Abstract

Objective

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of 12-step peer recovery support programs with drug use disorders, especially stimulant use, and it is difficult to know how outcomes related to 12-step attendance and participation generalize to individuals with non-alcohol substance use disorders (SUDs).

Method

A clinical trial of 12-step facilitation (N=471) focusing on individuals with cocaine or methamphetamine use disorders allowed examination of four questions: Q1) To what extent do treatment-seeking stimulant users use 12-step programs and, which ones? Q2) Do factors previously found to predict 12-step participation among those with alcohol use disorders also predict participation among stimulant users? Q3) What specific baseline “12-step readiness” factors predict subsequent 12-step participation and attendance? And Q4) Does stimulant drug of choice differentially predict 12-step participation and attendance?

Results

The four outcomes variables, Attendance, Speaking, Duties at 12-step meetings, and other peer recovery support Activities, were not related to baseline demographic or substance problem history or severity. Drug of choice was associated with differential days of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) attendance among those who reported attending, and cocaine users reported more days of attending AA or NA at 1-, 3- and 6-month follow-ups than did methamphetamine users. Pre-randomization measures of Perceived Benefit of 12-step groups predicted 12-step Attendance at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Pre-randomization 12-step Attendance significantly predicted number of other Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment, 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Pre-randomization Perceived Benefit and problem severity both predicted number of Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Pre-randomization Perceived Barriers to 12-step groups were negatively associated with Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Whether or not one participated in any Duties was predicted at all time points by pre-randomization involvement in Self-Help Activities.

Conclusions

The primary finding of this study is one of continuity: prior attendance and active involvement with 12-step programs were the main signs pointing to future involvement. Limitations and Recommendations are discussed.

Keywords: 12-Step, stimulant users, peer recovery, attendance, participation, predictors

1. Introduction

1.1 Stimulant Use Disorders and 12-Step Programs

Although there is strong evidence of the effectiveness of 12-step peer recovery support programs with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) (e.g., Caldwell & Cutter, 1998; Kelly, Hoeppner, Stout & Pagano, 2012; Kelly, Stout, Magill, Tonigan, & Pagano, 2010; Moos & Moos, 2004; Tonigan, Toscova, & Miller, 1996), few studies have examined their effectiveness with drug use disorders, especially stimulant use (Carroll, et al., 2012; Schottenfeld, Moore, & Pantalon, 2011). It is difficult to know how outcomes related to 12-step attendance and participation generalize to individuals with non-alcohol substance use disorders (Witbrodt & Kaskutas, 2005).

Cocaine or methamphetamine users often comprise a substantial portion of participants in studies on those with SUDs in treatment (Timko & DeBenedetti, 2007; Timko, Billow, & DeBenedetti, 2006; Tonigan & Beatty, 2011; Witbrodt & Kaskutas, 2005). Some limited work has been done on outcomes of individuals with stimulant use disorders and 12-step programs (Carroll et al., 1998, 2000; Weiss et al., 2000a). Gossop, Stewart and Marsden (2007) reported that attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) was associated positively with abstinence at 1-year, but not 5-year follow-up for stimulant users completing treatment. Weiss et al. (2005) found that cocaine users’ active participation in 12-step groups was more important for outcomes than meeting attendance alone. Carroll et al. (1998) found that for patients dependent on both alcohol and cocaine, those receiving Twelve Step Facilitation treatment (TSF), a brief, manual-driven, structured approach introducing 12-step concepts to those in early recovery through individual and/or group sessions and linking them to 12-step peer recovery support groups, were significantly more involved in 12-step programs during the twelve-week treatment compared to those receiving Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Clinical Management, the inactive psychotherapy control. However, by the 1-year follow up alcohol and cocaine use did not differ between patients who had received TSF or CBT, suggesting that the two therapies were comparable (Carroll et al., 2000). More work is needed to better understand the mechanisms of 12-step groups for those with stimulant use disorders (Weiss et al., 2005).

Researchers have examined 12-step meeting attendance during and following treatment, attempting to identify particular sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that predicted attendance and participation (Emrick, 1987; Tonigan, et al., 1996). Most reports focused on persons with AUDs. Only one (Weiss et al., 2000b) reported on attendance for individuals with stimulant use disorder (cocaine), and a few others contained substantial numbers of stimulant users in their mixed drug use samples (Fiorentine, 1999; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000). A wide range of demographic, psychological and social variables have been examined, including age, gender, ethnicity, psychiatric and addiction severity, and social support. However, only a few variables have been found to consistently predict 12-step attendance: greater severity of substance use, (McKay, et al., 1998; Weiss et al., 2000b); more legal problems (Brown, et al., 2001; McKay et al., 1998); and prior SUD treatment (Brown et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2000b).

Instead of demographic, personality, or social variables, Kingree and colleagues (2006, 2007) explored AA-specific beliefs that might predict AA engagement. They developed and tested the Survey of Readiness for Alcoholics Anonymous Participation (SYRAAP), which assesses three dimensions: 1) perceived severity of respondent’s drug or alcohol problem; 2) perceived benefits of, and 3) perceived barriers to, participating in AA. In an evaluation of the SYRAAP with 268 treatment-seeking adults, baseline SYRAAP scores were found to reliably predict AA participation at 3- and 6-month follow-up (Kingree et al., 2007). Whether the SYRAAP also predicts engagement in 12-step groups other than AA (e.g., Narcotics Anonymous) remains to be determined. In addition, it is unclear whether the SYRAAP can predict attendance and participation of stimulant users.

1.2 Stimulant Drug of Choice and 12-step participation and attendance

Methamphetamine use is widespread and has tremendous psychiatric, behavioral and medical consequences, yet is often not separated from cocaine or other substances in reports on treatment effectiveness or utilization (Donovan & Wells, 2007). Similarly, data on methamphetamine users and their involvement in 12-step groups is scarce, despite the widespread practice of encouraging or requiring 12-step group attendance as part of recovery, and despite the emergence of Cocaine Anonymous and Crystal Meth Anonymous. One notable exception is the Matrix Model, which incorporates 12-step involvement as one component of treatment for cocaine and methamphetamine dependence (Obert, et al., 2000; Rawson, et.al., 2004). However, whether stimulant drug of choice (cocaine or methamphetamine) predicts degree of 12-step participation and attendance remains undetermined.

1.3 Study Purpose

A clinical trial of 12-step facilitation which focused on individuals with cocaine or methamphetamine use disorders (Donovan et al., 2013) allowed us to evaluate these four questions: Q1) To what extent do treatment-seeking stimulant users use 12-step programs and, which ones? Q2) Do factors previously found to predict 12-step participation among those with alcohol use disorders also predict participation among stimulant users? Q3) What specific baseline “12-step readiness” factors predict subsequent 12-step participation and attendance? And Q4) Does stimulant drug of choice predict 12-step participation and attendance?

2. Method

2.1 Main Trial Design Overview

Data for these analyses were collected as part of a multi-site randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of 12-step facilitation (Stimulant Abuser Groups to Engage in 12-Step, STAGE-12) incorporated into treatment-as-usual (TAU) against TAU alone within the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN). Methods are described in detail in Donovan et al. (2013). Participants were recruited upon admission into one of 10 participating community treatment programs (CTPs) for intensive outpatient treatment (IOP). Participating CTPs offered outpatient treatment at a level that would allow STAGE-12 individual and group sessions to replace three individual and five group sessions of TAU, resulting in an equivalent amount of treatment for both groups overall. Following baseline assessments, participants were randomized to receive either TAU with STAGE-12 or TAU alone over the course of 8-weeks. Assessments were repeated at week 4 (mid-treatment), week 8 (end-of-treatment), and 3- and 6-months post-randomization. Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the IRBs associated with each of the universities and CTPs. An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board oversaw the conduct of the trial.

