Figure 6.

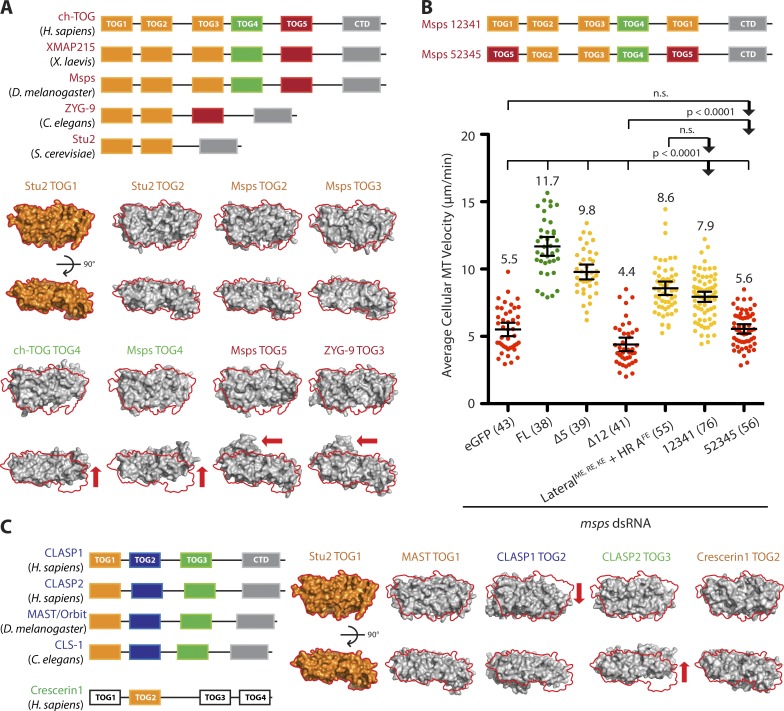

TOG domain order within an array underlies Msps-mediated MT polymerization. (A) Pairwise alignment of Stu2 TOG1 (4FFB) with other XMAP215 TOG domain structures shows that TOG architectures are unique within an array, but are positionally conserved. TOGs 1–3 are structurally similar (orange). In contrast, TOG4 has a large shift across its last three HRs (green, arrow). Interestingly, ZYG-9 TOG3 and TOG5 have HR 0 that extends away from the body of the domain (red, arrow). (B) Shuffling TOG domains differentially affects EB1 comet velocities. Msps 12341 rescued MT polymerization velocity to 7.9 µm/min. In contrast, Msps 52345 had no rescue activity. Number of cells analyzed is shown in parentheses. Mean ± 95% confidence intervals are shown; two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (C) Although XMAP215 uses a TOG array to promote MT polymerization, other TOG domain–containing MAPs use architecturally distinct arrayed TOGs to differentially regulate MT dynamics. Crescerin promotes MT polymerization in cilia, and CLASP promotes MT pause/rescue in the cytoplasm. We predict that order-specific TOG arrays underlie the ability of these three families to differentially regulate MT dynamics.