003 or 2012 (see Appendix 1). We studied only the first amputation per patient per year. We recorded the most proximal amputation. In the claims data, we could not distinguish between right and left side procedures. For example, if a patient underwent both a toe amputation and an above-knee amputation in a particular year, only the above-knee amputation was recorded. Toe and forefoot amputations were excluded from the primary analysis, as they carry less of a disability burden. However, when we re-ran our analysis including all amputations, the results were similar (Appendix figure). Traumatic amputations were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

We used simple linear regression models to correlate the crude relationship between regional rates of hemoglobin A1c testing and the primary outcome--lower extremity amputation--among patients with diabetes. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the strength of the correlation with an associated p-value for the linear regression.

Based on the range of rates of diabetics receiving hemoglobin A1C testing in the past year, we assigned each HRR to a quintile of hemoglobin A1C testing: in 2003, the lowest quintile contained HRRs where 41 to 70% of diabetics had received hemoglobin A1C testing, and the highest quintile contained HRRs where 79 to 87% of diabetics had received hemoglobin A1C testing in the past year. We then calculated the average amputation rate within each quintile. We then examined the relationship between regional rates of hemoglobin A1c testing and amputation rates, adjusting the amputation rates for regional differences in age, gender, and disability status.

Risk Adjustment

In an attempt to adjust for confounding by regional-level variables, we created multiple linear regression models to predict 2012 amputation rates, adjusting for regional baseline demographics and rates of health co-morbidities along with regional testing rates. All analyses were performed using SAS (College Station, TX). The Geisel School of Medicine Center for the Protection of Human Subjects granted IRB exemption for this study. Patient consent was not obtained as all conditions for waiver of consent as outlined by the policy of protection of human research subjects were met.

RESULTS

Regional variation in hemoglobin A1c testing rates in 2003 and in 2012

Overall, 73.9% of patients with diabetes received hemoglobin A1c testing in 2003. This number increased to 83.8% in 2012. As regions increased their hemoglobin A1c testing, the degree of variation among regions decreased. In 2003, the highest testing region performed testing over twice as often as the lowest-testing region: 87.5% (Whitefield, WI) to 41.5% (Oxford, MS). In 2012, this variation had decreased to 30%: 93% (Dubuque, IA) to 68.4% (Albuquerque, NM).

Regional variation in lower extremity amputation rates in 2003 and in 2012

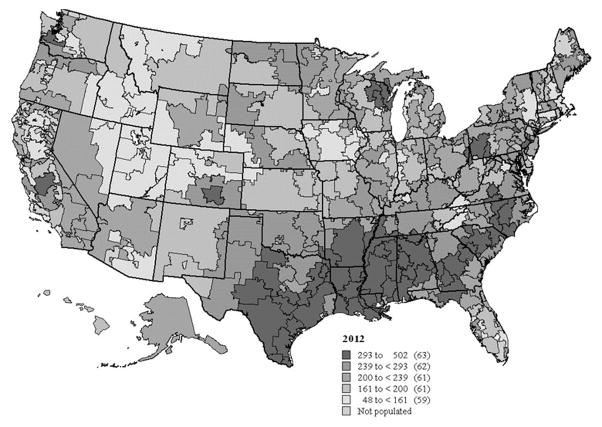

The national rate of lower extremity amputation fell from 431 per 100,000 beneficiaries in 2003 to 232 per 100,000 in 2012. Despite this trend, there was almost a 10-fold variation across hospital referral regions (Figure 1). Crude amputation rates in 2003 varied from near 0 (Grand Junction, CO) to 1210 per 100,000 beneficiaries (Corpus Christi, TX) in 2003. This variation persisted in 2012, when amputation rates ranged from 48 per 100,000 (Great Falls, MT) to 501 per 100,000 (Corpus Christi, TX).

Figure 1.