2.2 Participants

Participants (N=471) were at least 18 and were recruited upon admission to a participating CTP for five to eight weeks of IOP treatment. Inclusion criteria also included use of cocaine, methamphetamine, amphetamine, or other stimulant drugs within the past 60 days, a DSM-IV diagnosis for current (within 6 months) abuse or dependence of stimulants, and consent to study procedures. If a participant had been incarcerated within the past 60 days, they were eligible if they had used one of these stimulants in the 30 days prior to incarceration. Exclusion criteria were: need of detoxification for opiate withdrawal or seeking detoxification only, enrollment in methadone maintenance treatment or residential/inpatient treatment, having a medical or psychiatric condition that would make study participation hazardous, as determined by clinic staff, incarceration for more than 60 of the 90 days before the baseline interview, or pending legal action that would preclude full participation in the study.

2.3 STAGE-12 Intervention

STAGE-12 group sessions were based on adaptation of Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) for a group format by Brown and colleagues (Brown, Seraganian, Tremblay, & Annis, 2002), and focused on helping participants better understand and incorporate core principles of 12-step programs. STAGE-12 individual sessions focused on facilitating participants’ use of 12-step recovery programs in the community. They incorporated the intensive 12-step referral model of Timko and colleagues (Timko, and Debenedetti, 2007), which sought to introduce clients to 12-step volunteers in the community who then accompanied them to their first meeting. A more detailed description of the intervention can be found in Daley, et al. (2011) and Donovan et al. (2013). CTPs encouraged 12-step involvement as part of their TAU, but this encouragement was not systematic, as in STAGE-12.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Self Help Activities Questionnaire (SHAQ)

This self-report instrument assesses the frequency of attendance at, and the degree of participation in, four types of 12-step/peer recovery support group activities (Weiss et al., 1996). Four outcome variables were obtained: (1) maximum number of days Attending AA, NA, CA, or CMA meetings in the last 30 days; (2) maximum number of days of Speaking at AA, NA, CA, or CMA meetings in the last 30 days; (3) maximum number of days of Duties (e.g. performed service such as setting up, making coffee) at AA, NA, CA, or CMA meetings in the last 30 days; and (4) number of other types of Self-Help Activities engaged in over the last 30 days (range 0 to 6). “Other Self-Help Activities” included having met with other group members or a sponsor outside of a meeting, calling or receiving a call from one’s sponsor or other group members, and reading 12-step literature for at least five minutes. SHAQ assessments were administered at baseline, mid-treatment, end-of-treatment, and 3- and 6-months follow-up. The “maximum” number of days for the first three outcomes reflects the greatest number of days within the 30-day window of assessment across the four types of meetings, with a possible range of 0 to 30. This approach to calculating days of involvement was used by Donovan and colleagues when reporting the main outcomes for this trial (Donovan et al., 2013).

2.4.2 Survey of Readiness for Alcoholics Anonymous Participation (SYRAAP)

This instrument (Kingree, et al., 2006) was administered at baseline and consists of three, 5-item subscales, each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), that measure perceived readiness for involvement in 12-step groups. The SYRAAP assesses an individual’s perceptions about the Severity of their substance use problems, the Perceived Benefits of involvement in 12-step groups, and the Perceived Barriers to participating in 12-step activities. See Table 1 for a list of items. Items were modified to include other 12-step peer recovery support groups in addition to AA.

Table 1.

Survey of Readiness for Alcoholics Anonymous Participation (SYRAAP) Items and Scales

| Perceived Benefit |

| If I go to AA/CA/NA/CMA, I will find people who can guide me in how to be clean/sober (2) |

| I will feel better about myself if I go to AA/CA/NA/CMA (4) |

| I know someone who has been helped by going to AA/CA/NA/CMA (9) |

| Going to AA/CA/NA/CMA gives me courage to change (10) |

| In AA/CA/NA/CMA, I will find people who understand me (14)

|

| Perceived Severity |

| My substance abuse problem is serious (1) |

| My friendships have suffered as a result of my use of substances (6) |

| I have been hurt financially by the use of substances (7) |

| My substance use has hurt some other people (11) |

| Using substances has interfered with my ability to deal with everyday problems (12)

|

| Perceived Barriers |

| Going to AA/CA/NA/CMA can be embarrassing to me (3) |

| Going to AA/CA/NA/CMA makes me feel depressed (5) |

| I feel like I do not belong at AA/CA/NA/CMA (8) |

| I do not want people to know that I am going to AA/CA/NA/CMA (13) |

| Going to AA/CA/NA/CMA requires changes that are too difficult (15) |

2.4.3 Substance use calendar (SUC)

This measure, similar to the Timeline Follow-back (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000; Sobell & Sobell, 1992), provides self-report of substance use and peer recovery support meeting attendance. The baseline average number of days of peer recovery support meeting attendance within a 30-day window of assessment was obtained by averaging over 3 measures of peer recovery support attendance at 60 to 90 days, 30 to 60 days, and the 30 days prior to randomization. The SUC was administered at every study visit and reconstructed data if a previous visit was missed.

2.4.4 Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992)

The ASI is a multidimensional, standardized, semi-structured interview that provides severity profiles in seven areas. ASI composite scores (Medical, Employment/support, Alcohol, Drug, Legal, Family/Social, and Psychiatric) range in value from 0 (no endorsement of problems) to 1 (maximum endorsement of problems). The ASI was collected and composite scores computed at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-up visits. The participant’s lifetime treatment for alcohol or drug use disorder, stimulant drug of choice and the interviewer’s judgment of major substance problem (cocaine, amphetamine or methamphetamine) were also obtained from the ASI.

2.4.5 Twelve Step Experiences and Expectations (TSEE)

The TSEE, developed for this project and administered at baseline, assessed individuals’ prior experience with 12-step groups. If they had experience, they were asked to indicate in which peer recovery support groups they participated, how frequently, and how helpful they perceived them to be. They also were asked about the likelihood of getting involved in a 12-step group during the treatment episode and how helpful they anticipate it would be.

2.4.6 Demographics and Diagnosis

Demographic information on age, gender, race and ethnicity were collected at baseline using a standard form. Substance use diagnosis was determined using the substance use disorder (SUD) sections of the DSM-IV Checklist (Hudziak et al., 1993).

2.5 Analysis Approach

2.5.1 Outcome Variables

The four outcome variables included the “maximum,” or greatest number, of days within the 30-day assessment window that participants 1) Attended, 2) Spoke at, or 3) had Duties at any of the four types of meetings (AA, NA, CA, or CMA), with a possible range of 0 to 30, and 4) a count of the number of other types of peer recovery support activities, termed Self-Help Activities for the purposes of these analyses (e.g., meeting or phoning members or sponsors outside a meeting, receiving phone calls from other members or one’s sponsor, reading AA, NA, CA or CMA literature for at least five minutes), engaged in over the last 30 days (range 0 to 6). Regarding maximum days Attending, Speaking or Performing Duties, if a participant attended 4 AA meetings and 1 NA meeting in the past 30 days, the maximum attendance would equal 4. Duties might include things like making coffee, setting up chairs, or clean up. We used the Attendance variable to capture simple meeting attendance, and the Speaking, Duties, and number of Self-Help Activities to represent peer recovery support participation. Because data were collected via multiple measures across multiple time points, there was some variability in the n’s.

Given over-dispersion, a negative binomial regression model was used for the maximum number of days Attending meetings, and a Poisson regression model was used for the number of other types of Self-Help Activities attended. Due to a high percentage of zeroes, a zero-inflated negative binomial model was used for both the maximum number of days of Speaking and Duties at meetings. This is a mixture model with two parts – a logistic part for assessing the zero-inflation and a negative binomial model to assess the count data which is over-dispersed at each time point. With the zero-inflated models, the logistic portion (never Speaking or never performing Duties) and the negative binomial (or count) portion are interpreted and described separately in terms of odds ratios (OR for logistic) and incidence rate ratios (RR for negative binomial) and with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) to assess statistical significance. The Poisson and negative binomial regression results without zero-inflation are interpreted only as rate ratios with 95% CIs.

Auxiliary analyses used a zero-inflated negative binomial model to evaluate the usefulness of two outcome variables (maximum days of Attendance and the number of types of Self-Help Activities) in concomitantly predicting the primary outcome of stimulant use in the STAGE-12 intervention study (Donovan et al., 2013). The primary outcome variable was the number of days of self-reported stimulant drug use within 30-day periods at baseline, mid-treatment, end-of-treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-ups. That is, analyses considered both 12-Step attendance and participation variables and the primary outcome of stimulant use at same-time assessments. The treatment effect (STAGE-12 versus TAU) was included in the models of post-baseline periods.

All models considered each of five time points for the outcomes: Baseline, mid-treatment, end-of-treatment, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up. The sample size diminishes across time due to natural and expected study attrition. However, using an alternative repeated-measures model would have been difficult to interpret. Therefore, the decision was made to provide analyses at each time point separately. The treatment effect was a significant predictor only for the number of other types of Self-Help Activities and was included in the model for time points after baseline for this outcome only.

2.5.2 Predictor Variables

Nineteen baseline variables, taken primarily from the literature on alcohol users, and the treatment effect (STAGE-12 versus TAU) were considered potential predictors of the four outcomes: 1) age, 2) race, 3) gender; 4) lifetime treatment for alcohol or 5) drug use disorder, 6) stimulant drug of choice and 7) interviewer’s judgment of major substance problem (cocaine, amphetamine or methamphetamine), 8) Psychiatric, 9) Alcohol and 10) Drug composite scores (ASI), 11) days of 12-step pre-randomization meeting attendance averaged across 60–90 days, 30–60 days, and 0–30 days pre-randomization (SUC), 12) number of other types of 12-step Self-Help activities in the 30 days prior to baseline and 13) lifetime AA/NA/CA/CMA attendance (SHAQ), 14) primary drug of choice (cocaine, amphetamine or methamphetamine; DSM-IV Checklist), 15) Perceived Benefit, 16) Perceived Severity, and 17) Perceived Barriers (SYRAAP), 18) likelihood of involvement in peer recovery support group meetings and 19) expectation of helpfulness to current treatment and recovery (TSEE). Because data were collected via multiple measures across multiple time points, there was some variability in the n’s.

Due to the large number of predictor variables considered, preliminary analyses were conducted to obtain zero-order rank correlations of each predictor with each outcome across time. Only variables that demonstrated statistically significant relations were retained for the final analyses. With each outcome, the treatment effect was assessed and included in the model only if it was a significant predictor. Statistical results were obtained with the SAS (2010) program, and the Poisson regression model, standard negative binomial and zero-inflated negative binomial regression models were estimated with the NLMIXED procedure.

To determine whether stimulant drug of choice predicted the type of 12-step meeting attended (AA, NA, CA, or CMA), a zero-inflated Poisson regression model was used. Analyses were conducted on attendance at AA and NA meetings, but revealed a notable lack of attendance at CA and CMA meetings for both stimulant groups. This low attendance prevented any further statistical group comparisons for CA and CMA attendance.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Of the 471 participants randomized to Stage 12 or TAU, 50 (TAU, n=20, Stage-12, n=30) did not have post-baseline data so were not included in subsequent analyses (see Donovan et al., 2013 for more detail). This left an analysis sample of N=421. The overall study sample was predominantly female (59%) and non-Hispanic Caucasian (49%). Those randomized to STAGE-12 compared to TAU did not differ on demographic, prior 12-step involvement, expectancies, or readiness to engage in 12-step. Detailed demographic and baseline characteristics are reported elsewhere (Donovan et al., 2013). For the current analyses, baseline demographic characteristics were compared for cocaine versus methamphetamine users. Results showed that compared to Methamphetamine users, Cocaine users were significantly less likely to be Caucasian (46.91% vs 53.09%, χ2 = 54.99, p<.001) or court-mandated (43.68% vs 56.32%, χ2 = 22.69, p<.001), and significantly more likely to be older (Mcocaine = 40.74 vs Mmeth = 34.85, t418 = 6.11, p<.001) and to have a Baseline ASI Alcohol Composite score of greater than zero (73.95% vs 26.05%, χ2 = 20.73, p<.001). Cocaine and Methamphetamine users did not differ on gender (χ2 = 3.31, p = .069), marital status (χ2 = 1.85, p = .869), ASI Drug Composite score greater than zero (χ2 = 1.27, p = .260), or education (t406 = 0.70, p = .481).

3.2 Use of 12-step Programs (Q1)

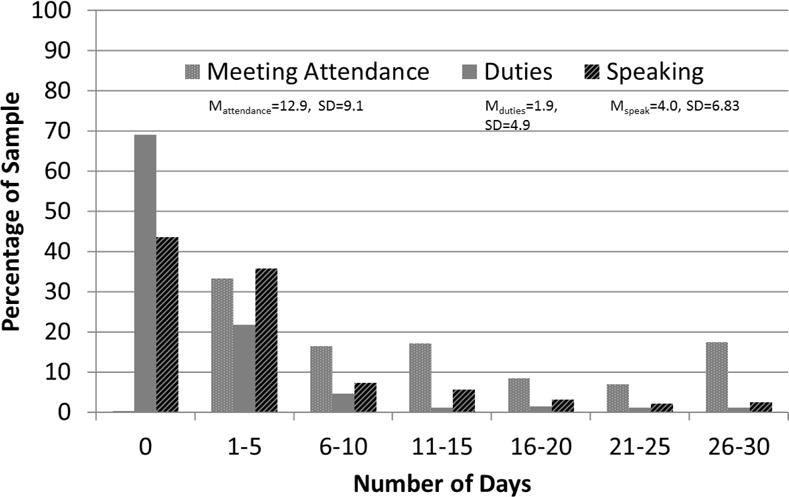

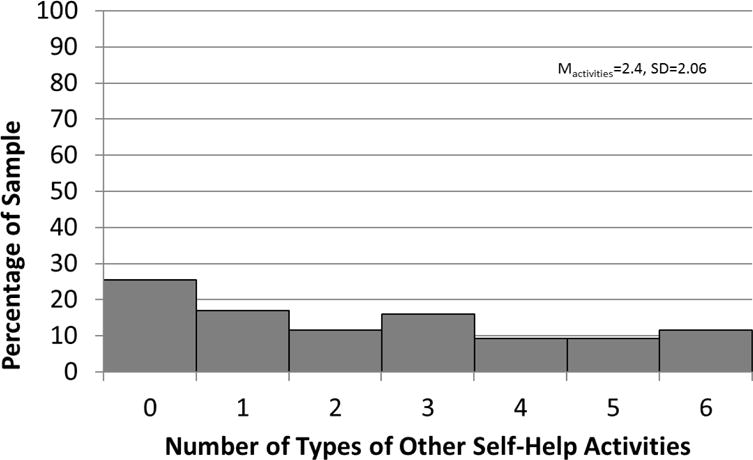

Responses to the SHAQ revealed that nearly all participants (99.7%) attended 12-step meetings in the 30 days prior to study enrollment (M = 12.9 days, SD = 10.0). The majority (69%) reported they had not taken on Duties at meetings, and overall averaged approximately two days of Duties (M = 1.9 days, SD = 4.9). Forty-three percent reported they had not Spoken at meetings while 36% reported Speaking on one to five days out of the past 30 (overall M = 4.0 days, SD = 6.8). Twenty-five percent reported having engaged in no other 12-step related Activities, while the rest (74.59%) reported engaging in one to six types of other Activities (overall M = 2.4, SD = 2.1). See Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Baseline number of days in the past 30 of meeting attendance, duties and speaking.