Regional variation in amputation rate in patients with diabetes, over age 65: 2012

Characteristics of patients with diabetes, by testing quintile

We examined the characteristics of patients with diabetes living in quintiles of regions with lowest to highest rates of hemoglobin A1C testing in 2012 (Table 1). Each quintile contained approximately 2.3 million beneficiaries with diabetes. Quintiles were similar in terms of age and gender, smoking, and overall comorbidities. However, quintiles of regions with lower rates of hemoglobin A1C testing have a higher percentage of racial and ethnic minorities. For example, the lowest quintile has 50% more African Americans (12.3 vs 7.4%) and over 6-fold more Hispanic patients than the highest quintile (6.1 vs 0.5%). Given the very large size of the cohort, all differences between the quintiles reach statistical significance. Although patients in the highest quintile have an increased percentage of patients with renal disease and peripheral vascular disease, these differences were not clinically significant, as most represent absolute differences of less than 1–2%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with diabetes living in quintiles of regions with lowest to highest rates of hemoglobin A1C testing in 2012. (Total n=11,943,000)

| Lowest (68–81%) (n=2,332,262) | Low (81–83%) (n=2,401,512) | Average (83–84%) (n=2,383,574) | High (85–86%) (n=2,358,147) | Highest (>86%) (n=2,467,505) | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 75.5 (7.0) | 75.8 (7.0) | 75.7 (7.0) | 75.9 (7.0) | 76.0 (7.1) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% female) | 55.8 | 56.3 | 55.2 | 54.6 | 54.9 | <0.0001 |

| Race | ||||||

| African American, % | 12.3 | 15.4 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 7.4 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic, % | 6.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid, % | 29.3 | 19.1 | 18.2 | 16.7 | 16.5 | <0.0001 |

| Charlson Score | ||||||

| 2003, mean (SD) | 1.4 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.3 (1.9) | <0.0001 |

| 2012, mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.7 (2.2) | 1.6 (2.2) | 1.6 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Renal disease, % | 12.4 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 11.4 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, % | 12.9 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 11.4 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| Obese, BMI >30, % | 27.8 | 28.8 | 28.9 | 28.5 | 28.5 | <0.0001 |

| Smoker, % | 19.0 | 19.7 | 20.2 | 20.0 | 20.0 | <0.0001 |

| Median Household income, US $ (SD) | 50,996 (20,614) | 57,250 (24,091) | 54,676 (22,669) | 52,401 (17,918) | 52,458 (17,559) | <0.0001 |

P-value by simple test of trend

Association between hemoglobin A1c testing and amputation

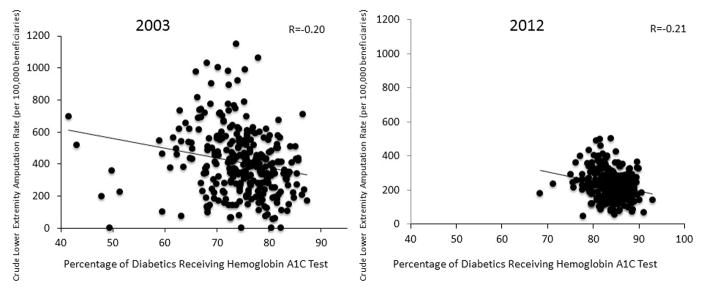

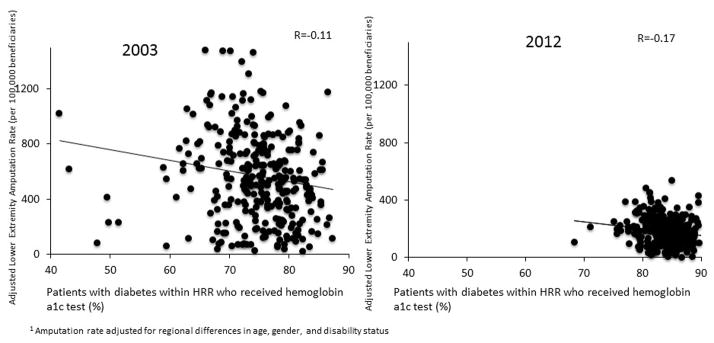

We found a weak inverse correlation between regional hemoglobin A1c tesing and lower extremity amputation in 2003 (R=−0.20) and in 2012 (R = −0.21, Figure 2). That is--regions with higher testing had lower rates of amputation among patients with diabetes. When amputation rates were adjusted for demographic regional differences (age, sex, disability status), this relationship was attenuated in both 2003(R=−0.11) and 2012(R=−0.17, Figure 3). The strongest relationship was between 2003 testing rates and 2012 amputation rates (R=−0.27), which remained relatively unchanged with adjustment for amputation rates (R=−0.22).

Figure 2.

Crude association of regional hemoglobin A1c testing rates and amputation 2003 and 2012.

Figure 3.

Association of regional hemoglobin A1c testing rates and adjusted1 amputation rates: 2003 and 2012.