Figure 2.

Baseline past 30 day other self help activities

3.3 Baseline Variables Predicting 12-Step Participation and Attendance in Stimulant Users (Q2 and Q3)

Preliminary analyses indicated only five of nineteen baseline variables were related to the outcome variables in stimulant users: 1) the pre-randomization 3-month average number of days of peer recovery support meeting attendance captured from the SUC; 2) the baseline number of other types of Self-Help Activities in the last 30 days from the SHAQ; and 3) the three SYRAAP subscales, (3) Perceived Benefit, (4) Perceived Severity, and (5) Perceived Barriers. These five were examined as predictors of the two outcome variables, post-intervention 12-step participation and attendance. The predictor variables were interpreted using odds ratios (ORs) and rate ratios (RRs). Given that a unit of measurement of one day or one subscale score does not provide as useful information as does a larger unit of increase, ORs and RRs are provided in terms of a one standard deviation increase in the variable. The same standard deviation value related to each variable was used across all time points to allow proper comparison across assessments. The mean, range and standard deviation of each of the predictors are as follows: average pre-randomization attendance (M = 5.26, range 0 – 30 days, SD = 6.52), number of other types of Self-Help Activities (M = 2.35, range 0– 6 types, SD = 2.05), Perceived Benefit (M = 21.68, SD = 3.86), Perceived Severity (M = 22.56, SD = 3.49) and Perceived Barriers (M = 9.46, SD = 3.96). The range for each SYRAAP subscale score is 5 to 25.

3.3.1 Days in the last 30 of AA, NA, CA, or CMA meeting Attendance

The average number of days of pre-randomization meeting attendance, other types of Self-Help Activities in the last 30 days, and the Perceived Benefit score significantly predicted baseline meeting Attendance (Table 2). For every 6 ½ day standard deviation increase in average pre-randomization attendance, the number of days of Attendance increased at a rate of 54% (RR = 1.54) at baseline, with all other variables in the model held constant. Similarly, for nearly every four standard deviation increase in the score on the Perceived Benefit subscale, the number of days of Attendance increased by a rate of 26% (RR = 1.26). For every two-activity increase in the number of other types of Self-Help Activities, the number of days of Attendance at baseline increased by a rate of 20% (RR = 1.20).

Table 2.

Results of Regression Models for 2 Outcomes: Number of Days Attending AA, NA, CA or CMA and Number of Other Types of Self-help Activities Attended

| Predictors | Maximum Number of Days Attending AA, NA, CA or CMA Meetings in the Last 30 Days | Number of Other Types of Self-help Activities Attended in the Last 30 Days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p-value | RR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| (n=286) | Baseline | (n = 370) | ||||

| Average Attendance | 1.54 | 1.41, 1.68 | <.001 | 1.33 | 1.26, 1.40 | <.001 |

| Perceived Benefit | 1.26 | 1.12, 1.42 | <.001 | 1.22 | 1.11, 1.35 | <.001 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.98 | 0.88, 1.10 | 0.789 | 1.16 | 1.06, 1.28 | 0.002 |

| Perceived Barriers | 1.05 | 0.96, 1.16 | 0.264 | 0.92 | 0.85, 1.00 | 0.053 |

| No. of Other Activities | 1.20 | 1.10, 1.32 | <.001 | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||

| (n = 251) | End-of-Treatment | (n = 297) | ||||

| Treatment | – | – | – | 1.25 | 1.10, 1.42 | 0.001 |

| Average Attendance | 1.21 | 1.09, 1.35 | 0.001 | 1.10 | 1.04, 1.16 | 0.001 |

| Perceived Benefit | 1.12 | 0.98, 1.28 | 0.107 | 1.12 | 1.02,1.22 | 0.013 |

| Perceived Severity | 1.12 | 0.98, 1.26 | 0.087 | 1.14 | 1.04, 1.24 | 0.004 |

| Perceived Barriers | 1.03 | 0.92, 1.15 | 0.653 | 0.91 | 0.84, 0.98 | 0.017 |

| No. of Other Activities | 1.13 | 1.01, 1.27 | 0.033 | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||

| (n = 211) | 3-Month Follow-up | (n = 280) | ||||

| Treatment | – | – | – | 1.33 | 1.17, 1.52 | <.001 |

| Average Attendance | 1.21 | 1.11, 1.33 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.07, 1.20 | <.001 |

| Perceived Benefit | 1.16 | 1.03, 1.31 | 0.016 | 1.09 | 1.00, 1.20 | 0.047 |

| Perceived Severity | 1.10 | 0.98, 1.21 | 0.117 | 1.10 | 1.01, 1.20 | 0.028 |

| Perceived Barriers | 1.04 | 0.93, 1.15 | 0.504 | 0.92 | 0.85, 1.00 | 0.040 |

| No. of Other Activities | 1.08 | 0.98, 1.20 | 0.113 | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||

| (n = 178) | 6-Month Follow-up | (n = 271) | ||||

| Treatment | – | – | – | 1.28 | 1.11, 1.47 | <.001 |

| Average Attendance | 1.12 | 0.98, 1.27 | 0.091 | 1.15 | 1.08, 1.23 | <.001 |

| Perceived Benefit | 1.18 | 1.01, 1.37 | 0.039 | 1.04 | 0.96, 1.14 | 0.345 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.98 | 0.86, 1.12 | 0.736 | 1.04 | 0.95, 1.13 | 0.423 |

| Perceived Barriers | 1.05 | 0.90, 1.21 | 0.540 | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.05 | 0.495 |

| No. of Other Activities | 1.11 | 0.97, 1.27 | 0.120 | – | – | – |

Note: A negative binomial regression was used for the maximum number of days attending meetings in the last 30 days; and a Poisson regression was used for number of other types of self-help activities attended in the last 30 days. P values of < .05 for predictors of future time points are highlighted. Rate Ratios (RR) represent a count of non-zero attendance and self-help activities, interpreted as incidence rates. Example: at End-of-Treatment, the rate of the number of days of attendance increases by 21% (RR=1.21) for every standard deviation (SD = 6.52) increase in average attendance at Baseline.

At end-of-treatment, average pre-randomization attendance and number of types of other Self-Help Activities predicted past 30-day meeting Attendance. At 3-month follow-up, average pre-randomization attendance and Perceived Benefit predicted meeting Attendance, and at 6-month follow-up, only Perceived Benefit predicted meeting Attendance. Overall, a pattern emerged, where average pre-randomization 12-step attendance predicted the days of attendance at all time points (end-of-treatment, 3- and 6-month follow-up). Pre-randomization Perceived Benefit of 12-step also predicted Attendance at 3- and 6-month follow-up but not at end-of-treatment. At this time point, number of other Self-Help Activities was instead a significant predictor of attendance.

3.3.2 Number of other types of Self-Help Activities attended in the past 30 days

There was a significant treatment effect, with those in Stage-12 indicating a slightly higher rate of the number of types of other Self-Help Activities at each time point (RR = 1.25, 1.33 and 1.28, respectively for end-of-treatment, 3-month and 6-month follow-up; Table 2). Controlling for this treatment effect, average pre-randomization meeting attendance significantly predicted number of other Self-Help Activities across all time points. Pre-randomization Perceived Benefit significantly predicted Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up, but not 6-month follow-up. A similar pattern over time emerged for pre-randomization Perceived Severity and Perceived Barriers: Perceived Severity at baseline was related to increased number of Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up, and Perceived Barriers at baseline was significantly related to decreases in number of Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up. For both Perceived Severity and Perceived Barriers, the predictor effect fell away by the 6-month follow-up.

3.3.3 Days in the last 30 of Speaking at AA, NA, CA, or CMA meetings

With this outcome, only average pre-randomization attendance and number of other types of Self-Help Activities were significant predictors at mid-treatment, but they did not contribute to the prediction of “never” Speaking (zero-inflated portion). For every standard deviation increase in average pre-randomization attendance (about 6 ½ days), the rate of the number of days Speaking at mid-treatment increased at a rate of 21% (RR = 1.21). For the number of types of other Self-Help Activities, with a standard deviation increase (about 2 activity types), the number of days of Speaking increased by a rate of 32% (RR = 1.32). There are no other statistically significant effects after this time point.

3.3.4 Days in the last 30 of Duties at AA, NA, CA, or CMA meetings

Table 3 shows that the pre-randomization number of types of other Self-Help Activities is a significant predictor at each time point for the zero-inflation part of the model. In other words, individuals who indicated more types of other Self-Help Activities at baseline were more likely to perform Duties (i.e., had lower odds of “never” performing Duties) at an AA, NA, CA or CMA meeting at end-of-treatment (OR = 0.22), 3-month (OR = 0.63) and 6-month follow-ups (OR = 0.62).

Table 3.

Regression Results for Number of Days of Self-reported Duties at AA, NA, CA or CMA Meetings in the Last 30 Days

| Zero-inflation (Never Performing Duties) | Count or Rate of Duties Performed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | RR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Baseline (n = 285) | ||||||

| Average Attendance | 0.42 | 0.21, 0.82 | 0.013 | 1.40 | 1.05, 1.87 | 0.023 |

| Perceived Benefit | 0.81 | 0.38, 1.74 | 0.585 | 1.47 | 0.93, 2.33 | 0.099 |

| Perceived Severity | 1.03 | 0.48, 2.19 | 0.948 | 1.11 | 0.67, 1.83 | 0.680 |

| Perceived Barriers | 0.65 | 0.34, 1.23 | 0.187 | 0.79 | 0.58, 1.08 | 0.144 |

| No. of Other Activities | 0.42 | 0.23, 0.76 | 0.004 | 1.15 | 0.82, 1.60 | 0.424 |

|

| ||||||

| End-of-Treatment (n = 241) | ||||||

| Average Attendance | 1.86 | 0.82, 4.22 | 0.141 | 1.28 | 0.98, 1.67 | 0.075 |

| Perceived Benefit | 0.54 | 0.16, 1.81 | 0.317 | 0.81 | 0.57, 1.15 | 0.232 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.60 | 0.24, 1.53 | 0.287 | 1.31 | 0.87, 2.02 | 0.196 |

| Perceived Barriers | 0.26 | 0.46, 1.51 | 0.135 | 0.65 | 0.48, 0.86 | 0.004 |

| No. of Other Activities | 0.22 | 0.06, 0.80 | 0.022 | 1.14 | 0.83, 1.57 | 0.426 |

|

| ||||||

| 3-Month Follow-up (n = 205) | ||||||

| Average Attendance | 0.58 | 0.37, 0.91 | 0.020 | 0.99 | 0.81, 1.21 | 0.919 |

| Perceived Benefit | 1.15 | 0.71, 1.84 | 0.571 | 0.88 | 0.68, 1.15 | 0.352 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.73 | 0.46, 1.16 | 0.188 | 1.25 | 0.92, 1.69 | 0.163 |

| Perceived Barriers | 1.08 | 0.71, 1.65 | 0.717 | 0.85 | 0.66, 1.09 | 0.202 |

| No. of Other Activities | 0.63 | 0.40, 0.97 | 0.037 | 1.27 | 1.00, 1.61 | 0.052 |

|

| ||||||

| 6-Months Follow-up (n =171) | ||||||

| Average Attendance | 1.07 | 0.71, 1.62 | 0.737 | 1.11 | 0.83, 1.48 | 0.493 |

| Perceived Benefit | 0.99 | 0.60, 1.62 | 0.957 | 0.95 | 0.70, 1.29 | 0.747 |

| Perceived Severity | 1.04 | 0.60, 1.81 | 0.878 | 1.39 | 1.00, 1.92 | 0.053 |

| Perceived Barriers | 0.92 | 0.55, 1.53 | 0.737 | 0.77 | 0.57, 1.05 | 0.101 |

| No. of Other Activities | 0.62 | 0.39, 0.99 | 0.047 | 1.09 | 0.81, 1.46 | 0.592 |

Note: A zero-inflated negative binomial model was utilized with the logistic portion (never performing duties) and the negative binomial (or count) portion interpreted separately in terms of odds ratios and incidence rate ratios, respectively. Example: the number of types of other Self-Help Activities is a significant predictor at each time point, indicating that individuals with more types of other Self-Help Activities at baseline were more likely to perform Duties (e.g., had lower odds of “never” performing Duties). For those who did perform Duties (the count part of the model), the Perceived Barriers variable is statistically significant at end-of-treatment (p = .0036). That is, for every standard deviation increase in the score on Perceived Barriers at baseline, the rate of the number of days of Duties decreased by 35% (OR = 0.65).

Table 3 also shows that for those who did perform Duties (the count part of the model), only the Perceived Barriers variable was statistically significant at end-of-treatment (p = .004). For every standard deviation increase in the score on Perceived Barriers (SD = 3.96) at baseline, the rate of the number of days of Duties decreased by 35% (OR = 0.65).

3.4 Stimulant Drug of Choice and 12-step Participation and Attendance (Q4)

Participants reported their primary drug (DSM-IV Checklist) as cocaine (65.6%) or amphetamine/methamphetamine (34.5%). Based on the rank-order correlation of stimulant drug of choice with the outcome variables, the results indicated no statistically significant relations of stimulant drug of choice with the number of days of Attending meetings (r = 0.11, p = 0.102), Speaking at meetings (r = −0.03, p = 0.658), Duties at meetings (r = −0.01, p = 0.875), or the number of other types of Self-Help Activities attended (r = −0.03, p = 0.658). Drug of choice was not significantly related to the four outcome variables at any time points.

3.5 Drug of Choice and 12-step Meeting Type

At end-of-treatment, cocaine users were more likely than methamphetamine or amphetamine users to have attended AA meetings (i.e. had lower odds of “not attending”) (OR = 0.57 [95% CI = 0.33, 0.98], X2 = 4.15, p = 0.042). Of the participants who did attend AA, cocaine users attended at a significantly higher rate (RR = 1.16, [95% CI = 1.06, 1.28], X2 = 9.46, p = 0.002), with model based estimates of 12.78 days for cocaine users and 11.0 days for methamphetamine/amphetamine users. For NA meetings, the two groups did not differ in whether or not they attended, but cocaine users attended on significantly more days than did methamphetamine/amphetamine users (RR = 1.42, [95% CI = 1.30, 1.55], X2 = 57.57, p < .001). Model based estimates suggested an average NA attendance of 11.76 days for cocaine and 8.30 days for methamphetamine/amphetamine users.