Next, we examined these relationships by quintile of hemoglobin A1c testing (Figure 4). In 2003, we found that regions with the lowest hemoglobin A1c testing rates (41–70% of patients with diabetes) had 40% more lower extremity amputations than those within the highest strata of testing (460 vs 349 per 100,000). In 2012, despite increases in hemoglobin A1c testing and decreases in lower extremity amputation, the lowest strata of testing still had 27% more lower extremity amputations than the highest (261 vs 206 per 100,000).

Figure 4.

Association of regional hemoglobin A1c testing quintiles with mean amputation rates, 2003 and 2012

In multivariate linear regression adjusting for regional differences in age, sex, race, income, and comorbidities, regional rates of hemoglobin A1c testing were not predictive of 2012 amputation rate (Appendix 2). Significant predictors of amputation rate were limited to 2003 amputation rate and female gender.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, hemoglobin A1c testing rates have increased because of an emphasis on adherence to preventive guidelines that include hemoglobin A1C testing rates as a standard measure. At the same time, we found in nearly every region of the United States, amputation rates have fallen over the last decade. While many have presumed that these two events are related, our observational evidence fails to directly support this presumption. In both 2003 and 2012, there was a weak inverse correlation between regional rates of hemoglobin A1c testing and lower extremity amputation rates. However, after adjusting for regional age, gender and disability, hemoglobin A1c testing rates were not associated with amputation rates in 2012.

Our study adds a population-level perspective to already-published evidence on this topic. Multiple trials have shown a strong correlation with good glycemic control and reduction in overall macrovascular complications in individual patients. 2–4,14 Furthermore, studies examining the relationship of physician and system performance metrics on patient level outcomes have found modest correlation. A case control study comparing Medicare patients with lower extremity amputations to those without in West Virginia found an association with physician diabetic care quality measures—such as rates of annual hemoglobin A1c testing and amputation rates. 9 Earlier work has found patients with diabetes who undergo revascularization procedures in high-testing areas enjoy longer amputation-free survival than those in lower-testing areas.11

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of the topic, however, Sidorenkov et al failed to show a relationship between hemoglobin A1c testing among physicians and bad outcomes—such as lower extremity amputations.8 Furthermore, a review of system-wide quality initiatives in the Kaiser-Permanente Health care system in the mid-1990s found little association with increased frequency of all diabetic testing—including hemoglobin A1c—and lower extremity amputation, though increased levels of testing were strongly associated with more intensive medical therapy.15 Our study supports these findings with population-level analysis: annual hemoglobin A1c testing as a process measure of diabetic care quality does not strongly correlate with decreased amputation risk.

Current physician and system-level metrics of diabetic care quality—as measured by hemoglobin A1C testing—do not correlate well with decreases in amputation. We hypothesize that these annual measures do not fully capture the complexity of care for the patient with diabetes. A variety of factors – patient participation, adherence, and the longitudinal quality of care for patients with diabetes all are likely to explain differences in vascular outcomes such as amputation. Many argue, in fact, that successful prevention strategies are longitudinal in nature.16,17 Studies have found various measures of care intensity, such as primary care visit frequency or regular hemoglobin A1c testing are associated with improvements in glycemic control.10,18–20 Such measures—while more complex to obtain—would better encompass quality of care obtained by a patient with diabetes, and likely show a closer association with outcomes.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. As a retrospective analysis of administrative claims, it lack clinical detail. Most notably, we do not know the average value of the hemoglobin A1c was in any of the testing regions. Because recommended quality metrics similarly do not specify target values, the use of claims data is well-suited to this study aim. 21 Second, our analysis was performed on a regional level and could not fully adjust for differences in socioeconomic characteristics and access to care that may exist among different hospital referral regions. Third, as a cross sectional study a decade apart, we do not know the temporal relationship of hemoglobin A1c testing and amputation prevention. Future work will focus on this relationship on an individual level. Lastly, we were limited in our ability to evaluate improvements in preventative care overall. These improvements have been hypothesized to be a key driver in decreases in complications from diabetes. Our findings would support this hypothesis, given that overall amputation rates have improved.

CONCLUSION

Patients with diabetes living in regions with high hemoglobin A1c testing rates have a better chance of avoiding amputation than those that live in a region where testing is not as frequent. However, improvements in annual hemoglobin A1c testing rate do not reflect improvements in diabetic care quality within a region. In order to more effectively reduce amputation rates within at-risk regions, more focus should be placed on improving metrics to better understand relationships between the quality of care provided to patients with diabetes and cardiovascular outcomes such as amputation.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. Diagnostic and procedural codes used in the analysis.