At the 3-month follow-up, the two groups of stimulant users did not differ in whether or not they attended AA or NA meetings, but they did differ in how many days they attended each type of meeting. Cocaine users attended AA meetings on significantly more days (model based estimate = 11.61 days) than did amphetamine/methamphetamine users (model based estimate = 10.20 days) (RR = 1.14, [95% CI = 1.03, 1.26], X2 = 6.08, p = 0.013). Cocaine users also attended NA meetings on significantly more days (model based estimate = 11.58 days) than did amphetamine/methamphetamine users (model based estimate = 9.43 days) (RR = 1.23, [95% CI = 1.11, 1.35], X2 = 16.54, p <.001).

A similar pattern emerged at the 6-month follow-up, in that neither group was more likely to attend AA or NA groups than the other. However, of those who did attend, Cocaine users attended AA on significantly more days (model based estimate = 10.90 days) (RR = 1.18, [95% CI = 1.05, 1.33], X2 = 7.52, p = 0.006), and NA on significantly more days (model based estimate = 10.74 days) (RR = 1.42, [95% CI = 1.25, 1.61], X2 = 29.36, p <.001), than did amphetamine/methamphetamine users (model based estimates = 9.24 days for AA, and 7.56 days for NA).

Separate from the analyses above, Table 4 shows the percent of attenders who were primary cocaine or amphetamine/methamphetamine users attending each type of meeting, at each time point (end-of-treatment, 3-month and 6-month follow-up). Although, as reported above, cocaine and amphetamine/methamphetamine users had similar odds of whether or not they attended AA and NA, users in both stimulant groups reported slightly higher attendance at NA over AA at nearly all time points.

Table 4.

Percent of cocaine and amphetamine/methamphetamine users attending 12-step groups in the past 30 days

| Stimulant Group | AA % (out of total n) |

NA % (out of total n) |

CA % (out of total n) |

CMA % (out of total n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-of-Treatment | ||||

| Cocaine Users | 72.84 (162) | 79.76 (168) | 18.47 (157) | 0.64 (156) |

| Amphetamine/Methamphetamine Users | 60.23 (88) | 89.13 (92) | 2.27 (88) | 2.25 (89) |

|

| ||||

| 3-Month Follow-Up | ||||

| Cocaine Users | 70.83 (144) | 78.47 (144) | 12.59 (143) | 2.13 (141) |

| Amphetamine/Methamphetamine Users | 67.11 (76) | 77.92 (77) | 4.05 (74) | 1.35 (74) |

|

| ||||

| 6-Month Follow-Up | ||||

| Cocaine Users | 68.75 (112) | 73.39 (109) | 12.62 (103) | 0.00 (106) |

| Amphetamine/Methamphetamine Users | 70.31 (64) | 67.69 (65) | 1.56 (64) | 1.56 (64) |

Bold = highest rate of attendance.

3.6 Same-time Assessments of Attendance and Activities with Stimulant Use

Because attendance and participation in 12-Step meetings is only important insofar as it reduces stimulant use, we examined the relationship between attendance and participation outcomes and stimulant use outcome. Both maximum number of days of Attendance (OR = 1.08, p = .0003) and the number of types of Self-Help Activities (OR = 1.25, p = .0045) predicted both abstinence and use of stimulants at baseline (see Table 5). The rate of stimulant use was negatively related to both Attendance and the number of Self-Help Activities, with RR = 0.98 (p = .031) and RR = 0.92 (p = .030), respectively. At end-of-treatment, only Attendance predicted abstinence (OR = 1.10, [95% CI = 1.04, 1.17, p = .001). At the 3-month follow-up, both Attendance and number of Self-Help Activities predicted abstinence. At the 6-month follow-up, only the number of Self-Help Activities predicted abstinence (OR = 1.51, [95% CI = 1.21, 1.75], p < .001). Neither variable predicted the rate of stimulant use after mid-treatment.

Table 5.

ORs (abstinence) and incidence RRs (days of use) of Same-Time Assessments of the Maximum Number of Days Attending AA, NA, CA or CMA Meetings in the Last 30 Days and the Baseline Number of Other Types of Self-help Activities Attended in the Last 30 Days with the Primary Outcome of Stimulant Substance Use within a 30-day Window of Assessment.

| n | Zero-inflation (Abstinence vs. Non-abstinence) | Count Days of Use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | RR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Baseline* | |||||||

| Maximum Days Attendance | 336 | 1.08 | 1.04, 1.13 | <.001 | 0.98 | 0.96, 0.99 | 0.031 |

| Number of Self-Help Types | 441 | 1.25 | 1.07, 1.45 | 0.005 | 0.92 | 0.86, 0.99 | 0.030 |

|

| |||||||

| End-of-Treatment | |||||||

| Maximum Days Attendance | 308 | 1.10 | 1.04, 1.17 | 0.006 | 0.98 | 0.94, 1.03 | 0.509 |

| Number of Self-Help Types | 349 | 1.60 | 0.88, 2.88 | 0.118 | 0.87 | 0.73, 1.03 | 0.105 |

|

| |||||||

| 3-Month Follow-up | |||||||

| Maximum Days Attendance | 260 | 1.09 | 1.01, 1.18 | 0.023 | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 0.899 |

| Number of Self-Help Types | 327 | 1.67 | 1.24, 2.25 | 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.86, 1.14 | 0.898 |

|

| |||||||

| 6-Months Follow-up | |||||||

| Maximum Days Attendance | 170 | 1.05 | 0.99, 1.11 | 0.079 | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.01 | 0.088 |

| Number of Self-Help Types | 318 | 1.51 | 1.31, 1.75 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 0.90, 1.15 | 0.802 |

Maximum Days Attendance = Maximum Number of Days Attending AA, NA, CA or CMA Meetings in the Last 30 Days

Number of Self-Help Types = Number of Other Types of Self-help Activities Attended in the Last 30 Days

Note: The treatment effect is not included at baseline.

4. Discussion

4.1 Results Summary

Nearly all patients with stimulant dependence entering a trial of a 12-Step Facilitation intervention had been attending 12-step meetings in the 30 days prior to randomization, although they varied in their frequency of attendance. These early treatment seekers were more likely simply to attend, rather than actively participate in, meetings and activities. The high rate of pre-randomization 12-step attendance may have been at least partially due to the particular treatment programs participating in this study. Programs that were interested, and ultimately selected, all endorsed in some way a 12-step philosophy of treatment. This might have attracted patients with a similar background or preference. In addition, for individuals contemplating entering treatment who have had prior 12-Step experience, attending meetings may have been seen as an initial step in moving from thinking about treatment to engaging with it.

Preliminary analyses examined several individual characteristics that might predict 12-step attendance and participation during and after treatment, based on prior alcohol-related studies. The present study found that demographic characteristics, including age, race and gender were unrelated to 12-step attendance and involvement, as were prior treatment history and psychiatric, alcohol, and drug problem severity. In addition, whether participants’ primary drug was methamphetamine or cocaine was unrelated to the four 12-step outcome variables representing attendance and participation in 12-step meetings. Drug of choice was, however, associated with some baseline demographic differences (e.g. ethnicity, legal status, ASI Alcohol composite score, age) and with differential days of AA and NA attendance among those who reported any attendance. Cocaine users reported more days of attending AA or NA at all three post-treatment assessments.

The primary finding of this study is one of continuity: both readiness to engage in 12-step content, as measured by the SYRAAP Benefits and Barriers scales, and specific prior attendance and active participation (defined as speaking, having duties at, or engaging in related activities) with 12-step programs, were the main signs pointing to future involvement in these same areas. The fact that these 12-step-specific variables were predictive is consistent with findings reported by Zemore and Kaskutas (2009). Their test of the Theory of Planned Behavior with SUD treatment patients showed that attitudes, norms, intentions and perceived control regarding attendance at 12-step meetings longitudinally predicted 12-step involvement, which, in turn, was related to sobriety.

In the current study, specifically, Perceived Benefit of AA predicted 12-step Attendance at baseline, 3-month and 6-month follow-up. In previous studies, Perceived Benefit has been shown to predict 12-step attendance and participation in patients with alcohol and drug use disorders but not specifically in patients with stimulant use disorders (Kingree et al., 2007). The present findings suggest that the connection between Perceived Benefit and Attendance holds true for stimulant users as well. The only time point in which baseline Perceived Benefit did not predict 12-step Attendance was at end-of-treatment. Instead, at this time point, number of other Self-Help Activities (e.g., calling a sponsor, reading literature) was significant. A possible explanation is that treatment’s emphasis on the benefits of 12-step activities and assertive encouragement to engage in them may have been especially fresh for participants just completing 8 weeks of 12-step facilitation as part of IOP, such that those who entered the study with greater perceived benefit were more likely to be engaging in other activities approximately 8 weeks later.

The current study also showed that the number of other types of Self-Help Activities was significantly predicted by pre-randomization measures of 12-step attendance, and Perceived Benefit, Severity, and Barriers. Patients who had greater average 12-step attendance in the 90 days prior to study enrollment had a significantly greater number of Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment, 3-month and 6-month follow-ups. Those who endorsed greater Perceived Benefit to 12-step, and greater Perceived Severity of their problems, prior to study enrollment had significantly more Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Those who saw more barriers to 12-step prior to study enrollment, saw a decrease in their number of Self-Help Activities at end-of-treatment and 3-month follow-up. These significant predictor relationships disappeared somewhere between the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups, in that by 6-months, only pre-randomization average 12-step attendance continued to be significantly related to Self-Help Activities. The finding that pre-randomization 12-step attendance is the best predictor of later engagement in Self-Help Activities such as calling a sponsor and reading 12-step literature is consistent with other studies showing that pre-treatment peer-recovery support group attendance predicts post-treatment participation (Manning et al., 2012; Vederhus et al., 2015).

This study also showed that performing Duties at all time points (end-of-treatment, 3-month and 6-month follow-up) was predicted by the number of other Self-Help Activities (e.g. calling a sponsor, reading literature) at baseline. The one exception to this was that those who perceived more barriers to 12-step participation at baseline participated in fewer duties at meetings at end-of-treatment. These results again suggest that 12-step engagement predicts continued 12-step engagement, and confirm past findings (Kaskutas, Bond, Avalos, & Ammon, 2009; Manning et al. 2012; Vederhus et al. 2015; Weiss et al. 2000b).

Continuity of attendance and participation takes on greater importance if these outcomes are also related to the primary desired outcome of SUD treatment, increased abstinence or fewer days of substance use among those not abstinent. Although not one of the main questions planned for this paper, analyses did address the same-time-point relationship between measures of 12-Step attendance and participation and participants’ stimulant drug use. Controlling for STAGE-12 versus TAU assignment, attendance and number of types of 12-Step activities predicted abstinence at a number of time points. This, together with findings from the study’s primary outcome paper (Donovan et al., 2013) showing that STAGE-12 participants evidenced greater 12-Step attendance and participation and were more likely to be abstinent than those in TAU, underscores the importance of such attendance and participation and of interventions that increase attendance and participation.

Given that Donovan et al. (2013) reported differences between STAGE-12 and TAU conditions in three of the attendance and participation outcomes (Attendance, number of Self-Help Activities, and Duties), it may seem unusual that treatment assignment was included only in the model predicting number of other types of activities. The lack of prediction of 12-Step outcomes by treatment group in these analyses is not considered contrary to prior findings in that these analyses were different, examining the relationships between predictors and outcomes within time points instead of longitudinally across time.

There is little information about 12-step attendance and participation among methamphetamine users (Donovan & Wells, 2007). The finding that neither cocaine nor methamphetamine users reported much attendance at CA and CMA meetings is consistent with the small amount of available information (Weiss et al., 2000a). This may be because these specialized meetings are less available (Donovan & Wells, 2007), or too triggering for cocaine users (Weiss et al., 2000a). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether choice of primary stimulant drug predicts 12-step involvement.

Although the two stimulant user groups were equally likely to attend or not attend AA and NA, cocaine users attended on significantly more days. And, out of the four types of meetings, NA was the most popular for both stimulant groups. The importance of these findings is unclear, as other factors, such as treatment site, are confounded with primary stimulant drug. In addition, given that at baseline cocaine users were more likely to report problems with alcohol and be court-mandated to treatment, we cannot determine whether cocaine users attended more meetings because they had more alcohol-related concerns, or because they were legally mandated to attend meetings. However, findings from a recent study suggest that the attendance of one type of 12-step group over the other (e.g., AA vs NA) may be irrelevant in terms of positive outcomes. Kelly and colleagues (2014) found that drug-dependent individuals whose primary drug was not alcohol and who attended AA did not differ in their 12-step participation and abstinence rates compared to those who attended NA meetings.

4.2 Implications for Treatment

Those receiving TSF plus TAU, compared to those receiving TAU alone, reported significantly more participation in other 12-step activities throughout treatment and at follow-ups. Those receiving the TSF intervention in this study were more likely to be abstinent by the end of treatment and at follow-up (Donovan et al., 2013). Although 12-Step attendance has been associated with greater rates of abstinence from both alcohol and other illicit drugs, including stimulants, participation in 12-step activities may be a better predictor of abstinence than attendance. This is consistent with prior findings (Weiss et al., 2005). It is not uncommon that patients enrolled in SUD treatment attend meetings without being familiar with 12-step recovery support and, subsequently, they may be less likely to follow through with attendance and participation after treatment. Those who have a better understanding may become more engaged and participate in 12-step activities outside of the meetings. Specific TSF programming and/or treatment programs that more generally promote 12-step groups as part of recovery might consider ways to increase the perceived benefits and decrease the perceived barriers to engaging in 12-step peer recovery support groups. Introducing and preparing patients on how to best use 12-step meetings in their recovery, compared to simply urging attendance alone, may lead to more positive changes in beliefs and attitudes.

4.3 Implications for Future Research

There may be little value in continuing to explore demographic characteristics as predictors of 12-Step involvement, as such investigations yield inconsistent results and contribute little to identifying patients with a low likelihood of participation or avenues for improving participation. Based on the findings presented here, measures of perceptions and behaviors that are 12-step specific should instead be the focus of research that seeks to predict 12-step involvement. Shining the spotlight on those with low initial belief or involvement should help to identify why these individuals are non-attenders, and whether their expectations regarding the benefits of 12-step programs may need to be re-calibrated or they should be directed to alternate sources of support during and post-treatment. There also may be some individuals who need little in the way of 12-Step facilitation, and who will continue to use 12-step because it is familiar, beneficial, and they have already been engaged prior to their admission to IOP.

Little research exists regarding the utility of 12-step programs for methamphetamine users. The current study suggests that they may differ from cocaine users in their frequency of 12-step attendance, but primary substance is confounded with treatment site in the current study. These are areas for further research.