Appendix 2. Association of regional level-factors with 2012 Amputation rates, by hospital referral region

Appendix 3. Association of regional hemoglobin A1c testing rates and all lower extremity amputations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through NIH grant 1U01AG046830-01 (Technology Diffusion, Health Outcomes, and Health Expenditures, Jonathan Skinner, PI)

Footnotes

FUNDING/DISCLOSURES: This study was presented as a mini-presentation (entitled “What matters most in limiting amputation among Diabetics: where you start, where you finish or how much you improve?”) in Lower Extremity Session, Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery annual meeting March 30–April1, 2015 (Miami, FL).

Contributor Information

Karina A. Newhall, Department of Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (Lebanon, NH). VA Outcomes Group (White River Junction, VT).

Kimon Bekelis, Section of Neurosurgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (Lebanon, NH).

Bjoern D. Suckow, Section of Vascular Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchock Medical Center (Lebanon, NH)

Daniel J. Gottlieb, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice (Lebanon, NH).

Adrienne E. Farber, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice (Lebanon, NH).

Philip P. Goodney, Section of Vascular Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (Lebanon, NH). The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice (Lebanon, NH). VA Outcomes Group (White River Junction, VT).

Jonathan S. Skinner, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice (Lebanon, NH).

References

- 1.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193–203. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) The Lancet. 1998;352:854–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comprehensive Diabetes Care (Composite Measure) [Last accessed April 10, 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Accessed 06-02, 2015];Eligible Providers 2014 Proposed EHR Incentive Program CQM. 2014 at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/ProposedClinicalQualityMeasuresfor2014.html.

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accountable Care Organization 2014 Program Analysis Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications 2014. Aug 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidorenkov G, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, de Zeeuw D, Bilo H, Denig P. Relation Between Quality-of-Care Indicators for Diabetes and Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68:263–89. doi: 10.1177/1077558710394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schade CP, Hannah KL. Quality of ambulatory care for diabetes and lower-extremity amputation. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22:410–7. doi: 10.1177/1062860607304991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li S, Liu J, Gilbertson D, McBean M, Dowd B, Collins A. An instrumental variable analysis of the impact of practice guidelines on improving quality of care and diabetes-related outcomes in the elderly medicare population. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23:222–30. doi: 10.1177/1062860608314940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooke BS, Kraiss LW, Stone DH, et al. Improving outcomes for diabetic patients undergoing revascularization for critical limb ischemia: does the quality of outpatient diabetic care matter? Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:1719–28. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodney PP, Dzebisashvil N, Goodman DC, Bronner KK. Variation in the Care of Surgical Conditions: Diabetes and Peripheral Arterial Disease. Lebanon, NH: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Pracice; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasaitis LC, Bubolz T, Skinner JS, Chandra A. Local Population Characteristics and Hemoglobin A1c Testing Rates among Diabetic Medicare Beneficiaries. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao W, Katzmarzyk PT, Horswell R, et al. HbA1c and lower-extremity amputation risk in low-income patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3591–8. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petitti DB, Contreras R, Ziel FH, Dudl J, Domurat ES, Hyatt JA. Evaluation of the effect of performance monitoring and feedback on care process, utilization, and outcome. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:192–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BEK. Long-term incidence of lower-extremity amputations in a diabetic population. Archives of Family Medicine. 1996;5:391–8. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.7.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:217–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenton JJ, Von Korff M, Lin EHB, Ciechanowski P, Young BA. Quality of preventive care for diabetes: Effects of visit frequency and competing demands. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4:32–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goddijn PPM, Bilo HJG, Feskens EJM, Groenier KH, van der Zee KI, Meyboom-de Jong B. Longitudinal study on glycaemic control and quality of life in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus referred for intensified control. Diabetic Medicine. 1999;16:23–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meduru P, Helmer D, Rajan M, Tseng CL, Pogoch L, Sambamoorthi U. Chronic illness with complexity: Implication for performance measurement of optimal glycemic control. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:408–18. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Quality Measures C. Comprehensive diabetes care: percentage of members 18 to 75 years of age with diabetes (type 1 and type 2) who had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) testing [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Diagnostic and procedural codes used in the analysis.

Appendix 2. Association of regional level-factors with 2012 Amputation rates, by hospital referral region

Appendix 3. Association of regional hemoglobin A1c testing rates and all lower extremity amputations.