4.4 Limitations

This study included only individuals initiating treatment in CTN community treatment programs (CTPs). These programs may represent a select set in that they are interested in research involvement and may be more ready than other programs to implement treatment innovations. However, to increase the generalizability of findings to typical SUD treatment, the selection process for the STAGE-12 study involved purposefully recruiting three research-naïve sites from among the many programs with membership in the CTN (Potter et al., 2011). A second limitation is that this study only included patients who volunteered to participate in a randomized study of TAU+STAGE-12 versus TAU. Such patients may be more interested in involvement in 12-step programs or may be generally more highly motivated. Notably, both limitations apply to most treatment studies; in fact, the CTPs made significant efforts to recruit all potentially eligible patients, as evidenced by the 62% female sample which is atypical for SUD treatment. Additional limitations include, 1) because availability of AA/NA/CA/CMA meetings may have varied between study sites, our analyses of 12-step group attendance in cocaine and methamphetamine users may be viewed as descriptive and a way to illustrate where participants are going based on what is available within their communities; 2) the reduced sample sizes at the follow-up assessment points are due to the regression analyses requiring that all predictors (average attendance, perceived benefit/severity/barriers and other activities) have available data, which further required that all item-level data be available for each subscale, combined with natural study attrition and typical missing data; 3) we acknowledge the possibility for inflated Type I error due to the number of tests done.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported by a series of grants from NIDA as part of the Cooperative Agreement on National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN): Appalachian/Tri-States Node (U10DA20036), Florida Node Alliance (U10DA13720), Ohio Valley Node (U10DA13732), Oregon Node (U10DA13036), Pacific Region Node (U10DA13045), Pacific Northwest Node (U10DA13714), Southern Consortium Node (U10DA13727), and Texas Node (U10DA20024). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA.

We would like to express our appreciation to the patients and the administrative, clinical, and research staff of the 10 community-based treatment programs that participated in the present study: Center for Psychiatric & Chemical Dependency Services, Pittsburgh, PA; ChangePoint, Inc. Portland, OR; Dorchester Alcohol & Drug Commission, Summerville, SC; Evergreen Manor, Everett, WA; Gateway Community Services, Jacksonville, FL; Hina Mauka, Kaneohe, HI; Maryhaven, Columbus, OH; Nexus Recovery Center, Dallas, TX; Recovery Centers of King County, Seattle, WA; Willamette Family Treatment Services, Eugene, OR.

References

- Brown BS, O’Grady KE, Farrell EV, Flechner IS, Nurco DN. Factors associated with frequency of 12-step attendance by drug abuse clients. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:147–160. doi: 10.1081/ada-100103124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Seraganian P, Tremblay J, Annis H. Process and outcome changes with relapse prevention versus 12-step aftercare programs for substance abusers. Addiction. 2002;97:677–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell PE, Cutter HSG. Alcoholics anonymous affiliation during early recovery. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Rounsaville BJ. Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction. 1998;93:713–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Frankforter TL, Rounsaville BJ. One-year follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol users: Sustained effects of treatment. Addiction. 2000;95:1335–1349. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95913355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Shi JM, Eagan D, Ball SA. Efficacy of disulfiram and Twelve Step Facilitation in cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;126:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Baker S, Donovan DM, Hodgkins CG, Perl HA. Combined group and individual 12-Step facilitative intervention targeting stimulant abuse in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network: STAGE-12. Journal of Groups in Addiction Recovery. 2011;6:228–244. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2011.597196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Daley DC, Brigham GS, Hodgkins CC, Perl HI, Garrett SB, Zammarelli L. Stimulant abusers to engage in 12-step (STAGE-12): A multisite trial in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Wells EA. ‘Tweaking the 12-Step’: The potential role of 12-Step self-help group involvement in methamphetamine recovery. Addiction. 2007;102:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrick CD. Alcoholics Anonymous: Affiliation process and effectiveness as treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1987;11:416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R. After drug treatment: Are 12-step programs effective in maintaining abstinence? American Journal on Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:93–116. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R, Hillhouse MP. Drug treatment and 12-step program participation: The additive effects of integrated recovery activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Stewart D, Marsden J. Attendance at Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, frequency of attendance and substance use outcomes after residential treatment for drug dependence: A 5-year follow-up study. Addiction. 2007;103:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak JJ, Helzer JE, Wetzel MW, Kessel KB, McGee B, Janca A, Przybeck T. The use of the DSM-III-R Checklist for initial diagnostic assessment. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1993;34:375–383. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas L, Bond A, Avalos J, Ammon L. 7-Year trajectories of Alcoholics Anonymous attendance and associations with treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(12):1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG. Do drug-dependent patients attending Alcoholics Anonymous rather than Narcotics Anonymous do as well? A prospective, lagged matching analysis. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49:645–653. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL, Pagano M. Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: A multiple mediator analysis. Addiction. 2012;107:289–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Stout RL, Magill M, Tonigan JS, Pagano ME. Mechanisms of behavior change in alcoholics anonymous: Does Alcoholics Anonymous lead to better alcohol use outcomes by reducing depression symptoms? Addiction. 2010;105:626–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Simpson A, Thompson M, McCrady B, Tonigan JS, Lautenschlager G. The development and initial evaluation of the survey of readiness for alcoholics anonymous participation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:453–462. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Simpson A, Thompson M, McCrady BS, Tonigan JS. The predictive validity of the Survey of Readiness for Alcoholics Anonymous participation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:141–148. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning V, Best D, Faulkner N, Titherington E, Morinan A, Keaney F, Gossop M, Strang J. Does active referral by a doctor or 12-step peer improve 12-step meeting attendance? Results from a pilot randomised control trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;126:131–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, O’Brien CP. Predictors of participation in aftercare sessions and self-help groups following completion of intensive outpatient treatment for substance abuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:152–162. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in Alcoholics Anonymous on individuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obert JL, McCann MJ, Marinelli-Casey P, Weiner A, Minsky S, Brethen P, Rawson R. The matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: History and description. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:157–164. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JS, Donovan DM, Weiss RD, Gardin J, Lindblad R, Wakim P, Dodd D. Site selection in community-based clinical trials for substance use disorders: Strategies for effective site selection. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:400–407. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, Dickow A, Frazier Y, Gallagher C, Zweben J, Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2004;99:708–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld RS, Moore B, Pantalon MV. Contingency management with community reinforcement approach or twelve-step facilitation drug counseling for cocaine dependent pregnant women or women with young children. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Billow R, Debenedetti A. Determinants of 12-step group affiliation and moderators of the affiliation-abstinence relationship. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, DeBenedetti A. A randomized controlled trial of intensive outpatient referral to 12-step self-help groups: One-year outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Beatty GK. Twelve-step program attendance and polysubstance use: Interplay of alcohol and illicit drug use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:864–871. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Toscova R, Miller WR. Meta-analysis of the literature on Alcoholics Anonymous: Sample and study characteristics moderate findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:65–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vederhus JK, Zemore SE, Rise J, Clausen T, Hoie M. Predicting patient post-detoxification engagement in 12-step groups with an extended version of the theory of planned behavior. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2015;10:15. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0036-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Gallop R, Luborsky L, Siqueland L, Frank A, Gastfriend DR. Predictors of self-help group attendance in cocaine dependent patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000b;61:714–719. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Gallop RJ, Najavits LM, Frank A, Crits-Christoph P, Luborsky L. The effect of 12-step self-help group attendance and participation on drug use outcomes among cocaine-dependent patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Gallop R, Onken LS, Gastfriend DR, Daley D, Barber JP. Self-help group attendance and participation among cocaine dependent patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000a;60:169–177.c. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Najavits LM, Hufford C, Kogan J, Thompson HJ. Self-help activities in cocaine dependent patients entering treatment: Results from NIDA collaborative cocaine treatment study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;43:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt J, Kaskutas L. Does diagnosis matter: Differential effects of 12-step participation and social networks on abstinence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:685–707. doi: 10.1081/ada-68486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Kaskutas LA. Development and validation of the Alcoholics Anonymous Intention Measure. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]